Lambert here: I suppose I should be encouraged that mathy economists are being taken down a peg. On the other hand, the new empiricists are only as good as their data and their identification strategies, and, for data, look what happened to Reinhart and Rogoff. And for identification strategies, see the parable of the drunk looking under the streetlight for their keys. Another way of saying this is that mathy economics was useful, until it wasn’t. Now empirical economics will be useful, until it isn’t, although perhaps a bit less imperial in its pretensions, and a lot less crazypants in its model of how humans behave.

By Jérémie Cohen-Setton, a PhD candidate in Economics at U.C. Berkeley and a summer associate intern at Goldman Sachs Global Economic Research. Originally published at Breugel.

What’s at stake: Rather than being unified by the application of the common behavioral model of the rational agent, economists increasingly recognize themselves in the careful application of a common empirical toolkit used to tease out causal relationships, creating a premium for papers that mix a clever identification strategy with access to new data.

Economics imperialism in methods

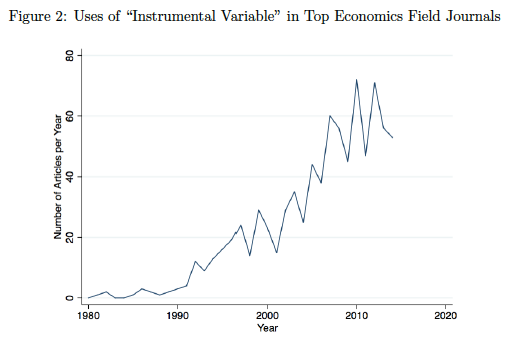

Noah Smith writes that the ground has fundamentally shifted in economics – so much that the whole notion of what “economics” means is undergoing a dramatic change. In the mid-20th century, economics changed from a literary to a mathematical discipline. Now it might be changing from a deductive, philosophical field to an inductive, scientific field. The intricacies of how we imagine the world must work are taking a backseat to the evidence about what is actually happening in the world. Matthew Panhans and John Singleton write that while historians of economics have noted the transition in the character of economic research since the 1970s toward applications, less understood is the shift toward quasi-experimental work.

Matthew Panhans and John Singleton write that the missionary’s Bible is less Mas-Colell and more Mostly Harmless Econometrics. In 1984, George Stigler pondered the “imperialism” of economics. The key evangelists named by Stigler in each mission field, from Ronald Coase and Richard Posner (law) to Robert Fogel (history), Becker (sociology), and James Buchanan (politics), bore University of Chicago connections. Despite the diverse subject matters, what unified the work for Stigler was the application of a common behavioral model. In other words, what made the analyses “economic” was the postulate of rational pursuit of goals. But rather than the application of a behavioral model of purposive goal-seeking, “economic” analysis is increasingly the empirical investigation of causal effects for which the quasi-experimental toolkit is essential.

Nicola Fuchs-Schuendeln and Tarek Alexander Hassan writes that, even in macroeconomics, a growing literature relies on natural experiments to establish causal effects. The “natural” in natural experiments indicates that a researcher did not consciously design the episode to be analyzed, but researchers can nevertheless use it to learn about causal relationships. Whereas the main task of a researcher carrying out a laboratory or field experiment lies in designing it in a way that allows causal inference, the main task of a researcher analyzing a natural experiment lies in arguing that in fact the historical episode under consideration resembles an experiment. To show that the episode under consideration resembles an experiment, identifying valid treatment and control groups, that is, arguing that the treatment is in fact randomly assigned, is crucial.

Source: Nicola Fuchs-Schuendeln and Tarek Alexander Hassan

Data collection, clever identification and trendy topics

Daniel S. Hamermesh writes that top journals are publishing many fewer papers that represent pure theory, regardless of subfield, somewhat less empirical work based on publicly available data sets, and many more empirical studies based on data collected by the author(s) or on laboratory or field experiments. The methodological innovations that have captivated the major journals in the past two decades – experimentation, and obtaining one’s own unusual data to examine causal effects – are unlikely to be any more permanent than was the profession’s fascination with variants of micro theory, growth theory, and publicly avail-able data in the 1960s and 1970s.

Barry Eichengreen writes that, as recently as a couple of decades ago, empirical analysis was informed by relatively small and limited data sets. While older members of the economics establishment continue to debate the merits of competing analytical frameworks, younger economists are bringing to bear important new evidence about how the economy operates. A first approach relies on big data. A second approach relies on new data. Economists are using automated information-retrieval routines, or “bots,” to scrape bits of novel information about economic decisions from the World Wide Web. A third approach employs historical evidence. Working in dusty archives has become easier with the advent of digital photography, mechanical character recognition, and remote data-entry services.

