It is remotely possible that the EU officialdom will temporarily reverse the train wreck that started last Friday with the resignation of Jurgen Stark from the ECB. That was seen as a sign that Germany has adopted bailout fatigue as official policy. That in turn would mean that Greece will not get any more money lifelines (which as commentators predicted some time ago, means a likely banking crisis, which was the reason for them not to exit the Eurozone).

Mr. Market is giving a big vote of no confidence in European leadership, although the FTSE has reversed some of its early-session losses. The Dax is down 3.1%, the FTSE is off 1.6% (v. 2.2% earlier), and the CAC is down 4.1%. The Euro is at 1.4 (a recovery from when I started on this post) and gold is off about a half a percent (versus a bit over 1% earlier in the day).

But the other big development of last week, the ruling of the German constitutional court on the European Financial Stability Fund, was a major, and likely fatal, blow to the Eurozone. As our Ed Harrison and more recently Wolfgang Munchau of the Financial Times explain, the ruling makes it well nigh impossible for the Eurozone to implement measures that would create a fiscal authority (such as eurobonds) or even allow for an permanent backstop device (the European Stability Mechanism, due to go live in 2013. Note that the ruling did not address the ESM specifically, but the logic of the ruling appears to make a challenge to the ESM a slam dunk). The other way out is for the ECB to step into the breach and “print”, but the Germans have been firmly opposed to that, and Stark’s abrupt exit firmly underscored that point.

If you had any doubts as to the implications of these actions, the Germans appear to harbor no such illusions. Per Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, this is a calculated effort to put Greece to the lash:

First we learn from planted leaks that Germany is activating “Plan B”, telling banks and insurance companies to prepare for 50pc haircuts on Greek debt; then that Germany is “studying” options that include Greece’s return to the drachma.

German finance minister Wolfgang Schauble has chosen to do this at a moment when the global economy is already flirting with double-dip recession, bank shares are crashing, and global credit strains are testing Lehman levels. The recklessness is breath-taking….

Mr Schauble said there would be no more money for Athens under the EU-IMF rescue package until the Greeks “do what they agreed to do” and comply with every demand of `Troika’ inspectors.

Yet to push Greece over the edge risks instant contagion to Portugal, which has higher levels of total debt, and an equally bad current account deficit near 9pc of GDP, and is just as unable to comply with Germany’s austerity dictates in the long run. From there the chain-reaction into EMU’s soft-core would be fast and furious.

Let us be clear, the chief reason why Greece cannot meet its deficit targets is because the EU has imposed the most violent fiscal deflation ever inflicted on a modern developed economy – 16pc of GDP of net tightening in three years – without offsetting monetary stimulus, debt relief, or devaluation.

The Eurozone is addicted to a failing remedy. Even if it could get its integration act in gear, austerity, as we predicted, is only making matters worse. Greece’s finance minister just revised down the 2011 forecast from a 3.8 % contraction to 5.3%. (An interesting anomaly, as Clusterstock points out, is that Greek debt isn’t getting trashed further this morning).

And this is clearly a campaign. Reader Swedish Lex points us to a Reuters story, “ECB’s Stark tells Ireland to ramp up austerity” with the note, “The man must be mad.” Key extracts:

Ireland’s government should cut public sector pay again to get its budget deficit under control, Juergen Stark, the outgoing chief economist at the European Central Bank (ECB), said in an interview published in The Irish Times on Monday.

Speaking hours before his shock resignation on Friday, Stark said Ireland should accelerate efforts to get its budget deficit under control including breaking a pledge to public sector unions to leave wages alone.

“We fully appreciate what the government has already done in correcting public wages,” Stark was quoted as saying.

“(But) there is scope, further room for adjustment, and to be more in line with the wages in the public sector in the euro area as a whole.”

“The government should be even more ambitious in cutting the public deficit ratio, which is still at double-digit level.”

As we’ve pointed out earlier, Ireland is the poster child of “austerity makes debt hangovers even worse.” Its nominal GDP (which is what counts in measuring the impact on ability to pay) has contracted nearly 20%.

And while the German actions puts the future of the Eurozone very much in question, the immediate pressure on Greece comes not just from the news out of Germany but also from countries like the Netherlands that are demanding that Greece post more collateral to support the 109 billion euro facility supposedly agreed to last June.

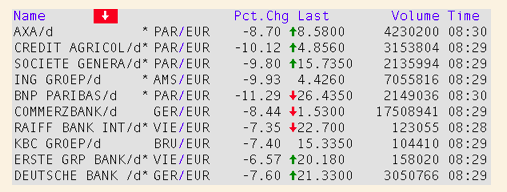

The most important casualties of a Greek default would be French and German banks. One of the reasons for the continued sell off is the fear that Moodys will downgrade French banks. A snapshot on the bloodbath, courtesy FT Alphaville (hat tip Ricard Smith):

In the Great Depression, it was the failure of Credit Anstalt that set off a series of banking failures and debt defaults. In our rerun of sorts, it looks like Jurgen Stark’s rigid adherence to a failed dogma that will set of an even bigger disaster. So much for the idea that economists had learned from financial crises and developed better reflexes. Economics has to an increasing degree become an exercise in promoting ideologies to defend the privileges of the rentier classes. They look to be about to be hoist on their own petard. Unfortunately, a very large number of innocent bystanders will suffer along with them.

