Yves here. This post includes some details on the background of the Libor scandal that were new to me and I believe readers will find informative.

By Satyajit Das, derivatives expert and the author of Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (2011). Jointly posted with roubini.com

The scandal surrounding the manipulation of LIBOR sets raises a number of issues. In the first part of the two part piece, the known facts are outlined. In the second part, the broader implications of the episode are discussed.

Fix…

Depending on context, the word “fix” can mean “set” or “determine”, “manipulate” or “rig” as well as “repair” or “correct”. “In a fix” means to be in difficulty. In colloquial use, “fix” is a dose of an addictive substance that is habitually consumed. The current furore surrounding manipulation of money market rates contains all these meanings and more.

An objective mechanism is needed to set money markets rates used in a variety of instruments. A number of traders at leading banks submitted false rates seeking to manipulate the outcome. Banks are in a fix. If the current arrangements are unsatisfactory then it will be necessary to repair the mechanism.

In a Fix…

In June 2012, UK and American authorities fined UK’s Barclays Banks £290 million (US$450 million) for manipulating key money market benchmark rates, such as the London Interbank Offered Rate (“LIBOR”) and Euro Interbank Offered rates (“EuroIBOR”).

The settlement follows a lengthy investigation into fixing money market rates by regulators, under way for at least 2 or more years.

In 2011, Swiss bank UBS disclosed that as part of the investigation it had received demands for information on “whether there were improper attempts by UBS, either acting on its own or together with others, to manipulate LIBOR rates at certain times”. The Wall Street Journal in May 2008 published a study suggesting that banks might have understated borrowing costs. An academic study published the same year found that LIBOR had remained low whilst bank risk was increasing. Individual bank’s rate quotes remained very close, surprising given divergences in perceived credit quality.

The exact circumstances remained unclear until the UK Financial Services Authority (“FSA”) released detailed evidence indicating that Barclays had manipulated rates. Barclays’ Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) Robert E. Diamond Jr. and Chief Operating Officer Jerry del Missier were forced to resign. Barclays’ Chairman Marcus Agius resigned but agreed to remain temporarily to find a new CEO.

An unknown number of traders and inter-bank brokers have been dismissed, suspended or put on leave by their employers as a consequence of the investigations. Institutions affected allegedly include Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, Royal Bank of Scotland and Citigroup.

The Fix…

LIBOR stands for the London Interbank Offered Rate. This originally reflected rates at which banks in the Euro-dollar market lent surplus liquidity to each other. As the market grew, an accepted pricing benchmark was required.

In the 1980s, the British Bankers’ Association (“BBA”) working with major global financial institutions and regulators, primarily the Bank of England (“BoE”), created the BBA rates. Initially, these were standard only for interest rate swaps (known as BBAIRS terms). Demand for a standard benchmark for instruments based on money market rates led to the creation of the BBA LIBOR fixings, which commenced officially around 1 January 1986 following a trial period commencing in December 1984.

LIBOR is defined as: “The rate at which an individual Contributor Panel bank could borrow funds, were it to do so by asking for and then accepting inter-bank offers in reasonable market size, just prior to 11.00 London time”. Each bank must submit a rate accurately reflecting its belief about its cost of funds, defined as unsecured interbank cash borrowings or fund raised through issuance of interbank Certificates of Deposit (“CDs”), in London as at the relevant time.

There are 150 different LIBOR rates published every day, covering 10 currencies (including US$, C$, A$, NZ$, Euro, £, yen and Swiss Francs) and 15 maturities (ranging from overnight rates to 12 months).

There are between 8 and 20 banks on each currency panel. Each bank provides its quote. The top and bottom 25% are ignored and the remaining quotes are averaged (the inter-quartile mean) to arrive at the quoted LIBOR. The process is overseen by the BBA but daily calculations are undertaken by Thomson Reuters, which publishes the rate after 11:00 a.m. generally around 11:45 a.m. each trading day London time.

The rates are a benchmark rather than a tradable rate. The actual rate at which specific banks will lend to one another varies. The rate also changes throughout the day.

LIBOR is used for loans, bonds (such as floating rate notes (“FRNs”)) and derivative transactions. Derivatives that use LIBOR to determine payments include various futures and options contracts, forward rate agreements, interest rate and currency swaps and various interest rate options.

