By Joe Firestone, Ph.D., Managing Director, CEO of the Knowledge Management Consortium International (KMCI), and Director of KMCI’s CKIM Certificate program. He taught political science as the graduate and undergraduate level and blogs regularly at Corrente, Firedoglake and New Economic Perspectives

There are two words that describe the Republicans’ Senate Budget Committee’s proposed budget: “dishonesty” and “austerity” for most Americans. Let’s deal with the dishonesty part first. In due course, the austerity will be apparent.

The Senate Budget Committee’s statement, entitled “A Balanced Budget That Supports Economic Growth and Expands Opportunity for Hardworking Americans,” claims to support stronger economic growth, and provide greater opportunity. We might well ask “how much growth” “growth for whom” and “opportunity for whom?”

Certainly not for me and thee, since the Senate budget projects substantially decreased Federal outlays over the decade 2016 – 2025, compared to the CBO baseline budget. This decreased Federal spending comes from:

– continuously slower growth than the CBO baseline in non-defense discretionary Federal programs (13.2% increase over the decade vs. a 24.2% increase in the baseline); and

– continuously slower growth in mandatory spending (Social Security, Medicare and other health programs, food assistance, unemployment support, other entitlement spending) (33.9% vs. 56.3% for the baseline).

Meanwhile, the Senate plan calls for slightly increased defense spending over the period compared to the baseline (24.4% vs. 23.9% increase).

That’s right with these levels of projected spending we’re looking at austerity for the poor, the young, the aged, and the middle class, since all the programs they benefit from will undergo a continuing squeeze for the Senate’s budget plan.

On the revenue side, the Senate plan, along with the House Budget, projects a 45.3% increase in revenues over the decade, while the CBO baseline projects a 44.5% increase. The difference among these is probably due to rounding and different estimates of how fiscal 2015 comes out before the 2016 – 2025 projection period.

Where does the Senate estimate of tax revenue come from? CBO is the obvious source, and its estimates in turn come from its projections of the recent past and expectations about the impact of scheduled tax increases, which the Republicans in the Senate plan to repeal. The projections of past revenues, along with the impact of scheduled changes in the law, then get applied in the context of CBO’s GDP projections to get to projected revenue. Of course, these can be easily thrown off track if an unexpected recession occurs.

So, projected tax revenues are dependent on and sensitive to CBO projections of GDP. But, future values of GDP, in turn, are greatly influenced by government spending and even more by deficit spending. So, do budgets like the Senate GOP’s that reduce government outlays considerably from the present levels, offer anything else that might grow the economy, and jobs, and increase revenues to the levels claimed in the Senate budget?

Well, the Senate Budget Committee’s majority says that the lower government spending and lighter regulation provided for in their budget will, in addition to the CBO estimate that the baseline budget would add 1 million jobs to the economy, add perhaps as much 1.5 million additional jobs over the 10 year period.

Why? Because reduced regulation and lower government spending creates private sector jobs, of course.

Is this a serious claim? Has it ever worked in the US in recent memory? If so what is the causal chain running from these two things to more jobs that has worked and can be counted on?

The Republicans think that the causal chain works this way. According to “crowding out” theory, an inviolate assumption of CBO ideology, the government borrowing needed for deficit spending dries up limited available funds in “the loanable funds” market. In this way, government borrowing drains off funds that, in its absence, might or would be used for private investment to grow the economy.

This “crowding out” effect isn’t as important in the short run as the effect of government spending in raising aggregate demand. So, in the short run, perhaps the first three years of a decade, larger deficits grow the economy faster than increasingly smaller deficits or balanced budgets would. But in the longer run, the stimulative effects of government deficit spending fade away, and then the “crowding out” effect reduces aggregate demand and slows the economy more than would be the case if there had been no deficit spending in the first place.

The way CBO applied this to the Senate Budget Committee’s plan to reduce deficit spending is that it projects lower levels of economic growth in 2016 – 2018, but then beginning in 2019 it projects increased growth in each year until 2025, with 2025 GDP being 1.5% greater than it would have been under the CBO baseline.

There’s a lot that’s wrong with this fairy tale, CBO or no CBO. First, there’s no loanable funds market. When banks make loans to credit worthy customers, they conclude their loans and create deposits in the accounts of their depositors before they acquire the reserves they need to have according to Federal regulations.