Stark is considered to be one of the german chicago boys. and unions are of course anathema.

Yeah.

One could suspect that Greek lending undertaken in the past five or ten years was designed to blow up (how’s those credit-default swaps holding up? Where did the cash to buy those particular insurance policies come from? Or, asked another way, who held such?): and maybe to take the Euro with it (or to give it a good kick in the teeth).

How does a US credit bubble “secured” by excessive residential real-estate valuations become an EU banking problem? Or is this a completely unrelated problem with respect to those economic problems suffered by the US in 2008-2009? Is there any connection at all between the events? If so, what is it; and how is it effected?

If there is some connection, some relation, does its transmission between economic realms pass through Greece? Why? How precisely was the Greek banking system different from other European countries’ banking systems prior to the threatened Greek defaults, so as to make Greece the point of fracture?

In sum: why Greece?

Why Greece?

Weakest link.

were there any Synthetic CDOs that used credit default swaps referencing sovereign debt?

oh wait, the entire market is opaque. Thanks Greenspan, Summers, Levitt, Rubin, Thank you all!

Why Greece?

Because German banks were big buyers of Wall Street junk during the housing bubble and already weakened when the Greek problem emerged. Germany is now the camel’s back and little Greece is the straw.

See Michael Lewis’ article in the latest Vanity Fair.

So Stark is a German Chicago boy….can I nominate Milton Friedman as the Worst Person of the late 20th century? The Chicago School of Economics has created so much misery throughout the world.

Just had a moment of frisson here.

I was trying to find a historical parallel, where a country or countries were forcing another country to repay/reverse a debt, but instead of forcing austerity, the country under the gun went the inflation route instead.

(ok, not exact, but maybe someone learned the wrong lesson long ago.)

Good catch — thus making it doubly ironic that German officials and economists are spouting the line that “we learned the costs of hyper-inflation in the 1920s, and are acting on that lesson”!

Even more frissonable when you consider the fact, read in an economics text no less, that the weimar Hyperinflation was the result of conscious policy decisions by the German Government. “The more things change…”

‘The chief reason why Greece cannot meet its deficit targets is because the EU has imposed the most violent fiscal deflation ever inflicted on a modern developed economy – 16pc of GDP of net tightening in three years – without offsetting monetary stimulus, debt relief, or devaluation.’

Oof — sounds kinda like amputation with no anaesthetic (except maybe a shot of ouzo).

Meanwhile, Greek one-year yields reached a towering 111% this morning.

As they say in the real estate biz, ‘This won’t last!’

But if it did, what rich pickings!

I’m no money-trader…would that 111% be payable in Euros, or some pretend local currency?

The Greek T-note is priced to provide a yield of 111% in euros. But its heavily discounted price assumes that Greece will default and pay back only a fraction of the principal, whether in euros or in drachmas that can be converted to euros.

Whether this yield is a bargain depends on your estimate of the recovery percentage. If Greece pays off 60 cents on the euro, it might be a money-maker. At 30 cents on the euro, you don’t even get all of your principal back.

Who has enough information to engage in such hyper-risky speculation about recovery rates? I sure don’t.

Whether the yield is a “bargain” also depends on how much time elapses before Greece defaults. Bonds typically pay semi-annual coupons. If somehow the Greeks were able to postpone their default for another six months, you would collect a coupon payment equal to 55% of your principal. At that point you would be able to sustain a 45% “haircut” in a default and still break even.

Correction: You would only need to recover 45% (take a 55% “haircut”) in a default scenario to break even.

Right. But who wants to accept this level of risk and uncertainty, just to break even?

Even a 111% yield (which later in the day went to 122%) may not be high enough to compensate buyers.

what if you take all the money the bonds make and use it to buy credit default swaps against a greek default?

sort of like a Magnetar CDO, but using an entire nation’s debt.

What if you could get your bonds linked to the Greek Governments claim on the Elgin Marbles?

It seems obvious at this point that national economies cannot support international currencies. Indeed, even intra-national economies cannot support national currencies. The prime example is the Central Valley of California. The American Currency Union (aka FRN) is clearly not working out for this sector of the nation where unemployment is twenty to thirty percent. As with Greece, Portugal and Ireland, it is time for regions everywhere to be encouraged to adopt their own currency.

Is it even possible to “inflict” deflation?

And how is it that the EU “imposes” on a component member-state , as it is only “imposing” upon itself.

That’s called “self- discipline” in other contexts, and is often held to be a virtue, not a reason to deride.

It seems to me that you are too quick to draw in borders between States and Nations, and even between “economies”.