The exact volume of transactions using LIBOR is unknown, as most are over-the-counter (“OTC”) bilateral transactions. Estimates suggest that LIBOR is used to establish the interest costs of $10 trillion of loans, $350 trillion of OTC derivatives and over $400 trillion of Euro-dollar futures and option contracts traded on exchanges.

First Fix….

Pre-2007, Barclays manipulated rates in order to obtain financial benefits. Subsequently, during the global financial crisis (“GFC”), Barclays manipulated rates due to reputational concerns.

The pre-2007 episode relates primarily to mismatches in banks’ asset and liabilities. For the most part, banks simultaneously borrow and lend money. In derivatives, they both receive and pay the same or similar rates.

For example, a bank may have borrowed 1 month money to finance a loan where the rate is based on the 3-month rate. Derivative traders may receive 3-month LIBOR but pay 6-month LIBOR. Mismatches arise from timing differences; a bank may have a transaction pricing of 3 month LIBOR on one day offsetting a position pricing off 3 month LIBOR the next day or a few days later.

Mismatches may be deliberately created to increase profit. Mismatches also result from the natural flow of customer transactions.

Mismatches (known as reset risk) can be managed by entering into transactions such as reset swaps. A bank might pay 1 month LIBOR against receiving 3 month LIBOR. Hedges are expensive and not always readily available.

The incentive to manipulate rates for profit arises from these mismatches. The evidence is consistent with this pattern of activities.

On 13 September 2006, a trader in New York writes: “Hi Guys, We got a big position in 3m libor for the next 3 days. Can we please keep the libor fixing at 5.39 for the next few days. It would really help. We do not want it to fix any higher than that. Tks a lot”. On 13 October 2006, a senior Euro swaps trader states: “I have a huge fixing on Monday … something like 30bn 1m fixing … and I would like it to be very very very high ….. Can you do something to help? I know a big clearer will be against us … and don’t want to lose money on that one”. On 26 October 2006, an external trader makes a request for a lower three month US dollar LIBOR submission stated in an email to a trader at Barclays “If it comes in unchanged I’m a dead man”.

Traders sought to fix the rate sets to increase the firm’s profits and ultimately their own bonuses. Following the request of 26 October 2006, Barclays submitted a 3- month US dollar LIBOR quote that was half a basis point lower than that the day before. The external trader thanked the Barclays’ trader: “Dude. I owe you big time! Come over one day after work and I’m opening a bottle of Bollinger”.

Second Fix….

During the GFC, the FSA alleges that Barclays sought to manipulate LIBOR to minimise reputational concerns about its financial position.

Money market conditions were extremely difficult from late 2007 until early 2009 when massive central bank intervention alleviated funding pressures. There was little or no trading in money markets, especially beyond 1 week.

Individual bank funding activity and LIBOR quotes were intensely scrutinised. There was focus on any banks which were accessing emergency central bank funding, such as the BOE’s emergency standby facility. During this period, a high LIBOR post was interpreted as a sign that a bank was struggling to raise deposits leading to withdrawal of money market limits exacerbating funding difficulties. Equity markets too reacted savagely, selling bank stocks at any sign of funding stress.

The uncertainty was evident in the excess reserve balances held by banks with central banks as institutions assumed the worst about their peers. It was also evident in the difference between 3 month dollar LIBOR and the overnight indexed swap rate, which is an indicator of banks’ willingness to lend to each other. This spread peaked at a record 364 basis points on 10 October 2008, compared to an average of 10 basis points in period 2003-2008 and 45 basis points since 2008.

Banks also found it difficult to accurately calculate exactly rates because of illiquid money markets. Submissions became a guess of the level if a market existed, based on discussion with other market participants and checking competitor’s previous submissions.

The FSA Report refers to media reports that Barclays had been posting high LIBOR rates and market concern about the bank. The BoE was also concerned leading to a number of discussions between official and Barclays’ management. BoE concern is understandable given the difficulties of other major UK banks, such as RBS and Lloyds/HBOS.

An October 2008 file note written Barclays’ CEO Mr. Diamond (curiously one of only 3 he ever wrote) states that BoE Deputy Governor Paul Tucker advised that the bank’s high LIBOR submissions were gaining the attention of “senior figures” in Whitehall. Mr. Diamond recorded that Tucker felt Barclays did not need to keep posting such high LIBOR fixings, intimating that “it did not always need to be the case that we (Barclays) appeared as high as we have recently”.

