Yves here. When normally MEGO (My Eyes Glaze Over) inducing tax schemes become a topic of national debate, it’s because despite their complexity, they’ve become too big and ugly to ignore.

Mind you, multinationals already have tons of ways to escape from the tax man, starting with clever transfer pricing so as to claim pretty much all their profits occurred in super low tax domiciles. But the trick that has caused consternation is tax inversions. In crude terms is using mergers as a way to move the headquarters of a company from a higher tax to a lower tax jurisdiction. The acquired company in the lower-tax location becomes the new parent company.

The Treasury Department was so concerned about potential revenue loss that it took measures to reduce tax inversions. This article argues, in effect, that while Treasury may have made it more difficult, that the incentive to enter into inversion remains. The analysis is clever and compelling. It also happens to debunk the argument made by defenders of Antonio Weiss, the Lazard banker nominated to a Treasury post who is fiercely opposed by Elizabeth Warren. Weiss was an important advisor on the Burger King-Hortons merger, the deal that (according to the Wall Street Journal) that led Treasury to put rules in place to combat tax inversions. The defenders argued that the tax rates between US and Canada weren’t all that different, so that the tax considerations weren’t important to the deal. This article mentions the Burger King deal and the difference between US and Canadian inbound divident repatriation tax rates at 10%, more than enough to be motivating.

The authors contend that the fight over tax inversions is effectively a arms race, and tax authorities will almost certainly have to implement more measures as experts find ways to circumvent the obstacles.

By Maarten van ’t Riet, Researcher, CPB and Arjan Lejour, Programme leader, CPB. Originally published at VoxEU

The recent actions of the US Treasury to rein in corporate tax inversions leave their rationale largely intact. This column discusses new evidence suggesting that the potential tax benefits of inversions are still huge. The recent Treasury measures raised legal obstacles, but the heart of the problem remains unaddressed. At some point a new technique is likely to be found to circumvent the new measures – just as happened with earlier measures. This is a worldwide problem.

Corporations undertake many manoeuvres to reduce their taxes. One that has recently attracted a good deal of attention is called ‘tax inversion’. This involves a restructuring that shifts the multinational’s legal residence abroad. Generally this involves little or no shift in actual economic activity, but can substantially reduce the company’s tax bill.

A flux of planned tax inversions by large US-based corporations and concern for the erosion of the US corporate tax base prompted the US Treasury to announce measures aimed at reining in this form of tax avoidance. For example, pharmaceutical company Abbvie planned a $54 billion acquisition of an Irish-based company Shire – a merger that would have involved tax inversion. The deal was called off at the end of October, with Abbvie citing the new Treasury measures. Other deals, however, are going ahead.

Several tax analysts have claimed that the Treasury actions may not seriously affect the pending merger deals.1 Basically the reason for this is that the tax rationale for the inversions does not change. The tax benefits of inversion most often mentioned are the switch to a country with a territorial (exemption) system instead of a worldwide (tax credit) system and a lower rate of corporate income tax. The US taxes worldwide corporate income, with a credit for foreign taxes, whereas in a territorial system foreign corporate income is exempt from taxation in residence countries under territorial systems. Specific to the US tax code is that the tax liability is only incurred upon actual repatriation of foreign earnings. Repatriation, and thus taxation, can be deferred – a practice widely used by US multinationals (see, for instance, Zucman 2014). The Treasury measures are generally acknowledged to be effective when accessing accumulated foreign earnings is the prime motive for tax inversion.

Previous Policies to Discourage Tax Inversions

Prior to September 2014 the US already had anti-inversion rules in place. One important rule was, and still is, that the tax benefits of inversion are denied if the original US shareholders own 80% or more of the post-inversion company. This rule was introduced with the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. Basically, it ended inversions to tax havens where no real business activity takes place, such as Bermuda and the Cayman Islands (Marples and Gravelle 2014).

The 80% ownership requirement also explains why mergers are a vehicle for tax inversion – the foreign company brings in non-US prior ownership. However, when a US company is large it may be difficult to find a suitable foreign company to merge with, and various ways have been used to meet the 80% rule. The Treasury specifically targets these actions to size down the US company or to beef up the foreign company, but does not touch the tax benefits per se. They only raise the hurdle to gaining access to these benefits (US Treasury Fact Sheet 2014).

New Research on International Tax Differences

In a straightforward analysis of the tax benefits of inversion, we conclude that the profitability of a tax inversion mainly depends on the dividend repatriation tax rates from the rest of the world (Van ’t Riet and Lejour 2014).2 We consider the international corporate tax system as a network of 108 countries including tax havens.

• For each country pair we determine the tax cost of repatriating dividends directly.

