Yves here. I was originally merely going to refer to this article in my piece in Greece this evening, but I thought it merited posting as a separate post, particularly since VoxEU is read by policy wonks in Europe and thus may influence calculations about how to respond to continued Greek defiance to implementing contested structural reforms, or what Greeks call “the memorandum” and Eurocrats call “conditionality” (as in conditions attached to the IMF rescues).

Also keep in mind that this post plays on a distinction that is often lost in press coverage of Greece: that a default does not imply a Grexit. Syriza promised no Grexit, and most polls in Greece have shown considerable opposition to leaving the Eurozone. While a Grexit is possible, the most likely route would be via the ECB shooting the Greek banking system in the head by refusing to provide needed funds through the ELA. Informed observers maintain that the ECB would not take such a drastic measure unless it had ample political cover. While hardliners like Wolfgang Schauble and some of the more hawkish members of the ECB board maintain that the Eurozone could handle a Grexit, plenty of others, most important Merkel, are opposed (the belief re Merkel is not so much that she views a Grexit as necessarily a disaster for the Eurozone, but that it would be a big blot on her legacy).

By Jeffrey Chwieroth, Professor of International Political Economy in the Department of International Relations and a research associate of the Systemic Risk Centre, LSE and Cohen R. Simpson, Doctoral Candidate in Social Research Methods, LSE. Originally published at VoxEU

Many fear that a Greek default would lead voters elsewhere in Europe to favour default over austerity. In contrast, this column argues that it is more likely to have the opposite effect. Network interdependencies among countries affect domestic politics of default because of the rareness of vividness of default to voters. Foreign default increases the propensity for voters to punish their own governments for failing to repay external private creditors. Therefore, there are lower political incentives for default at home.

Governments in Ireland, Portugal, and Spain have adopted a conspicuously hard line stance in negotiations with the new Greek government, partly out of concern that a Greek default would strengthen anti-austerity parties at home (Wyplosz 2015).1 How do we know if a default would have such an effect? Since most of the academic literature on the politics of debt default overlooks political and economic interdependence, it is not of much help in answering this question (Jackson et al. 2015). Our new research starts with the simple premise that interdependencies among different countries in economic networks are likely to have a profound impact on the politics of default (Chwieroth et al. 2015). Specifically, we provide evidence that foreign defaults tend to increase the propensity of voters to punish their own governments for failing to repay external private creditors.

Ultimately, our results suggest that a Greek default would be more likely to lower rather than to raise the political incentives for other European governments to default, contrary to the expectations of many commentators and political leaders.

Default and Political Survival

A standard argument is that a government’s willingness to repay its debts will in general be much more important in shaping decisions than its ability to repay (Eaton and Gersovitz 1981, Reinhart and Rogoff 2009, ch.4, Tomz 2007). If so, voters will plausibly view default as an exercise of political choice. Most studies agree that defaulting governments in democratic polities experience a significantly heightened risk of loss of office – one reason why default is rare in democracies (Borensztein and Panizza 2009, McGillivray and Smith 2008, Livshits et al. 2014).

On the other hand, scholars have argued that elected incumbent governments may nonetheless choose default for various reasons:

• Public sector employees, pensioners, low-income and unemployed voters are numerous and favour prioritising short-term domestic transfers over repayments to creditors (Saiegh 2005);

• Voters believe creditors will be more forgiving in demonstrably hard times or cannot effectively sanction defaulters (Borenzstein and Panizza 2009, Bulow and Rogoff 1989, Tomz 2007);

• Domestic political institutions discourage creditor coalitions (Saiegh 2005, 2009, Stasavage 2003); or

• Foreign creditors can easily be cast as unreasonable and rapacious (Broner et al. 2010, Gelpern and Setser 2004, Reinhart and Rogoff 2011, Sturzenegger and Zettlemeyer 2007, Tomz and Wright 2013).

The continuous re-election of Argentina’s ruling Peronists since 2001, the success of Syriza in the January elections in Greece, and the Greek government’s behaviour since then are recent examples of the role these factors play in the survival of incumbent political parties in the context of actual or near-default.