Tyler Cowen writes that top plaudits are won by quality empirical work, but lots of people have good skills. Today, there is thus a premium on a mix of clever ideas — often identification strategies — and access to quality data. Over time, let’s say that data become less scarce, as arguably has been the case in the field of history. Lots of economics researchers might also eventually have access to “Big Data.” Clever identification strategies won’t disappear, but they might become more commonplace. We would then still need a standard for elevating some work as more important or higher quality than other work. Popularity of topic could play an increasingly large role over time, and that is how economics might become more trendy.

Noah Smith (HT Chris Blattman) writes that the biggest winners from this paradigm shift are the public and policymakers as the results of these experiments are often easy enough for them to understand and use. Women in economics also win from this shift towards empirical economics. When theory doesn’t rely on data for confirmation, it often becomes a bullying/shouting contest where women are often disadvantaged. But with quasi-experiments, they can use reality to smack down bullies, as in the sciences. Beyond orthodox theory, another loser from this paradigm shift is heterodox thinking as it is much more theory-dominated than the mainstream and it wasn’t heterodox theory that eclipsed neoclassical theory. It was empirics.

Umm…. Empiric economics [sociopolitical theory in reality]? What the introspective observation to see if humans have uploaded the indoctrination sufficiently or is the narrative glitching.

It takes a huge amount of culture to normalize “crazy”, and of course that’s its main focus. S.Molyneux

S.Molyneux is a mythologist, in another place and time he would be pitching his shtick under a tent whilst constantly on the move.

http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2015-02-12-devolver-honours-molyneuxs-broken-promise-to-curiosity-winner

Skippy… AnCaps make neocons seem coherent, reductive reasoning taken to its most absurd extenuation.

yeaaaah you be right…Stefan is not one of my stronger quote choices (to say the least :/)

shoulda kept it simple: “An economist is an expert who will know tomorrow why the things he predicted yesterday didn’t happen today.”

Laurence J. Peter

Speaking of quotes, I guess this one from Ronald Reagan: “An economist is someone who sees something that works in practice and wonders if it would work in theory.”, will no longer be apropos.

heterodoxy more theory-dominated? Hmm, I think someone has been blinded to own theory-dependence..

The concrete examples given of “a clever identification strategy with access to new data” are the use of instrumental variables and randomization. I will note that both are as liable to be absurd and prejudice-reinforcing as rational-agent modeling.

* Instruments: Acemoglu and Robinson (the Bouvard and Pecuchet of political economy, last spotted measuring the level of countries’ technological innovativion by the number of patents filed in the US), used the mortality rate of Spanish bishops in colonial Spanish America as an “instrument” for the kind of institutions that developed there (and so in all countries post-independence), which in turn explains lower level of economic development in the 19th and 20th centuries relative to the US and Canada. See original and one critique.

* Randomized experiments. Lars P. Sylll is quite skeptical of the claims being made about these for what –to my methods-wimp mind– seem convincing reasons. All I can say from my own experience is that, as we speak, intelligent and well-meaning scholars are deriving some pretty large conclusions about growth and institutions by essentially renting impoverished West African villages so that these can be randomly-assigned to different versions of the “divide-the-dollar” game.

Awewsome. Priors confirmed :-)

The entire field of economics, even the “good” subsections of it, is predicated on a host of common sense cultural assumptions that are only valid, if they are valid at all, in extremely specific sociological contexts. Trying to extrapolate from such limited contextually-specific data, even “empirical” data, Grand Theories of Everything regarding how humans decide to interact with each other is a brain-dead waste of time.

I am deeply suspicious of anyone who wants to engage in this kind of useless navel-gazing–economics–not to mention those who want to employ economists. All I can figure is that since most people are very responsive to arguments from authority, having fake authority figures around to provide academic burnishing for whatever asshole policies elites want to pursue anyway must sure be handy.

Your post makes me wonder if there is a typo in the title, the f’in shift…

Authoritarians do love their false precision.

It’s simple supply and demand, the way I see it. A lot of people want a cushy job as an economist. But society doesn’t actually need that much paid staff activity in this arena, especially since few economists possess the intellectual prowess or novel insight to actually add value to human understanding. So lots of busywork has to be done to try and justify the working conditions and wages of the economics profession.

“I have a paper based on a model based on actual data. Now in return for my gift to humanity, watch my kids, grow my food, build my house, and send me to Vegas and Europe!”

It’s funny, I was hoping that was an exaggeration. Then I googled this:

http://lasvegas2015.iibaconference.org/chair-and-scientific-committee/

One wonders how many of the listed participants and presenters are there with a little kiss from the Koch Foundation, which has been busily perverting academia since 1968 by funding “chairs” and departments and whole universities to fill the intellectual space with Kochisms and products.

