By Steve Keen, professor of economics & finance at the University of Western Sydney and author of Debunking Economics and the blog Debtwatch. Professor Keen has invented a simple way to build monetary models of the economy, and he’s raising funds via Kickstarter to pay programmers to develop he software, which he’s calling Minsky. He’s raised over $50,000 already, but as much as $1 million is needed to pay for 10,000 hours of programming time to fully develop the program. Please pledge support now at Minsky campaign: http://kck.st/XhKtdX.

Krugman describes himself as a “sorta-kinda New Keynesian”, and explains in his book End This Depression NOW! that New Keynesian macroeconomics evolved in reaction to the failure of the new classical approach to “explain the basic facts of recessions”.

His “sorta-kinda” qualification is because both New Keynesian and new classical models derived from applying assumptions about the behaviour of individuals and markets at the level of the macroeconomy, and he has a healthy scepticism about these assumptions:

I don’t really buy the assumptions about rationality and markets that are embedded in many modern theoretical models, my own included, and I often turn to Old Keynesian ideas, but I see the usefulness of such models as a way to think through some issues carefully – an attitude that is actually widely shared on the saltwater side of the great divide.

This is one aspect of Krugman that I genuinely applaud: the awareness that models aren’t reality. At best they are representations of reality, but some neoclassicals show an amazing capacity to believe that their models are reality – as in this piece by French economist Gilles Saint-Paul which the blog Unlearning Economics deservedly flogged recently – in a way that leads to truly delusional thinking about the real world.

Of course, we need models to think about the economy in the first instance, because it is such a complex entity. Even those who deride modelling in economics are using a model when they talk about the economy – it’s just a verbal (or even unarticulated) one, as opposed to an academic construct.

One might hope that experience and experimentation over time would weed out unrealistic models in economics, but that hasn’t happened. In many ways, the models that dominate economics today are less realistic than those which prevailed as much as seventy years ago.

Krugman alludes to this by his reference to “Old Keynesian ideas” above. In particular, he champions John Hicks’ IS-LM model as an explanation of our economic crisis today.

This model, first published in 1937, seeks to explain the relationship between interest rates on one hand and real output, in goods and services and money markets, on the other.

In his first paper on the model, Hicks proposed that the Great Depression was caused by what was later termed a “liquidity trap”. Hicks argued that it was possible for the economy to be in an equilibrium (a word I’ll be labouring in this post) in which there was involuntary unemployment.

(Why the word “involuntary”? Because the so-called ‘freshwater’, new classical economists that Krugman is accustomed to fighting to argue that all unemployment is voluntary: people look at the current wage, consider the loss of leisure they’d incur to have to work for it, and decide that not working gives them higher utility.)

To get down to the technical nuts and bolts, Hicks’ model had two intersecting curves. They were called the IS curve (representing Investment – Saving) and the LL curve (representing Luiquidity Preference–Money Supply; this was later relabelled LM). These were drawn on a diagram with the rate of interest (i) on the vertical axis and the level of income (I) on the horizontal. (Income was later labelled “Y” to get away from the sheer bloody confusion of multiple “I”s). And the point where the two lines intersected represented equilibrium in both markets.

I’ll delay explaining how the curves are derived until I get to Krugman’s use of the model; for now the important thing is the shape of the curves.

Figure 1: Hicks’ original IS-LL model, from page 153 of his 1937 paper Mr Keynes & the Classics (click to enlarge):

Hicks argued that the LM curve would be flat at low levels of the rate of interest, and steep at high levels of income (as shown in his figure 2). This was because, as he put it, “there is (1) some minimum below which the rate of interest is unlikely to go; and (though Mr Keynes does not stress this) there is (2) a maximum to the level of income which can possibly be financed with a given amount of money.”

Hicks then used this to divide the diagram into two regions, depending on where the IS curve intersected the LM.

If the intersection was in the section where LM was rising steeply, then an increase in demand – caused by, for example, a budget deficit – would mainly drive up the rate of interest, with very little impact on the level of income. This was the ‘classical’ region where what is today called ‘crowding out’ (when government borrowing reduces investment spending by crowding out private investment) would occur and where deficits only cause bad things like higher interest rates (and, in more elaborate models, inflation).

However if the IS curve intersected with LM in its flat region, then an increase in demand via a government deficit would drive the equilibrium income level higher, while having very little impact on the rate of interest. This was the region where Keynes’s arguments applied, said Hicks: that when the economy was depressed and income was very low, the government should stimulate demand by expansionary policy.

It was also where monetary policy was ineffective – as Hicks illustrated in his figure 2. Because there was already a minimum level for the rate of interest – which later economists christened “the zero lower bound” – then this bit of the curve couldn’t be shifted by increasing the amount of money. Only if the economy were in the ‘classical’ region, would increasing the supply of money move the LM curve further out – as shown by the dotted line in Hicks’ figure 2. Therefore monetary policy was effective when income was high, but ineffective when income was low (and unemployment was high).

On the other hand, in the region where the LM curve was flat, monetary policy was ineffective but fiscal policy – which could shift the IS curve – worked. Since this was what Keynes was advocating in The General Theory, Hicks concluded: “So the General Theory of Employment is the Economics of Depression”.

The IS-LM model took over the academic profession in part because it eliminated the apparent existential threat to neoclassical economics that appeared to exist elsewhere in Keynes’s work – as for example in these wonderfully confrontational lines from Keynes’s own summary of his message in the paper The General Theory of Employment in 1937. “I accuse the classical economic theory of being itself one of these pretty, polite techniques which tries to deal with the present by abstracting from the fact that we know very little about the future,” Keynes said.

Instead, there could be peaceful co-existence: neoclassicals owned the boom times, while Keynesians got the bad times. But just as with peaceful coexistence in the geopolitical sphere, at least one side didn’t really believe in it. Neoclassicals hoped for total domination, and in the battle to achieve it they were aided both by economic circumstances and by the nature of that other sphere of economics, microeconomics.

After WWII, the times appeared to be good all the time – certainly in comparison to The Great Depression, when unemployment hit 26 per cent (see figure 2) – so that neoclassicals got most of the airplay and Keynesians very little. Neoclassical theory also ruled the microeconomic roost, and from this fortress emerged a campaign to destroy Keynesian thought entirely.

Figure 2: US Unemployment rate. The U-6 measure today is comparable to the official measure in the 1930s

In what became known as the microfoundations debate, neoclassicals attacked the Keynesian part of the profession with the charge that Keynes “did not have good microfoundations” – that Keynesian results like an equilibrium with unemployment contradicted microeconomic theory. As Lucas emphasised in his 2003 speech to the History of Political Economy conference when he was President of the American Economic Association, a key target in this assault was Hicks’ IS-LM model.

Nobody was satisfied with IS-LM as the end of macroeconomic theorising. The idea was we were going to tie it together with microeconomics and that was the job of our generation.. (Lucas 2004, p. 20)

Now the bad times are back, and Krugman is trying resuscitate IS-LM. I argue that he should leave it dead—not for the reasons that the New Classicals killed it off (being inconsistent with Neoclassical microeconomics is a plus in my books) but because it’s a lousy model for what we’re experiencing right now. There’s no better way to show this than to outline how Krugman is trying to use it, and show that he gets it wrong.