How International Networks Matter

While most of this literature assumes that the politics of default in different countries are effectively independent, studies have shown that the international context matters for the domestic vote (Duch and Stevenson 2008, Hellwig 2001, Hellwig and Samuels 2007, Kayser and Peress 2012). From a network perspective, two alternative possibilities arise – networked default either reduces or increases the propensity of voters to punish incumbents for failure to repay.2

Most of the literature on economic voting implies that networked default will reduce the propensity of voters to punish incumbents for default because it will indicate to voters that default is more ‘excusable’ due to exogenous shocks beyond the government’s control (Alesina and Rosenthal 1995, Duch and Stevenson 2008, Hellwig 2001, Hellwig and Samuels 2007, Kayser and Peress 2012, Persson and Tabellini 1990, Scheve 2004, on excusable default see Grossman and Van Huyck 1988).3

However, we think that this proposition is less applicable because default is both complex and rare. Excluding countries that have never defaulted, the average number of years between defaults among independent democracies in our dataset is 42 years over 1870-2009, making default on average a more or less once-in-a-lifetime experience for individual voters. By comparison, the US economy experienced a recession every 4.8 years over this period.4 The inexperience of voters with default will make it unusually difficult for them to assess its likely consequences, thus increasing the salience and perceived value of information provided by networked default. Rareness also enhances vividness, predisposing voters to weigh such events and their (presumed) consequences highly when assessing the competence of political incumbents and the likely effects of national default (Kahneman et al. 1982).

Default also typically entails significant short-run costs, including large output losses, lower credit ratings, higher interest rate spreads, a decline in trade and trade credit, and a heightened risk of a banking crisis (Borensztein and Panizza 2009, De Paoli et al. 2006). Networked default also tends to occur in difficult global economic times. Thus, networked default will highlight the costs of default to voters, increasing their anxiety about default at home. Voters may also be sensitive to the argument that repayment in the context of networked default will constitute a helpful reputational counterpoint for their own country. Since 2010, the UK Conservative Party successfully used the Greek example to reinforce political support for fiscal austerity.

In light of such costs and the inherent rareness of default, networked default should thus increase the risk that national default will incur voter punishment. Our research illustrates the importance of this effect using historical examples from Australia in the 1930s and Venezuela in the early 1980s. In both cases, incumbent governments faced significant exposure to default in their respective networks. In Australia, voters repeatedly rewarded a United Australia Party government for honouring its onerous repayment obligations via severe austerity at home. In Venezuela, by contrast, the incumbent Christian Democratic government suffered an avoidable default and in 1983 experienced the most severe election loss in the country’s postwar history.

Empirical Findings

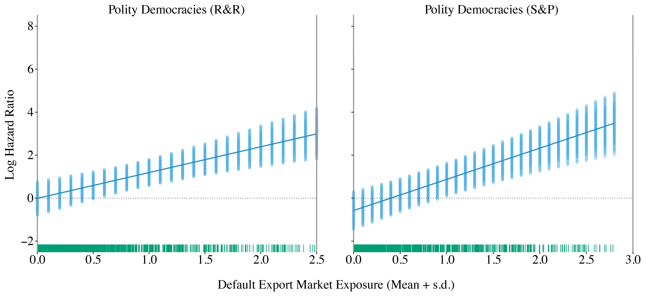

Our quantitative results for democracies over the period 1870-2009 support our expectations. We use a Partisan spells indicator to measure when incumbent political parties lost office, allowing us to compare results across different democratic systems.5 Our measures of default are taken from Reinhart and Rogoff (2009) and Standard & Poors (2013), and include all instances of a failure of a government to fulfil ex ante obligations to external private creditors in the first year of default.6 For reasons of data availability and because trade ties will be relatively tangible and visible to voters, we use the share of a country’s total exports in a given year which go to defaulting countries to measure each country’s yearly networked default exposure.7

We use this network variable and our measures of default to create an interaction term in a series of Cox proportional hazard models to assess the conditional effect of default across varying levels of default export market exposure on the expected rate of incumbency survival.8 Figure 1 plots the marginal effect for defaulters as default export market exposure varies from its observed minimum to one standard deviation above the mean (the median line summarises the central tendency from the simulations). The magnitude of this effect is large. A government with relatively high exposure to networked default is approximately ten times more likely to suffer a partisan spell termination than one with low exposure.9 These results are consistent with our argument that networked default negatively frames voter evaluations of national default, making them more likely to punish incumbents who replicate foreign misbehaviour.

Figure 1. Marginal effect of sovereign default conditional on default export market exposure – R&R and S&P defaults in polity democracies

Note: The ribbon represents the middle 95% of 1,000 simulations and the density of the ribbon indicates the set of values with the highest probability. We also include a rug plot of the distribution of the Default Export Market Exposure variable.