• Given these ‘tax distances’, we employ an algorithm that finds the ‘shortest tax route’ between each pair of countries in the network.

The algorithm is very much like the one in the navigation tool in your car. For 67% of the country pairs, an indirect tax route through other countries is found to ‘cost’ less tax than direct dividend repatriation. This finding can be taken as an indication of the divergence of national tax codes.

We illustrate the potential benefits of tax inversion with the repatriation tax rates on direct routes. These bilateral tax rates are constructed from the general rate of non-resident dividend withholding tax of the source country and the double tax relief method of residence country. For relief methods other than participation exemption, the corporate income tax rate of the home country of the investments must also be taken into account. Moreover, countries may have signed a double tax treaty, reciprocally agreeing on reduced withholding tax rates and, possibly, on a more lenient double tax relief regime for the treaty partner.

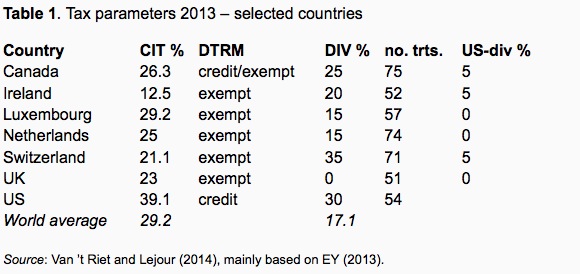

Table 1 shows this information for a selection of countries: the US and a number of candidate inversion countries. The tax parameters are the corporate income tax rate (CIT), the double tax relief method (DTRM), the general rate of the dividend withholding tax (DIV), the number of treaties, and the US withholding taxes for the six treaty partners shown in the table. Canada grants participation exemption for dividends from its treaty partners, 75 in the set of 108 countries, and thus de facto it has a territorial tax system.

In the analysis we assume throughout that the corporate income taxes of the source countries will be paid. Moreover we assume that the after-tax profits in the host countries are not affected by the tax system in the residence country. In fact, we ignore tax planning strategies such as transfer pricing, hybrid constructs, intra-company loans, royalty payments, etc.

Large Differences in World Average Dividend Repatriation Tax Rates

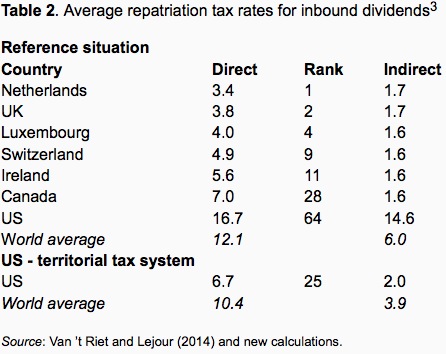

Low average, GDP-weighted, tax rates for inbound dividends make a country attractive for corporate residence. The Netherlands and the UK head the ranking of countries in this respect, with average rates of 3.4% and 3.8% (see Table 2). In sharp contrast, the average rate for the US is 16.7%, ranking 64th. Other candidate inversion countries, such as Ireland, can also be found near the top of the list. Canada, candidate for the Burger King tax inversion, is ranked 28th – it has an average inbound dividend repatriation tax rate of 7%, still a difference of almost ten percentage points with the US.

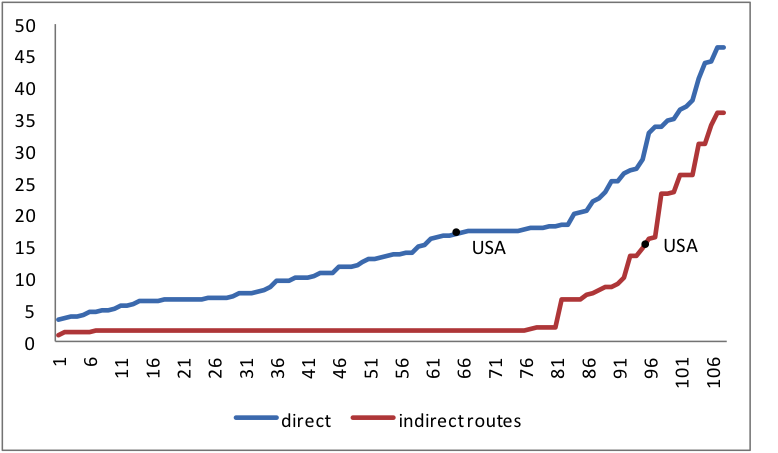

The possibility of indirect tax routing increases the differences in repatriation tax rates. Multinational corporations can channel investments through third countries to take advantage of tax treaty provisions not found on the direct route. The full potential tax benefit of this treaty shopping amounts to a worldwide average reduction of six percentage points of the tax burden for multinationals. For dividend flows to the US the average tax rate falls two percentage points. Treaty shopping creates a well-connected group of some 80 countries among which dividend repatriation is inexpensive, with average tax rates below 2% (see Figure 1). The group contains the EU countries and various tax havens.4 Countries with a worldwide tax system are not part of it.

