There’s nothing that beats looking at data to confound conventional narratives.

One of the things that we’ve found to be difficult to combat in covering the Greek crisis is the tendency of the media and pundits to force fit event into convenient black/white narratives. It’s a large-scale manifestation of a cognitive bias called halo effect, in which people (or in this case, governments and institutions) are seen as all good or all bad.

Dan Davies, in a must-read post at Medium, 2010 and all that — Relitigating the Greek bailout, takes on an important element of conventional wisdom, namely, that the Greek bailout was a money-laundering operation to French and German banks. We’ve cited data in the comments section that runs counter to that narrative, namely, that French banks held €93 billion in Greek government bonds at the time of the rescue, Greek banks held €59 billion, and German banks, €40 billion. That factoid alone strongly indicates that the Greek banks would have been toast if the earlier bailouts had not taken place, which would have hurt depositors and imposed massive costs on the Greek economy.

Now that is not to say that the Greek banks were the intended beneficiaries of the rescues. The rolling sovereign crisis was seen as a potential systemic crisis. If any periphery country went down, it posed a threat to the ability of all similarly-situated countries to be able to fund themselves. So the bailouts were to address both the government debt crisis and its tight linkage to banks, particularly the systemically important ones like SocGen, Paribas, and Deutsche Bank. And it is completely fair to say that Greek citizens bore disproportionate costs of this salvage operation.

Another frustrating element of the “French and German banks were bailed out” (and by implication not Greek banks or Greek depositors) is that argument is used for having taxpayers of Germany, France, and all sorts of bystanders (Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland) bear the costs. French and German banks do not equal French and German taxpayers, for the most part. The bank executives, their stockholders, and their bondholders (to the extent that they have meaningful bond financing) got away a long time ago. But with the ire about French and German (and frankly, all the systemically important banks that also benefitted, like US banks), we have yet to hear any of these commentators demand their long-overdue restitution, like cutting them down to size so they can’t go out and be at risk of blowing themselves up again, or better yet, turning them into utilities.

I strongly urge you to read the Davies post in full. You’ll see his figures are different than the onse I cited, which came from news stories at the time of the rescues. Davies goes to some pain that his effort at greater precision is still not all that precise due to differences in data sources, as well as the issue of how to treat Greek banks that were owned by French banks. Bear in mind that the French banks had the options of letting these non-core operations fail; their losses would have been limited to the equity in those subsidiaries.

Here is the key section:

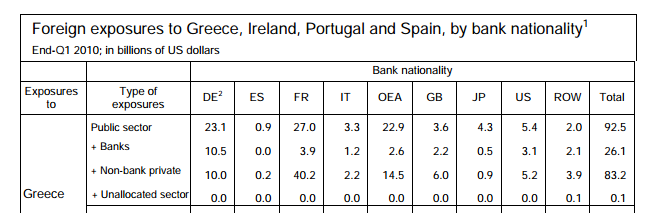

It is terribly easy to get confused about patterns of exposure to Greece from European banks, because the statistics at the time were reported every which way, and the fact that three of the biggest banks in Greece were owned by foreign entities meant that the consolidated numbers were often heavily distorted….You can see that the headings on this contemporary table put together by the BIS have a scattering of footnotes indicating various data issues — however….I think these numbers are broadly correct. For the purposes of this analysis, I will go with about EUR25bn in Germany, and about EUR27bn in France.

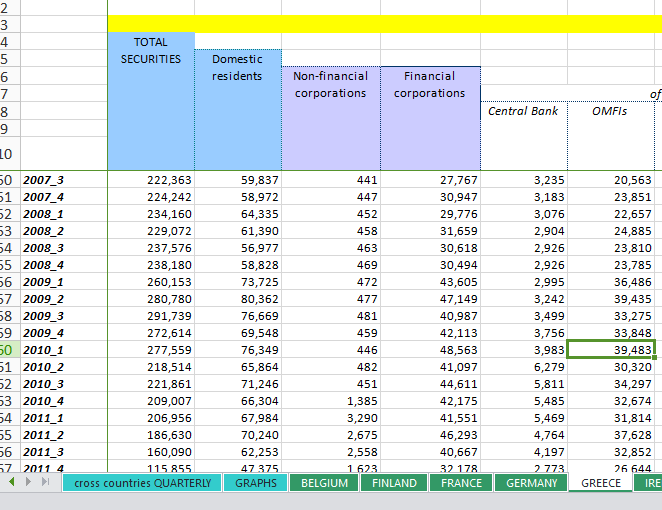

Data for domestic bank holdings is made a lot easier by the heroic work of Sylvia Merler and Jean Pisani-Ferry at Bruegel, who have put together a comprehensive time series for government bond ownership. As of Q1 2010, the Breugel dataset records Greek domestic banks (OMFIs, column G in the spreadsheet) as holding just under EUR40bn of government debt.

