Yves here. As strange as it may seem, most economists loudly disputed the notion that the rise in commodity prices, particularly in the first half of 2008, was in large measure due to financial speculation. More and more analytical work (such as comparisons of price action in commodities trades on futures exchanges with ones that have large markets but are not exchange-traded, like eggplant, a staple in India, and cooking oil) have dented the orthodox view.

By Manisha Pradhananga, Assistant Professor of Economics at Knox College. Originally published at Triple Crisis

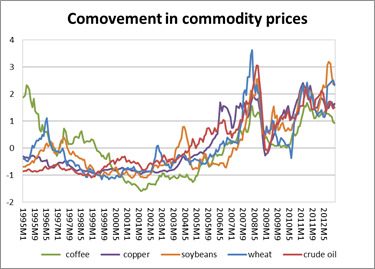

Remember the 2008-11 food price spike? It led to food riots in many parts of the world and increased the number of malnourished people by 80 million worldwide (USDA 2009). What many people don’t know about the price spike is that besides the rise in magnitude, it was distinctive for the breadth of commodities affected. Prices of a wide range of commodities including agricultural (wheat, corn, soybeans, cocoa, coffee), energy (crude oil, gasoline), and metals (copper, aluminum), all rose and fell together during this period.

Source: IFS, commodity prices. Normalized by demeaning and dividing by standard deviation of each series

It is not unusual for prices of related commodities to move together; if two commodities are either complements or substitutes in production or consumption, then a demand or supply shock in one commodity market may be transmitted to the other. For example, prices of certain industrial metals may move together if they are jointly used to produce alloys. Similarly, prices of grains such as corn, wheat, rice, and barley may move together if they are substitutes in consumption. However, commodity-specific shocks cannot explain co-movement of unrelated commodities, like the one observed in 2008-11 (Gilbert 2010, Frankel and Rose 2009). Many of the factors that were initially given as explanations for the price spike—such as drought, or the use of corn and oil-seeds to produce biofuels—are thus unable to explain this rise in comovement between commodity prices. Only factors that can affect many commodity markets simultaneously can be considered as explanations. In a recent paper, I focus on one of these factors, financialization of the commodities futures market, and explore the links between financialization and comovement.

The term financialization has been used in the broader literature to loosely describe a range of developments related to the rising dominance of financial markets, institutions, and interests in the U.S. economy since the 1970s. (Epstein and Jayadev 2005, Orhangazi 2008). This concept of financialization has been extended to the commodities futures markets, where financial actors and interests have similarly played an increasingly dominant role in the functioning of the market. Financialization in the commodities futures market refers to the massive inflow of investment in the market, and the rise of commodities as an investment asset. Futures contracts of commodities like oil, wheat, corn, soybeans, etc., are now considered a financial asset like stocks and bonds. The number of open contracts in U.S. exchange-traded commodity derivatives market increased six-fold between 2001 and June 2008, from around 6 million to 37 million in June 2008 (BIS). These new investors are neither producers nor direct consumers of the underlying commodities, and they increasingly control a large share of the market. Between 1995-2001 “bonafide” hedgers, who are producers and consumers of commodities, controlled 70% of the market in crude oil; by 2006-09 they controlled less than 43%.

This financialization of commodity futures markets may cause comovement between unrelated commodities in three ways. First, if commodity futures are bought and sold not based on expectations of future demand and supply of the particular commodity, but based on other portfolio considerations or herd behavior. This is especially true for financial traders who buy and sell commodity derivatives not individually, but as a group of securities based on pre-set weights of commodity indices like the Standard and Poor’s-Goldman Sachs commodity index (S&P GSCI). If a large portion of “investment” in the commodities derivatives market are controlled by such passive index trading (like they were in 2008), then it is likely that prices of commodities will move together. Second, if commodity speculators trade in two or more commodity markets, a fall in the price of one commodity may cause the price of other commodity to also fall. For example, if price of commodity A falls, speculators might have to sell commodity B to cover margin calls in the market for commodity A (in which they have a long position), thus leading B to move with A. Finally, as weight of energy commodities like crude oil is high in commodity indices like the S&P GSCI, so shocks (supply or speculative bubbles) in energy markets might be transmitted to other commodity markets, even if there are no changes in the fundamentals of those specific commodities.

