This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 90 donors have already invested in our efforts to shed light on the dark and seamy corners of finance. Join us and participate via our Tip Jar. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current target.

Yves here. This post describes the “new normal” of the role bank reserves play in hitting short-term policy rate targets in the US. The author ends on a cheery note about how the abnormal-looking situation we have, in particular super-low interest rates, could persist for a very long time. The author contends that the way one reacts to these new procedures and their results will reflect your monetary aesthetics, as in your beliefs about the way central bank balance sheets and reserves should look. However, given the way that negative short-term real interest rates are stoking financial speculation at the expense of real economy investment (a trend that was already well underway even before the crisis containment program turbo-charged it), one can hardly see a continuation of the new normal of low growth and redistribution to top earners as a positive development.

By Jérémie Cohen-Setton is a PhD candidate in Economics at U.C. Berkeley. Originally published at Bruegel

What’s at stake: Since 2008, the asset purchases made under QE have increased drastically the aggregate level of bank reserves, thereby weakening the control of the Fed’s federal funds rate. On Wednesday 17 September 2014, the Federal Reserve announced a revised plan for the mechanics of how it will raise interest rates from near zero despite large excess reserves.

The primary tool for moving the fed funds rate will be the interest rate the Fed pays on the money, called excess reserves

Real Time Economics writes that as part of the so-called exit strategy, the Fed will continue to rely on its benchmark federal funds rate, an overnight interbank lending rate, as the key rate used to communicate Fed policy. But the primary tool for moving the fed funds rate will be the interest rate the Fed pays on the money, called excess reserves, that banks deposit at the central bank. The Fed also will use an interest rate it pays on trades called reverse repurchase agreements, or reverse repos, to help ensure the fed funds rate stays in its target range.

The Old Way of Raising Rates

Michael Woodford writes that it will be an interesting experiment in monetary economics because the Fed will be attempting to control short-term interest rates in a situation where almost certainly its balance sheet is going to be unusually large. That means that there are going to be extraordinary quantities of excess reserves in existence, and this means that Fed control of short-term interest rates will not be achievable in the way that it always was in the past: through rationing the supply of reserves. The Fed would maintain a fairly small supply of reserves, small enough that there was indeed an opportunity cost of reserves, and it could adjust that opportunity cost fairly precisely through relatively small changes in the supply of reserves.

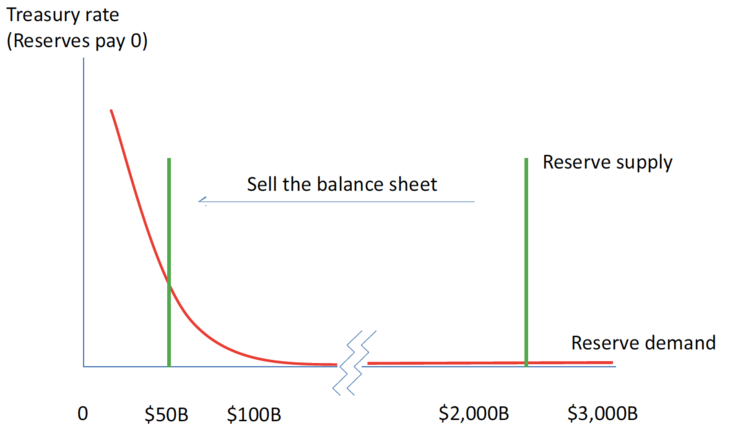

John Cochrane illustrates in the figure below the standard story for monetary policy, and one option for the Fed when it wants to raise rates. In this story, the Fed controls interest rates by rationing the amount of non-interest-paying reserves. Banks must hold reserves in proportion to their deposits. If the Fed sells bonds, taking back reserves, the banks must get along with fewer reserves. They bid up the Federal Funds rate they pay to borrow reserves from each other. Treasury rates and other rates rise by arbitrage with the Federal Funds rate. So all interest rates rise.

The New Way of Raising Rates

Attention turned to an alternative approach to monetary policy implementation by effectively “divorcing” the quantity of reserves from the interest rate target

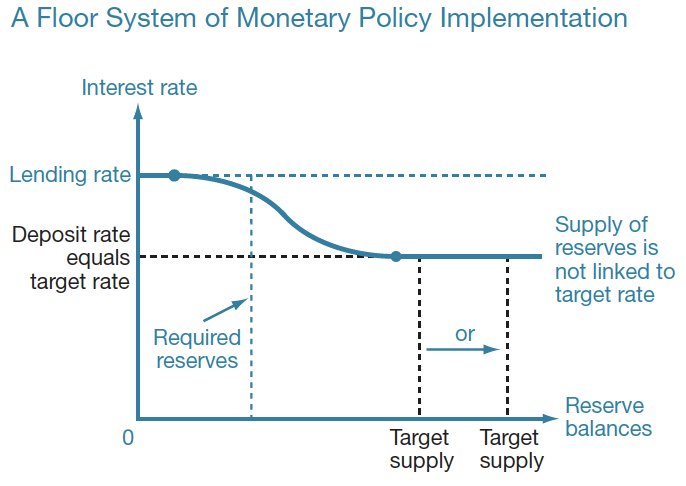

Todd Keister, Antoine Martin, and James McAndrews writes that recently, attention has turned to an alternative approach to monetary policy implementation by effectively “divorcing” the quantity of reserves from the interest rate target. The basic idea behind this approach is to remove the opportunity cost to commercial banks of holding reserve balances by paying interest on these balances at the prevailing target rate. Under this system, the interest rate paid on reserves forms a floor below which the market rate cannot fall. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand adopted a particular version of the “floor-system” approach in July 2006.