I think things are more connected, or less separable, in reality. So…be careful that the categories adapted for aiding analysis and understanding are not confused or confounded with that which is itself under examination.

Observation before theory.

Contrary to popular believe. Eurobond will not provide stability. It too will be a subject to wild fluctuation and market manipulation, since the market will be thin and controlled.

The hot money sloshing around is much bigger than the proposed eurobond issuance.

Just look at the US Treasury market. The Eurobond market could not be so deep?

Europe does not want to be a United States of Europe, admit it.

Stark’s proposals are being violently rejected by the Irish Labour Party who are calling him on his BS quite frankly:

http://www.rte.ie/news/2011/0912/economy.html

“And I think arguments that we should further depress the economy because of an inflexible ideological position, is not the way to go.” — Pat Rabbitte, Minister for Communications.

However, will the ruling mean Great Depression 2.0 — with bank failures and the like? I don’t think so. The ECB will step in and ‘print’. There’s no way the German’s would stop them if their banking system looked set to go under. That would be insane.

The Germans are — rather ironically — pushing themselves into a corner and in doing so they’re going to end up seeing the very actions undertaken that they loath the most…

Since IANAE, I can say with some conviction that the 1st Law of Macroeconomics is: “Trying to avoid having to do X is the best way of ensuring you will do X.”

“Irish object to Germans’ reluctance to pay yet more for bailing out countries who partied while Germany economised.” How dare they be so mean?

The trouble is, as usual, the Germans have a point:

Taoiseach’s salary as head of 5mn people $287,900

Bundeskanzler’s salary as head of 82mn people $283,608

(source: http://www.economist.com/node/16525240 )

Is it possible that the German position is being misread?

The German fear of inflation is well-known, but I rarely see an acknowledgment of the German postwar experience in overcoming utter economic chaos and devastation. From Wikipedia:”West Germany proceeded after 1948 to quickly rebuild its capital stock and thus to increase its economic output at stunning rates. The very high capital investment rate thanks to low consumption and a very small need for replacement capital investments (due to the still small capital stock) drove this recovery during the 1950’s.

Contrary to popular belief, the Marshall Plan … was not the main force behind the Wirtschaftswunder.[8][9] Had that been the case, other countries such as the United Kingdom (which received higher economic assistance from the plan than Germany) should have experienced the same phenomenon. … Nonetheless, the amount of monetary aid (which was in the form of loans) received by Germany through the Marshall Plan (about $1.4 billion in total) was far overshadowed by the amount the Germans had to pay back as war reparations and by the charges the Allies made on the Germans for the ongoing cost of occupation (about $2.4 billion per year).[8] In 1953 it was decided that Germany was to repay $1.1 billion of the aid it had received. The last repayment was made in June 1971.[9]”

I am not in a position to know how accurate the above description is, but it seems to me that what is not easily disputed, is the German perception that quality work, long hours, consistent savings (with/or modest consumption), even in the face of abysmal and deteriorating conditions are needed to return a society to prosperity. More recently, unification has also required sacrifices (primarily from Germans and not from others, as far as I understand it). They may conclude, perhaps rightly so, that if Greeks (and others) cannot pull together and put shoulder to the wheel in dire conditions, they will not do so when others are doing plenty of heavy lifting for them.

“There’s no way the German’s would stop them if their banking system looked set to go under. ”

I’m not sure. I think this postwar experience has made them somewhat less afraid to bite the bullet and do what’s needed. Present news items that Germany is considering how to deal with impaired banks in the event of a Greek default are relevant. Also, letting bankrupt countries leave the euro (for example) will cause the euro to appreciate, but, again, in light of postwar experience (rises from 4.2 DM/$ in 1950 to 1.7 DM/$ in 1999), will this be as big a problem for Germany as often alleged? And will Germany increase imports to correct economic imbalances? No, I think Germans will see this as wasteful consumption (consuming unneeded stuff to fix a trade imbalance), but they may be willing to consume more of their own products if or amended their lifestyles if circumstances require that.

Perhaps some of the confusion is the result of misunderstanding the ‘rationality’ of others. Clearly, without considering the range of German experiences in the past 100 years, one may conclude the actions of an otherwise sensible people to be downright stupid?

In the Great Depression, it was the failure of Credit Anstalt that set off a series of banking failures and debt defaults. In our rerun of sorts, it looks like Jurgen Stark’s rigid adherence to a failed dogma that will set of an even bigger disaster. So much for the idea that economists had learned from financial crises and developed better reflexes.

Has the current social, economical and political framework anything in common with the one of the thirties. Sure a couple of items.

1 – Is the world and the global economy resembling the ones of 1929? No.

2 – Is it US and Europe 1932? No.

3 – Are we on a gold standard? No.

4 – Is the world powerhouse the same as 1932? No.

5 – Is this world powerhouse currently running into deflation? Not exactly. If in doubt when reading Pettis, check Chovannec.