In my recent Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) working paper, Financialization and the Rise in Comovement of Commodity Prices, I examine whether financialization of the commodity futures market can explain the remarkably synchronized rise and fall of commodity prices in 2008. For the empirical analysis, I extract common factors that explain trends in prices of 41 commodities and study the correlation between this common factor and the flow of money into the futures market. Results show that financialization can explain the rise in comovement between commodity prices after accounting for other macroeconomic variables such as demand from emerging markets and depreciation of the U.S. dollar. These results imply that as financialization of the commodities futures market proceeded and more traders entered the futures market, market liquidity increased. Much of the rise in liquidity was due to increasing investment in commodity indices, which meant that futures of unrelated commodities were being bought and sold together as parts of portfolios. This increase in liquidity across different commodity markets led to the synchronized rise (and fall) in commodity prices.

This growing influence of high finance on commodities has several ramifications. Commodities futures markets have existed in the United States since 1865, providing producers and consumers of commodities to hedge against unexpected changes in prices. But, as the futures market is taken over by financial interests and prices become more volatile, it may lose its usefulness for producers and consumers. More importantly, as prices will become more unstable, the financialization of commodities will lead to price spikes like the ones we witnessed in 2008-11. The most vulnerable people in the world will be affected the most because they spend higher proportions of their incomes on food and are unable to smooth their consumption over time. In 2008, a majority of those negatively impacted were members of women-headed households who had limited access to land and other resources. Most of the countries that were affected were poor, food-importing countries that neither had the budgetary means nor the option to restrict exports and shield their populations from high prices.

the financialization of commodities will lead to price spikes Manisha Pradhananga

Unlimited price spikes given the inelastic demand for food, George Soros’ “Theory of Reflexivity” and government-subsidized private credit creation?

Proverbs 11:26

the financialization of commodities will lead to price spikes Manisha Pradhananga

Unlimited price spikes given the inelastic demand for food, George Soros’ “Theory of Reflexivity” and government-subsidized private credit creation?

Why, it’s F. Beard reborn!

If you keep changing your name, but not your intrenched view, does that still count as a form of evolution.

Skippy… can’t wait till he peruses the “Today’s must read” in the links section. Its sort of a spoiler to his policy agenda, Rwanda again, yet on a larger scale.

Commoditied become speculative assets and prices are bid up. Greater costs require additional financing which results in expansion of the money supply. Weep, o austrians, for your causality is backward.

Weep, o austrians, for your causality is backward. Ben Johannson

Both of you are correct which is the point George Soros makes in his “Theory of Reflexivity”, ie. higher asset prices allow more credit creation which drives higher asset prices which allow more credit creation and so forth, ie. a positive (in the engineering sense) feedback loop.

Deregulation and poor risk weighing is the precursor to rampant speculation w/ perverse incentives established.

Skippy…. an agenda that seems to have over shot the mark a wee bit.

How does one regulate theft from the poor for the sake of the rich? How much is too much? How much is too little since the theft is done, purportedly, for the sake of the poor too?

How does one regulate sellers of dreck from bidding each others assets up and then serving it up to the poor as silk purse.

For myself… its curious how some stripes always utilize the downtrodden as a maypole, when they have zero power, power that was taken away by the so called libertarians, yet they are the first to invoke the downtrodden’s plight.

At this juncture you might want to have a look at the credit markets and it’s about income and assets not tight lending w/ high asset prices.

For those who somehow missed it, the reasons for this weakness revolve around a mixture of inter-related economic, social and political forces some of which include:

1. Delay in marriage (Dual incomes missing)

2. A lack of a strong paying full-time job with security.

3. Older Americans are unable to retire due to lack of savings – they replace younger workers, who have trouble finding jobs.

4. Having enough for a down payment plus closing cost with taxes impounded is a lot for young aspiring home buyers.

5. Renting isn’t considered a bad option anymore from young Americans.

6. Exotic loans that allow would be homeowners to obtain credit without collateral or income verification are removed from the market.

7. Financially strapped parents are unable to “gift” down payments for first home purchases by their children.

8. Student loan debt impacted household formation from rising and making it more expensive for first time home buyers to buy.

9. Despite the weak first time buyer market, home prices go up in many markets due to the lack of inventory, keeping home ownership even further out of reach.