If they find that they are short of the required reserves, then they borrow from other banks in the repo market, or they go to the Federal Reserve discount window to acquire the reserves they need. What they don’t do is to turn down a credit worthy customer because their computer screen tells them that their banks don’t have deposits from private individuals or institutions to underwrite the loan.

Again, they make the loan without any reference to any loanable funds market and get the reserves later, if necessary, from the Federal Reserve which creates the needed reserves “out of thin air.” So, there’s never any shortage of loan funds available because those funds were soaked up previously and made scarce in the private sector by government borrowing from private investors.

Second, even if it were the case that people who wanted to invest in private businesses were holding government bonds, rather than reserves, that would not stop them from making investments if they found a venture that was likely to add to their wealth. This is true because government bonds make excellent collateral for loans from banks creating new deposits which can then be used for investment.

In addition, if the investor doesn’t want to use bonds as collateral, even though they are leverageable multiple times, government bonds are also very liquid. So holders of government bonds can easily sell them to gain liquidity at any time.

Third, CBO and the Senate Budget Committee assume that to run deficits, the government would have to increase its debt subject to the limit. But, under current law this is a matter of choice, since the Treasury is free to fund its deficits using platinum coin seigniorage, a method that would add to the money supply in the amount of the deficit spending involved, and in no way soak up “loanable funds” already out there.

And fourth, even assuming, for the sake of argument, that “crowding out” was true, it still would not follow that lower deficits would add to GDP in the out years more than other budget scenarios that depart from the baseline. For example, what about budgets that compensate for any long-tern effects of “crowding out” by using additional deficit spending to stimulate the economy? If such deficit spending were great enough, then its effect might well be far greater in increasing economic growth than the Senate Budget Committee’s path of decreasing deficits, until in 2025 there is a small surplus of $3 Billion out of a projected GDP of 27.5 Trillion.

I know, I know, some wag will say, at this point, “Well that’s not relevant because CBO only said that the Senate’s budget would increase GDP by roughly $500 Billion over the CBO baseline over the decade of projection.” Well, sure, that’s what CBO always says.

But look, CBO’s baseline is a projection based on current law. The Senate Budget Committee’s assumes changes to current law. So which is more relevant, the comparison of the Senate’s plan to the baseline, or the comparison of other, competing scenarios incorporating policy changes both to the baseline and to the Senate’s plan? Why isn’t CBO required by law to take an objective stance and evaluate competing budgets prominent in the public domain against one another, rather than only evaluating budgets of the majority party against its current law baseline?

Not to put too fine a point on this, a budget plan involving policy changes that only grows the economy by less than 2% of one year’s GDP over a decade, or an average of 0.2% per year is certainly not much of an improvement over current law, and it indicates that the Senate Budget Committee knows very well that there’s not much in their plan that will support growth.

So, why would anyone trumpet that as a promising aspect of one’s scenario? How low must one’s standards be, and how little must one care about economic growth to implicitly ask for political credit for such an unvisionary and unpromising budget plan? And finally, how dishonest must one be to suggest that this kind of growth performance indicates that one’s plan supports economic growth?

Further, if the Senate’s budget were to create the 2.5 million jobs from 2016 – 2025 it claims, then what would be so great about that? That’s about 250,000 jobs per year or about 21,000 per month. The Senate Budget Committee’s report on its budget also claims that the above job creation performance would nearly double the current job creation rate.

So, they want us to believe that 21,000 jobs per month is nearly double the current job creation rate. Where do they live, on Pluto?

Last time I looked, it took 90,000 new jobs per month just to make up for new additions to the labor force, so 2.5 million new jobs in 10 years is pitiful job creation performance. Over the past year our current economy, far from one experiencing full recovery, has still created 2 million new jobs.

The Senate Republicans know this as well as anybody. So, what misbegotten marketing guru advised them to trumpet this projection, and how dishonest is it to claim that 2.5 million new jobs in 10 years is job creation performance worth boasting about as the Senate Budget Committee does? Anyone for 25 million jobs over a decade? How about 35 million jobs? Now that’s something that can be marketed.

35 million new jobs might just create full employment for the 20 million or so who now want full time jobs but can’t find them, and the additional 15 million or so who may be entering the labor force over the decade of projection. But 2.5 million new jobs will fall far short of fulfilling these needs, and representing that low level of job creation as worthy budget job creating performance is just another mark of pure and cynical dishonesty, and contempt for the American people.