Implications

Our findings provide systematic evidence that, contrary to fear that a Greek default would lead voters elsewhere in Europe to favour default over austerity, it is more likely to have the opposite effect. A substantial Greek default would be highly chaotic and costly (at least in the short run), vividly framing default for foreign voters as something to be avoided rather than replicated, not least given the signs of recent recovery elsewhere. It would also likely highlight the potential advantages of debt repayment as a counterpoint to Greek misbehaviour. Economic misbehaviour elsewhere in an international network appears to reinforce the tendency of voters to eject leaders who also misbehave when facing severe financial shocks. Of course, political leaders could still misread voter preferences and default anyway. As the Venezuelan case demonstrates, they would do so at their peril.

Footnotes

1 Phillip Stevens, “How politics will seal the fate of Greece,” Financial Times, 21 May 2015; Gideon Rachman, “Europe cannot agree to write off Greece’s debts,” Financial Times, 26 January 2015; Wolfgang Münchau, “Eurozone’s weakest link is the voters,” Financial Times, 29 December 2014.

2 We define networked default as the degree to which default is prevalent amongst those countries with which a focal country is directly tied.

3 Networked default might also erode a social taboo against misbehaviour, making it easier to do (Friedkin 2001).

4 Default averages calculated using Reinhart and Rogoff (2009); US business cycle data from http://www.nber.org/cycles.html (accessed 27 April 2015).

5 Democracy is defined as years in which the Polity IV measure exceeds five for the full incumbent spell.

6 The R&R and S&P measures each yield 36 defaults in democracies over the whole period. The R&R sample of 56 democracies indicates 28 out of 561 partisan spells (5%) experienced default. The far more complete S&P sample of 99 democracies indicates 30 out of 709 partisan spells (4%) experienced default.

7 We also explored other country ties based on common region, language, religion, and joint membership in international organisations. However, we failed to uncover any significant effect.

8 Our control variables are the degree of democracy, age of the democracy, economic growth, global economic growth, GDP per capita, export receipts, and past default history using the cumulative number of defaults and the number of years since a country’s previous default. We also control for systemic variables (global GDP growth and export receipts) as a way of trying to isolate the causal mechanism we identify.

9 ‘High’/’low’ values of the default export market exposure variable correspond to one standard deviation above/below the mean in the R&R dataset.

See original post for references

I think Tsipras has a much better handle on the political situation than this attempt to analyze a default with ‘a series of Cox proportional hazard models’. Also this article gets into social taboos of misbehaving by not repaying loans rather than examining the predatory nature of the loans.

From Tsipras’ LeMonde oped:

“”My conclusion, therefore, is that the issue of Greece does not only concern Greece; rather, it is the very epicenter of conflict between two diametrically opposing strategies concerning the future of European unification.

The first strategy aims to deepen European unification in the context of equality and solidarity between its people and citizens.””

This is a somewhat cynical point of view, but I find it difficult to have any confidence in a report that references democracy in the EU countries. In the United States we have any number of examples where the “will of the people” is clearly expressed and very definitely ignored – if it is reported at all.

In Europe, as I remember, the people have clearly expressed their opinion on a number of occasions, and their governments have caved in to austerity.

It’s probably not very “scientific”, but I believe that the only way to find out the true reaction of the people to a Greek default is for that default to actually occur.

“Default is punished by the voter dismissing the Government.”

That matters little.

What’s next for the Greeks? If austerity wins in Greece because of the collapse of the Government, then the citizens of Greece descend into starvation quickly?

That would provide what, an example for the others in the EU to descend into starvation slowly, instead of quickly?

Desperate staving people do what? Lay down and die?

This reads as if you are shooting the messenger. You can’t rebut the conclusion but nevertheless feel compelled to disagree.

It’s far from clear that dismissing the Government is an effective or meaningful punishment in any case, given the steady decline in average policy outcomes and living standards independent of elections.

Also note the lack of agency: “Default is punished” by whom, through what proxy(ies), and to whose ultimate ends?

I believe that’s the desired outcome.

Claiming a default constitutes one by a sovereign government is a bit of a stretch. The EU has to take up some of the blame, as they hold the keys to the printing press.