Social provisioning is also an interesting part of this. If the goal of economics is to provide for the overall well-being. The neoclassical (non heterodox) method seems to think that via the rational actor we can get there by individual interest.

This neoclassical approach seems to have brought us huge inequality. Feminist, ecological and other heterodox groups want economics to also serve disenfranchised groups and have an eye to sustainability with limited resources.

A few interesting articles on social provisioning are

Expanding Social Protection in Developing Countries by Rania Antonopoulos

http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/expanding-social-protection-in-developing-countries

“This paper discusses social protection initiatives in the context of developing countries and explores the opportunities they present for promoting a gender-equality agenda and women’s empowerment. The paper begins with a brief introduction on the emergence of social protection (SP) and how it is linked to economic and social policy. Next, it reviews the context, concepts, and definitions relevant to SP policies and identifies gender-specific social and economic risks and corresponding SP instruments, drawing on country-level experiences. The thrust of the paper is to explore how SP instruments can help or hinder the process of altering rigid gendered roles, and offers a critical evaluation of SP interventions from the standpoint of women’s inclusion in economic life. Conditional cash transfers and employment guarantee programs are discussed in detail.”

and

The Financial Crisis Viewed from the Perspective of the “Social Costs” Theory by Randy Wray

http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/the-financial-crisis-viewed-from-the-perspective-of-the-social-costs-theory

“At the same time, these trends reduced “social efficiency” of the financial sector, if that is defined along Minskyan lines. Minsky (1992a) always insisted that the role of finance is to promote the “capital development of the economy,” defined as broadly as possible. Minsky would agree with Institutionalists that the definition should include enhancing the social provisioning process, promotion of equality and democracy, and expanding human capabilities. Instead, the financial sector has promoted several different kinds of inequality as it captured a greater proportion of social resources. It has also promoted boom and bust cycles, and proven to be incapable of supporting economic growth and job creation except through the promotion of serial financial bubbles. And, finally, it has imposed huge costs on the rest of society, even in the booms but especially in the crises. “

In my opinion the goal of economics should be to provide a predictable framework on which to compare the outcomes of competing courses of action. How this should be used is a different matter. The framework should stand alone, and not be about well being, human psychology etc.

What sort of outcomes would you be looking for?

Well, there’s always Peter Joseph’s vision (or is it joseph peters?) of eliminating market economies globally. Since economix is just the analysis of markets it would have to look at new forms of consumption. and production. and environmental protection. It’s impossible to imagine economix without markets, isn’t it? No more buying and selling.

tt seems to me that is close to the status today, misreading or ignoring human psychology in favor of one size fits all solutions. how do you place a framework on people who have psycopathic tendencies, for instance. Currently the framework of economics claims to be rational and orderly. It’s been used quite successfully by wall street to fleece the infrastructure of the countries where its viewed as being rational and orderly by allowing wall street to either know generally what people will do, how much suffering will they put up with, using fear as a tool, for instance. This game thrills the bankers and instills a sense of being smarter than everybody else, which is an extremely common psychological condition that, when ignored or reasoned around will lead to inaccurate results.

This is about how a discipline should reach for external truths, not about politics. I’m not at odds with your political vision, but this has to be a different issue to the methods by which truth is sought.

Economics should always have been about assessing what we have – total natural resources of a finite planet plus the ability of the biosphere to absorb humanities waste stream – then balancing that with our sustainable needs.

The problem arrises when we have events which fundamentally change the ledger on one side or another.

Haber-Bosch and synthesizing nitrogen was a major game changer, then the massive exploitation of cheap almost free oil which could be used to overcome nearly every constraint put paid on this simple notion of economics.

Now we have this etherial/all encompassing concept called Tech so there will never again be any constraints to living on this finite planet therefore under these conditiotns ( if you believe all that) economics DOES need to change.

Ignoring the social and environmental downsides leads to collapse, but then it will be too late to “change economics” because all available resources will need to be devoted to adaptation, mitigation, disaster relief, and burying multitudes of the dead.

That is a great observation. I find it interesting how much economists like to blur the discussion of what is happening with what the author would like to make happen.

That article from Professor Wray is a great example. He concludes that market oriented solutions are bad because the social costs of the financial crisis were exacerbated…by control fraud. That is a conclusion clearly driven by a predetermined outcome, not an analysis of what happened. Government sanctioned control fraud is by definition incompatible with a functioning market. It has many other names (fascism, authoritarianism, technocracy, oligarchy, plutocracy, serfdom, neofeudalism, etc.; none of which are markets). Wray can’t have it both ways. Once you acknowledge unprosecuted systemic fraud, the relevant action shifts from markets to public policy. The major development of the past couple decades is that we have injected less “market” into financial institutions, not more. The defining characteristic of a market-based system of political economy is that the government is actively policing the rules.