This is the result of the Propertarianism posse [“neo-Lockean”] where as “propertarian approach to privacy,” both morally and legally, has ensured Americans’ privacy rights. So on one hand… you have the dominate ideology which dictates all rights stem from C/I/RE [thank you Ayn] – It appears that the term was coined (in its most recent sense, at least) by Edward Cain, in 1963:

… Since [Libertarians’] use of the word “liberty” refers almost exclusively to property, it would be helpful if we had some other word, such as “propertarian,” to describe them. [….] Ayn Rand …. is the closest to what I mean by a propertarian.

And on the other… the propertarians view on wages wrt those that work their “Liberty’s” for them.

Skippy…. reminiscent of old conversations about drunk propertarians in the middle of the day… eh… beardo. Mumbling about giving their sons TTP – TIPP as a gift.

“a positive (in the engineering sense) feedback loop.”

In engineering feedback loops get their energy from an external source, not from the circuit itself. The loop along with the circuit it belongs to is inert.

Otherwise we would have perpetual motion.

The idea of a virtuous cycle in the credit circuit is also pure nonsense. It omits the fact that fiscal expansion is simultaneously generating income necessary for debt service. Take that away and the credit circuit is doomed.

Credit creates more liabilities than assets… i.e. it doesn’t create the funds necessary to pay the interest. This money has to come from somewhere or the liabilities can’t be extinguished (without default).

Credit expansion is limited by income growth in a system where credit accounts for only a fraction of the growth in income.

Soros is just another con man.

I agree with everything you just said except I won’t judge Soros since it’s not worth my time (or risk of being wrong).

Of course, it’s not a virtuous cycle, it’s the boom-bust cycle but it does have its pleasure for a season.

Look at beer. Grains are traded in the futures markets, and mass-market beer is made and sold by publicly traded corporations with executives receiving stock-option compensation. Beer has doubled and/or tripled in price since 2000 ($7 for a sixpack of Bud Light? please).

Grapes are traded on Co-ops all over the world. If there is a glut of grapes, their price goes down. Improvements in technology have made a $8 bottle of wine much better than an $8 bottle of wine in 2000 (Charles Krug doesn’t count), but you haven’t seen a $6 bottle of wine in 2000 go for $12-18 now. Most winemakers are small and privately owned, and they don’t sponsor sporting events. Hmmmm.

Nor are they beholden to their stockholders, the same financiers bidding up prices. Good analogy and yet another benefit of decentralization and a market economy.

Most wine making, or grape production, is done so that the estate owner can call the property a “farm”. This allows big property tax breaks locally, and tax breaks on a federal level.

There are huge outfits in CA that will do all that pesky “farming” type stuff for a property owner, as a contract type deal. Need lower property taxes and some federal tax benefits/subsidies? Call the grape growers, and get into the wine business!

But if grape futures were traded on the COMEX and a whole year’s production of paper grape contracts could be dumped at 3AM (like what happens to gold every week), imaging how cheap (or expensive) wine could be?

Glass for the bottle, the label on the bottle and branding and distribution are all much larger parts of the retail cost of a bottle of wine than the grapes. Even the “cheap” stuff.

Co-op or century old cartel/oligopoly-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Grape_Cooperative_Association

Welch’s. They’ve traveled pretty far from their tea-totaling roots. A lot of their grape production ends up as wine, blended with more “exclusive” grapes. High sugar/alcohol content filler.

In his paper, Pradhananga writes:

The appendix he mentions is a correlation table full of numbers. Increased correlations are shaded red, while decreased ones are unshaded. He didn’t provide an average change in the coefficients (and I’m too lazy to do it).

More troubling to me, as an historical back tester, is that the CRB commodity index dates back to 1956. It’s possible to examine commodity comovement over nearly six decades now. Comparing 1995-2005 to 2006-2012 gives a very restricted picture. Did co-movement fall or rise from 1985-1995 to 1995-2005? The data are available. Commodity honchos such as Geert Rouwenhorst have chomped through them. Cherry picking a brief period when a much longer history is available smacks of tendentiousness.

Doubtless there has been more financialization, as commodities are sought to serve as an asset class that’s relatively uncorrelated to bonds and stocks. In his book Dual Momentum Investing, Gary Antonacci asserts that financialization has changed normal backwardation in commodity prices (future prices less than spot prices) to contango, such that future prices are constantly eroding down to spot levels, thus leeching away expected return.

USCI, a commodity fund advised by Rouwenhorst, reached a fresh low at the end of March. One of these days, comrades, it’s gonna be effed up enough to buy.