Krugman’s Derivation

Krugman describes his derivation of IS-LM in two posts that feature as “essential reads” on his blog: “IS-LMentary” and “Liquidity preference, loanable funds, and Niall Ferguson (wonkish)” (Krugman 2009). He portrays IS-LM as “a way to reconcile two seemingly seemingly incompatible views about what determines interest rates”:

One view says that the interest rate is determined by the supply of and demand for savings – the “loanable funds” approach. The other says that the interest rate is determined by the tradeoff between bonds, which pay interest, and money, which doesn’t, but which you can use for transactions and therefore has special value due to its liquidity – the “liquidity preference” approach. (Krugman 2011)

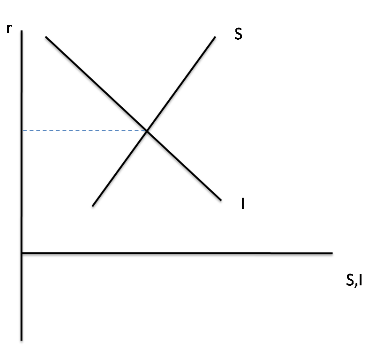

In his attack on Niall Ferguson, Krugman guesses that Ferguson has a simplistic view of the Loanable Funds model in isolation as the basis of his opposition to fiscal stimulus. That model shows the supply of saved money as increasing as the rate of interest rises, while the demand for borrowed money falls as the rate of interest rises. Where the two lines intersect, the demand for savings from firms equals the supply of savings from households (see Figure 3, from Krugman’s takedown of Niall Ferguson).

Figure 3: Step 1 in Krugman’s derivation of an IS curve

Krugman speculated that this vision, and this alone, explained why Ferguson thought “that fiscal expansion will actually be contractionary, because it will drive up interest rates”. But Krugman points out that this picture alone ignores the fact that both the investment demand for money (I) and the household supply of money (S) depend on the level of GDP: a higher level of GDP will enable a higher level of savings, and it will also be associated with a higher level of investment. So you need to know GDP as well to work out the interest rate in the market for Loanable Funds.

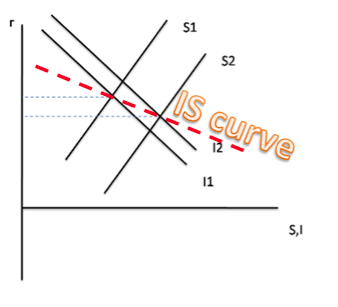

Both the S and the I lines will shift out as GDP rises—which one will shift more. Here is the first bit of “shifty” logic: to ensure that the IS curve slopes downwards, Krugman assumes that savings will rise more than investment does for a given increase in GDP:

Suppose GDP rises; some of this increase in income will be saved, pushing the savings schedule to the right. There may also be a rise in investment demand, but ordinarily we’d expect the savings rise to be larger, so that the interest rate falls.

Krugman concludes his derivation of the IS curve with a dynamic observation: that a fall in the interest rate (for some other reason—say an attempt by the Fed to stimulate the economy) can cause both savings supply and investment demand to expand:

Suppose that desired savings and desired investment spending are currently equal, and that something causes the interest rate to fall. Must it rise back to its original level? Not necessarily. An excess of desired investment over desired savings can lead to economic expansion, which drives up income. And since some of the rise in income will be saved – and assuming that investment demand doesn’t rise by as much – a sufficiently large rise in GDP can restore equality between desired savings and desired investment at the new interest rate.

Given that assumption, the intersection of I2 and S2—which represent investment demand and savings supply at a higher level of GDP than I1 and S1—is lower than the intersection for I1 and S1. If you join these equilibrium points up, you get Krugman’s downward-sloping IS curve (which I’ve added in to Figure 4 as a red dotted line)

Figure 4: Step 2 in Krugman’s derivation of an IS curve

Then there’s the LM curve. Krugman explains this as follows:

Meanwhile, people deciding how to allocate their wealth are making tradeoffs between money and bonds. There’s a downward-sloping demand for money – the higher the interest rate, the more people will skimp on liquidity in favor of higher returns. Suppose temporarily that the Fed holds the money supply fixed; in that case the interest rate must be such as to match that demand to the quantity of money. And the Fed can move the interest rate by changing the money supply: increase the supply of money and the interest rate must fall to induce people to hold a larger quantity.

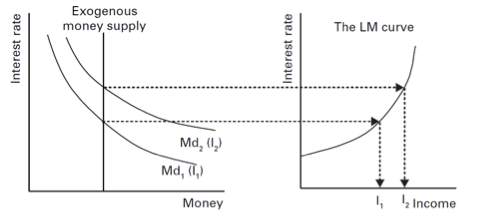

Krugman doesn’t provide a diagrammatic derivation of the LM curve, so I’ll provide mine from Debunking Economics (you can download the supplement with all the figures in the book from here; this Figure 5 below is Figure 61 on page 25 of the supplement). A key part step is the proposition that the Federal Reserve controls the supply of money, and that it can move it at will—so the money supply is an “exogenous” factor in the model since it is not controlled by the market. Therefore the money supply is shown as a fixed vertical line in the model: it’s impervious to both the rate of interest, and the level of income.

The demand for money however depends on both those things: a lower interest rate will increase the demand for money, since there’s less benefit in foregoing ready access to your money and buying bonds instead; a higher income will increase the demand for money, since there are more transactions taking place and you need more money on hand for them. The first factor is shown by having a downward-sloping demand for money curve for any given level of income; the second is shown by moving the demand curve out to the right as income rises.

Figure 5: Deriving the LM curve–Figure 61 in Debunking Economics

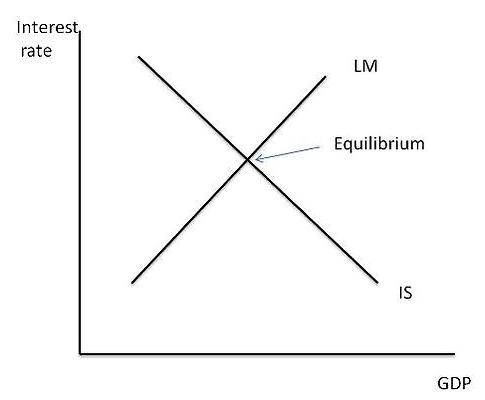

Equilibrium in the LM market thus depends on both the rate of interest and the level of GDP. When you plot these equilibrium points on a diagram with GDP on the horizontal axis and the rate of interest on the vertical, you get an upward-sloping LM curve—the second half of the overall IS-LM model.

Put the two curves together and the equilibrium of both—the point where the two curves cross—gives you the equilibrium interest rate and GDP for the economy. As Krugman puts it:

The point where the curves cross determines both GDP and the interest rate, and at that point both loanable funds and liquidity preference are valid.

Figure 6: The IS-LM model (from Krugman’s IS-LMentary)

Well Yada Yada. After all that, we’re staring at the economist’s favourite abstraction, a pair of intersecting lines. How does Krugman use them to explain the current crisis—and why is he wrong?

I’ll cover those topics in next week’s post.

References

Hicks, J. R. (1937). “Mr. Keynes and the “Classics”; A Suggested Interpretation.” Econometrica 5(2): 147-159.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. London, Macmillan.

Keynes, J. M. (1937). “The General Theory of Employment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 51(2): 209-223.

Krugman, P. (2009). “Liquidity preference, loanable funds, and Niall Ferguson (wonkish).” The Conscience of a Liberal http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/05/02/liquidity-preference-loanable-funds-and-niall-ferguson-wonkish/.

Krugman, P. (2011). “IS-LMentary.” The Conscience of a Liberal http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/09/is-lmentary/.

Krugman, P. (2012). End this Depression Now! New York, W.W. Norton.

Lucas, R. E., Jr. (2004). “Keynote Address to the 2003 HOPE Conference: My Keynesian Education.” History of Political Economy 36: 12-24.

Mr. Keen, I loved your book, but this post leaves me bewildered, perhaps because it is 4:07 and I only slept four hours out of the past twenty-four.