But Wray has a specific desired policy outcome – he wants a large government jobs program while not being too critical of Fed money printing – so he is naturally inclined to exaggerate market-based problems and minimize governmental shortcomings. Maybe instead of using government to protect financial fraudsters, we should have adopted a more market oriented approach? Put criminals in jail and put insolvent companies in bankruptcy. That’s a functioning market-based system of political economy. But that policy option can’t be debated, or even contemplated, because Wray needs the objective framework (government is good) to match his subjective policy preferences (if some is good, more is better).

Just to clarify Wray’s position on bank fraud

“Exactly. Why isn’t Eric Holder going after the senior executives? Start with Bob Rubin, Hank Paulson, Bryan Moynihan, Ken Lewis, and Jamie Dimon. Seek prison terms on conviction. That would incentivize the banks.”

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/08/update-bank-america-fined-another-16-billion-fraud.html

I’m curious what you were looking to clarify there?

In the 2011 working paper you linked, Wray lays out a very straightforward conclusion:

There’s a problem here. The social costs of not prosecuting banksters don’t come from more market. They come from less market. Government bailouts and backstops are the antithesis of price discovery in private markets.

Now we can argue where more market is valuable and where less market is valuable (there are a whole range of opinions on that front), but to assign a major cost of the ‘less market’ approach to the ‘more market’ side is to fundamentally confuse the actual policy options.

I think you’re getting into the idea of properly regulated private markets. We have private markets that are allowed to function to the point of predation and fraud and then get bailed out.

Wray was also very critical of the bailouts and backstops.

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/rpr_4_13.pdf

“Fourth, the Fed ignored the classical admonition never to accommodate unsound borrowers when it bailed out insolvent Citigroup and AIG. Judging each firm too big and too interconnected to fail, the Fed argued that it had no choice but to aid in their rescue since each formed the hub of a vast network of counterparty credit interrelationships vital to the financial markets, such that the failure of either firm would have brought about the collapse of the entire financial system.

Fed policymakers neglected to notice that Bagehot already had examined this argument and had shown that interconnectedness of debtor-creditor relationships and the associated danger of systemic failure constituted no good reason to bail out insolvent firms.Modern bailout critics take Bagehot one step further, contending that insolvent firms should be allowed to fail and go through receivership, recapitalization, and reorganization.

Although assets will be “marked to market” and revalued to their natural equilibrium levels, nothing real will be lost. The firms’ capital and labor resources as well as their business relationships and specific information on borrowers will still be in place to be put to more effective and less risky uses by their new owners.””

I find it interesting that plain English statements in one document need entirely separate documents to explain themselves.

Professor Wray, in his exuberance to absolve government of responsibility, made a claim that the social costs were caused by markets. That claim is fundamentally inaccurate, no matter how many other 100 page documents he may write.

As a scientist I recognise and welcome these developments. For me the basic flaws in economics are:

1. The reliance on assumptions that aren’t properly tested, the obvious example being that humans are rational actors that maximise utility. Disagreement on assumptions, because they can’t be tested.

2. The use of variables that are poorly defined, e.g. Capital, and which are possibly unmeasurable.

3. An inexperience in the field in how models should be constructed and tested. Eg, how parameters are chosen and understanding their relationship to real things.

4. An over-reliance on reputation as an indicator of quality, partly because of the above. This leads to the ‘big willy’ syndrome highlighted in the article, where he who shouts loudest gets heard most.

1 and 2 would not be tolerated in science, 3 still happens, and 4 to a much lesser extent. The advantage of the experimental approach is that it should be possible to infer hidden variables from observables, and to infer fluxes from outputs. Maturity will come when 3 is resolved. Ideally there is one experiment in which to construct a model and then several more to test it. Ideally in science models FAIL to explain the data, leading to the discovery of important processes previously unknown that affect the phenomenon in question. A classic example of this would be ‘dark matter’, the postulated hidden mass in the universe that could explain why gravitational theory cannot explain the motion of galaxies.

Observation always depends on context and it’s not possible to distinguish sharply between the behavior of the object and it’s interaction with the means of observation. In economics, it seems to be more about posturing the “knowable” as scientific confirmation of behavior from a specific context, then selectively ignoring differences/changes in behavior when viewed from a different context. IMHO, it’s an insidious presupposition that human existence can be neatly compartmentalized while pretending that the essence of existence is “knowable”…humans are not machines, there’s something more and that “something more” always seems to be just beyond the reach of science.

