By Timothy J Hatton, Professor of Economics, Australian National University and University of Essex. Cross posted from VoxEU

The height of today’s populations cannot explain which factors matter for long-run trends in health and height. This column highlights the correlates of height in the past using a sample of British army soldiers from World War I. While the socioeconomic status of the household mattered, the local disease environment mattered even more. Better education and modest medical advances led to an improvement in average health, despite the war and depression.

The last century has seen unprecedented increases in the heights of adults (Bleakley et al., 2013). Among young men in western Europe, that increase amounts to about four inches. On average, sons have been taller than their fathers for the last five generations. These gains in height are linked to improvements in health and longevity.

Increases in human stature have been associated with a wide range of improvements in living conditions, including better nutrition, a lower disease burden, and some modest improvement in medicine. But looking at the heights of today’s populations provides limited evidence on the socioeconomic determinants that can account for long-run trends in health and height. For that, we need to understand the correlates of height in the past. Instead of asking why people are so tall now, we should be asking why they were so short a century ago.

In a recent study Roy Bailey, Kris Inwood and I ( Bailey et al. 2014) took a sample of soldiers joining the British army around the time of World War I. These are randomly selected from a vast archive of two million service records that have been made available by the National Archives, mainly for the benefit of genealogists searching for their ancestors.

For this study, we draw a sample of servicemen who were born in the 1890s and who would therefore be in their late teens or early twenties when they enlisted. About two thirds of this cohort enlisted in the armed services and so the sample suffers much less from selection bias than would be likely during peacetime, when only a small fraction joined the forces. But we do not include officers who were taller than those they commanded. And at the other end of the distribution, we also miss some of the least fit, who were likely to be shorter than average.

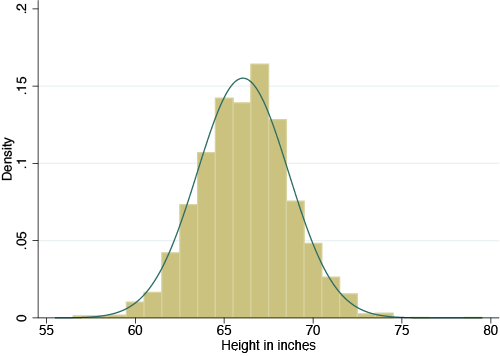

Figure 1 Distribution of heights in a sample of army recruits

Figure 1 shows the distribution of heights in our sample. The average is almost exactly five feet six inches (168cm) (for reasons that are unclear the mode is at five feet seven). Although there was a minimum height requirement of five feet three inches, this was breached early on in the war with the establishment of the so-called bantam regiments (later merged into conventional regiments). Indeed, nearly 10% of our sample measured up at less than five feet three.

Correlates of Height

So, are the heights of these servicemen linked to their socioeconomic origins, and if so, how? Economic historians have often associated the heights of servicemen with characteristics of their birthplace, but typically with no information about their individual household circumstances during childhood. Thus, it remains unclear whether the locality effects simply represent average household conditions (a rough proxy for the individual’s circumstances), or whether they genuinely stem from the locality.

In order to capture household conditions during childhood, we have traced the soldiers whose heights are represented in Figure 1 to children in the 1901 census of England and Wales. We have a remarkably high rate of successful matches of about 80%, which is much higher than is achieved in other studies that rely on historical record linkage. We typically have details of birthplace and next of kin from the army record, but this is mainly because we have searched for each case individually, much as a genealogist would.

So what do we find?

• Looking at household conditions alone, we find that those from middle class households were half an inch taller than those with working class origins

• We also find that servicemen were shorter the more siblings they had, consistent with the idea of a quality-quantity trade-off in health

On average, those with six siblings were more than half an inch shorter than those with one. This is not just a result of crowding in the household as, in addition, those living in households with more than one person per room were a quarter of an inch shorter than those living in less crowded conditions.