I would bet since financialization significantly deepens and broadens derivatives markets, this is the primary mechanism of influence that allows huge agribusinesses to hedge their risks and thereby create and enter global markets — thereby disrupting localized agricultural systems and localized societies.

the correlations among individual commodity returns may reflect financialization or they may not (I think they probly do to a point), but it’s the correlation between financialization and local industry destruction through global agg. that I bet is probably very strong and the primary issue in terms of social breakdowns.

This is a phenomenon in which the financial players ”c” project and magnify themselves through the Money Multiplier Matrix “M” where Mc = Lamda x c, where lamda is the Money Matrix Multiplier distilled down to a scalar eigenvalue. Local Economy “L” has a conditional social utility distribution of 1/M, when L is stable. However the stability of L is often conditioned on the existence and nature of non-monetary M matrices that never the less provide a trampoline for local “c” types to project themselves at the expense of their fellows, citing some mythic relationship to a diety or divine order as the necessary and sufficient condition for their good luck. It’s complicated. That’s why the tatoo on the huge right forearm of the ex-marine machine gunner who hauled garbage in my old high-rise apartment building said “Kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out.” Only somebody like Joseph Conrad can really make sense of this stuff. Math never will.

In the excitement produced by visualizing my ex-porter’s forearm tatoo I totally forgot to type out my other point

This post also offers an indirect illustration of my theory that financial mathematics and models don’t describe reality the way physics equations describe natural reality. Instead the models and equations create a reality that would not have existed otherwise. Real reality shapes itself around the thought forms provided by the models, so the direction of causation is the reverse of what one usually associates with the “scientific method”.

In the distant days of 1972, when trades were conducted in ‘commodity pits’ (seriously!), President Nixon announced price controls to fight inflation. Nobody was sure whether the controls applied to commodity futures. But when grain prices drifted on above the administered prices and nothing happened, all hell broke loose. Grain and all other commodities screamed skyward in 1973, as pit traders chanted ‘Beans in the teens!’

Occurring long before ‘financialization’ was even a buzzword, this concerted commodity spike (whose common element was loss of faith in the dollar) provides a counter-example to Pradhananga’s thesis. But probably he wasn’t even born in 1973.

Normal backwardation (understood in the Keynes’an sense) does not imply a downward sloping term structure of futures prices which is what is generally understood as backwardation in trading circles. Normal backwardation is defined as the current futures price F(t) trading below the expected value of the futures price at expiration E(F(T)) thus offering a risk premium incentivising speculative market participants to provide liquidity to commercial hedgers of production.

With respect to his hypothesis, I would agree that the author is cherrypicking convenient time periods. A vast pool of empirical research that has been done in recent years examining the impact of speculative market participants on commodity price formation has overwhelmingly come to conclusions that do not support the author’s contention. From a theoretical point of view, it is also important to consider that financial participants for the most part never take delivery but roll over exposure, do not engage in physical hoarding and thus do not interfere with price formation in spot markets and convergence of futures prices to spot.

As an example of longer-term analysis, Jodie Gunzberg at S&P’s excellent indexology blog put up a post yesterday, which examines correlation among five commodity sectors (Agriculture, Energy, Industrial Metals, Livestock and Precious Metals) from 1983 through 2014.

Correlations are low between sectors. The post notes that the GSCI sectors debuted in 1991, and had to be backfilled to 1983.

http://www.indexologyblog.com/2015/04/01/commodities-to-be-or-not-to-be-grown/

Her post goes on to note a distinction between ‘commodities to be grown’ and ‘commodities in the ground.’

Some of us would posit a third class, ‘commodities in central bank vaults’ … ah ha ha ha … ‘watch what we do, not what we say.’

I don’t think we should give up on the idea of “economic substitution” quite just yet. If, say, the price of bread gets driven up, the consumer may choose to buy iron ore – couldn’t they?

Additionally, if this is the case, the BLS can say the price of bread didn’t go up. This is a powerful General Theory of Economics which economists can employ to explain our complex world to us!

On our own private farms, we could store large amounts of food, fiber, fuel, etc. and thus be able, in effect, to tell speculators to go stuff themselves (with their hoarded food, for example.)

But the poor can’t afford to think long range and thus we all suffer from poverty – though some think they don’t.

Sure, all we need is Weather Control Technology, then split the country up into little private farms for 300 million Americanskis. Sounds simple enough.

If economies of scale prohibit, say, 100 million private farms, they don’t prohibit the common and equal OWNERSHIP of all agricultural land by all of a country’s citizens via shares.