OK I think I agree, but the question is whether these are issues for economics or philosophy. I tend towards the latter.

Consider instead the level of description you wish to apply. You mention human behaviour. Image a physicist deciding that if she can know the behaviour of every molecule in a cell then she can reconstruct a human being, just physiologically, ignoring behaviour. Nobody has ever conducted biology in this way because it is absurdly reductionist and there are better levels at which to come to understanding about the functions of cells, organs and people. Behavioural economics is similarly doomed because the uncertainty in behaviour, multiplied by the number of behaving entities, leads to intractable uncertainty.

Better to start with some observables. at least we can all agree on observables. If we can find relationships among them then we can start to infer cause and effect. This for me is the advantage in the ‘experimental approach’.

You’re mixing apples and oranges: the natural sciences are predicated on the assumption that the natural world is governed by certain fixed and inviolate “natural laws” and that these laws are discoverable through empirical research. The social sciences on the other hand are concerned with studying various aspects of human behaviour, and I’m not aware of anyone willing to defend the proposition that human behaviour is determined by such laws (even if some like the behaviouralists are willing to flirt with such a notion). A research program appropriate to the natural sciences is therefore likely to have limited salience to the social sciences, and demanding that social scientists apply standards appropriate to the natural sciences is likely unreasonable and unachievable.

Now granted, social scientists have brought a lot of this on themselves in their misguided embrace of scientifism in the vain pursuit of prestige and funding, but that’s another topic.

Jabawocky, in a scientific theory, some of the variables used will be undefined, as they must be, for otherwise the theory becomes circular. These are considered to be “primitive” terms, and they may be central. To take a simple case, the terms “line” and “point” are undefined in Euclid’s geometry, although he does attempt to informally explicate the terms so that readers will hopefully understand basically what the theory is about. This does not render the theory untestable when interpreted appropriately.

It is also the case that not all variables are directly measurable. Some must be indirectly measured. This happens often in natural science. It is the theory as a whole which is under test, some parts of which are not directly testable.

Now, I am not advocating this, but the term, “capital”, could by some be used as if it were a primitive term, that is, undefined within the theory. This would necessitate some form of explication of the term in order for readers to all be on the same page. If a term is so vague, however, that it could mean different things to different readers, then such a theory is in serious difficulty.

None of these issues apply to the neoclassical paradigm. The terms are well defined, &c. The fundamental problem with the theory is that it is empirically false and can be shown to be so. And, as has been pointed out, its basic assumptions are so unrealistic as to be laughable. Some of its practitioners thought that its mathematization would render it more scientific, showing a gross lack of understanding of what it is to be scientific, while others thought that mathematization would render the theory politically neutral.

This latter was Samuelson’s position. And he had the example of what had happened to Lorie Tarshis’s textbook as a lesson one should take to heart. And he did. He knew that his position wasn’t truly Keynesian, hence, his invention of a new term, “neoclassical synthesis Keynesianism”, which Joan Robinson called “bastard Keynesianism”. This hybrid was the paradigm that prevailed after WW2 until the seventies when this paradigm kind of morphed into the neoclassical paradigm, which rather quickly became the dominant paradigm almost everywhere.

There’s a lot of things that bother decent ordinary people about “economics,” including the screwing we get at the hands of people animated by greed and short-sighted stupidity using the “tools of the economist tools” to ‘splain why what they want to do to others, reaping the profits and shedding the externalities and losses, is just part of the Great Natural Order.

financial matters, above, asks jabawocky “what sort of outcomes would you be looking for?” Ordinary people are excluded, by the way power is concentrated in the world the way it currently is, from having any voice in saying what the goals and outcomes “ought” to be. jabawocky would divorce, like the “echononomists” presume to do, “a predictable [sic] framework on which to compare the outcomes of competing courses of action,” from the human consequences of the applications of that supposedly-possible-to-denominate, so-far-fraudulently-bruited “framework:” “How this should be used is a different matter. The framework should stand alone, and not be about well being, human psychology etc.” That, sir, is convenient tripe.

So “we” are left with “might maketh right,” the apotheosis of the “libertarian” fallacy, and the facile ability to pervert and suborn all the institutions that provide any hope of the reduction of pain and horror in the world, or motions toward a sustainable presence for our sorry plague-organism species on the only planet we currently infest.

And our collective sum of infatuations and affections with technology, coupled with whatever it is that motivates the people of ISIS and other successful business models like Monsanto and Goldman Sachs and Lockheed Martin, keep increasing our asymmetric vulnerabilities, huge numbers of people with little lives that are bled of wealth and value and meaning so a very few can do what, again? We little people go along, shoulders to the wheels, re-filling the pipelines of real wealth after each enormous bleeding by “crisis” and war and other faults, largely oblivious to the details of that ever-increasing vulnerability, to collapsing habitability, to weapons and the institutions that deploy them, to their lives reduced to manipulated data sets pending some cyber-collapse.