Barclays would have been concerned that incorrect price signals could set off panic and massive funding pressures.

In a Bloomberg Television interview in May 2008, Tim Bond, a former Barclays Capital executive, indicated that banks routinely misstated their borrowing costs in the BBA process to avoid the perception that they faced difficulty raising funds during this period. This is consistent with a 2008 Bank for International Settlements (“BIS”) report which questioned the accuracy of LIBOR quotes, stating that they could be influenced by “strategic behaviour” with banks “wary of revealing” information that could signal stress.

While the banks manipulation for the purposes of financial gains is indefensible, Barclays’ officials argue that during the crisis it acted with the explicit or implicit agreement of the BoE.

Damage…

While there is little doubt that incorrect rates were submitted, the effect is more difficult to establish. A single high or low quote would be eliminated from the calculation.

Collusion between the banks could affect the rate. The FSA Report suggests that Barclays worked with other banks. In court filings, Canada’s Competition Bureau disclosed that one bank had confessed to participating in a conspiracy to manipulate LIBOR to affect the price of derivatives globally, involving employees of HSBC, Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan, RBS and Citigroup as well as a money market broker ICAP.

Even without collusion, small changes in submissions can affect the LIBOR set. Setting rates very low or very high may ensure that the bank’s submission is excluded, allowing another rate to be included in the calculation. If a bank sets rates very low then it ensures that lower rates are included in the calculation decreasing the average. Similarly, setting rates higher pushes higher rates into the calculation increasing the average.

The ability to manipulate rates depends on the number of banks on the panel and the dispersion of the original submissions. A small panel makes the rate easier to manipulate. Where the submissions are highly dispersed, it may be easier to influence the final outcome, even without collusion. The differences between rates around the cut-off point for inclusion are critical. It is helpful to know what individual submissions are, although the previous day’s quote may provide a reasonable proxy.

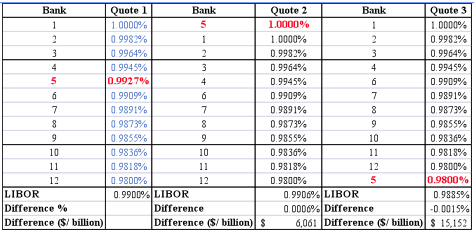

Table 1 sets out an example which illustrates how rates are affected.

Table 1 sets out an example which illustrates how rates are affected.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Table 1

Effect of Submission Manipulation

In the following example, assume quotes are as follows:

Quote 1 – original bank submissions.

Quote 2 – Bank 5 manipulates the quote by increasing its submission.

Quote 3 – Bank 5 manipulates the quote by decreasing its submission.

In all case the top and bottom 3 quotes (25% each) are ignored with the LIBOR rate being determined by the arithmetic average of the remaining 6 quotes.

Differences are given in percentage and dollar amounts calculated for a full year assuming a principal of US$ 1 billion.

In the first case, dispersion (range) of 2 basis points between top and bottom quotes is assumed.

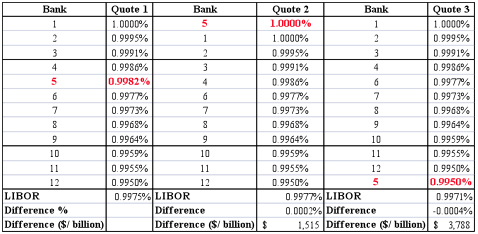

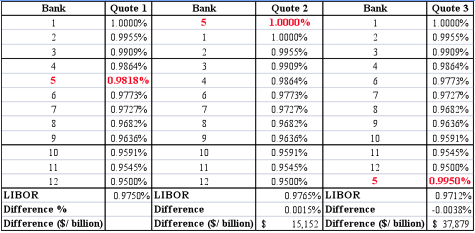

If the dispersion decreases (increases) the effect on LIBOR similarly decreases or increases. The following Tables assume dispersion of 0.5 and 5 basis points respectively.