6 – Will we incur a global and massive gold-based deflation with uncontrollable bank runs? No.

7 – Is the dollar – and the Euro – at risk of surviving as reserve currency? I’m glad to secure you. Of course little chance.

You claim that since the world is not on the gold standard, it’s not like 1929. But for the weaker fiscs in the Eurozone, they in effect ARE on the gold standard: they do not have a fiat currency, but one controlled by outside forces that, for whatever reason, are treating the Euro in a fiercely deflationary way. Lacking a money-printing press, the Greeks face harsh deflation, just as if they actually were on the gold standard.

And, in case you hadn’t noticed, the world IS in a major recession, as the world economy was before the failure of the Creditanstalt triggered a world-wide bank run. The question for us now is whether the Greek default would trigger a similar run in the non-fiscally-autonomous economies of the Eurozone. Rationally, Greek debt is far too small in amount to trip up the world economy, but Rule #2 of macroeconomics is that “rational expectations do not count because everyone behaves rationally, and the net effect of multiple rational actors is massive irrationality.”

plus, nobody has any clue how many CDS have been written against greek debt, and then counted on various balance sheets as assets of some kind. like in EConned, where 1$ of debt could become dozens of dollars in losses… am i right?

I do believe that Ambroses’s solution is the least bad of all the scenarios. Splitting the Eurozone in 2 with Germany and followers recreating a new Thaler (rather than DM, since this would be restricted to Germany) and France a

I do believe that Ambroses’s solution is the least bad of all the scenarios. Splitting the Eurozone in 2 with Germany and followers recreating a new Thaler (rather than DM, since this would be restricted to Germany) and France and the med countries keeping the euro. With some appreciation of the Thaler and some depreciation of the Euro. The devil lying in the details the main problem in the last sentence is the “some”, which would be set by Mr. Market.

French banks hit as SocGen ditches assets http://finance.yahoo.com/news/French-banks-hit-as-SocGen-rb-1630217945.html

CNBC at about 11:20 AM had Chris Whalen on. Whalen said that US bank regulators are telling US banks to reduce exposure to Europe, and in his opinion that’s a foolish excess of conservatism because as a practical matter a lender to a major French bank is in effect lending to the French government.

Now here we have from a highly credible source a contrarian view on a timely subject that could be part of a buy case in a demoralized market. The kind of thing you’d think the financial press would want to do.

CNBC cut him off. Amazing, just amazing.

Whalen has a point but he was cut off, I suspect, because he was not “on message”; which is, on both sides of the Atlantic, austerity (for the Many). How’s this for a scenario: The Germans are playing “chicken” with the Juergen Stark resignation, precautions for recapitalization of their banks, etc.; the point being to extract as much from Greece (et al. PIGS) as possible before Greece defaults, plus boost Merkel’s political prospects. (Remember: A few months ago she opposed ECB buying of PIGS debt, but assented at crunch time.) The euro crashes, abetting exporters (such as the Germans). Contagion threatens. The ECB (with German assent)prints euros to safeguard the turf of the eurozone “have’s.” World markets rally, but the euro is still comfortably depressed. Then the real outlier: Due to internal political turmoil. Greece drops out of the eurozone, causing the euro to shoot up, to the consternation of the Germans et al.

I don’t think the Bundesbank or a large proportion of Germany wants a weak euro. They’re savers as well as producers, and their production sells because of quality, at a high price. They seldom are the cheapest. They always wanted a strong DM.

The one that clearly wants a weak euro is Greece. Since they owe euros, they want to repay in cheap currency.

open question: if the troika pulls the plug on greece, why would greece NOT leave the euro?

even if greece announces a debt moratorium, it (a) would still be unable to fund its primary deficit – equal to 10.5% of gdp last year – i.e. instant austerity much worse than what the troika is demanding, and (b) would be unable to rescue its banks, with greek bonds no longer eligible as collateral at the ecb.

leaving the euro would of course mean a big devaluation, competitive gain, etc. but more importantly, it would give the greek central bank control of the greek money supply again, meaning the central bank could finance the continued budget deficit by itself buying up greek debt with newly-printed drachmas.

even if the government promised not to leave the euro, the run on the greek banks would accelerate, forcing the government’s hand. who wants to have their savings devalued?

but here’s the interesting bit – would it not be in greece’s interests to allow the run to continue? i mean, while greece is in the euro, it gives the greek central bank the excuse to print and hand out fresh euro cash to its citizenry, assuming they withdraw cash. and if they transfer their savings to german accounts, the effect would be to increase the ecb’s exposure to the greek central bank ahead of the inevitable massive default.

I like these thoughts. But if the major banks control the Greek government, they will fight to save themselves at the expense of the country’s overall wellbeing. Stage one of their fight to save themselves was the agreement to the initial austerity plan against overwhelming public opposition — from the broad public, not just the government employees.

And that, I think, is what we see played out on the streets of Athens and Thessaloniki and elsewhere, as the public has caught on to this conflict of interests.