One more little thing that “echononomics” doesn’t account for is what I think of as “scale.” The Winners, so far, are bound like the rest of us to life spans that are relatively short compared to the duration, so far, of the species. (Though if wealth applied to science can unlock the Secret Wisdom of Cells, the Few will get either vastly extended time to continue their predations, or maybe essential immortality — lots of science fiction has speculated on what that division might mean.) That “Apres moi le deluge” ethos, IBG-YBG, seems inevitably and inexorably to lead to ever grander waves of hierarchy and concentration and profligacy of resources and disposability of others’ lives and “well being,” for the short-term pleasure of a very few — who get to burn so brightly, like the Sun-King, torching everything around them, and then wink out, in the greatest comfort after the indulgence of the hugest piles of personal pleasure, unaccountable after a gentle death with the best of care. beyond restraint when in full taking mode, beyond retribution when dead. So little humans, does not matter how big the ego or the “net worth,” with short-term greed as their driver, not giving a rat’s patoot about the rest of us who by our labors make their personal apotheosis even possible, get to “decide” the fates of billions, and the biosphere…

So indeed, great question: “What kind of outcomes are you looking for?” It’s a question that kind of gets hinted at in various posts here, with a tacit answer that I sense is mostly just “(a) protect my gains, and my middle-upper-class position, with (b) a smidgen for distressed others if that does not impair my (a).” If there is enough of Maslow’s necessities to go around, for all nearly 8 billion of us, which is an examination that one would think “economists” should join with other disciplines to find an honest accounting of, then if we can develop an ethos that points to survival of the species, ours and all the others, and a long-tern sustainable “political economy-ecology,” what are the elements and institutions and “parameters” that would make up that “paradigm?”

Glad to see that Goldman is back, big time, in the high-speed trading business, and Ukraine and Israel and Uganda are all on the move too…

financial matters’ question is The Question. What outcomes are we looking for? Here on NC we all talk about this every day. More in the context of how wrong and screwed up things are and less in the context of what do we want and where do we start. I’d like to get rid of banking all together – but how on earth can we do it?

susan, that’s a frustration I share with you. “Sharpen the contradictions?” Not too effective in a mindscape where what should be intolerably painful levels of cognitive dissonance are so very patent. It’s a Hydra kind of problem, though hugely bigger and with a lot more heads, and there’s no Herakles to take a sword and a torch to the beast — our “heroes” are more interested in feeding it…

One wonders if Funny Munny at some point extinguishes itself, zeroes out, when the Real Wealth that it leverages off of gets what — also zeroed out, with calamity and catastrophe? We refer to “banks,” but of course that’s a word that has changed its contours and meaning so very irretrievably since the days when a bank was a stone building with a massive colonnade and gold leaf lettering on the windows and doors and a big old vault with a time lock and sour-faced clerks and “vice presidents” presiding over your “savings” and discouraging any unthrifty behavior like borrowing money.

One wonders — will the effing Obamites and the supranational “business” interests lose a big round in the effort to vitiate all that annoying local sovereignty that sometimes makes their minions have to break a tiny sweat to ensure the corporate “right” to do whatever their notions of profit and gain lead them toward in this fiscal quarter? If our rump Congress, for such a congeries of reasons, fails to give the bastards the keys to the kingdom this month, will something develop out of that where “the people” start to see a parallelism of interests in stopping the Oligarchicalization of Everything? Seems to me that “smallness” and appropriate scaling is a big part of any kind of change for the better, as you and I might value that notion…

One could hope for some kind of masochistic systemic collapse, too, where Skynet goes off the rails…

Look, i too share your concerns about the world and agree that we need a vision when it comes to outcomes. Can i offer this vision, who knows…. Perhaps we need a whole thread on this, proactive instead of the usual reactive stuff.

That said, I will defend what JTMcPhee calls my ‘tripe’. Economics as a discipline must be divorced from outcomes. Are there universal truths to be discovered, such as Piketty’s belief in growth/capital return relationships? Are these about selecting outcomes? No, they are about describing outcomes. Lets be clear this is already a major challenge.

Then comes the question which outcomes are acceptable? This is worth broaching only once we agree what the outcomes of any course of action would be. The current state of confusion results in part from confounding the two questions.

Looks to me like chicken egg, cart horse. We all have our mental frames.

Seems to me that “outcomes” for the people who dig and carry and fix and treat and teach and comfort fall into a pretty predictable range of preferences: for enough to eat, clean water to drink and air to breathe, security against overbearing potentates, community that operates on comity.