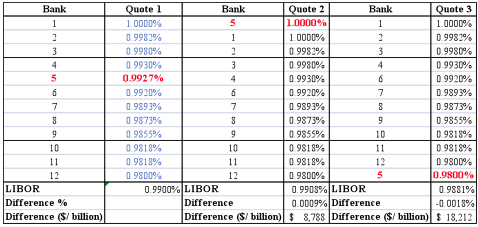

If there is a large difference (jump) between rates around the cut-off point for inclusion, then the effect on LIBOR is exacerbated. The following Table assumes a dispersion of 2 basis points respectively but larger difference around the relevant points than the previous example.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Small changes have a material impact in dollar terms where large sums are affected. A 1 basis point change on US$ 1 billion is equivalent to US$100,000 per annum. Assuming a total of US$800 trillion of affected transactions, the potential amount is US$80 billion per annum or $220 million per day. Actual damages would be significantly lower.

Rates fixes are for shorter term, 1 or 3 months. Where they reflect spread between say 1 month and 3 month rates, the amount involved would be smaller.

Damage & Damaged…

LIBOR is not used for all financial transactions. They are primarily used in wholesale loan transactions and derivative transactions. Retail or small business loans are based on the bank’s own base rate reflecting its funding cost. Bank retail deposit rates are rarely based on LIBOR.

According to the US Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the proportion of US mortgages priced directly off LIBOR is estimated at around 2-3% of all mortgages, about 900,000 loans totalling $275 billion. The proportion of UK mortgages priced off LIBOR is similar. In the US the predominance of fixed rate mortgages makes a money market benchmark like LIBOR irrelevant.

BBA LIBOR is not used in some markets at all due to history or differences in market convention such as settlement protocols. Derivative and loan transactions in Australia are priced off the indigenous A$ bank bill rate (BBSW). Transactions in the US use a variety of rates including US Prime Rate or US Commercial Paper rates.

Manipulation could indirectly affect interest rates. Changes in a bank’s wholesale funding might affect its lending and deposit rates. Retail mortgages and credit card loans are refinanced through securitisation transactions, which are linked to LIBOR.

Determining the affected parties is also complex. During the GFC, low rates benefitted borrowers but penalised depositors. Low LIBOR sets penalised payers of fixed rate in an interest rate swap but benefitted receivers.

In derivative transactions, there may have been transfers of value between banks. One swaps trader states that a large bank is on the other side of a fix with opposing financial interests. Individual desks or traders within a bank may have different interests in a particular LIBOR set. There will also be differences between banks that contribute to the LIBOR fix and those who do not.

End-users, corporate or retail borrowers and investors, would be the major parties affected.

A perverse outcome is likely in litigation. As banks act as intermediaries in the main, there would be a transfer of wealth between parties. Losers will sue banks who will be unable to recover their losses from the parties that may have benefitted.

Clients suing banks is now passé. The sight of banks suing each other seeking compensation promises ribald entertainment. Goldman Sachs (who do not contribute to the fix) claiming that they were innocent victims and unsophisticated investors may provide a suitable coda to the episode.

Lawyers running our big banks……

Glass Steagall comes back with a vengance….

GRAMM,GREENSPAN,RUBIN fleeing to Switzerland…

BIG BANKER ALERT….TIME FOR PLAN B…

PLAN B…flee to Switzerland with GRAMM,GREENSPAN et.al.

before getting lynched here.

TEA PARTY PLATFORM…more deregulation needed

Why is ($,€..etc) funding cost determinined by a group of gentlmen in london?

Why are US banks allowed to sign agreements based on this “survey”, the rules of which are beyond the scope of US law?

From what I understand, UK authorites are “cooperating” in the investigation. The US, EU etc. investigations have no force of law, only the cooperation they are granted by the “crown”.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s already a jolly good show, but I have my doubts that anything of any value will be offered.

So far, they’ve thrown one american banker back across the pond. British humor. I heard, in the news of the world, the queen laughed so hard she farted.

Once upon a time British banking was a “gentleman’s club”, that is, it was run by men of honor whose word was of no little consequence. Their word was their bond.

Needless to say, those days are gone forever.

In their place, the city of London is run by avarice and cupidity – a financial center, like Wall Street, where one’s word is “conditional” or “circumstantial” – the condition or circumstance dependent upon one’s “position” in any given market.

Iow, it’s a free-for-all where regulation-lite is the rule, thus the cats away and, of course, the mice will play.

That bank management thought that Libor could NOT be fixed, or that they remained oblivious to the fact that it could be so easily fixed (which was so evident when one understands the offer-mechanism) is beyond comprehension.