“In our rerun of sorts, it looks like Jurgen Stark’s rigid adherence to a failed dogma that will set of an even bigger disaster.”

If there is one point where I disagree with you, it is in the belief of there being a less-than-“bigger” disaster that could be realized, if only the correct policies were to be implemented. I do not think so. Policies make a difference, but at this point, the choice is between the “bigger disaster” being set in motion by Germany, and the utter catastrophe that would ensue if they pushed toward greater union.

The reality is, Greece will never pay back its debts. Nor, in all likelihood, will Portugal, or Spain, or Italy. If Germany were to succumb to cross-European collectivism and fund the social programs of those countries, they would continue doing what they have done the last decades – spend – until they would end up right back where they are now, only with the Eurobonds being the ones whose CDS spreads are shooting off the charts. The general notion that Greece/Portugal/Spain/etc. would soon put their economies back on firm footing, if only given the chance to do so by the Germans, is nonsense based on simple observation of their previous track records. They used formal and informal subsidies by the EU to finance their lifestyles while their real economies continued to disintegrate, and would use direct subsidies through Eurobonds to do the same, until the EU as a whole is brought to bankruptcy.

There is no magical path back to the way things used to be. There cannot be, given the impending demographic implosion in Europe. Germany’s is one of the few economies on sound footing, and they would do best by cutting the ties that connect them to the rest of the sinking fleet. Yes, there will be serious damage to German banks and to exports, but banks can be recapitalized (by printing money if necessary) and new export markets can be found, and that is far less than the total devastation that would be wrought by a Europe-wide default. The periphery, at the same time, would be best served by abandoning the Euro, repudiating their debts, floating their own currencies, and attempting to rebuild their economies based on heavily depreciated local exchange rates.

In order for the Greeks to rebuild on solid ground, they will need to purge the deceit, lies, and obfuscation plague their financial and political systems. The Greek people should use the opportunity to force the individuals and their cronies in the Greek financial system to drink financial hemlock.

What bears remembering in all this is that

1) No one forced the northern banks to lend to the Southern Tier countries

2) No one forced the Germans to engage in a mercantilist “beggar thy neighbor” policy

3) The ECB is not going to ride to the rescue because it remains largely controlled by the Germans

4) European elites are as kleptocratic as their American counterparts

What Schauble and Stark are doing promoting austerism is to try to lock in the gains of German banks and kleptocrats. The European experiment is essentially over. The ideal of Europe was sold to the peoples of Europe but for the European elites it was never anything other than an engine of kleptocracy. The whole periphery from Ireland in the west to the Southern Tier to the East through to the Baltics need to get out, re-establish local currencies, default on their debts to the Core, and take on their local kleptocracies.

You have not shown that the Germans have gained from the euro. They don’t just export within Europe after all.

But aside from that, the euro has to be viable on an ongoing basis. Like any contract realistically, it is not an eternal and unbreakable deal. Default, and its actual costs and consequences, are always on the minds of actual businessmen. If the euro doesn’t work any more as presently constituted, I don’t see that Germany can be forced to continue its support for the status quo.

But they did export to Europe. How long do you think that those exports would have continued without their banks recycling money back to the South?

And that is exactly what the Germans have been trying to do, maintain the status quo, get the countries they drove into debt to honor those debts, no matter what the cost.

It is really more in the interests of the periphery to recognize that the German dominated euro is not an “eternal and unbreakable deal” and that they should move away from it as fast as they can.

You seem to have gotten most of this backwards.

It’s not economics, it’s politics. The economists had their chance in 2008.

Is your Selective Service registration current? WWIII, here we come!

A little confusion in this article. Juergen Stark is telling Ireland to cut their public sector pay. The public sector does not produce things or tradable services, and as we’ve seen in Wisconsin, the public is wising up to the fact that the public sector should not be unionized at all.

The private (productive) sector is where unions should be, not the public.

So “austerity” by slashing public unions (even forcing a lot of those people to look for real jobs) would be a good thing for just about everyone but those particular workers. It does not mean a throttling of productive capacity or deeper poverty for those who are not the lucky public sector union members.

You talk like an economist. Try spending more time in the real world.

That’s a nonanswer.

Just because you don’t understand it doesn’t make it a nonanswer.

If you somehow think that teachers, firefighters, and police provide no worthwhile services and should not be allowed to collectively bargain, go live in Somalia. I’d rather live in a civilized country, myself.

If they can collectively bargain, I should be able to do the same. Otherwise I have to pay too much for their services, relative to what I receive for mine.

In fact, as workers for the public, it’s probably not in the public’s interest for them to have bargaining rights. Maybe there’s a second-order argument for such rights (otherwise the public will irrationally pay too little and hurt itself in the end, or somehow it leads to the revelation of more information to the public in the bargaining process — the latter is laughable, given how secretive the bargaining process is now :). But first one must consider the obvious first-order argument: it’s better for the public (employer) if these employees cannot hold them up for so much money.