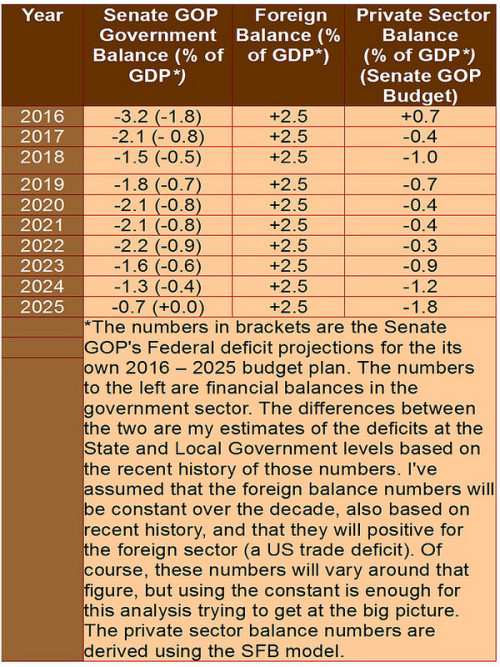

With the above as an introduction to my claims that the Senate Budget plan is both one that would produce increasing austerity, and that is also presented in a highly dishonest manner, I’ll now turn to the question of whether their budget plan is in any way consistent with what is possible under the constraints imposed by the sector financial balances. Once again, I’ve provided a brief introduction to the sector financial balances in an appendix at the end of this post, for the convenience of readers who haven’t used them before. So, now let’s apply the sector financial balances framework to the Senate Republicans’ Federal budget projections from 2016 – 2025, as in Table One, just below.

Table One: Sector Financial Balance Projections 2016 – 2025

The table shows the by now familiar macro pattern of private sector losses found in all the deficit reduction budgets I’ve been reviewing. This one is closest to the pattern found in the Republican House budget.

Assuming a 2.5% current account deficit, and a foreign balance of +2.5%, that leaves a private sector surplus of 0.7% if we apply the SFB model to 2016. That surplus becomes negative in 2017, and after 2017 there are aggregate private sector deficits in every succeeding year through 2025 when there is a private sector deficit of -1.8% of GDP.

The significance of years of these private sector deficits, is that they are likely to hurt private sector balance sheets badly, continuously, and cumulatively, especially those of middle class and poor people, cutting into aggregate demand and the credit worthiness of large swathes of the population. Eventually that will lead to a pull back of credit in the private sector, followed by collapsing demand, declining sales, increased unemployment, recession, and, in the end, expansion of safety net outlays beyond those projected in the Senate budget.

The Senate budget suggests there will be a private sector consistently losing net financial assets, whose expansion is unsustainable. Such losses, due to structural factors of economic influence and power, will be unequally distributed and be borne more by the middle class and the poor, rather than the 1%. This means a consumption downturn and a spiraling of the economy downward.

When that recession happens, the Senate budget will have caused a weaker safety net, and no jobs programs in place to handle the downturn. That also means that even if the Senate budget were passed and was successful in reducing deficits, its drive toward small deficits will cause a pullback in the economy, probably sooner rather than later, and then the remaining government spending automatic stabilizers, though weakened, will still drive up government deficits invalidating its deficit and growth projections, which are, frankly, unbelievable in the absence of a credit bubble to sustain demand. These deficits will accompany an economic pullback causing widespread and growing unemployment once again, and a further need to “fix” the economy.

To conclude, I’ll repeat what I said in my post on the CPC budget. Macroeconomic constraints on budget planning implied by the sectoral balances suggest that if we want to stabilize our economy in a sustainable way, we have to create budget plans that will accommodate private sector desires to both run trade deficits and have a reasonably sized private sector surplus every year. Assuming that 6% of GDP is reasonable for that surplus, and that the private sector would like to import 2.5 – 3.0% of GDP more than it exports, that means that a fiscally responsible budget for the United States, with the right fiscal multipliers, should approximate an annual government deficit of 8.5 – 9.0% in the US’s present situation.

That’s not something we ought to force with fiscal targets, because the best policy is to let the government deficit float and spend on the right programs to produce full employment at a living wage as well as to implement various programs that will solve our many other problems. However, a level of 8.5 – 9.0 percent of GDP is still a rough measure of how far short of what’s needed all the budgets we’ve been examining are.