Word around the blogosphere indicates that the specific individuals involved will be indicted soon. But if management negligence is a fact in the matter, which many think is the case, then this class should not walk away unscathed. Not again, not like after the Subprime Mess stateside.

Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.

What’s really going on here? One hundred (more or less) overage fraternity boys gambling trillions of other people’s money for their own benefit and at everyone else’s risk. The idea that OTC derivatives increase ‘liquidity’ and provide ‘risk management’ is the biggest con in financial history. The only serious question is whether our elite will keep the con going until it destroys everything.

Yes, but it would be almost gauaranteed to push other quotes into or out of the rate calculating band. If there’s a too low quote floating around in there, you can probably shove it down and out by posting the highest bid.

Doesn’t it suffice therefore to have all posts “blind” and all required within a certain short period of time or not at all?

Very helpful to have clarification on the technicalities.

However, a number of points are not being addressed.

1. The evidence available to so far suggests that, prior to the onset of the financial crisis, Barclays was a ringleader – particular in the collusive fixing of EURIBOR, where owing to the greater size of the panel it would be more difficult to make significant differences to rates without traders and submitters in different banks acting together.

However, the evidence at the moment is consistent with the possibility that, prior to 2007, routine LIBOR fixing was a small scale phenomenon, in which corruption at Barclays was spreading out to other banks. It is also consistent with the possibility that the 2005 cut-off point chosen by the CFTC, DoJ, and FSA is purely arbitrary – and that, as indeed the Economist (of all papers) appears to suggest, such fixing had started back in the Eighties: almost as soon as the LIBOR system started.

The question of whether corruption before 2007 was recent and small scale, or long-standing and practised by many banks, is fundamental. People seem to be forgetting about it. And while it is clear that the transactions which were fixed related to very large sums — $80bn. in one case – it is not clear how many of them there were. It could be that the cases of fixing discussed in the settlement documents are the major part of those that took place; it could be that they are a tiny sample of these. So far, we do not know, and the fixation on the delinquencies of banks during the financial crisis seems to be preventing people asking this and other critical questions about events before the crisis.

2. The evidence of the documents from these investigations, however, also very clearly suggests that after the onset of the financial crisis, Barclays was not leader but laggard. Moreover, at this point what was at issue was not simply individual banks acting out of concern for their reputation – it was ‘pack’ or ‘herd’ behaviour, with banks not wanting to stand out, and being engaged in maintaining a collusive fiction that interbank lending was proceeding as normal. This kind of ‘herd’ behaviour is endemic in financial markets – and the fact that it is largely ignored by economists is another mark of how fundamentally flawed the whole discipline is.

Through the financial crisis, the evidence suggests that although Barclay did underreport its borrowing costs, it did so with reluctance – and its employees were candid with authorities on both sides of the Atlantic that they were being pushed into a course of action they disliked because it was too dangerous to tell the truth when everybody else was lying. And this is not actually an argument to be dismissed lightly.

Crucial background to the key e-mail exchange between Tucker and Diamond on 29 October 2009 were exchanges between Tucker and the principal private secretary to Gordon Brown, Jeremy Haywood, over the preceding days. These related to the fact that UK LIBOR spreads were not falling as fast as the U.S. The rumour reaching Downing Street was that sterling LIBOR was high ‘because Barclays are bidding it.’

The concerns behind Tucker’s suggestion to Diamond that Barclays submissions did not need to be as high as they had recently been could have related to two separate problems. It could have been that both Downing Street and the Bank genuinely thought that Barclays was having funding difficulties. It could also have been that they thought that its funding difficulties were no worse than those any other U.K. bank was experiencing, but that its refusal to join in the collusive fiction was helping to create a situation where U.K. banks looked as though they were failing to recover from the financial crisis.

The possibility that the markets might perceive that the U.K. banks were bust, while their U.S. counterparts were not, could very well have caused acute alarm in quite reasonable people.

In the event, a plausible explanation of Diamond’s behaviour at this point was that he was in the final stages of negotiating a multi-billion pound investment by Middle East wealth funds, which meant that Barclays could escape from its financial problems without having to go cap in hand to the BoE and the Government. That Barclays was playing for this kind of outcome may have had to do with Diamond’s reluctance to join in the collusive fiction in the immediately preceding period. Whether it accounts for the reluctance earlier on would seem a moot point.