It is not clear — and probably impossible to know — to what extent this EUR40bn figure double-counts the government bonds held by Emporiki and Geniki, but for reasons to be discussed below, I don’t think that matters so much.

So we can say the following things, just from the data:

1) The majority of Greek government bonds were held by non-Greek residents — Merler & Pisani-Ferry reckon about 72%.

2) However, the Greek domestic banking system was far and away the largest single holder, almost as much as French and German banks put together

We also know:

3) French banks, in particular, had a lot of their Greek government exposure through subsidiaries, and could at least in principle have reduced their losses in the event of a Greek government default by taking advantage of limited liability.

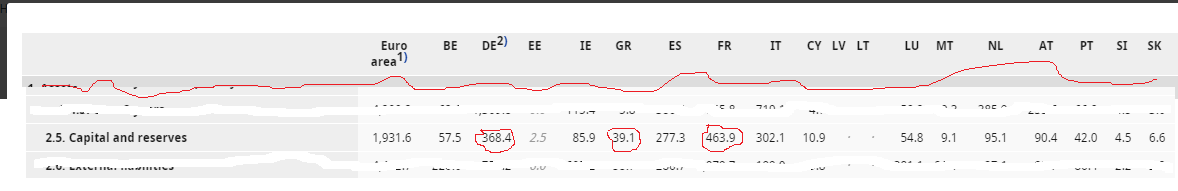

4) When we compared the GGB exposures to total capital and reserves, we can see that the Greek domestic banking system in April 2010 had EUR39.1bn of reserves, while the French system had EUR463.9bn and the German had EUR368.4bn.

Probably better to just check out the dataset at the link rather than suffer this adventure in Microsoft Paint. Figures for Q1 2010.In other words, a write-off of all Greek government debt would have been a deep flesh wound for the German and French banks (around 6-7% of total capital), but a complete wipe-out for the Greek banks (just under 100% of capital and reserves).

Don’t take the calculations in point 4 above too seriously. It’s always a bad idea to divide numbers from different datasets, and it’s also not really possible to aggregate capital across banking sectors this way — if all the capital is in Bank A but all the GGB exposure is in Bank B, then you can’t set one off against another. But the general order-of-magnitude is about right and accords ….The French and German banks would certainly prefer not to have lost the money, but could take it (with the possible exception of Commerzbank, which had very weak capital and large exposures). The Greek banks, on the other hand, would have been bust immediately.

So I think the more incendiary rhetoric — anything claiming that the 2010 bailout was a con-trick that was only organised to prevent a state bailout of the French and German banks — can’t be stood up. Nonetheless, I do think there’s a lot of truth to the view that a strong motivation for the bailout was to preserve financial stability in Europe.

Bear in mind that I think Davies overstates his case a bit. Deutsche Bank was fabulously thinly capitalized. Moreover, we saw in the US how losses (here due to subprime loans and bonds and CDOs) could put an institution with derivatives exposures into a death spiral. Losses lead to credit downgrades. Credit downgrades lead to bigger haircuts on derivatives positions where the bank has to post collateral. Downgrades also lead to higher funding costs. That can lead to more downgrades….And SocGen and Paribas were very big derivatives players.

But it’s important to keep in mind that the really big French and German banks’ viability would have been in serious doubt, and that plus the fact that all sorts of governments couldn’t fund themselves led to a series of panicked, “let’s do what we need to fix the immediate problem” which might not have been terrible if the Eurocrats had gotten religion about addressing the longer term issues. So while Greek banks were rescued from what otherwise would have been certain death, too many of the costs of the entire operation were foisted on Greece. Even worse, the wounds have been allowed to fester and turn into gangrene.