In today’s world, interest rates are determined by central bankers. Savers have a simple choice: risk or no risk. Those opting for no risk take the prevailing central bank determined rate. Those opting for risk reach for corporate bonds and stocks, or other financial assets, or even commodities or real estate. The idea of liquidity preference may be a shorthand way of expressing this, but it confuses the issue by suggesting that savers play some active role in determining the rate of interest. They don’t.

Investment is not carried on by savers. Investment is a business phenomonon driven primarily by perceived opportunity, and only secondarily by the rate of interest. When interest rates get high enough marginal projects are certainly choked off, but that isn’t going to happen again in my lifetime, and perhaps not in yours either.

I know this may not be entirely about IS-LM, but shouldn’t we spend our time talking about reality rather than a 75 year old abstract fantasy?

Well said.

The point of the post is that Krugman is wrong about ISLM. If the foremost economist of his generation is out there delivering bad information, he needs to be called out. Ignoring it will only make things worse.

Keen is just setting the scene for his attack on IS-LM. He’s getting his readers up to speed on Krugman’s take, so he can demolish it in the next installment.

I wish I could read this graphed stuff without my eyes glazing over. My brain just takes a nap. I understand Craazy below far more lucidly than Keen or Krugman. From reading his previous stuff, I do trust Steve Keen. I wish he could write to my level. And as far as “Minsky” goes, I’d like to know if this is his ‘all and everything’ approach to debt as it functions in the real economy. The model includes our debt to fossil fuel and combustion engines and the environment. That’s the snafu. The ultimate Minsky moment for us now. Just face the hubris here: think how difficult it would be to get out and push your two-ton SUV all over town. I wanna read that model, charts and all.

Just a couple of thoughts on all these good comments and the postings. The mainstream thought in the Democratic Party right now – I’ve seen it in Emails from party officials – is the celebration of Bill Clinton’s 1990’s combination of budget cuts and taxes increases which led to a surplus which led to Nirvanna at the end of the 1990’s: low unemployment, greater productivity and of course, that balanced budget. Talk about wild variables and the confusion between correlations and causation. Critics like Dean Baker, James Galbraith really have a feast slicing up what really happened. For just one example – about interest rates – Galbraith (in “The Predator State”) says that Greenspan raised the short term rates in 1994 hoping to head off the always just around the bend inflation, but by narrowing the “yield curve” between short and long term interest rates, he drove the speculative crowd into riskier ventures…whcih included the Dot.com bubble and later NASDAQ burst in the spring of 2000. Which also raises the question, based on Steve Keen’s posting, about the carry trade: the low “i” can lead to sure thing investing abroad in rewarding but not risky bond spreads…and the effect on US domestic GDP as a result? Well….

My own course experience in one year of economics at college was that I got Macro very well, and in micro, I just couldn’t buy all the forced assumptions that required you to play along…and if you’ve read your history of economic thought you know from the early theorists of classical economy how important those enormous assumptions are for what follows…from the labor theory of value (not defending it, just citing its history) which informed Smith, Ricardo, ballooned by Marx…to micro, where labor’s importance (and dignity) just about drops out of the equations…mirrored and echoed in dropping the issue of full employment in favor of inflation suppression…and still going on today by killing policy options to create full employment ala New Deal or Krugman, more indirect government spending…so you can argue, as Bil Greider has, that the Fed is the white knight today…but again despite being immersed in the history of the Great Depression, the Bernanke is remote and abstractly distant from beneficial labor policies…and L. Randall Wray and Marshall Auerback haven’t been able to even get a foot in opening the door wider.

So: the more micro, the greater the injustice?

Let me first thank those who are or may soon be debating me on this.

EconCXX wrote: circulating M1 is created with each draw out of a loan account.

Paul : Agreed. Money is created as debt. Money is also created against equity.

EconCXX wrote: It’s extinguished with each payment from a deposit account to a bank. The difference, the money destroyed in the process, represents interest and fees

Paul: That isn’t how I understand it. Interest and fees are bank income the bank gets to spend. When a borrower makes a mixed principal and interest payment, only the principal portion is extinguished. The remaining principal debt always equals the remaining principal created. The interest and fees portion is lent, spent or invested by the bank and become someone else’s credit (employees for instance).

EconCXX wrote: It’s not that the receiving bank doesn’t spend these receipts into the economy, as you point out.

Paul: If they spend them as you say, then they exist and have NOT been extinguished, and can (theoretically-mathematically) be earned by the borrower and paid again. How can you argue on one line that they are extinguished upon payment and then on the next say that this extinguished money is spent into the economy?

EconCXX wrote: It’s rather that they were debited twice, in the payer’s deposit account and in Bank B’s FedBank reserve Account. And augmented only once, in Bank A’s reserve account.

Paul: I don’t know why that matters. The ability of the bank to make a new loan has nothing to do with its Fed Bank Reserve account as has been revealed by Dr. Keen himself. My paper has references to that effect from the Fed and the Bank of England. Aggregate reserves will be provided as needed. There is no constraint except the interbank lending rate.

Aggregate reserves are unchanged in any case. The payer’s account is debited for the interest and fees and the bank’s spending of the interest and or fees gets deposited as someone else’s money elsewhere. Nothing is lost the way I see it.

The argument that the bank extinguishes its source of income has never made any sense to me and your argument contradicts itself in saying that the bank spends money it has already extinguished. How can that be?

And, lastly, if it were true, it would certainly compete with twice-lent money as the most important cause of money system instability. It would not refute it. Each would worsen the effects of the other.

Well over a year ago I challenged Dr. Keen to refute my simple theorem that explains why our money system is so unstable.

Here is my explanation in animated visual and text form. http://paulgrignon.netfirms.com/MoneyasDebt/twicelentanimated

Full analysis: http://paulgrignon.netfirms.com/MoneyasDebt/Analysis_of_Banking.html

Dr. Keen said he would refute me but never tried. I have challenged many economists and others to refute my theorem. Two people tried, one a physicist, and conceded that they could not refute it.

Millions have watched this explanation in my animated feature-length movie, Money as Debt II – Promises Unleashed, published in 2009

htmlhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LYZZWGl6vbA

I was invited to submit my theorem to the World Economics Association Conference on Econometrics currently online at:

http://peemconference2013.worldeconomicsassociation.org/?paper=proposed-new-metric-the-perpetual-debt-level

The conference has been extended to March 14

No one has refuted me there either. You could be the first!

The invitation is still open for Dr. Keen ESPECIALLY.

I took science in university. In science a theorem must be subjected to every possible effort to refute it. Only if refutation fails is the theorem considered valid.

I don’t want to continue advocating my theorem if it’s wrong.

It’s quite simple. REFUTE IT PLEASE!

This URL was cut off:

http://paulgrignon.netfirms.com/MoneyasDebt/twicelentanimated.html

working link to the movie segment

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LYZZWGl6vbA

>REFUTE IT PLEASE! @Paul Grignon

Easy enough, Paul. Interest and fees are extinguished when paid to a bank. You’ve just been looking for that extinguishment in the wrong place.

Simplest example: a bank charges you a $10/month fee to maintain a checking account. No ten dollar asset crosses through the teller window. Instead, $10 of the bank’s liability to you is extinguished. (If the bank gained $10 as you paid it, it would be $20 ahead: the $10 it obtained plus the $10 it no longer owes you.) Reserves remain unchanged, but $10 of aggregate M1, the circulating money of you and me and Apple and Exxon, has been destroyed.

Similarly, when you write a check from your account at bank B to pay your debt at bank A, that amount is debited from your checking account at Bank B, and extinguished from aggregate M1. Never again to circulate. But the interbank payment is cleared via Reserves, MB, with aggregate reserves remaining unchanged. One bank’s reserve loss is another’s gain.