All of them claim that are fiscally responsible budgets, but judged against what’s needed to solve our various problems, all of them are profoundly fiscally irresponsible. Nor is the level of 8.5 – 9.0 percent I’ve given above necessarily the deficit level that would be produced by a fiscally responsible budget.

Instead the level of the deficit may be greater than this figure if the economy absorbs more deficit spending before it reaches full employment with price stability, as well as other goals. The figure I’ve given above is just a starting place. The deficit should be allowed to float until the real outcomes of fiscal policy we seek are achieved. The measuring stick has to be closeness of approach to these goals, among them full employment and price stability, and not the deficit level per se.

The message is stop targeting deficits! Start targeting real outcomes in the real economy! Start doing budgets that project these real outcomes and don’t focus on the deficit at all, except as a post hoc accounting artifact of the effort to continuously achieve public purpose. That’s what we should be about, not hitting some predetermined balanced budget goal inherited from our long gone gold standard days.

Sector Financial Balances Appendix

The Sector Financial Balances (SFB) model is an accounting identity, and these are always true by definition alone. The SFB model says:

Domestic Private Balance + Domestic Government Balance + Foreign Balance = 0.

The terms refer to balances of flows of financial assets among the three sectors of the economy in any specified period of time. Why must there be flows? Because the three sectors trade financial assets with one another. So, the equation says that the sum of all the balances of flows for the three sectors of the economy is zero, because, since there’s only so much in assets traded in any time period, the positive balance(s) of one or more sectors relative to the others must be matched by the negative balance(s) of the other two sectors.

So, for example, when the annual domestic private sector balance is positive, more financial assets are flowing to that sector, taken as a whole, than it is sending to the other two sectors.

Similarly, when the annual foreign sector balance is positive, more financial assets are being sent to that sector than it is sending to the other two sectors.

And when the annual government sector balance is positive, then it is getting more in financial assets from the other two sectors combined than it is sending to them.

Conversely, when the private sector balance is negative, the private sector is sending more to the other two sectors than it is getting from them, and so on for each of the other two sectors.

Are school districts, local governments and state governments counted under private sector?

It seems that they are run like households.

If money sent to the Treasury is considered destroyed, it’s possible that, for example, when the Pentagon sets up a bank account under its own name, that money is considered private sector money, if we think of that department as a separate corporation, as well as if we consider that that money is no longer at the Treasury (so it is not considered destroyed).

Within a given accounting cycle, accounting rules allow funds to be allocated between departments as management decides. Also what a credit is and what a debit is, varies as to whose ox is being gored (whose balance sheet we are looking at). In all honesty, each micro-balance sheet in an accrual budget will automatically balance … with any net deficit/surplus showing up as some form of finance. A problem ensues as we shift focus to the macro-balance sheet … the problem of governance … which always includes some degree of tyrannical management of the 99% by the 1% … since within a firm, people are agreed as to the model of operation, but not in the case of whole countries or the whole world.

That isn’t the real problem … the real problem is that there isn’t a real balance sheet for the regular economy as a whole, let alone including the dark economy. And thanks to open markets for both goods/services and finance … there are no clear national boundaries. The national economy balance sheet can only balance by borrowing from other nations. Hence neocolonialism. The total economy balance sheet can only balance by borrowing from the future as a whole … hence austerity for present and future generations, because of decisions that are in the past and can’t be reversed. But economics isn’t all numbers, it includes real goods and services, that we are denying the future because of present and past overconsumption … without even mentioning sustainability on a practical level.

It’s important not to get your Sectorial Destroyers mixed up.

The Fed is the Destroyer of Money, the Pentagon invests in Weapons of Mass Destruction – for instance, they may purchase a “Destroyer” for the Navy, which converts money flow to Destruction stock. This appears as an “asset”, both in the sense of government accounting and in the minds of Pentagon officials. These assets have an “useful life”, but your mileage may vary depending on circumstances. They then become fully depreciated, the Pentagon writes them off, and then we need some new ones that the Pentagon will appreciate. This keeps the money flowing. If the money stops, that would be bad.

Hope this makes things more intuitive for you.