Prosperity can only begin when ‘subjects’ are given their independence and sovereignty from imperial rulers. Imperial rulers are not interested in developing their ‘subjects’ infrastructure, education, nor self-determination but are only interested in how much wealth they can extract for themselves. So it is with policy makers who decide on interest rates. Controlling rates is another tyrannical way of subjugating the masses to submit their resources to the very rich. Unfortunatly this is a well practiced policy in recent years. Central bankers are there to help their wealthy friends after all. They don’t even try to hide it.

We need an Occupy Central Bankers.

This also looks like an attempt to stabilize short term interest rates on money market funds so we don’t experience another run on them. This would make money market funds essentially accounts at the Fed and they would be safer than commercial bank deposits. But this should also mean that these money market funds shouldn’t leak into the tri-party repo system where the Fed could end up backing various failed speculation. This money could come from people willing to take more risk for more interest. The Fed should concentrate with the Treasury to promote the public interest.

Count me as “not a fan” of the new normal. The entire financial history of the last decade has been the mis-pricing of risk. Any non-zero interest rate paid on reserves 1) establishes a risk-free way to grow a bank’s balance sheet – albeit painfully slowly – and 2) incentives – albeit only marginally – doing NOTHING with some portion of a bank’s capital. I know, I know, banks are always looking for ways to shovel capital out the door. But with the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and the limited number of players able to take advantage of this system, there mathematically MUST be an equilibrium zone where the returns from simply accumulating a sufficiently large pile of risk free money equals the risky returns generated from lending out a smaller pile to businesses and homes.

Interesante.

An enigma seems at play.

In the face of an accepted operative tenet that ‘the government IS the monopoly issuer of the currency’….. the money supply thus being eminently controllable in support of achieving economic output potential …… here we are faced with a barrage of modern economists that are worrying about the effects of the CB’s excess reserve status, and it’s mirror image as the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, on the money authority’s ability to manage interest rates as outlined in the FOMC’s policy memoranda.

Heaven forbid the outcome !

But the only thing that can happen in a reserve-dominated policy environment is a bit of ‘slack’ in the string used to control interest rates……..so, is that a problem, really, and for whom? IF,’the government is the monopoly issuer of the nation’s money’, then control of the supply of money in circulation is already under its direct control, somehow, and the resulting effect of excess reserves on the level of interest rates may matter to the interest rate speculator, or to those already ‘victimized’ by ZIRP.

But obviously (?) it cannot have any effect on the level of the supply of money, which can be the ONLY inflation or deflation determinant , because the government IS the monopoly issuer of the currency.

Not to worry.

Under control.

Que no?

When the Fed began paying .025 for excess reserves, I think the reason was the federal deficit ballooned after 2009. The way it was financed, while the overnight interest rate was held at near zero, involved the Treasury selling its bills to the big banks by law at auction, then the banks selling the treasuries to the Fed for reserves, then the banks parking the excess reserves at the Fed. This was monetizing the deficit a new way, by sequestering the new reserves created at the Fed and exploding its balance sheet while scant money trickled down into the economy. It shouldn’t go on forever, because of the interest the Fed has to pay to cause the banks to accumulate the excess reserves is a creation of reserves itself. I’m a little tired of the idea that central banks should target the overnight interest rate banks charge each other for borrowing reserves as the variable policy tool. I think interest rates should float, finding their own level in the marketplace. To do that, the central bank could auction off a constant, limited supply of reserves periodically. First, they will have to reduce and stop paying interest on the excess reserves.

I think I already told y’all so. The Fed will increase the pay-out on excess reserves and run off its own huge balance sheet holdings via reverse repos until their terms expire. But note that the banks will get paid for doing nothing with their excess reserves. Currently the rate is .25%, which amounts to about $4.5 bn annually, but as the rate rises, so will the annual payout. And as interest rates rise on T-bonds, the lower yields on the bonds the Fed currently holds will imply an increased haircut on the reverse repos, which means the Fed won’t be able to drain the full amount of “money supply” it has already issued. The only way it could fully drain the full amount would be if the Treasury directly gifts the Fed with extra T-bonds, which is effectively to re-capitalize the Fed. And where do the higher payments on reserves come from, if not from being deducted from the payments the Fed would “normally” remit to the Treasury. IOW QE policies end up adding to the fiscal deficit/debt and are really fiscal policy all allong, though in a peculiarly dysfunctional, distortionary, and unauthorized form.

Sorry to complain, but the ad bad with the ad for the motley fool is blocking the content I want to read, and I can’t get rid of it. everytime I scroll, it moves too