Yes I confess to having received economic training. Do you confess to lacking it?

I grew up hearing all these self-righteous arguments you’re making, so I understand them all and their pros and cons. Are you prepared to say the public is better off when the teachers can demand 3% raise every year while the people paying property taxes to support the schools are losing their jobs and the lucky ones still working making less money for more work? Shouldn’t the teachers keep teaching, for less money? Answer that, Mr. Moralist.

And your crippling lack of understanding of demand-side economics is a dead give-away of your formal economic education.

Cutting wages to a substantial body of the middle-class is not a net gain for society. As they cut back on expenses, that impacts all other consumer-oriented industries.

Half of the supply/demand curves are demand curves. Now does it make sense?

Here’s an answer. As long as the banks have a government backed/enforced monopoly on private money creation, then other government sanctioned cartels such as public service unions may be necessary in defense.

Furthermore, I have NEVER voted my pocketbook before but will do so the next election. Any politician who dares mention SS or Medicare can kiss my vote good-by.

“Of, by and for bankers” must stop.

FDR was opposed to public sector unions, and he was neither an economist nor an idealist living in a fantasy world. The reality is that public workers (of which I am one) already have representation at the bargaining table in the form of their elected representatives. If they want better pay and benefits, they can vote for elected representation that will see things their way.

At the same time, they can work to demonstrate their worth and their value to society to better make the argument that they are worth better pay; and certainly part of that would be taking down barriers that keep incompetent and corrupt public servants from being removed from service.

To David’s original post, I agree. The public sector is absolutely necessary, but typically does not add to the productive output of society the way the private sector does. If countries like Greece etc. want to rebuild their economies, the first step will be in strengthening the private sector, which nearly always means a reduction of the public sector.

Another economist. As I said, if you don’t appreciate the service that teachers, firefighters, and police provide — you’re free to move to Somalia. Sorry that teachers, who provide $600,000 a year benefit to the larger economy by educating your children for a substantially more modest salary, aren’t “productive” enough for you.

And what an unvarnished lie — in what way do public employees get to pick their bosses? One vote amongst millions counts for precious little, especially given how most politicians (especially Democrats) bite the hand that feeds them electorally.

Perfect nonsense!

Strengthening the private sector does not require weakening the public sector. In fact, the effect will be quite the opposite –and Greece is in the process of proving it.

Austerity is as effective a solution to deflation as bleeding is an effective solution for anemia…

What barriers are there to removing public servants? Here, I assume you’re referring to teachers. “Tenure” means only that a teacher has to fired for cause. I.e., they are incompetent. Tenure is not sinecure.

It’s to prevent abuses like firing teachers to lower their seniority (and thus salary), since seniority often depends on uninterrupted years of service.

Your comment does not reflect reality. The reality is that tenured teachers and administrators can only be fired for good cause, which means all they have to do is keep their nose clean. Pretty doable for most people. So the employee is well protected at the expense of the employer.

I’ve gotten a tenured principal fired. I know what it takes. The guy should be locked up, and I was still surprised when I learned he was out.

But for private sector workers, you can get fired for working 55 hours a week instead of 60, or making less sales than most other salesmen despite many years of good performance, or because you have a new boss who wants to bring in his own people, or because the company just wants to reduce its payroll, or just because the boss doesn’t like you. This means the employer is well protected at the expense of the employee.

So when the employee is the public, the employer is protected, and when the employer is the public, the employee is the public. The public, except those relatively few members who happen to be private sector employers or public sector employees, are never well protected. Seems backwards to me.

sigh. Public employees buy things. Without money, they can’t do this. This costs private sector jobs. You see -and I know this might be a little too advanced for you, considering it’s only basic Econ 101- but demand doesn’t comes out of thin air (I know!). It comes from people, and people without money can’t demand anything. Just as there must be an adequate demand to support the supply of a good or service, so too must their be an adequate supply of monied consumers to support demand for goods and services, generally.

Also, your analysis of Wisconsin politics is sadly lacking. In the first round of recalls, regarding the safest Republican seats, the Dems got 2 of the 3 seats they needed, and there’s plenty more in the pipe.

Furthermore, how is education not a commercial good or service? What do you think gets people hired in a non-nepotistic job market? Why do you think college grads are paying tens of thousands of dollars for degrees? And what about roads? The quality of roads determines both transport and stock maintenance costs for businesses, and roads are something provided best by public institutions (again, Econ 101 “public goods”). And what about security? While not strictly commercial, it most certainly affects the competitiveness of regions and the lucrativeness of locations. Where would you rather open a storefront; in New York City with its highly paid, well-manned, unionized police force, or Appalachia, the land of meth, blood-feud, local corruption, and the “right to work”? Don’t kid yourself into thinking that considerations like that have no relevance to business strategies or success.

Your insults don’t hide the fact that you are, in the main, wrong.

A few consumers are also public sector employees, but not most. If most were public sector employees, God help us, we would have no economy left.