Sounds to me like erecting a framework that “evaluates possible outcomes” up in the rarified air of “discipline” inevitably installs the biases of the kinds of thinking that produce the outcomes “we” suffer from now — the notion of the purity and sanctity of the “free market,” the beliefs about individual choice, the “efficiency” of everything tested and measured, “substitution” displacing satisfaction, crapification and cheapening of everything that is reduced to a monetized, rentable “product.” And the Great USian Business Model: more and more work from fewer and fewer people for less and less pay and greater and greater wealth disparity, along with Ritz crackers that come 40 fewer to the box for the same price and 1/8 inch less in diameter, and a “half gallon” of orange juice that consists of 59, not 64, ounces, and the “6 ounce” can of tuna fish that contains maybe 3 1/2 ounces (and of course is labeled to mislead us misbegotten “consumers” but avoid sanctions if there ever was any enforcement by “the government.” And on and on, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vbKeBoneyDk. Because consumers are suckers, the regulatory processes are owned by “business,” there are no remedies in the “law,” and ‘equilibrium price.’

There is no way I can see to actually, honestly, approach “economics” without doing “political economy.” The idea that selection of outcomes for “acceptability” only comes after the ‘disciplining’ by people who are known shills and frauds for one set of interests, and stack and direct all the “framing” and data choices and modeling, with occasional exceptions like maybe Piketty?

Universal truths? Which ones are you talking about? Please — lay out what universal truths “economics” is supposed to uncover and explain. All this stuff is about relationships, that flow from accidents of the location of “natural resources” and other elements of what was sort of thought of by ancients (as far as we can tell) as a “commons.” One “universal truth” that I read about in economics texts is that “there’s no free lunch,” which is maybe thermodynamically true, but where humans are involved,with their squishy emotions like altruism and kindness and pity, not so much. And another is that “the commons,” as us DFHs understand the term, is just a myth. Though the “enclosing” and exploitation of “commons,” all over the planet, was and is an “outcome” approved by ‘economists” as “more efficient” and ‘market.’ Seems more like a question of who has the raw power to TAKE way more than a living, decent share.

Really, please explain what your understanding of the discipline of economics entails, and how practitioners divorce their cogitating about models from pre-determining or at least leaning, consciously or not, influenced by the preferences of patrons or not, divorce that thing you call “discipline” from “outcomes.” I guess I just don’t see it — any more than philosophers can do anything useful for the species and the universe by positing grand constructs about Universal Truth and Reality without reference to toe fungus and leaky roofs and public executions and the way humans combine to f__k each other over. Please explain? I’m sure there is more than just a soaring, comforting (to some people) assertion behind the notion…

“Mostly Harmless Econometrics?”

AKA Taylorism.

The issue is who gets to decide what is harmless or not.

Looks like this is “Scholars in Search of a Topic” material. Strange that the story below appeared on the internet on the same day as this post. What a coincidence!

Scholars in Search of a Topic

by D. Tremens, reporter at large

Worldwide News Press

June 16 — In these august ivy covered halls where knowledge soars to the sky in flaming rockets of scholarly erudition economists once strode flourescent hallways like giants of the mind. But today a crisis engulfs this once prestigious discipline. Economists don’t know what to do anymore. Decades of economic theory has been discredited by one crisis after another. Not only were economists’ best predictions no better than dart throws but even the fundamental tenets of the discipline were revealed by common sense to be preposterous.

“It’s a crisis all right”, said Harvard economic Professor Felicia Futill, “we’ve realized people aren’t rational and there’s no such thing as equilbirium. All our most cherished notions of economic reality are on the trash heap. Nobody knows what to do.”

Some economists are fighting back by extending the borders of the discipline. One is MIT economist Ed Bucks, who is studying the grazing patterns of herds of deer for insights into how market actors make decisions under constraints of both scarcity and information. “Deer don’t know where the best grazing areas are in a forest,” said Professor Bucks to a reporter, “and when they find them they usually eat everything in sight. That’s a lot like people.” Professor Bucks used to sit in an office staring all day at mathematical equations but now spends his days sitting in a tree watching deer through binoculars. “It’s better than an office. unless it’s raining” he said.

Once cherished notions such as utility maximization are now in disrepute. “Usually people screw things up,” said Professor Futill. “I don’t know why we ever believed in utility maximization, unless people are trying to destroy themselves. It’s nonsense and I’m glad I see it now for what it is.”

Equlibrium is another once vaunted tenet of the economic cannon now on the ropes. One new sceptic is University of Chicago professor Newt Newton. Professor Newton once used equations to prove equlibrium conditions organize markets without government intervention. Now, he uses math to prove the opposite. “I changed my mind”, he said. “I don’t even know why I used to believe it. What I used to prove with math I can now prove the opposite with the same equations and I can’t tell the difference. Thank God I have tenure or I’d be in trouble.”