The state owns everything…. the rest are residual claims… now days sans most responsibility’s…. hence why the public picks up the tab when things go wrong…

Skippy…. Seems you did not take a look at the “read of the day” in the links section… Rwanda event on a continental scale.

I’m reading that the prices of commodities, even gold and silver, fell with the dollar in the financial crash because… world reserve currency. QE then caused mal-investment and speculation and inflation fueled price spikes. Excuse my naivete in the boiling down of what I read to simplistic terms, I’m not even close to being an economist, but it does seem to be what the author is getting at. Anybody else want to boil it down for us layfolk?

I wonder if the ’08 collapse of so many other trading vehicles – stocks, real estate, CDO’s etc – for the hedgies and venture capitalists, prompted their turn to the futures and their associated cash and derivatives markets as a source of returns. Once started, a feeding frenzy ensued, and apparently the CFTC speculative position limits for futures, swaps, etc, that had regulated and prevented speculative excesses for most of its history, had been dialed down for the benefit of ever-rapacious Wall St. funds. It seems to still be a free-for-all. Here is a brief history of the ongoing squabble to again create meaningful limits to speculation in the commodity markets:

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/09/28/us-cftc-positionlimits-idUSBRE88R1C120120928

US | Fri Sep 28, 2012 3:42pm EDT Related: U.S.

Judge throws out CFTC’s position limits rule

WASHINGTON

(Reuters) – A U.S. judge handed an 11th-hour victory to Wall Street’s biggest commodity traders on Friday, knocking back tough new regulations that would have cracked down on speculation in energy, grain and metal markets.

Judge Robert Wilkins of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia threw out the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s new position limits rule, and sent the regulation back to the agency for further consideration.

Wilkins ruled that, by law, the CFTC was required to prove that the position limits in commodity markets are necessary to diminish or prevent excessive speculation.

He also ruled that the amendments to the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial oversight law “do not constitute a clear and unambiguous mandate to set position limits, as the Commission argues.”

The ruling is a major victory to traders just two weeks before parts of the new position limits rule were scheduled to go into effect.

http://www.marketsreformwiki.com/mktreformwiki/index.php/Position_Limits_Regulation

“Section 737 of the Dodd-Frank Act mandated that the CFTC “limit the amount of positions, other than bona fide hedging positions, that may be held by any person with respect to physical commodity futures and option contracts in exempt and agricultural commodities traded on or subject to the rules of a designated contract market (DCM), as appropriate.” [3]

The CFTC reopened the Position Limits Regulation – Comment Letters file a number of times, most recently in December 2014 and February 2015. Its latest comment deadline is March 28, 2015.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/21/business/a-shuffle-of-aluminum-but-to-banks-pure-gold.html?pagewanted=all

Goldman was caught manipulating aluminum… you can imagine what probably goes on with other commodities.

What about oil? Is financial speculation the reason that although crude prices have dropped 45%, while gas prices have only dropped 30%? 15% is a pretty good skim.

Don’t these commodities move with the price of oil?

simpler explanations exist: commodities rose together in 2008 because of the increasing concern over the fate of the US dollar. If the financial system was indeed going to collapse, the best thing to own in that scenario are hard assets, like commodities.

I don’t dispute that financialization of commodities has occurred, Jim Haygood correctly mentions their increasingly popularity as a distinct asset class in his earlier post, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that is the cause of rapid increases in prices. Commodities are probably more “financialized” today than in 2008, yet prices have been falling for months, and those declines aren’t following some dramatic blow-off top just beforehand. WTI crude (the most financialized commodity) was $90-100 for 2 years prior to it’s drop.

Arguably, too much institutional money pouring into long-only commodity funds destroys the roll yield. Now it’s possible to bet against the long-only herd, with a momentum-based fund that tracks a Morningstar long/short commodity index. This is by no means an investment recommendation.

http://www.nuveen.com/CommodityInvestments/Product/Holdings.aspx?fundcode=CTF

As shown in the linked web page, the fund currently is short everything it’s permitted to short: ags, metals, livestock. In the case of energy, it has a short signal, but the rules only permit it to go flat. Shame — the fund would’ve made a ton shorting energy since mid-2014.

Why are we misinterpreting the main frame? More refined, more durable way of seducing is to duplicate, to lather and to curtain. derivatives not a way of mitigating risk but the gilded method for manipulating, cheating and migrating risks to those who are weak and vulnerable.