Figure 1. Distributions of average dividend repatriation tax rates

Source: Van ’t Riet and Lejour (2014).

Finally, as an illustrative example, we report the calculations for the US applying a dividend participation exemption, which implies a territorial system. Its average inward repatriation tax rate drops to 6.7%, ranking 25th, above Canada (see Table 2). And with the full potential benefit of treaty shopping the rate becomes 2%. In this situation the US would be part of the ‘well-connected’ group of countries.

Concluding Remarks: Pressure on the System Remains

We have hypothesised that the tax benefits that can be realised on repatriation of foreign earnings are the main driver for tax inversion. Dividend repatriation tax rates have been computed based on parameters of the international corporate tax system. For the US the rate is more than ten percentage points higher than the rate of a number of European countries and tax havens. This constitutes a strong incentive for tax inversion. We do not take into account possible opportunities for earnings stripping that inversion may create. However, since we are dealing with corporations with foreign affiliates, we submit that the opportunities for base erosion are already manifest.

The recent Treasury measures raise legal obstacles, which may make inversion costlier. Moreover they may have eliminated the tax benefits on accessing accumulated past foreign earnings. At the same time we observe that the measures do not target the potential tax benefits regarding future foreign earnings. Legal intervention may of course be effective. Marples and Gravelle (2014) argue that the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 has put an end to the first wave of tax inversions in the late 1990s and early 2000s.Our analysis suggests that the pressure on the system remains. And at some point in time a new technique will be found, just as happened with the Jobs Act which did not prevent a second wave of (pending) inversions. Not surprisingly, the Treasury has announced the possibility of new measures to curtail tax inversions.

Endnotes

[1] Robert Willens: “not a mortal blow”; http://blogs.wsj.com/pharmalot/2014/09/24/inversion-rules-are-not-a-mortal-blow-to-pending-deals-willens-explains/.

[2] For details, see the background document on the CPB website (http://www.cpb.nl/en/publication/potential-benefits-tax-inversion-remain-huge-with-the-model-and-full-country-ranking).

[3] For the full table see the background document: http://www.cpb.nl/en/publication/ranking-the-stars-network-analysis-of-bilateral-tax-treaties.

See original post for references

Taxes do not get paid by other than the most ignorant in the society, especially in the USA. When the fiat note from the Fed is not money, then the tax scheme is known via the counterfeit source to pay a tax. In other words, the transnational corporations and all the corporations for that matter, could more than pay whatever a tax would be, simply by printing a fiat note or manufacturing a digital voucher from the computer. Almost all industry has to pay to play and the Fed is the piper which SWIFT swiftly sweeps all the ‘wealth’ exactly where decided.

Another book needs to be written Yves.

Society gets decided, taxes and all the decisions about “money”, at Inn of Court, Inns of Courts.

Pay to learn how to do society as a business. Called “lieyers”.

Thanks for sharing!

Yves ~ I’ve ~~an idea. Play on word and pun intended. Actually, the idea is an on-line license to practice law. Take the law, the real law that Thomas Jefferson meant, and the law gets taught on-line with every person in the USA that is a “CITIZEN”. One and all can educate and then become a “Citizens’ Attorney-At-Law”. Fulfilling a Founding Father’s dream. Thomas Jefferson may find himself forgiven for being a Virginia Slave Trader. In your new book about Inn of Court (as said, where Thomas Jefferson went to study to be the “polished argument winning lawyer”), you can introduce the classes. And, what about William and Mary’s as the school to set-up the on-line education partnership contract? After all, in tracking and tracing the money, the Bank of America appears to be the holder of the IOLTA (Interest on the Lawyer’s Trust Account), for the B.A.R.s. IOLTA has been challenged more than one time, and no less that two times SCOTUS decided IOLTA is not going to be other than what it is. What is IOLTA, in reality? Said to be the fund to provide for those that can’t afford an attorney.

Thomas Jefferson would be finally able to to stop the slave trade, via on-line teaching us all how to be licensed attorneys to meet obvious opposition to the same old story. Human flesh trade changed form and became more civilized in the facade only.

How many Americans were provided IOLTA during the booms and busts via the Fed? Wonder how the business is run as Transnational America? We must be on-line licensed members, in the business of contracts as the most simple to the most complex.

Understanding the compensation for a secret society deciding our lives is now in a transparency, that is, the Inn of Court has definite script that is taught, and the “money” is how the flesh-trade gets to be in a hidden cloak of “professional human being (NOT)”. Dressing in robes, and then the cost to hire a “hired gun” like David Bois Super Lawyer, who got to be in the BIG Court, and depose the “Government Treasury” / Fed’s Tim Geithner, Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson. A COALITION OF CITIZENS’ ON-LINE LAWYERS / ATTORNEYS-AT-LAW, most certainly could do the SUPER LAWYER work.