So, circulating M1 is created with each draw out of a loan account. It’s extinguished with each payment from a deposit account to a bank. The difference, the money destroyed in the process, represents interest and fees. It’s not that the receiving bank doesn’t spend these receipts into the economy, as you point out. It’s rather that they were debited twice, in the payer’s deposit account and in Bank B’s FedBank reserve Account. And augmented only once, in Bank A’s reserve account.

When you consider where we are now, with $35/item overdraft fees, 3%/transaction merchant fees, lifetime compounding debt bondage, you can see why infinite QE is all that keeps the entire system from collapsing in unpayable and uncollectible compound debt.

EconCCX claims to have refuted my theorem by advancing an argument that further SUPPORTS IT.

The twice-lent money dynamic is completely independent of whether fees or interest is charged and EconCCX didn’t even mention it much less refute it.

1. Principal is created as debt 1: borrower owes it TO a bank

2. The same Principal is deposited as debt 2: a bank owes it TO a depositor

3. There is no other source of new money other than government bond issues.

How can debt 1 get paid if the depositor doesn’t spend it on time for the borrower to earn it on time to meet the borrower’s loan schedule?

Paul, you’re discussing the problem of compound interest leading to, basically, one man owning everything and everyone else being in debt to him.

There are several ways around this:

(1) default, bankruptcy, and forgiven debt, which are integral parts of our legal system, cancel out the (otherwise) ever-increasing interest. (Mild general inflation handles the remaining effect of the interest.)

(2) progressive taxation takes the interest accumulating in the hands of a few and redistributes it, by law, to everyone else, effectively neutralizing it. (Mild general inflation handles the remaining effect of the interest.)

(3) debt monetization — seignorage, printing money — eliminates interest “owed” by the government. (Mild general inflation handles the remaining effect of the interest.)

Any of the three can work to stabilize the system. Does that answer your question? If you don’t have one of the three then you’re right, the system is inherently unstable.

Paul, for what it’s worth, the other solution, which happened at the end of the Roman empire, is to replace “debts” with indentured servitude, serfdom, and slavery. This ends the capitalist system in favor of feudalism, so this really confirms your view that instability is inherent in capitalism.

The progressive taxation / easy bankruptcy / money-printing / inflation combination, however, stabilizes capitalism quite nicely.

Nathanael, compound interest is one form of twice-lent money.

P is less than P + ∞.

The other is multiple debts of the same principal in an interest-free environment. P is less than n P where n is greater than 1 and n = 2 by the design of the banking system itself.

My proof assumes that all interest is recycled as spending and is NOT a factor at all in the instability that twice-lent principal causes.

So NO I am not talking about” the problem of compound interest leading to, basically, one man owning everything and everyone else being in debt to him.”

I am talking about instability caused by multiple debts of the same Principal regardless of whether interest or fees are charged.

Paul, I followed your link, and got to this claim:

So I’ve indeed challenged your theorem at its foundations. You’re claiming that interest and fees recycle, thus that money at interest is destroyed no faster than money sans interest. Where in fact it’s the interest and fees in excess of the loan that extinguish the medium of exchange, requiring ever new and compounding indebtedness, under our present regime of multi-tier money, to service prior debt. You’re denying a mathematical problem; I’m identifying it.

BTW, I’m on your mailing list, own all three of your DVDs, and greatly appreciate your work.

My reply went to the wrong article.

First one ABOVE the beginning of this thread.

Show me on this bank statement where the interest and fees are extinguished.

http://www.marketwatch.com/investing/stock/bac/financials

I don’t see anything that contradicts my interpretation.

Anyone else find the animations and the liberal use of bolded text distracting when trying to get to grips with the claimed issue?

I am at a loss if you mean that when principal is extinguished the payment used to extinguish it goes up in smoke or not.

I could have sworn Keen has taken care of this issue by putting repayments of principal into the banks vault, allowing the bank to spend it back into the market via wages, goods and services needed for the daily operations of the bank.

Show me on this bank statement where the interest and fees are extinguished. @Paul Grignon

Greetings, Paul. Sorry to have been scarce over the weekend.

None of the balance sheet entries you’ve linked to are aggregate measures of the money supply.

Here’s M1 defined in the US.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M1NS

When a $35 fee is removed from a depositor’s checking account, there’s no corresponding asset (such as a coin, note or reserve balance) transferred to bank ownership. Instead, a liability is extinguished. The bank owed the depositor an amount; now it owes him that much less.

You see that the M1 component of the money supply includes demand deposits. Thus aggregate M1 has been decreased by the $35 fee. Can you point to any measure of the money supply that is increased by $35 in the process?

Now, bank capital or net worth certainly increases; that’s difference between the value of a bank’s assets and its liabilities. That’s a net value that includes all sorts of nonmonetary assets.

http://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bank-capital.asp

But the bank’s liability to the depositor, a component of aggregate M1, has been extinguished. Please see if you can demonstrate an offsetting increase in some defined component of the money supply.

If you can’t, then money beyond loan principal has been extinguished by this payment to the bank.

Digi Owl: Please read my paper at the WEA for the less exhaustive plain text and professionally referenced version.

http://peemconference2013.worldeconomicsassociation.org/?paper=proposed-new-metric-the-perpetual-debt-level

As for both DigiOwl and EconCXX’ claims:

1. DigiOwl: I submitted as evidence a link to an actual bank income statement for Bank of America Corp.

http://www.marketwatch.com/investing/stock/bac/financials

NOTE: there is no mention of PRINCIPAL at all, much less any income from it. That should be a clue that Principal is extinguished when paid. As I describe here:

http://paulgrignon.netfirms.com/MoneyasDebt/How_Principal_is_Extinguished.html

2. EconCXX: Lines 1-14 of Bank of America’s statement clearly show that interest and fees are booked as income subject to tax and SPENT on (QUOTE in order of significance) Loan Loss Provision, Labor & Related Expense, Equipment Expense.

The loan loss provision is money “set aside” in anticipation of non-payment ie. non-extinguishment of money in circulation. This money will be extinguished if loan money is not.

The other expenses are clearly SPENT back into circulation. The net income of the bank is subject to INCOME TAX so that some of it will be transferred to the government. The rest is distributed as dividends.

You want to argue with the bank’s accounting and claim the bank extinguished its own income so that it had no money with which to pay for employees equipment, and dividends? I don’t see any proof in that bank statement. If horses’s mouth evidence doesn’t do it for you what would?

@Paul Grignon You want to argue with the bank’s accounting and claim the bank extinguished its own income so that it had no money with which to pay for employees equipment, and dividends? I don’t see any proof in that bank statement. If horses’s mouth evidence doesn’t do it for you what would?

No, because I already volunteered that the bank that gains these interests and fees from payments made through another bank is free to spend that money. Because that’s not where the extinguishment takes place. It takes place at the demand deposit level of the “other” bank, the bank against which the fee check was written. That bank cancels some of the checkwriter’s M1, while also conveying Reserves, Central Bank Money, to the bank collecting the fee. Aggregate reserves thus remain unchanged, but aggregate M1 has been diminished. You can’t point to the fee-collecting bank’s income without also recognizing both the fee-payer’s loss of checkbook money, and her bank’s loss of Reserves.

But let’s start with the original example, where these are the same bank. Please, it’s much easier to understand this one first. Do you believe that when the bank charges a $35 overdraft fee to your account, that aggregate M1, which includes demand deposits, is diminished in that amount? Or do you believe that the fee simultaneously becomes an asset of the bank, leaving money aggregates unchanged?

Remember, the checking account represents the bank’s debt to you. It’s not a bag of coins or a box of bills the bank is holding for you. To extinguish a liability while simultaneously gaining an asset would be a double collection.