Or is this sort of mathematical, systems-level thinking the thing you found so difficult that you did not do the studying required to understand the economic questions in this way? How do you like that insult, by the way?

When the only people with non-outsourceable jobs left are working for the government perhaps they should have a union. Lets face the fact that the GOP has spent the entirety of my life trying to destroy the middle class granted by unions. First the laborers, then the supervisors, then the managers, then the engineers (Boeing moving to South Carolina and outsourcing their high tech manufacturing to the Red Chinese is efficiency written in a suicide note), will the vice presidents be next? Where will the McDonalds and WalMart unions begin if there are no unions allowed, no tradition preserved?

Genius economists and conservative activists have destroyed a once great country with the help of prostrate centrists.

With respect, no. If the only jobs left are government jobs, our economy is dead. We have been killed by globalization, assisted by the inexorable force of the WTO and other international treaties.

The only way to revive our economy is to stop most all of the outsourcing, importing of goods, and importing of foreign workers (both illegals and H1Bs). Basically close the borders and start over as an independent country. Once that’s going again, we can reconsider trade and immigration policy, one small step at a time, but that’s some way in the future. We have internal work to do first.

Or maybe we should give up and say USA doesn’t matter any more, just corporations.

It is a mistake to ascribe the elite or even government too much power. Jobs are outsourced because of labor cost disequilibria which provide a powerful incentive for work hours to flee to low cost production centers. As soon as domestic unskilled labor is willing to work for $0.10 / hr., I am sure the trend will reverse itself. As this seems unlikely, it will not pay to be unskilled labor in this country for some time to come. In the mean time, I suggest the best thing we can do is hope the east Asian labor markets follow the Japaneese and Koreans. They will enrich themselves until they are no longer a competitive problem. At some point the cost savings will dwindle to the point that it is no longer worth it to deal with Chineese corruption, and the boom will dry up.

We can only hope that the environment can withstand 2 billion more people with western consumption habits.

Outsourcing due to wage arbitrage is a canard that’s been debunked on this site about a million times. For manufactured goods, labor only accounts for around 10% to 15% of the cost. Against this are loss of quality control, poor responsiveness to changing market conditions, general loss of managerial control, and transportation costs. This doesn’t even touch on externals like poor working conditions and environmental degradation.

Also I am not sure what your definition of unskilled labor is. A lot of manufacturing requires a skills set, just not necessarily a college education.

“…..the public is wising up to the fact that the public sector should not be unionized at all.”

Thank you, David, for saying something that needs saying. Public sector employees get generous salaries, generous benefits, good working conditions, almost total job security, and they usually work for a monopoly employer. Why the hell do THEY need a union?

Let’s give them a COLA raise every year, be done with their games of threatening to shut down essential services, and get on with the business of unionizing the millions of low-wage, abused workers in the private sector.

Nice bias here:

“The public sector does not produce things or tradable services, and as we’ve seen in Wisconsin, the public is wising up to the fact that the public sector should not be unionized at all.”

Actually, in Wisconsin, the public protested loud and long against the proposal. The political party in charge basically used fraud to pass and enshrine the law [now stop me if you’ve heard that story before].

“The private (productive) sector is where unions should be, not the public.”

And that’s where they might be, if corporations had not fought a decades long war to destroy them as an impediment to profits.

“So “austerity” by slashing public unions (even forcing a lot of those people to look for real jobs) would be a good thing for just about everyone but those particular workers. It does not mean a throttling of productive capacity or deeper poverty for those who are not the lucky public sector union members.”

Most of the local government jobs I am aware of (teaching, police work, firefighters, road crews, etc.) are doing real jobs. And one of the lies of the effort to destroy the public unions is that they don’t contribute to their benefits; they do, but by taking pay rates that were, prior to the demolition of the private sector unions, lower than their counterparts in return for those benefits and better job security.

And they are not lucky. In the current recession, public sector workers are still losing jobs while there is a slight uptick in private sector work.

At the end of the day, in addition to productivity, you also need consumption, and in the race to the bottom in private and public sector pay (except for those at the very top), that has been in steady decline for decades.

Now, on the other hand, if you wanted to complain about the spiraling salaries for the manager/political appointee class in the public sector, and contractors overpaid for doing what were once public sector jobs, you might gain a convert…

Sad to say, they actually think they can exist without the rest of society. Remember that Citigroup analysis arguing that, because most growth in consumption over the last decade had come from the wealthiest sectors of society, that they could just ignore the rest of society and the economy would be just fine? Well, it looks like Europe’s about to find out if there’s any truth to that philosophy.

Of course, as any intelligent person would realize, that thesis has already been proven false through the GFC. Most of that consumption and wage growth by the highest echelons had been achieved, literally, by stealing the rest of society’s only remaining source of equity (houses). Once the investment-driven bubble in housing prices burst, it did rather severe damage to plenty of businesses and personal fortunes. So far the tip-tops have managed to preserve their lifestyle and avoid paying attention to the havoc they’ve wrought by using the crisis to justify cannibalizing the wages and jobs of lower and middle class citizens while simultaneously picking their pockets through the legislatures, but how long can they keep that up before no more blood can be squeezed from that particular turnip, and the bottom begins to fall out?