Contact WALKER F. TODD, you can find him on-line. He is an important contact for you.

Thanks for your amazing work and the blog, too. What an incredible photo gallery. I am an artist that has spent my life seeing animals as my most favorite and almost exclusively, love to co-create in a form of art.

Best to us all, now in 2015, and beyond into eternity

The Sustainable Economies Law Center (SELC) has a program they call “Like Lincoln” that allows people to earn their lawyering creds by apprenticing with a practicing attorney. CA law still allows for this form of legal training, as do some other states, iirc.

http://likelincoln.org/

Financial/Tax inversion coup: Merck KGaA (Germany) buys out Sigma-Aldrich (US), though not completed. Sigma has a larger market share in North American than Merck along with their rather large footprint in Canada and Mexico.

I’m all for raising taxes on the wealthy – a much more direct and successful approach to distributional issues than net deficit spending – but I don’t get the extended focus in American political economy on regular income taxes paid by large corporate entities.

The major tax issues are the non regular incomes earned by the people who run and own the TNCs. Plus the taxes not paid when they “donate” to “nonprofit” corps like universities and hospitals.

The share of taxes paid by corporations in aggregate has declined a ton. It was 33% in 1952 and is 10% now. And remember, top marginal tax rates were 90% back then.

http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2014/aug/28/bernie-s/bernie-sanders-says-tax-share-paid-corporations-ha/

I hear you on the change.

But maybe rather than being a problem, it’s an opportunity to focus on individual income and social insurance tax policy instead of trying to recreate a corporate environment that doesn’t exist? For example, universities, hospitals, courts, police departments, prisons, big 501c3s, etc. are much larger today than after the war. So many of their employees are paying individual income and social insurance taxes. And many of the employers are paying social insurance taxes. But many of the employers are tax exempt corporations, or aren’t corporations at all, so they aren’t paying any corporate income taxes whatsoever.

Plus for me at a more abstract level, I don’t agree with the premise that corporations are their own entities, that they possess some kind of inherent worth distinct from the people who own and run them. My view is that they are simply a state-sanctioned legal construct allowing the individual owners to navigate a complex society without holding an ownership meeting every time office supplies need to be ordered.

Explicitly targeting tax inversions is likely a poor policy remedy. Corporate development efforts that pursue mergers consider at least a hundred different operational items on a checklist, with tax considerations representing one or two items at best. Squeezing more tax revenue out of tax inversions will do little to raise significant tax revenue.

My Eyes Glazed Over at this: ” …the deal that (according to the Wall Street Journal) that led Treasury to put rules in place to combat tax inversions.”

Didn’t we fight a revolution once, citing “taxation without representation” as the reason? Maybe it’s time….

The U.S. is unique among advanced economies in its grasping approach to corporate taxation – both with respect to its marginal 35 percent rate (plus state taxes) and its worldwide tax system. Incorporating in the U.S. and doing business in the UK means you pay US taxes on both your US income and your UK income (net of a credit for the 20 percent UK tax). If you’re incorporated in the UK and do business in both countries, then you just pay UK tax on your Uk business and US tax on your US business. I would argue that by maintaining this system the US is leveraging its fading empire to extract as much tax as possible – note the identical and equally unusual worldwide tax system for US citizens and permanent residents. Deferral of US tax on offshore earnings is nice, but at some point companies need the cash and are forced to either pay up or do right by their shareholders by looking for another alternative.

You don’t understand how this works, do you?

The cash is offshore only for tax purposes. It’s all kept in banks in the US. Apple, for instance, was running what amounted to an internal hedge fund in Nevada.

And the history shows these companies do not “need” the cash. In the last tax holiday, IIRC in 2004, the companies that repatriated cash used it to pay executive bonuses and buy back stock. And large corporations are overwhelmingly net savers, as in they are disinvesting. With profit share at record levels of GDP, they could easily raise worker wages but refuse too.

Why not simply tax corporate transactions where they occur? Sold in the U.S. is subject to taxation in the U.S. This would require that the tax be based upon the transaction price rather than on the profit so as to avoid the subterfuge of “shifting” of profits. The question of corporate taxation would then be limited to taxing the value of export transactions given that the point of origin of the product would differ from the point of sale. Given that there is a balance of payments benefit to an economy that encourage exports the level of such taxes could be set at some level that takes the benefit into consideration. The entire topic is academic at best so long as the Congress is captured by the multinationals and their stake holders, but that’s an entirely other topic.