If you see the loss of $35 of M1, can you see the extinguishment of that much of the community’s medium of exchange? Coins are positive money, assets to whoever owns them. Debts can be cancelled by mutual agreement between creditor and debtor. Checkable bank debt is no exception. The depositor agreed with the bank, however reluctantly, that if she overdrafted her account, $35 of the bank’s debt to her would be cancelled. The checkable bank debt extinguished is checkbook money, a component of the money supply. The community’s medium of exchange. Money as Debt. Your own gifted concept.

EconCXX wrote: “Because that’s not where the extinguishment takes place. It takes place at the demand deposit level of the “other” bank, the bank against which the fee check was written.”

Why is another bank involved? When did the payer have to write a check on another bank? Didn’t you just say the fee is just a reduction in the bank’s debt to its account holder? When my bank charges me fees they are deducted on the month-end statement. I don’t have to pay them by writing a check on another bank.

@ Paul Grignon, the model you’ve described here:

http://paulgrignon.netfirms.com/MoneyasDebt/How_Principal_is_Extinguished.html

cannot be accurate. If a borrower writes payment check for $1000 against another bank, all of that money goes to an account belonging to the lending bank. Most likely the lending bank’s reserve account at FedBank. None of that money is extinguished. Neither principal nor interest. All of it can be drawn upon. Naturally, some of it is allocated to replenish the reserves that were surrendered when the borrower wrote checks against the bank, but that’s not extinguishment. What’s extinguished at the lending bank is a portion of the bank’s claim of action against the borrower.

No, the extinguishment of money takes place in the deposit accounts of the bank against which the check was written. Demand deposits (M1) are reduced by the full amount of the check. To clear the check, reserves are conveyed interbank, and thus unchanged in the aggregate. Exactly the same as when I write a check to you…except that there isn’t that third transaction where your bank owes you the sum of the check I wrote:

Demand deposits (M1) augmented.@ Paul Grignon Why is another bank involved? When did the payer have to write a check on another bank? Didn’t you just say the fee is just a reduction in the bank’s debt to its account holder? When my bank charges me fees they are deducted on the month-end statement. I don’t have to pay them by writing a check on another bank.

I offered both examples. The first paragraph described payments via a second bank, where the primary bank gains an asset. Subsequent paragraphs describe a single bank transaction involving the cancellation of the bank’s own liability.

Of course we make payments all the time from our deposit banks to our credit card issuing bank or car loan bank. Not ordinarily for checking account fees…but if you’ve truly overdrafted your account as per the example, you’ll need to convey those funds from an outside source. ☺

Dunno how banks do it regarding company credit, but in terms of private credit the principle is payed back over time along with interest payments, meaning that the principle may well be hiding out in the “interest and fees on loans” line.

EconCCX wrote:”If a borrower writes a payment check for $1000 against another bank, all of that money goes to an account belonging to the lending bank. Most likely the lending bank’s reserve account at FedBank. None of that money is extinguished. Neither principal nor interest. All of it can be drawn upon.”

Paul: The “other” bank’s liability to its depositor is reduced by $1000 and $1000 of its Fed Reserve is transferred to the account of the lending bank. The lending bank’s Reserve account is credited (asset) with $1000. The borrower’s debt to the lending bank (bank asset) is reduced by $200. Thus the lending bank’s assets are reduced by $200, the amount of the Principal payment.

$800 in interest earnings (assets) are available to offset the lending bank’s liabilities. That is, $800 is available to the lending bank as income to spend, lend or invest.

Only the $200 of Principal was extinguished.

I find myself wondering if the devil is in how the principal is mentally defined. Banking rules and operations still pretty much act as if money is still physical. As such, the principal is seen as coming out of the banks money “hoard”.

And so when payed back, listing said principal as income, never mind profit, would be mentally wrong for the accountants. After all, it is only returning what was the lender’s in the first place.

End result is that it will seem as if the principal simply vanishes, while actually the bank has earned money it never had because modern credit is simply a ledger entry.

And so it is a sleight of hand of epic proportions.

DigiOwl

Money is created as debt and extinguished by repayment.

Bank assets are performing loans. When the loan is repaid the asset is reduced to ZERO.

@Paul Grignon When the loan is repaid the asset is reduced to ZERO.

Given that the asset also grows with the passage of time, in what sense is $200 of the reserve extinguished as it is applied, in the bank’s books, to principal? You’re saying that only “$800 is available to the lending bank as income to spend, lend or invest.” I’d think the entire $1000 is. It’s all in the lending bank’s reserve account at FedBank. Nowise extinguished. Certainly hope that’s the case, because those reserves were drawn down when the borrower wrote checks or swiped a card against the loan account.

Reserves are interbank settlement money, extinguished only by FedBank. The extinguishment of bank credit money takes place at the deposit level. As I’ve been saying. The borrower writes a payment check to the bank. His deposit, and aggregate deposits are drawn down. No new deposit is created, as there would be if the payment were to a merchant. And extinguishment at the deposit level includes principal, interest and fees, requiring the community to borrow further for its means of repayment.

EconCCX wrote: “And extinguishment at the deposit level includes principal, interest and fees, requiring the community to borrow further for its means of repayment.”

Paul: The $1000 balance at the Fed is spendable by the bank as deposit money. You have NOT mentioned bank spending. Why wouldn’t the bank spend its income? It has to spend some or all of it as wages, operating costs and dividends as I proved with an actual bank statement.

Performing loans = Bank assets.

The performing loan has been reduced by $200, the amount of the Principal. Thus bank assets have been reduced by $200. M1 has been reduced by $200.

The bank spends the full $1000 and increases M1 by a net $800, the amount of the interest.

You can continue to ignore bank spending if you like. I provided an actual bank statement to prove my case.

EconCCX wrote: “Reserves are interbank settlement money, extinguished only by FedBank. The extinguishment of bank credit money takes place at the deposit level.”

Paul: Banks settle deposit money debts with interbank settlement money, thus X amount of FedBank money allows banks to spend X amount of deposit money. The bank uses its Fedbank reserves to issue itself spending money. You see a problem here?

@ Paul Grignon

PG: Performing loans = Bank assets. The performing loan has been reduced by $200, the amount of the Principal. Thus bank assets have been reduced by $200. M1 has been reduced by $200.

The definition of M1 was cited upthread. Currency, demand deposits, travelers checks. Commercial banks’ liabilities are in there, not their assets (the liabilities of other banks excepted, and these are still bank debt.) M1 can’t be both, and I hope you’ll acknowledge the contradiction.

PG: The bank spends the full $1000 and increases M1 by a net $800, the amount of the interest. You can continue to ignore bank spending if you like.

We’re agreeing that the bank has the capability of spending or lending the full $1000 at some point. Which means your model doesn’t show the extinguishment of money, only the repayment/extinguishment of a loan. It’s imperative to show the extinguishment of deposit money as well. Otherwise, each mortgage and each swipe of a credit card permanently increases M1. An impossible outcome.

Again, the extinguishment of checkbook/deposit money (bank debt, a component of M1) takes place with each payment to a bank. As distinguished from a payment to a merchant, which does not extinguish but merely reapportions commercial bank debt. Unfortunately, the extinguishment includes P+I+F, leaving the community ever deeper in debt through the very engineering of its money system.

MAD IV is going to be epic. Hope you’ll allow me to contribute to its development when the time comes.

Econ CCX: “Commercial banks’ liabilities are in there, not their assets (the liabilities of other banks excepted, and these are still bank debt.) M1 can’t be both, and I hope you’ll acknowledge the contradiction.

There’s no contradiction at all!

Performing loan = bank asset

Bank asset = bank liability

Bank liability = M1

Where is the contradiction?