Per the BLS (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.nr0.htm) in 2010 union membership in the public sector stood at 36.2% and in the private sector at 6.9%. Breaking down these numbers further, in 2010, union membership was 42.3% in local government (4.67 million: think teachers, police, and firefighters); 31.1% in state government (1.969 million); and 26.8% at the federal level (984,000). That is 7.623 million in the public sector vs. 7.092 million in the private sector. The majority of union members are in the public sector.

So when we see people wanting to weaken or do away with public sector unions, what they are actually doing is wanting to destroy unionism’s last bastion, the public sector union. Fed anti-inflation policy, tax policy, deregulation, and anti-unionism have kept wages of ordinary Americans flat for 35 years even as they fueled massive transfers of wealth away from the middle and working classes to the rich. When you see people attacking public sector unions, you know which side of the class divide they are fighting on.

They are on the side that needs to be spending A LOT of their own money to feel safe walking to the end of their driveway. Every day.

A new Creditanstalt event, you say…

It might be, unfortunately. But then again, it might not.

Because as bad as all the bickering within the Eurozone during the past three years has been, it’s not like anyone here with half a brain or more has been expecting anything else than a PIIGS default to happen. Which means that I would expect European banks to be a bit better prepared than Yves gives them credit here. Sure, if Greece defaults, there will be major upheavals. And problems. But in my opinion, all the seeming financial asshattery that has been going w/r to PIIGS sovereign debt on over the past two, three years has been a deliberate buying of time. As in: “we know we are going to crash no matter what, so brace yourself”. And the time that was bought (hopefully) gave most banks the time to brace themselves in a fashion that avoids the worst.

Now I’m not the sort of person who has a very high opinion of elected officialdom within the EU on a good day, and I frankly think that a sizeable portion of them are vile scum (or even beneath that evolutionary level, such as most of Greek officialdom). But still, this buying of time made some sense, even if it was the standard knee-jerk reaction they did without too much intellectual underpinnings as to why they did it.

It’s not 1931, folks. Don’t keep looking for certain things to happen again in a totally changed world. That is not to say that no bad things are going to happen, but a complete systemic crash… it’s just not that likely, fortunately. Not at this stage, in any case. The world is much bigger than the Eurozone these days, and much, much more diverse than in 1931.

A.

The US housing bubble went kerblooey on August 9, 2007. So the banks had more than a year to prepare for the meltdown that began on September 15, 2008 and it happened anyway. It would have forced them all into bankruptcy had it not been for Bernanke’s massive bailouts. Many of those programs helped European banks stay afloat. We don’t need to go back to 1931 for an example. We had one just 3 years ago. And the moral of that story was that even though banks had time to prepare and many of us in the blogosphere were warning that their house of cards was about to go, they were caught like a deer in the headlights of an oncoming semi. The truth is that US and European banks were insolvent back then, and they are insolvent now. That’s where the whole zombie terminology came in. They’re dead but as long as governments don’t call them on it they keep going, that is until another crash exposes again their fundamental insolvent condition. Indeed it is the fact of that insolvency that sets the conditions for the next crash and makes it inevitable.

@Hugh:

All the rampant boardroom stupidity out there notwithstanding, I’d wager that banks are a lot better prepared for any sort of calamity than in 2007/8. Back in 2007, no one seriously believed that in reality, things could get that bad that fast. Or at least, no one on the executive level: by and large, these people are not selected for their critical thinking skills, or their willingness to challenge the status quo (which goes a long way to explain the parade of intellectually mediocre egomaniacs in today’s CxO world).

However, not even that sort of person can be in denial nowadays that the entire world economy is much more fragile than anyone dared to openly admit prior to 2007. And as (in the classical sense) intellectually feeble as your average CxO is, they usually do have fairly reasonable corporate survival skills. As opposed to actual brains and character, ruthlessness and survivability are traits these people are actively selected for.

And all Golden Parachutes notwithstanding, no-one in such a position wants to have his bank blow up while he is at the helm. Huge losses are something else, that is something you can dump on the shareholders and customers. But a systemic crash? That would make all those nice stock options and bonus packages worthless. So I have the very firm assumption that the banking world spent most of its top-level strategic planning energy during the past 2-3 years on preparing for the coming “crash”. Which will be a crash all right (with Greece and other PIIGS defaulting), but it will be survivable. Some people will lose money, but at least it will be over afterwards. And there will not be a complete melt-down.

All the big banks assume there will be an ultimate government backstop. This means basically they don’t have to plan and they don’t have to reform.

We already have seen in 2008 how they react to a meltdown. Far from being chastened, they use it as an opportunity to increase their control of the economy and government.

Germany is discovering what Japan learned 20 years ago – too much success is not tolerated.