3. Contrary to the impression some people appear to have formed, U.S. funding costs were not determined by a group of gentlemen in London. All these panels were international, and if there is a shred of evidence that they were biased towards U.K. banks, nobody has so far produced it. One of the most interesting panels, in fact, is that dealing with Yen LIBOR submissions. The fact that a range of Japanese banks are under investigation is itself extremely interesting – as are the claims made in the wrongful dismissal suit brought by the former RBS trader Tan Chi Min against that bank in Singapore. According to his submissions, the fixing at RBS happened with the collusion of senior management – and moreover, the hedge fund Brevan Howard, and other clients, put in requests for LIBOR to be fixed.

What has however not yet been clarified is whether Tan Chi Min is suggesting the rate-fixing he alleges was simply a phenomenon of the period following the onset of the financial crisis or whether it began earlier – and if so, how much earlier. This remains a critical question, not simply in relation to British banks, but in relation to banks worldwide.

A couple of points:

-I don’t know anyone who calls those swaps “reset swaps”. Everyone I know calls them basis swaps (and they are relatively liquid, especially 3/6). OIS swap is also basis swap, although that has compounding in it so it’s more complicated)

– fixed mortgages and term deposit rates ARE set using LIBOR, or more specifically are always swapped to LIBOR + spread (which means that shape of the LIBOR curve affects the rates).

– which leads me to another; one-off manipulation is likely to lead to minimum impact on LIBOR curve; protracted under-reporting WILL have impact. If nothing else, it will impact the futures market, which will impact the short-end of the curve (it can also impact the long end of the curve, but that’s more complicated and harder to show). Impact on LIBOR curve then has impacts on pricing of just about any derivatives, because if nothing else it’s commonly used for discounting (it’s actually more complicated, but for simplicity). That would efect even things like equities, FX, commodities etc. etc.

If someone could show that persistently low rates did affect curve to some reasonable extent, the total amount affected would baloon beyond anything people talk right now (low LIBOR curve = lower discounting = higher cost of hedghing FX, commodities, equities etc..)

vlade,

very interesting.

What is not clear to me in relation to the manipulation prior to 2007 is whether there is reason to believe that the actions of traders and submitters — and their confederates in other institutions — had any consistent bias. From what you say, it would seem that the situation would be materially different, if the overwhelming preponderance was in a single direction, from if submissions were too high, and some too low.

As to mortgages, a matter about which I am curious is whether if indeed there was a significant influence on these, it would have been of the kind which makes it possible for those affected to take legal action.

My suspicion at the moment is that the legal actions will concentrate on the period after 2007, because the scale of distortion in the submissions is so much greater, so the pickings would be correspondingly greater.

I am afraid that the question as to whether the manipulation prior to the financial crisis goes back a long time before 2005, and affects a great many banks other than Barclays, may not be given the attention it deserves.

I believe it unlikely that before 2007 there was a consistent bias – most likely it was reset risk/position driving the bias (and I’d point out that even a single basis point might make tons of difference enough in option derivatives, which seem to have been ignored so far).

I believe that that had very little to no impact on the LIBOR universe – likely within the expected “noise”. It should be possible to show that if someone had the time to run the stastical tests.

Pre 2007 manipulation should be clearly criminal, altough I doubt there’s anytghing anyone will be able to do on it – in the worst case, I’m sure that at least in US they can use First Amendment since LIBOR is an “opinion” (belief). How many rating agencies have been successfully sued in US? (there might, just might be precedent brewing in Australia…)

With the 2007 bring-it-down, it’s harder, a it could be argued (especially w/o framework which makes it criminal) that reporting lower rates was preventing a run on the bank, thus in the interest of everyone. Lowering the rates (or the curve) could also benefit number of clients (including mortgages), so should those disgorge the gains?

My understanding of the legal position – which may be wrong – was that one of the problems for banks was quite precisely that they would have no recourse to seek reimbursement from those who had benefited from LIBOR fixing, but could be sued by those who had lost.

I think the question of whether a defence on the basis that underreporting was necessary because an accurate presentation of the extent of the mutual distrust between banks ran excessive risks of creating panic is a very interesting one. In the FT Alphaville discussion of Nomura’s note on the implications of the civil suits, on which I think you commented, the journalists seem sceptical as to whether it would wash.