EconCCX: “MAD IV is going to be epic.”

There will never be a MAD 4. MAD 3 is my SOLUTION to the twice-lent money problem you have yet to address.

@ Paul Grignon

PG: Bank asset = bank liability

If that were the case, then the Cypriot financial crisis would appear to be seriously overblown. No such luck. The accounting equation in general ledger is:

Assets = Liabilities + (Shareholders' or Owners' equity)or, rewritten:

Assets - Liabilities = (Shareholders' or Owners' Equity)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_ledger

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accounting_equation

And only a fraction of a banks’ assets and liabilities are money. The bank’s owners absolutely gain equity as bank liabilities are extinguished, but that equity isn’t a circulating medium of exchange, nor does it add to any measure of money.

EconCCX wrote: “The bank’s owners absolutely gain equity as bank liabilities are extinguished, but that equity isn’t a circulating medium of exchange, nor does it add to any measure of money.”

Paul: But bank liabilities ARE spent, circulate and replace the circulating medium of exchange, and I provided a real bank year-end statement to prove it. This argument is going nowhere and you have not even addressed the twice-lent money argument, where you might find the real and much simpler reason that debts outstrip the money in existence to pay them.

@ Paul Grignon

PG: This argument is going nowhere

I believe that you’re determined to get this right. The punt that “bank assets = bank liabilities” and acknowledgement that a bank that receives $1000 through reserve clearance is free to lend or spend all of it, should be sufficient to demonstrate that your model doesn’t extinguish credit money.

Good luck with it anyway. And thanks for this conversation and all your vital work shedding light on our money system.

This might put your mind at ease on one subject… Carbon dioxide is a plant nutrient. Plant are nutrients to us and provide oxigen too. Carbon dioxied is the epitamy of green. People put it green houses to increase growth and growth rate

And too much of a good thing is a bad thing.

Venus has an atmosphere very high in carbon dioxide. Venus’s greenhouse effect causes surface temperatures of 740 K (467 °C, 872 °F),

It is speculated that the atmosphere of Venus up to around 4 billion years ago was more like that of the Earth with liquid water on the surface. A runaway greenhouse effect may have been caused by the evaporation of the surface water and subsequent rise of the levels of other greenhouse gases.[7][8]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atmosphere_of_Venus

The Earth faces a similar future thanks to us.

whoa, this is head-spinning stuff. I took economics in college. Didn’t understand it then and don’t now — one reason was because I didn’t go to class and did bong hits instead. None of this makes any sense at all to me, even now when the head is reasonably clear at 6:30 a.m. There are too many variables flying around that mutually depend on each other. If you try to isolate one to see the others move, you jump instantly into an artificiality that makes the entire enterprise an arid abstraction. I don’t believe it illuminates. Seems more like a language that’s missing words for “snow, tree, ice and clouds” — and you’re in Siberia trying to describe the world. There’s only so much you can say with “plants, animals, cold and hot”. Then somebody comes up with a “hot-warm-cold” curve and somebody comes up with an “ant-rabbit-wolly mammoth” curve and they intersect at “warm-rabbit” and you say “that’s not where we are”. OK. I trust Professor Keen more than most economists. I know this stuff isn’t easy. It may be it’s just over my head, so I’m reduced to making up my own version. I’ve concluded it’s 16 equations and 19 unknowns and you can solve for whatever you want, depending on nature, capital and imagination. Labor is a constant, but cooperation is 4-dimensional wave function. Where they intersect is a 3-dimensional arc moving in time. It’s hard to do the math. I came to the conclusion that cooperation creates money, not vice versa. This is an epistimological realization.

‘I didn’t go to class and did bong hits instead. None of this makes any sense at all to me.’

You just didn’t do enough of them bong hits. When you see the white light, it all becomes pellucidly clear.

There’s still time, C-man. ;-)

On Mongo we realized our economists were both very weird and not that smart, so your Emperor decreed that we limit our economic variables (also called “degrees of freedom” in the “hard” sciences) to equal the number of economic equations we have. Your Emperor can then input numbers in his spreadsheet and the Mongo economy is adjusted accordingly. “Stack overflow” means someone is headed for Mongo Commons, but then the spreadsheet works out ok afterwards.

You Earthlings are hopelessly deluded with this LS-IM model. If you are intent on finding where curves intersect, first you need to get the right curves. Warm-rabbit is a good start, but your Emperor believes this intersection still misses the mark.

May I suggest the Ben-Mario-Abe-PBoC Cyclical Liquidity Provider curve, the Saver – Bank Intermediation – Capital Investment Job Creator curve, and finally the Labor – Consumption – Sectorial Balancer – Business Cycle Curve.

At first blush one may think these could be plotted in 3D space, but when one realizes Labor – Consumption – Sectorial Balancer – Business Cycle Curve are not necessarily the same people, and depending on where you look on the Ben-Mario-Abe-PBoC Cyclical Liquidity Provider curve, they may be geographically scattered across your entire planet. For instance, a Ben Job Creator may be in the fourth dimension as far as Ben knows, a Mario Consumer is probably broke, a PBoC Labor is probably broke too, and we have no data whatsoever about the Abe data point. This speaks to the need for at least four dimensions.

On Mongo we sent all bankers to Mongo Commons, so we don’t have debt and everyone is on paygo in photon credits that expire in one year. This makes the model here on Mongo so simple even a Emperor can do it. But since you insist on having debt on your planet all these curves need a singularity when a debt limit is reached. If it were me, I would also include an audio panic alarm that goes off when any curves hit this limit.

So try that, if you must, but it seems like a waste of time to me.

“There are too many variables flying around that mutually depend on each other. If you try to isolate one to see the others move, you jump instantly into an artificiality that makes the entire enterprise an arid abstraction.” ~craazyman

When I pointed this out in my econometrics course (that interdependence among variables on the right side of the equation would seem to undercut the validity of the analysis) I was told that I was “jumping ahead” and that those issues would be addressed in graduate courses. I have a strange feeling that they’re probably not addressed, seeing as how I practically never see anyone discussing the issue…well apart from the occassional craazyman.

Yes, those first two graphs bring back some bad memories. In my case, uncorrected vision is the excuse for not learning anything. Also, being kind of dense helps. This is not to be confused with receiving a poor grade. It is amazing how much you can fail to take in and do just fine. And this was before the days of big time grade inflation.

I took Economics as a first term freshman. There were two of us, and the other guy was the scion of a family which owned most of West Virginia. On the first day, the tweedy pipe smoking professor told us two things: first, in this course, you will not learn how to make a million dollars (back then, this was a lot) in the stock market; second, I want no first term freshmen in my class. If there are any, come up and see me afterward.

We trooped up to his desk on what was probably my second day of college. Professor Tweedy began discouraging us. Scion piped up that he was well versed in economic theory and would prefer to stay. I said that I was familiar with Ricardo, Malthus, Keynes and Veblen, and would prefer to stay too. I didn’t tell him that my only background was a speed read of Robert Heilbruner’s The Worldly Philosophers.

The class proved incomprehensible. My notebook was filled with things like ‘sheer nonsense’, ‘absurd assumptions’, ‘who believes this stuff?’

Because I wanted to make money without working, I continued in economics, graduated cum laude, realized I had learned nothing of value, and went to law school, where I experienced the same thing. Fortunately, tuition was reasonable in those days. and it was common knowledge that college (and law school) didn’t teach anything of value, so I shrugged the whole experience off and got a job in a law firm which quickly proved to be a small crowd of poseurs and crooks. They made buckets of money and paid associates very well.

Ah, the good old days. I doubt they will ever come back, but they really did exist 40-50 years ago.

0011 = licensed to steal.