Tsipras always has had the option of recognizing that he had signed an agreement in February that reaffirmed the existing memorandum, as in structural reforms, and that he needed to stick with the program if he wanted to get the now desperately needed bailout funds. The choice of default or no default is firmly in the Greek government’s hands. You may decry the economically destructive policies of the creditors and the way that French and German banks were bailed out by laundering the money through Greece, but it will clearly have been Greece’s choice, not the creditors’, if Greece defaults.

Except that it is clearly NOT in Greek hands Yves! How can Greece avoid default? By agreeing to Troika demands? They cannot do that without causing a split in Syriza and a vote of no confidence in the government.

How did we get here after all? Because PASOK could not deliver on carrying out the Memorandum. No other political party can do it either. How much did PASOK and it’s successors like Olive Tree get in the last election? That’s the measure of public support for continuing the Austerity program. The Troika simply wants Greece to ram it through, despite the overwhelming rejection of these proposals by the Greek people and it simply cannot be done. By anybody.

Even if they were somehow able to continue the Austerity program, thereby gaining more bailout funding, the economy will only continue to collapse, leading to greater and greater deficits.

Hence default is unavoidable. So, it is NOT within the power of the Greek government to avoid default no matter what they do.

Unclear why NC readers don’t seem to acknowledge the obvious – Greece has in reality defaulted a while ago. When then only way they’ve been able to make continued payments on their debt is continued infusions of cash from elsewhere – i.e. to go further into debt – that IS a default by any rational measure. Austerity has had the predictable effect of lowering GDP which leaves Greece less able to service their debt. Yet somehow the EU believes that more austerity – lowering their GDP further while in the meantime giving them more money – further increasing their debt – will eventually lead to a place where Greece can pay the money back? Where is there an example where doubling down on failed policies leads to success? The Emperor is naked and has been for a while.

You miss completely that this fight is about structural reforms. Greece has already had restructurings that lowered the economic value of the debt considerably by extending maturities, lowering interest rates, and deferring interest payments. Before the negotiations got ugly, every informed expert I spoke to said the creditors fully expected they’d have to lower the amount of the debt further in economic terms. They don’t want to reduce the face amount, which is why you get all kinds of misleading reporting: “Greeces’s debt is 330% of GDP!” While technically accurate, the economic value is MUCH MUCH lower even now.

But Greece stil can’t service even that actually lower amount of debt (and all a government has to do is service debt) if its economy continues to contract. That means getting real relief on austerity is important. But Varoufakis gave up on that fight at the outset by agreeing to continued primary surpluses. The new government was willing to accept austerity lite in place of austerity and call that a victory.

The only alternative to accepting the concept of surpluses, would have been to repudiate the negotiations in January and default. Only they never had any political support for that. In fact they campaigned during the entire elections on the promise that there would be no Grexit. They never would have won had they told voters – “if the Troika reject our demands, we will default!” They were always stuck with what the public would support.

To this day, the Greek people want two incompatible things – 1. to remain within the Euro, and 2. an end to austerity.

Telling them that it’s impossible to reconcile those things will accomplish nothing, but accelerate the rise of Nazi rejectionist parties that tell them that racism and nationalism is the answer.

The tragedy of Greece is not even the most important thing any more. Their dire fate has been sealed once nobody in the rest of the world was willing to stand up and support them, not the European Left, not the U.S. and not Russia or China. The bankers are going to make an example of them and revoke the ELA while shifting the blame to the “lazy” Greek people. The real question is what happens then to the rest of Europe.

Because it’s easy to blame Greece, but not so easy when it’s Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal, then France.

Yves, I think both you and Mr. Chwieroth are highly deluded in thinking there is a choice between continuing to make payment on debts that can NEVER be paid off and defaulting. The reality is that they are going to default (consider that in order to pay off the last tranche of their IMF loan they borrowed from the IMF emergency fund to make the payment!!!). Everything that is going on right now is just theatre. They have almost stripped the population of all money that exists. The Greek economy is still in free fall. The only thing left is to steal money from pensioners. But yet you two seem to think that this is somehow a “solution” for paying off their debt!?!

The other rather obvious thing is that as the can has been continuously kicked down the road, all of the main characters are maxed out in terms of funds that can be made available so the only choice is to print more money and make it available as a loan to Greece to pay off the interest and part of the principle on the existing loan but only if they can find some other means to extract blood from the dead corpse which is the greek economy! Now there’s a solution if ever there was one; Take from the poor to give to the rich!?! One has to seriously wonder if brain cells have atrophied due to living through seven plus years of this insanity. They are going to default and what will happen is the rates will go up in the PIIGS and Draghi will say he will do whatever it takes to bring rates down. But with the ECB on the hook €125 billion in greek (non-performing) liabilities, whose going to believe him?