Precisely because the situation is unprecedented, I suspect the legal position is not at all clear. The arguments in the U.K. have had a certain air of unreality, because although I think there is good reason to suspect that Tucker was encouraging Barclays to come into line with the ‘pack’ on precisely these grounds, neither he nor anyone else is going to state the argument explicitly. An e-mail Tucker sent Diamond on 26 May 2008, in which he explains that the ‘sense’ was ‘similar’ among the relevant people in HSBC, RBS and Barclays, and he was encouraging ‘contact’ among the ‘peer group’, suggests to me that he was trying to get the banks to operate as a pack.

This could well have made sense, at the time, because higher submissions could both have exposed the bank making them, and also risked exposing the fact that LIBOR had become a kind of collusive fiction.

If the defence is used, and the case comes to court, then of course Tucker – and also other officials, and not simply in the U.K. – would be exposed to much more serious cross-examination than they were given by the Treasury Select Committee.

A point which emerged in the CFTC document, meanwhile, was that the ‘primary Euribor submitter’ was ‘the expert on the Euro money markets’, who ‘had 20 years experience in the London money markets and had been with Barclays for over 35 years.’ I would need to go back and check, but the impression given generally, I think, was that LIBOR submitters were people of some weight.

On the face of things, it seems to me unlikely that they would have had the kind of direct personal interest in the fixes that traders would have had. Accordingly, questions are raised about the credibility of the ‘bad apples’ theory which is tacitly endorsed in the settlement documents. It would seem that, unless the reporting systems in the bank were quite calamitous, senior management must have known what was happening.

Oh, I have zero doubt that the senior management knew (and that Tucker’s hope to be next BoE gov is gone).

I just really wonder how much recourse there is, given how LIBOR works – which in and of itself is a prime reason to reform it, but that’s a different discussion.

Lowering the rates caused direct impact on financial institutions not party to the criminal conspiracy.

Such as Schwab. Which is suing for compensation.

Caveat emptor. LIBOR is not traded, is a “survey of opinion”, etc. etc. If you enter into contracts that reference it, you’d better understand what it is. In fact, your fish and chips shop may have better chance for compensation (albeit based on misseling rather than “manipulating”).

Again, how many successfull lawsuits there were for mis-rating releated losses? There’s evidence ratings were manipulated too, pretty clear one. The parallel is clear – you have piece of opinion that is supporting a very large structure.

No-one seemed to care that undermining the quality and independence of that “opinion” can bring a large part of the spectacle down, and looking at the ratings “fix”, I’ve no great hopes for the LIBOR one.

VLADE, thanks fr the posts. Really know yr stuff. cheers

So the LIBOR note was only one of three file notes that Diamond ever wrote?

I would be interested to know what the other two were about!

Libor is not a price quote, it’s an offering rate. If you an offering rate as a pricing metric your are being a bit foolish.

If you ask me for an offering rate opinion, I can assert any damm number I care to and this what has transpired.

A low rate will result in a benefit to a borrower and a detriment to a lender, but most importantly, a low rate will have the effect of inflating all financial assets that have libor as a pricing metric. There’s the fraud.

A larger issue here is why ever would otherwise competent people price financial instruments by using something other than a transaction price?

If the system, since 1980, to calibrate LIBOR, was effective because the change in rates quickly balanced out over the system (because the system was dynamic) then this little LIBOR snafu today didn’t cause the crisis – so what did cause the crisis? Is it that the banks and investors could no longer achieve any gains at any investment price or any beneficial interest rate? And even tho’ they tried to manipulate LIBOR to benefit some of their own trades, they still could not stay afloat because they were all doing it and all going down together. So what happened between 1980 and 2007 to make the system that had worked for 30 years suddenly collapse? My only guess is that capitalism itself finally failed catastrophically in 2007 due to the failure of its bedrock idea: competition. The system could no longer invest in growth because of the super productivity it had achieved, due to a confluence of cheap international labor and a relentless super-efficiency in industrialized countries. The system then had no other ideas, and collapsed. Karma. So the only question is, How do we organize ourselves now? Let’s start with financialization – make it an international felony with a minimum of 20 years. If all former financializers (i.e. all of Wall Street) come clean they can get off on the promise of at least 20 years of good behavior. No slip ups.

The cancer of the financial economy takes many years to grow but when the end is well nigh, it ends at the speed of light, consuming all.

econ says:

July 23, 2012 at 3:59 pm

“The cancer of the financial economy takes many years to grow but when the end is well nigh, it ends at the speed of light, consuming all.”