The good ole days are still around. It’s just that the license is more expensive. ;)

And they’ve taken away a good many chairs, and the things the bright students are required to do to keep one are considerably more repulsive, and even more stressful and time consuming, and the stealing is levied against the poor as opposed to the rich (which feels worse, somehow), and I don’t think the players still have as much fun, or believe even they have a future, but of course I could be wrong.

Hmm.. do you think the professor was impressed with the Veblen? Seems a bit gratuitous. (That’s a joke)

Glad things worked out for you.

Steve Keen quotes Kurgman:

This proposition is eminently testable. Go to FRED; download series GDPC1 (quarterly real GDP) and GS1 (monthly 1-yr T-note rate). Extract quarterly values from series GS1 (months 1, 4, 7, 10). Calculate first differences of each series, expressed as percentages … (current obs – previous obs) / previous obs.

Now apply CORREL function to the two derived series from July 1953 to Jan. 2013. Result: +0.29. Meaning: U.S. interest rates historically have moved UP during economic expansions, as anyone with even a cursory knowledge of the business cycle already knows.

Kurgman’s hokey 19th century narrative arguments just ain’t gonna cut it when every humble worker’s hovel has a computer and access to free data.

Kurgman: PWNed by Steve Keen! (And Steve hasn’t even begun administering the heavy flogging yet.)

Reality is wrong. Not the theory. :)

Another explanation is the widespread belief that emerged in the 18th century that it is possible to change reality so that it conforms to theory.

Krugman is assuming no central bank, right?

Paul Krugman Files Chapter 13 Bankruptcy

(Needs double sourcing, just to make sure)

http://www.24hgold.com/english/news-gold-silver-paul-krugman-files-chapter-13-bankruptcy.aspx?article=4272550092G10020&redirect=false&contributor=The+Prudent+Investor

Paul Krugman Files Chapter 13 Bankruptcy

by The Prudent Investor

Published : March 08th, 2013

Paul Krugman, the king of Keynesianism and a strong supporter of the delusion that you can print your way out of debt, faces depression at his very own doors.

According to this report in Austria’s Format online mag, Krugman owes $7.35 million while assets to his name came in at a very meager $33,000. This will allow the economist and New York Times blogger to get a feel of how the majority of Americans go about their dreadful lives without any savings and a social system that will only shed pennies to him.

………

I still need to read Steve Keen’s article.

Needless to say, if the above article is correct…Steve Keen certainly knows best.

marvelous, the hangover continues

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/03/links-3713.html#comment-1125384

Thanks.

i wasn’t beyond the ‘whiplash’ the first time i read the article but i didn’t think you wanted to see the posting-wrath to follows (my apology, i should’ve added a smile to my post)

Editing:

Needless to say, if the above article about Paul Krugman is correct, then Steve Keen certainly knows best.

99% sure that is false; a brief search doesn’t show that turning up from any reliable sources.

It is a fake story. Someone trying to parody how Krugman proposes to fix the economy.

Nothing to see here.

Krugman on anything but New Trade Theory or Economic Geography is like Rain Man on Roulette.

Recessions were created by and inacted by the 1% to gain more money and power. The 1%, better than anyone else, understands that the best time to buy is at the lowest price. Even Warren Buffet says that the best time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets.

I’m asking strictly as a layman, inept at math beyond the times tables, but isn’t there a point at which a particular model or series so pervades a mathematical perception of reality that incorporates significant elements of, say, price history, that the model itself becomes innate to the reality under investigation? It always takes two to tango: the phenomenon observed and the point from which it is observed. From that stage going forward, just as compound interest builds upon itself, interest on interest, don’t certain models, as it were, compound upon themselves? I always thought this was true of Black-Scholes: that the formulation became so widely used that it became – as it were – part of the option being valued.

social sciences (and economics is one such, at least when considering individuals or small social groups) do indeed have a problem with their actions (or inactions) tainting the phenomena they try to describe the behavior of.

Thanks for posting this by Steve Keen.

He is one of a handful of brave dissident economists mounting an assault upon the Alice in Wonderland fortress of mainstream economics.

My takeaway from this post is this: classical economic theory and its begets are 90% fiction and 10% reality, peppered with just enough reality to make them verisimilar. Their intention was never descriptive, but prescriptive: to portray an arbitrary and predetermined economic and social order as being “The Nature of Things.” “The Nature of Things” thus replaces “The Will of God” in the emerging capitalist order as an instrument of social control, and getting the underlcasses to accept this new cosmos was key for the 16th- and 17th-century bourgeoisie to solidify its domination, as C.R. Boxer explains here:

It is most unfortunate that all this highly esoteric matematical language is necessary to breach the bastions of bourgeosie fiction, but it seems to me the battle is unwinnable without it.

I read the whole article through trying very, very hard to understand those charts. So, from Mexico, what you have said seems to describe all that I learned from the article. I just hope that Krugman understands it better than I.

Well done Steve! You’ve seen Fadhel Kaboub’s piece on the subject…?!

Freshwater … saltwater … oily water, HEY! That’s what we run the economy on, today more water than oil, tomorrow more water still (more polluted water as well).

In the long run we’re all dead, right?

What Krugman and the rest don’t understand is the monetary economy doesn’t recycle funds, ‘velocity’ is overstated, banks don’t lend reserves, etc. In the credit money system there is always new ‘money’ being loaned into existence, it is always unsecured.

The evidence of exogenous money can be seen in the rising tide of complaints by some watery economists about the Fed ‘printing money’, which it doesn’t. All central bank lending is secured (or the central bank vanishes, ‘Poof’, into instant insolvency).

Credit is either secured or unsecured, all new money is unsecured (or secured by empty gestures, a bit of wealth re-pledged as collateral multiple times). Unsecured credit is the source of our precious ‘growth’ (and inflation). The IS-LM does not work, the monetary economy is not a closed cycle. As long as there are willing borrowers there is always more money.

The progress narrative/growth myth and evidence of resource waste/capital destruction is collateral enough for lenders. This is why the world’s stock markets are making new highs even when the populations teeter at the edge of the economic abyss. There are few savings/investments to recycle, just the banking system lending into its captive markets, making unsecured loans.

Oh stupid humans, we shovel our capital into the furnace so that we might become wealthy … Joni Mitchell was right, we don’t know we’ve got ’til it’s gone.

Does anyone else find it amusing that the title of this post is “Krugman doesn’t understand IS/LM” and it ends with the sentences:

“How does Krugman use them to explain the current crisis—and why is he wrong? I’ll cover those topics in next week’s post.”

lol?

Keen is in a hurry to be the figurehead for the New Wrong Economic Program. Would Australian economics be no water economics with the current drought?

Just another example of “lets you and him fight it out.” After all, Krugman is the one who needs to be squashed like a bug, right, not the Chicago mob or the Austrians and their neo-Thetan system of angry unicorn based economic reality. Krugman must be punished for being an establishment economist who expresses sympathy for the bums of the 47 percent. Fighting Mankiw would be too hard, or Holtz-Eakin, or Sachs, or Fat Larry.

On the other hand, Krugman might learn something (and be amenable to learning something) from the challenge, and may have a progressive change of mind on the topic.

In navigation there’s an old saying that “the map is not the terrain”, it’s a “similitude” of what we believe is the terrain. We oscillate between “I’ll believe it when I see it” and “I’ll see it when I believe it”. Even with the best map, if we don’t know where we are, it doesn’t matter where we’re going. Similarly, as the old saying goes, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any map will get you there”.

As a self-directed student, I very much appreciate Steve Keen, Michael Hudson and NC for helping me navigate through the quandary.

Reading this highly theoretical material reminded me of some of the truly useless turgid textbooks I waded through during an MBA course.