And yes, Portugal, Spain and Italy will soon be heading in the same direction because although many have been deluded to equate that most undemocratic institution, the EU with democracy and economic well being, the reality is exactly the reverse. Except for the freedom of movement between countries, the EU functions as a fascist entity that serves large corporations and EU politicians by making rules in secret committees that are then dropped on the population like little bombs disrupting economies and adding more and more costs on to businesses. And despite people having less and less real control over their lives due to the EU, they blindly support it despite the increasing levels of pain it brings on EU citizens. Maybe if TTIP is passed and they start to see the impact in their countries, they will start to realise to what extent they are being hoodwinked.

It’s only when those in Syriza start to think outside of the box as to how to really save their country (i.e. dropping the euro, leaving the EU and joining EEA, living within its means, freeing up the economy, cleaning up the corruption, cutting economic deals with Russia, China, etc) and clarify how to communicate it to the populace will they start on the road to recovery.

The example of Venezuela was one where the government was not to blame, yet the voters still turfed out the officeholders who were in charge when it happened. While that is admittedly the only directly relevant precedent, it does seem germane. If Greece were to default, the dislocation in an already distressed economy would be considerable. Voters threw out the old ruling coalition because they failed to get a better deal from the Troika and the economy had taken a big hit. If Greece defaults, Syriza will have failed to get a better deal from the Troika and the economy will take a big hit. And Syriza campaigned on the promise of getting a better deal but will instead have stripped government coffers in making payments during the negotiations, only to eventually default.

The Left Platform of Syriza could see at the end of February that Tsipras’ plan had failed. The party leadership didn’t adapt. This was from a March 12 article with Syriza MP Costas Lapavitsasin Jacobin, It was almost certainly recorded a week or so before that:

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/03/lapavitsas-varoufakis-grexit-syriza/

This has been our view as well. Yet we get hectored as if we are right winger when the hard left wing of Syriza is of the same view as to the odds of the success of Tsipras’ original plan, and that he as the leader of Greece, needed to chart a new course rather than double down on a failed strategy.

I must also point out that after taking a big jump after the elections, the popularity of Syriza in polls as of a couple of weeks ago was back to where it was as of the elections. The odds are good that they have continued to decay as the deposit run has intensified and the government looks increasingly desperate. There is no way a default would increase Syriza’s popularity. The open question is how much of a hit it takes.

BTW, rolling maturing debt is not “printing more money”. And we said in the early stages of the negotiations that the creditors were prepared to reduce primary surplus targets (as they have, it was widely acknowledged that the old targets were ridiculous) and effectively lower the debt due by reducing interest rates and extending maturities. What is often lost in this debate is that Greece’s debt to GDP ratio, in economic terms, is way lower than the face amount. The Telegraph has said 70%, I forget on whose estimate, and Paul Kazararian, who was in my class at Goldman, insists even lower due to all the extensions of principal and lowerings of interest rates.

But even if you buy that, it is well nigh impossible to service even 70% of GDP in debt if 1. you are in a depression and your economy is continuing to contract thanks to austerity and 2. you are locked out of financial markets and can’t roll your debt. The real issue is the structural reforms, not the debt. That was on track to be restructured in real terms until the talks went off the rails.

As to the implications of default on Greece, of course voters are going to blame the government. Not for failing in negotiations, but for failing to deliver results they promised. The question of “how much” will depend on who gets the blame, the Troika or the government.

The entire strategy for Syriza has been to do what it could. It had to negotiate with irresponsible and cruel people who had more power than it did. But, by being the reasonable party in good faith negotiations, they have won domestic political support. They will gradually lose that support if Greece is forced out and the ECB revokes the ELA, leading to a total economic collapse of the Greek banking system.

The main opposition parties, however, are not well poised to gain anything from the collapse of Syriza support. What can they tell the people? “See! We told you it wouldn’t work!” Ok, then what was your program? More Austerity! PASOK and its successors are not going to gain support for a new Austerity program from Greek economic collapse.

The only thing that can happen if voters turn against the left will be a rise of Nazism. So, the political battle will be between the left rejectionist wing of Syriza and Golden Dawn. Varoufakis concluded a long time ago that the European left is not in position to benefit from economic collapse – no more than the Communist Party was in 1930’s Germany.