+100. And taking it a step further. Acc’d to an RT report the world is transitioning from a neo-colonial world to a post-colonial world. No definitions provided for post-colonial except that those former colonies are now fledging and will be expected to administer their own politics because we don’t wanna do it any more. It’s just too messy. But in terms of the MIC, our perennial and always single biggests budget item, here’s the important bit: in a post colonial world we don’t do hearts and minds any more, we only want your resources. Which is all we ever wanted in the first place, of course. The arc of honesty is long, but actions always prove intent. To mix the metaphor of MLK.

“School districts, local governments and state governments” are counted as part of the public sector, even though they are constrained in their spending because they are users of the currency and not issuers. The Pentagon is also obviously a part of the government whether or not it sets up an account under its own name. We cannot think of the Pentagon as a separate corporation because it is part of the Executive Branch of the Government.

That’s another reason that SFB is irrelevant. Lumping together a currency issuer with currency users offers no guiding principles on budgeting since the two of them have fundamentally different financial positions.

The currency issuer can pay for spending by taxing existing currency units out of existence, imposing user fees or other non tax revenue, or creating new currency units. The currency user can only pay for spending through taxation and user fees.

The SFB model has no relevance to US federal budget choices, though. What matters in public policy at the federal level in our present era is who gets the spending and who pays the taxes, not whether the net difference between total taxation and total spending is plus or minus 2 or 3 or 4 percent of GDP. Inequality is the condition to be addressed (or exacerbated, depending on your perspective).

The SFB model is relevant. To see this just ask yourself whether the pressures of austerity on most people are greater or lesser when the private sector as a whole is losing net financial assets and everyone is scrambling for what s left or for an increased by 10% of GDP pool of net financial assets. Especially given the greater power of the well-off to protect their financial assets it seems obvious to me that for those who are not well off the second situation is much preferable. Also, it seems clear that the history of the US since 1980 also indicates that the development of extreme inequality is associated with private sector surpluses that are increasingly inadequate.

GDP is certainly valuable for limited historical comparisons, but it’s laughably irrelevant when discussing our present system. We have plenty of GDP to go around. Much of our GDP is bad, not good.

The power of the well off to protect their financial assets is in no way diminished by greater flows of currency units from the public sector to the private sector. If anything, the past few decades demonstrates that net transfers from the public to the private sector are quite compatible with concentration of wealth and power. This has been the mechanism of the looting. Bailouts and subsidies and tax breaks for the well connected.

One of the most basic assaults on our system has been the dismantling of progressive income taxation. Taxing the rich would reduce net flows from the public sector to the private sector, but it wouldn’t make things worse. It would make things better.

Sorry, that’s just not consistent with the facts. The development of extreme economic. Inequality has greatly accelerated since the late 1990s.

Before then there were only two quarters when the Household sub-sector balance within the private sector was in deficit, and there were many quarters when the data show that there were surpluses for this sector in excess of 3% of GDP per year.

Beginning in the 2nd quarter of 1999, there is a string of 11 straight quarters when the household sub-sector balance is negative. In the 3rd quarter of 2001 there is a very small positive balance (about .07% of GDP), followed by 29 consecutive quarters of negative household sub-sector balances (deficits). Together, that’s 40 out of 41 negative quarters during that period compared to one negative quarter during the whole history of the United States since 1952.

Now that’s a significant change in the sectoral balances if their ever was one. By and large these years are viewed as good ones for the economy. Certainly better than the 1970s were. But, in these balances we can see the run-up to the Great Financial Crash (GFC) very clearly. Savings in household balance sheets were being destroyed while the credit bubble was creating paper housing sector wealth that evaporated during the GFC.

We can see the pullback starting in the first quarter of 2008 when the household sector turns positive for the first time and stays positive from then on, a period that signifies people doing their best to repair their balance sheets while they reduce exports and the government runs very large deficits, going as high as 11.31% in one quarter of 2009. Of course, these were mostly “bad” deficits created by the automatic stabilizers while after 2009 the Federal Government begins deliberate attempts to shrink the deficit because the “we’re running out of money crowd” is gaining control.” Until now, when w’re running Federal deficits of less than 3% even though the current account deficit has dropped to 2.5% and household balance sheets are not fully repaired.

lol, we don’t have plenty of GDP to go around? How much in your view is enough? Or are you saying taxing the rich has been proven historically to be a bad policy?