The financial equivalent of pancreatic carcinoma: “… may grow without any symptoms at first. This means pancreatic cancer is often advanced when it is first found.”

From the few friends who have checked out with this condition, the last stage is somewhat Hobbesian in that it is brutal, relentless, and terminal.

Interesting little tidbit. While working in mortgages at JPM Chase, shortly after Jamie came on board, ARMS, that were previously priced based on treasuries, switched over and were based on LIBOR. The reason given to the “worker bees” to relay to the consumer was…. LIBOR is more “stable”. The incredibly ethical small bank I now work for, still prices their ARMS by CMT. And from what I hear from my friends, most of the big financial institutions, use LIBOR and not treasuries. Anyone who doesn’t realize that this whole “situation” was a mass consipiracy by big banks, needs to have their heads examined.

U.S. Cities Get Fleeced in Libor Scandal

http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2012/07/23/US-Cities-Get-Fleeced-in-Libor-Scandal.aspx#page1

Libor: What Criminal Charges Are Likely?

http://www.cnbc.com/id/48288450

I’ll believe it when I see it some low level people is all we will probably see…

Obama’s Justice Department Rushes to the Rescue of LIBOR Criminals

http://www.blackagendareport.com/content/obamas-justice-department-rushes-rescue-libor-criminals

Oh geeze this is a bad idea the NYT has nationalizing the banks socializes the losses Ireland found that out the hard way instead BREAK THEM UP

Wall Street Is Too Big to Regulate

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/23/opinion/banks-that-are-too-big-to-regulate-should-be-nationalized.html?_r=2

Lady, very good points. Govt will not break up the bigs because the relationship is too symbiotic. It’s like asking them to chop off their right arm. They need an accomplice to fudging their deficits , humbly i.m.o.

Yesterday 07:43 AM

Incremental Risk Charge: An analysis: Going forward how much will the Libor scandal cost Barclays Bank and who will be chosen to lead its affairs.

Answer: See No.5 below.

In the aftermath of the Barclays Bank Libor scandal (financial Hiroshima) and their greed and subsequent cover up tactics, we studied the future impact on the bank and its franchise in the next 6-8 months using the ## Monte Carlo method and the capital asset pricing model. This has been developed using variable analysis on a common measure of the volatility of its ongoing business, i.e. its beta–which is determined using linear regression. These have been applied to the latest audited Barclays Bank balance sheet, their Libor rate rigging scenario and inferences drawn with 95% accuracy. The result highlights the following 5 points:

1. In the next 12 months, as its market standing and franchise has suffered, the Barclays Bank group will have to make a loan loss provision of USD 5.75 billion.

2. Their combined exposure (including paper transactions) is USD 1.35 trillion which they need to unwind at the earliest and reconcile their financials/book of accounts within 24 months. Overall loan losses to be written off could be around USD 3.5 billion and thus their paid up capital will be affected.

3. Their International trade, LC and LC confirmation business, correspondent banking business will reduce by about 40 % in the next 12 months as their price/rate quotation/covenants/IM will be seen with suspect.

4. As a result of (3) above, their overseas operations will reduce (some businesses will have to close down) by at least 30 % globally. This will open up a new avenue wherein, in the next 24 months, their overseas business will very likely be acquired by 2 Chinese and 1 Australian banking consortium.

5. The above points indicate that they will definitely need UK Government bailout well within a year. The UK government is already planning to nationalize the bank and make it a pure local British deposit taking bank going forward with an Australian as its head. Deposits/customers will come back to the bank only if the banks’ Investment Banking activities is completely spinoff. The Americans will make this happen.

## Methodology: I also used the Levy distribution – a continuous probability distribution which is unbounded below and above. The normal distribution is a special case of this with the parameter being one half of the variance. The Levy distribution, or Pareto Levy distribution, is increasingly popular in finance because it matches data well, and has suitable fat tails. The tail of the distribution decays like . Mean = and Variance = .

Who are you? That was incredible! Trully. Just giving cred where it’s due. Thanks for the post.

We could use some nice, national banks to lend money at reasonable rates to the real economy. Let the financial boys play their games with their own money, and keep ours separate and free of this silliness. We, the people, need a bank whose mandate is to support the economy, not enrich shareholders and CEO’s. So sure, nationalize them and put them to work for us for a change.