The only hope for Europe is that the leftist parties can articulate enough of a program to be given the chance to change Europe. The alternative is a return to the dark days of the 1930s.

Syriza’s strategy of reasoning with the Troika failed but they have not abandoned their goals. Since February they altered their approach to one of (what I call) agreeable noncompliance. They have NOT put forth a plan that is acceptable. And it is not in their interest to do so. ‘Proving’ that they can pay the debt would make restructuring unnecessary (resulting in minor adjustments) – what I have called ‘the Catch-22’.

But Greece has turned the tables. Money to pay the Troika will come from the Troika. Or not. The farce is complete. By withholding bailout funds, the Troika forces a default on obligations to the Troika.

=

=

=

H O P

Yet we get hectored as if we are right winger … The real issue is the structural reforms, not the debt.

I think your focus on the structural reforms is probably why you are hectored. You make the case that Syriza is boxed in by their political promises and Troika obligations, which means that this is just a commercial negotiation. If so, Syriza is needlessly weakening Greece.

We saw in February that the Troika offered only minor concessions that would simply ‘punch the ticket’ for Greece’s new government (welcome to the club!). They thought that they were holding all the cards. But Syriza did not accept that (to their credit). They want/demand much more. Thus, Greece has NOT presented a plan for paying the debt because to do so would mean that the promised debt restructuring is nil or very minor. They refused to fall into that trap (a Catch-22).

So it is not just structural reforms. It is debt restructuring. What Syriza wanted from the beginning. Syriza called for ending the farce and that appears to still be their goal.

Now that we are in the end game, Syriza’s agreeableness is fading, and we are seeing more political moves (like Tsipras’s Op-Ed). In the same vein, it seems likely that Greeks will rally behind their government as they near default. Syriza will say that they stood up for the people of Greece. How can anyone argue with that?

What is often lost in this debate is that Greece’s debt to GDP ratio, in economic terms, is way lower than the face amount.

The economic value of Greece’s debt is low only because the interest rate on the debt is much lower than the market would demand given the risk of default. From Economonitor (March 2015):

Further deferred interest, and lengthened maturities is not likely to make the debt more sustainable, just make it bearable enough to extract maximum economic value from Greece. The lowered ‘economic value’ of the debt doesn’t benefit Greece nearly as much as a naive reading would suggest. Essentially, it’s just an indication of what a market price would be.

Question: if Greece defaults, how will this affect the willingness of the IMF to break its own rules and continue pouring money into Ukraine?

Is this one reason why the State Department is pushing so hard for a Greek deal to be done?

Actually should be “for the IMF to continue to break its own rules…”

It takes a political scientist to claim a better understanding of the voters in Spain, Portugal, and Ireland than that of the discredited politicians who are terrified of those voters. For Tzipras, a marxist, the highest priority is not to postpone a eurocratic decree forcing Greece to default– it is to emphasize, at every opportunity, Greek solidarity with Podemos and every such popular/populist initiative.

Podemos’ poll ratings were failing until it moved its messaging to the center in April. One of the hard line party leaders quit over that very issue. And Syriza also had to take a more pro-Eurozone stance to get elected. Podemos has been pointedly avoiding talking about Syriza, Solidarity among the left in Europe has been sorely lacking while Syriza has been twisting in the wind.

This entire article is based on nonsense. Here’s the key: “Governments in Ireland, Portugal, and Spain have adopted a conspicuously hard line stance in negotiations with the new Greek government, partly out of concern that a Greek default would strengthen anti-austerity parties at home (Wyplosz 2015).1 How do we know if a default would have such an effect?”

No. Governments in Ireland, Portugal and Spain are deeply committed to cramming Austerity down the throats of their unwilling populace. They are not afraid that a Greek default would strengthen their political opponents, they are afraid that any leniency towards Greece would highlight for their own peoples that betrayal to the Troika is not “non negotiable” but a choice.

What strengthens “anti-Austerity parties at home” is the failure of Austerity to produce anything but endless failure. Greek default would presumably be the signal for the EU to destroy the Greek banking system and trigger a total collapse of the Greek economy.

That collapse would provide a political argument against parties rejecting Austerity that those pro-Austerity governments will use. “See what happened to the Greeks when they tried to negotiate an end to Austerity with the Troika!”