Agreed. Inequality was bad in the 1980s and 1990s and has gotten worse in the 2000s and 2010s. Sometimes we have had roughly balanced budgets. Other times we have had enormous net transfers from the public sector to the private sector. For over a dozen years, we have only had net transfers from the public sector to the private sector. So one of three situations exists:

a) Transfers cause increasing inequality, or

b) Transfers can exist alongside increasing inequality, or

c) The transfers to date are not sufficiently large – we need much more massive transfers still.

You are advocating scenario C, a circumstance for which we have no evidence whatsoever since by definition we haven’t tried it. Yet you are saying that my position is the one not consistent with the facts.

You apparently are hoping that I’m some sort of closet balanced budget advocate that will break character or something. I’m not saying balanced budgets are good, and I’m not saying that budget deficits are bad.

I’m pointing out that the historical record is quite clear in post-Bretton Woods America that it doesn’t matter if the Feds run a balanced budget or not. Inequality gets worse. The national security state expands. The drug war goes on. Constitutional rights are shredded. Prisoners are abused. Healthcare gets more expensive. Wages fail to keep up with the cost of living, never mind productivity. Disgusting SUV-based McMansion sprawl grows.

So when pressed on aggregates in the SFB model, you start breaking out sub-sectors? That doesn’t have anything to do with the comment I left. Or the article. You bolded the phrase aggregate private sector deficits, and the appendix doesn’t say anything about sub-sectors.

Because B matters it does not follow that A is irrelevant therefore your argument is logically flawed. Sectoral flows and distribution are seperate issues, both of which must be addressed for broadly shared prosperity.

Agreed. A being irrelevant is what makes A not matter.

Monetarism itself is what I reject. The quantity of money is not the problem. The aggregate flow from the public sector to the private sector is not the problem.

The issue is the distribution of wealth and power within the private sector.

Who’s talking about the quantity of money. I’m talking about the net income in financial assets accruing to the private sector during the current period and the depletion of household balance sheets that is beginning again. I’ve also made the point that the rich are able to better protect their income, during periods of loss for the private sector. So, clearly, I’m talking about macro losses exacerbating inequality.

And, once again, the pattern since the late 90s has been that private sector losses at the macro level is correlated to growing inequality. So, the macro trends are relevant for distributional issues. In addition, I always say that the targeting of deficit spending is very important. We need large government deficits and also targeted deficits that will create full employment at a true living wage and solve other important problems. I am not advocating larger deficits for the purpose of cutting taxes on the wealthy.

Net is a measure of quantity. Are you really nitpicking over this? You write an article talking about the need to increase the difference between spending and taxation, and then don’t want people to say in plain English that you want more flow of funds?

What you have not done is make the case that the rich are not able to better protect their income during periods of gain for the private sector.

No such pattern exists, though. The public sector has been deficit spending for over a dozen straight years, and the surpluses of the late 1990s/early 2000s are so tiny that they disappear when looking at the cumulative net transfer from the public sector to the private sector over the past few decades.

You make it sound like that is just one of multiple variables to consider. I would counter that the targeting is the only thing that matters in our present system. We have enough in aggregate. It’s the targeting that is the problem.

That’s a whole bunch of ands that do not follow from each other. They are separate issues. I think this is the heart of our differing perspectives. You are wanting to solve this at a technical level with a magic principle. I counter that this can only be done by installing good faith management that addresses issues on a case by case basis.

We don’t need large government deficits. You keep trying to link that to other things, but it’s not necessary. There is nothing inherently good about large deficits. It depends upon who is paying the taxes and who is receiving the spending.

And then trying to link that to full employment as if that answers all questions is ridiculous. A JG/ELR/BPSW is a matter of preference, not some kind of scientific law. It is the very thing being critiqued. Saying that I should agree with you because you advocate full employment is not to convince me that I should agree with you. It is to confirm that we do, in fact, possess differing opinions. MMT’s JG advocacy can’t even agree on the definition of living wage, and most of the other important problems JG claims to solve can be more directly addressed by updating the FLSA, SSA, and related legislation to provide for universal health insurance, universal unemployment insurance, a shorter work week, a higher minimum wage, and a higher salary test for exemption from overtime.

So why do you need a larger budget deficit then? Why not just pay for whatever program you have in mind by taxing the wealthy instead of creating even more currency units? Or if you don’t want to raise taxes, cut wasteful spending. There’s a huge amount of unproductive spending, from the TSA to the drug war to healthcare to the military.