Christ Converts To Islam The Onion. “I was wrong, and I know that now,” He added. “I deeply regret any problems or confusion I may have caused.”

Too bad that political economy is not as, ah, discrete as operating system coding. Then the species might benefit from the efforts of someone like Linus “LINUX” Torvalds:

The Creator of Linux on the Future Without Him

Linus Torvalds is the creator and sole arbiter of the Linux operating system, which is used in everything from Google servers to rockets.

The conversation, combined with Linus Torvalds’s aggression behind the wheel, makes this sunny afternoon drive suddenly feel all too serious. Torvalds—the grand ruler of all geeks—does not drive like a geek. He plasters his foot to the pedal of a yellow Mercedes convertible with its “DAD OF 3” license plate as we rip around a corner on a Portland, Ore., freeway. My body smears across the passenger door. “There is no concrete plan of action if I die,” Torvalds yells to me over the wind and the traffic. “But that would have been a bigger deal 10 or 15 years ago. People would have panicked. Now I think they’d work everything out in a couple of months.”

It’s a morbid but important discussion. Torvalds released the Linux operating system from his college dorm room in Finland in 1991. Since then, the software has taken over the world. Huge swaths of the Internet—including the servers of Google, Amazon.com, and Facebook—run on Linux. More than a billion Android smartphones and tablets run on Linux, as do billions upon billions of everything from appliances and medical devices right on up to cars and rockets. While Linux is open-source, which allows people to change it as they please, Torvalds remains the lone official arbiter of the software, guiding how Linux evolves. When it comes to the software that runs just about everything, Torvalds is The Decider.

What’s more, Torvalds may be the most influential individual economic force of the past 20 years. He didn’t invent open-source software, but through Linux he unleashed the full power of the idea. Torvalds has proven that open-source software can be quicker to build, better, and more popular than proprietary products. The result of all this is that open-source software has overtaken proprietary code as the standard for new products, and the price of software overall has plummeted. Torvalds has, in effect, been as instrumental in retooling the production lines of the modern economy as Henry Ford was 100 years earlier.

It’s absurd that so much power has collected in one man. To look and speak with Torvalds is to not expect much. He’s 5-feet, ho-hum tall with a paunch, John Lennon-style round glasses, and gleaming, square-shaped teeth. It’s cheap and easy but true to say his body type and gait resemble that of Tux, the penguin mascot of Linux. Torvalds works at home, and during his busiest times—preparing a new version of Linux for release—he might stay inside for a whole week. “It embarrasses my daughters,” he says. “I’ll show up in the kitchen in a bathrobe, and her friends will ask, ‘What kind of hobo is your dad?’”

In the early days of Linux, proprietary software giants such as IBM and Microsoft scoffed at the idea of this man and his hobbyist code accomplishing much. As Linux’s popularity soared, their tune changed. IBM and others embraced Linux. Microsoft likened it to cancer and portrayed open-source software as an affront to capitalism. Torvalds was then made out to be the socialist software activist from Finland threatening the huge profits of the software industry earned honestly in the U.S. of A.

The truth is that Torvalds has never really been a man of the people. “It’s not that you do open-source because it is somehow morally the right thing to do,” he says. “It’s because it allows you to do a better job. I find people who think open-source is anti-capitalism to be kind of naive and slightly stupid.”…

Given all the uses and abuses to which “code” is put, and its pervasive presence, and the presence of people who will happily and grimly and seriously develop and deploy STUXNET and all those “grab it all” active entities and back doors that Hoover up all the moments and evidence of our lives, “steal our identities” (as if our tiny bits of the bitstream are the sum of our lives, are “us,”) and Anonymous and even less innocuous hackers, one wonders if there’s a similar individual who can shut down all the invasive, intrusive, toxic, destructive, idiotic “apps” that plague us. Or would, if he or she could. Then I remember all the behaviors I’ve witnessed myself, in my own little lifetime, or via the wackiness of Youtube, and think, is any of all that worth lifting a finger to try to “make better?” Would any of the people exposed by all that, players of “Grand Theft Auto” and “Call of Duty” and “Game of War,” lovers of “Game of Thrones,” willing joiners into the “drone phenomenon,” be aware of or grateful or anything but angry and annoyed by any efforts to make their “outcomes” what I would consider “Better?”

Empirical investigators of the economy should include forensic accounting and criminology in their preparatory studies. And they should probably should consider including double indemnity life insurance and accidental death and dismemberment insurance in their personal financial plans.