But, the question these studies forget is “what is the alternative?” You cannot expect people to simply lie down and starve quietly, no matter how convenient it is for bankers and the corrupt oligarchs running these countries for them to do so.

If you want to “study” the situation, simply look at what the political response was across Europe to the Great Depression of the 1930s – the rise of extremist, racist parties, including Franco, Mussolini and Hitler. The same exact thing will happen again. If Socialist alternatives to Austerity are crushed in Greece and elsewhere the consequences will not be a series of Heinrich Bruning Center Parties, which can conveniently ignore the suffering of the people and rule by executive decree of the Troika. It will herald a new wave of Fascism and Nazism, and not just in Southern Europe. The rise to power of Golden Dawn in Greece will be just the first step.

I don’t see how your second paragraph contradicts the quote in the first paragraph that got you so agitated. You also forget that some countries have completed the programs at very high cost, so the beatings are no longer continuing and they regard themselves as star austerity students.

Taking anti-austerity policies to their conclusion in an unsympathetic Eurozone (default for creditor countries that have not exited the program, recall that three countries actually have) and having them lead to even worse economic outcomes in an already deeply depressed economy isn’t likely to look like a very positive outcome to voters in other countries. You forget that Syriza got into office only by appealing to and getting votes from old Pasok voters. Syriza’s success had more to do with the desire to try something, anything different. These voters are fair weather friends to Syriza.

Greece can probably feed itself, or at least one of our readers who spends a lot to time there thinks so. And how can a starving, broke populace rebel against the IMF, the ECB, the EC, and the Eurogroup? They could do a Grexit, but most polls show the public remains opposed, since they know it would make matters much worse in the near term.

This paper completely lost me. What does any of this have to do with the entire system, politics, really anything relevant to the EU mining Greece (soon to be Italy, Spain, etc.) for capital? These survival models utilize export market, incumbent government and the party for which the debt is obligated from what I can see. Even if a correlation is found what of it? Ultimately, how does this help a political problem in a system that is corrupt. If we are assuming the system is corrupt and undemocratic why are we using models loaded with assumptions of sound democratic process? Lots of questions I know but we are entering revolutionary politics territory here.

When Detroit defaulted, did anyone track what happened to the politicos? Did their self-preservation enter into how it played out?

Not sure why Greece should be treated any differently than Detroit, given that Greece is essentially a state and no longer sovereign currency-wise. [At least Detroit gets fiscal transfers, though I thought they should have pulled a Detrexit, lol]

Oh if only they had sold the metro area to Ontario. That’d be worth moving to the hood to get in on.

Another attempt at modeling ultra-complex sociopolitical issues with all sorts of variables into “quantitative results”, in this case using “Partisan spells indicator to measure when incumbent political parties lost office, allowing us to compare results across different democratic systems” and extract “meaningful implications”. Pretty easy to do when the only cause you allow for incumbent political parties to lose office is “all instances of a failure of a government to fulfil ex ante obligations to external private creditors in the first year of default”.

Of course. What other reason could there be? War? Civil strife? Political strife? Social issues? Tiredness at political parties ruling too long? Corruption? Simple incompetence at governing? …. ? … ?

Nah. Of course not.

I can tell historians, sociologists and political scientists are already trembling at the inevitability of losing their tenures to robots with huge modeling calculating powers.

This is what happens when the humanities suffer in a society.

I don’t agree with the interpretation of this article since it assumes that the other countries of Europe will have a choice in defaulting in the wake of a Greek default. I submit that a Greek default will force default onto some of the weaker members of the periphery nations. They won’t have the luxury of deciding in favor of more austerity over defaulting. Like Lehman Bros., the speed of the collapse will be faster than the ability of the political establishment to address. I also believe that because of the shoddy treatment the Greeks have received, they will seek to maximize the effect of their default so that the costs to the Eurozone are catastrophic. They have no reason or incentive to blunt the effect of default since a mitigated default enables “creditor” nations to continue make-believing in the efficacy of austerity and sustains their leverage over a defaulted Greece. Greece has to ensure that default is as apocalyptic as possible so that the other European players’ leverage over Greece is as weakened as much as is possible in the aftermath. Thereby making a Greek comeback more likely

There will be default. There’s little doubt about it since the only concern of the EU leaders is to strangle the Greek Government. There is also little doubt that the whole anti-austerian camp (growing by the day) will sympathize with Greece in all Europe. The consequences are in any case Europe-wide and mid-term.