After achieving a cognitive state described as total abject boredom while reading this article, I began to reflect upon a book that really did grab my attention, “The Shadow World” by Andrew Feinstein. http://tinyurl.com/bbvmw7l

Feinstein describes the nature of business and economics todaay. He cited the example of central Africa. A plane flies in loaded with AK-47s, RPGs and other small arms and lands in Burundi or Rwanda where there is a back haul available of coltan which has been mined in the DR Congo by exploited and near-slave labor. This cargo then is sheep-dipped and sent on to the world’s manufacturers of smart phones and other high tech toys. The guns are forwarded back into DR Congo where in the past decade about 3 million people have been killed, raped or dislocated by the corporate world’s machinations.

This economics makes sense to me. Or, rather, it is understandable in how it works and what are the consequences.

What Steve Keen writes is childish foreplay for the reality of rape-and-pillage capitalism today.

Whenever economists use the word “equilibrium”, it always sounds to me like “the place where we happen to be at the moment”. What makes this point stable in any sense?

Lets just say that mainstream economics are still in the pre-chaos theory world. Keen is trying to change that with his Minsky software, a specially designed dynamic modelling program for economics.

Keen’s book Debunking Economics (http://amzn.to/TcDpQU) is an attack on the whole edifice of neoclassical economics, elements of which he is describing in this post in preparation for taking it down in the next one. If I read his book correctly he doesn’t think it makes much sense either. Perhaps judgment should be withheld until then?

A little bottle labelled ‘Drink Me’.

Prof. Keen is one of those who predicted the 2008 finacial crisis. Here is his take on the cause of the crisis:

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Global_Economy/GECON-04-080313.html

I suppose the operative idea here is that you have to show that you understand an economist’s BS in order to effectively debunk it. I disagree. I don’t need to show expertise in the intricacies of fluxes and humors to debunk them as a basis of a pathology of diseases.

The argument is strewn with stated assumptions, like equilibria, or unstated ones, like rational interchangeable self-interested actors which simply don’t exist in reality.

But then there are all the concepts that are left out. Wealth inequality blows away the myth of the interchangeable rational actor right there. Many, indeed most people, either don’t have appreciable amounts of money or are using what they do have to pay down debt. It is only the 1% that has the luxury of choosing between investment and saving. The rich in fact do invest but their investment choices are either those that create no new jobs or destroy ones that already exist. Then too there is the criminality of kleptocracy which neither Krugman nor Keen is likely to touch upon.

I mean I already know that neoclassical economics is based on a series of false premises. I know too that Krugman has no real sense of concepts like money, debt, banking, let alone wealth inequality and kleptocracy. So this is going to be a GIGO process both in the general and in the particular. Whatever Keen does is not going to change any neoclassical minds, or Krugman’s. So why bother?

“So why bother?”, that’s a good question.

I am a big believer in Dr Keen’s work, but I do have trouble sorting out what neo-classical economists think versus what he thinks. Keen is clear that his purpose is to show how the neo’s logic is wrong, within their own model. But I always have Hugh’s question in mind. Really, why bother. Why not just say no, the neo’s are wrong starting at point A (for example, people are rational agents), and then give a better logic for that point (like how people really act in economic dealings).

Keen’s posting is clear in explaining the neo’s POV, but their POV is so wrong, so not the way business works, and so ignores what Keynes and other more accurate economist say (for example, that interest rates, outside of the Fed’s, go up when businesses think the future will be worse than the present, and go down when they think the opposite – Keynes’ liquidity preference), that trying to follow the neo’s results in eyes-gazing-over. You know it’s wrong but you can’t stop their talking…

With the point in mind, that in order for someone to discredit a theory,they must first show a working understanding of what the theory implies.I get that.

My opinion is that economics in general, and these models,and assumptions in particular are just “rules of thumb”.They are something to have a general idea of, without letting yourself get lost in the weeds of the facade of the precision or accuracy they don’t actually contain.The world is too complex,too many actors on the stage who at every given time are reading from different books.

And everyone who uses “rules of thumb” knows, they seem to work a lot of the time.When all you need is “good enough”.But they don’t even begin to deal with specifics that arise from any individual project that has its own specific perameters,characteristics,flaws,etc;and need to be taken from there to a desired end that is intended to remediate “what is”, to get it to “where it should be”.

I could see the use of these “mind games”, to train wanna be economists on the “gist” of what is monetary theory,policy ,etc…It is a scenerio where just getting your head around these things(even seeing their flaws),is a useful practice.Like hitting a heavy bag..It is just practice.But it ain’t a fight.

Where the world is now, and it has always been, is we are in a fight.We need names, we need the specifics of who,what,when,where,how,why,etc.We do need to debunk these “rules of thumb”,because they are the windmills we are fighting today.They are the ghosts who cannot be touched, which keep us busy as to not attack our actual adversary.

I see a self replicating fascist/federalist elite who are within the community of intrest of the corporate behemoths controlled by the monied aristocracy of the world.They pervert our lives so that we spend too much time taking from others, and not enough on securing for ourselves;”life.liberty.and the pursuit of happiness”.The sustainable notion that the world has an abundant nature that can sustain us, if we adhere to natures laws, and use wisely the gifts of nature.

These ideas of sustainability must be nourished in the youth.The world now is on a path to destruction.The kids need to be shown that the changes can be made.how ,will be up to them(considering we are only getting the garden ready at this point).But they should be doing some “models” of their own.How would wall st react if the fed were dissolved into the treasury and a plan like “the NEED ACT” HR2990 112th congress were enacted?Rather than haveing skyrocketing debt,we were to have “money”, to spend on things like a universal heathcare system, a universal educational system.They may live at a time when the first four months of the year of their wages weren’t going to pay taxes, so their tax dollars were funneled to corporate industrial complexes like:military industrial complex,agriconglomerate industrial complex,heathcare indutrtial complex,prison industrial complex, academic industrial complex.Media industrial complex,etc….Wile all these complexes arose out of what we need to sustain,life,liberty and pursuit of happiness,they are now solidly opposed to that goal,for us….now we have liberty and justice for some.If everyone could “save” two months of taxes, and just take that time off for contemplation,as to what is sustainable,which politicians are lying,and what ideas they should and should not support.

These are things that are real, and no model really takes into account;their schennanigans.

I also would say that as far as models go. to describe the real world, we have to get past the two dimensional models, and have at least three dimensions, so that many of the absolutely unrelated scenerios can go past each other and have even less of a chance to intersect, as a two dimensional model seems to imply too often.Then we can throw in a fouth dimensional model where the lines can go around and around and come out like a ball of yarn.

Steve Keen: some questions.

From what I can tell, the concept of the IS curve is OK. Keeping in mind that the interest rate is the INDEPENDENT variable — something which Krugman actually appears confused about — it seems to be a coherent concept, based in very simple and empirically solid ideas. (Interest rates go up: people attempt to put more money in “bank accounts” / T-bills / etc. to get the interest. Interest rates go up: people attempt to borrow less and pay down debt to get out from under the interest. Same if interest rates go down.)

Furthermore, empirically, the curve does seem to slope the way Krugman thinks it does. People (and firms) are more sensitive to the dangers of borrrowing than to the benefits of saving, so there’s an asymmetrical response: high interest rates reduce borrowing more than they increase saving, roughly speaking.

Now, there’s a case where people (or firms) feel compelled to borrow because they don’t have enough income to operate on a going-concern basis, and that should distort the curve. But on the whole, the IS-curve concept seems solid, as long as you remember that interest rates are an independent variable.

It’s the LM curve which seems seriously problematic, and in fact contrary to the way the world actually works.

Does that comport with your view?