It is interesting to note some things that don’t matter very much. One of them is the individual’s birth order. Also, if the serviceman’s childhood household was headed by a female, or if his mother was an earner, seems not to matter much, contrary to the views of some contemporary observers. On the other hand, a larger share of earners in the household seems to have had a negative effect on height, perhaps because of the priority given to earners in the distribution of household resources.

Did the locality still make a difference? We find that it made a big difference, even after accounting for the socioeconomic status of the individual household. But we do not find the negative effect of population density (population per acre) that some have found for the mid-nineteenth century. Nor do we find that living in an agricultural district confers much height advantage, as studies of much earlier eras have found, probably because market integration had diminished the benefit of living close to food sources.

Locality effects come through three key variables.

• Two negative effects are the proportion of households in the district that were severely overcrowded (more than two persons per room); and

• Whether or not the district was highly industrial. Those that grew up in industrial districts suffered a height deficit of more than half an inch

• The third is that the greater the illiteracy rate among young married women in the district, the shorter the soldiers who grew up in that locality. This does not seem to be an income effect: there is no negative effect from illiteracy among young married men

These locality effects are surprisingly powerful. So how did they work? They seem to have affected height through their influence on the local disease environment, for which the infant mortality rate is a good proxy. By itself, infant mortality had a strong negative effect on height – an effect that amounts to a difference of an inch between districts with the lowest and highest infant mortality (10th versus 90th deciles). In turn, infant mortality is strongly influenced by overcrowding in the district, its industrial character, and its rate of female illiteracy.

• These results indicate that while growth during childhood was influenced by the socioeconomic structure of the household, the local disease environment mattered even more

This contrasts with modern findings in which local conditions exert only small effects once household circumstances are taken into account. Disease was transmitted more readily in overcrowded communities, and industrial pollution added to disease burden. Perhaps not surprisingly, female education provided a basis for the diffusion of better child nurturing practices.

The findings reported here have significant implications for understanding the dramatic improvement in health for subsequent generations. In the following half century the height of males increased by about two inches. This was a period of rapid fertility decline, which would have increased height by about a third of an inch. It also witnessed a decline in the rate of infant mortality from around 15% to just 6%, which would have added one and a third inches.

Sanitary reforms and housing renewal improved the urban environment, and industry gradually became less toxic. Illiteracy disappeared while average education increased by 2-3 years. More and better education, combined with modest medical advances, brought better understanding of the benefit to children of nutrition and hygiene. Together, these developments help to explain the apparent puzzle of the improvement in average health status during a period of war and depression that predates the advent of universal health services.

See original post for references

The perennial question: is bigger necessarily better? Although not conclusive, it appears to be the case.

Depends on how you define better.

Certainly shorter height has not been a negative for Asian populations. It helps that they can get by with smaller everything.

According to the article the survey did not include officers. There are British accounts from WW 1 of enlisted men hanging on to officers to finish a march, and of officers being sent out to bring in enlisted men who had collapsed along the way. Maybe officers didn’t have to carry the heavy equipment that enlisted men did, but it also seems likely that the middle class or above men who became officers were a good deal more robust than the poor/working class enlisted men. Could it be that the latter simply didn’t get enough food during childhood?

A 1903 Springfield rifle with bayonet would be 4’6″ long. That’s pretty unwieldy for a 5’3″ soldier.

Also, I’m sure after a few months of rations and trench life, the enlisted men were much more easily exhausted than the well-fed officers.

Only cheese-eating surrender monkeys march on their bellies. The stout British Fusilier fights on blessed pride in Queen and Country alone! Which means said Queen need feel no obligation to pay us when we return as conquering heroes. A rousing speech, declaring she would fight alongside us in the battle already won is enough.

So we control infectious diseases and eat more and get bigger. Gosh! Tax dollars well spent here. You’d think, given peak everything, we’d get sensibly smaller, like the dinosaurs and birds did once oxygen was less abundant. And a big man makes a bigger target. There is a rumour it took 18 months feeding on meat to make an English navvy. It was boiled rather than roasted.

Supposedly the German trench accommodations in WW1 were pretty good while the British ones were appalling. One might expect the opposite since the British Empire was richer. Hardship is to be endured when necessary but the deliberate infliction of hardship on OTHERS for their supposed moral benefit has NO support in Scripture that I can see. Rather, it fails the test of being kind and good. So where do the Brits draw their moral instruction from and what possible good do they expect from it since God is NOT an Englishman and even if He were, He would not show them special preference?

I reckon the British upper middle class of that period had other problems to contend with……..such as the CURSE OF THE CLAW.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2nv5Mn9OVA

Boxing records would I think back these facts up. If I remember rightly the flyweight division was the most competitive & populous in Britain at that time, I think the equivalent now is middle to super middleweight.

Perhaps it is also genetic but we have lots of immigrant workers in our area from East Timor who are very small, in particular in the leg department. I imagine to come all this way to do the jobs nobody else wants to do they perhaps come from a society that suffers from the above problems.

Post MTV generation kids vs Depression era kids

A study

Discuss..

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRiPhXe91dg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KezwDfFcFhU

Thinking back thru our families’ histories: Bill’s grampa was a second generation German immigrant, the son of a butcher and always well fed. But not overly fed. He was a skinny 5’7″ but he behaved with the macho of a bigger man. Lived to 96. He used to say that all our health problems were due to “just too much good food nowdays.” It seems entirely possible that just a little more food for undernourished troops (as children) who were 5’3″ might have made a small difference. It also seems possible that a little goes a long way because, here in this country, we have an epidemic of obesity and diabetes. So more is not better. We aren’t getting taller fast enough to be trim. So getting taller is a multi-generational process probably. Getting fat is just a few too many calories. If the question is, Why were we so short before? The answer is that our DNA is ultra-conservative. Otherwise we’d all be giants now.

I’m six’one”, and I’m about the same height as my maternal great grandfathers and their brothers who came from small/mixed farms (they weren’t share cropping or land barons, but yes, my maple syrup does come from trees grandpa planted) in Vermont and Quebec. My maternal, male cousins tend to have similar sizes despite not having grown up on farms as opposed to our elders.

On the flip side, my father’s father was a little shorter than my father, 5’11”, but in pictures, that grandfather is noticeably larger than his immigrant parents.

“in their late teens or early twenties when they enlisted”: I wonder whether many of them carried on growing after enlistment. Presumably there’s no way of finding out.

The importance of the local disease environment and of the mother’s lack of education are discoveries that are interesting and non-obvious, a rare event in social science.

I noticed this pearl in the article:

This has great contemporary relevance. Our planet is dangerously overpopulated, and many people are resistant to acknowledging the benefits of contraception and small family size. If lower income parents (or any parents) really love their children, they will make choices that benefit the health of their children. Clearly, having fewer children means healthier children.

IIRC British soldiers at the end of the C17th/early C18th were taller than their French counterparts. This has been attributed to the diet of beef which they enjoyed as the economy boomed in the later part of the 17th century.

Is this part of the reason for the result at Blenheim which of course saw the beginning of the end of the French dominance of Europe and its supercession by Britain?

“But we do not include officers who were taller than those they commanded.”

For the benefit of other commenters, it is worth noting that the exclusion of officers is largely because the digitised records do not include those of officers, which are in separate record series (which can only be consulted in paper at The National Archives, Kew).

“Although there was a minimum height requirement of five feet three inches, this was breached early on in the war with the establishment of the so-called bantam regiments (later merged into conventional regiments). Indeed, nearly 10% of our sample measured up at less than five feet three.”

5’3″ was the minimum for infantry, different trades in other branches of service had differents minimums, and I have been told there were maximums for some roles too (eg drivers in the artillery and Army Service Corps – presumably for much the same reason that jockeys tend to be small, adding less weight to the horses).

It would alos be interesting to see if any change in height over the period of service can be measured, given that calorie intakes may well have actually been higher on army rations, and medical care was more available. For example a colleague recently wrote about Lance Bombardier William Horace Kitt whose records show that he grew 5.5 inches during his service (this actually began in the Territorial Force before the war when he was under 18).