Our mini-fundraiser for Water Cooler is on! 28 donors have already invested to support Water Cooler, which provides both economic and political coverage, at a time when former Clinton Administration official Brad Delong announced, following the purge of two Sanders-supporting writers, that those deemed to be too far to the left will be “gleefully and comprehensively trash[ed]” come November. Independent funding is key to having an independent editorial point of view. Please join us and participate via Lambert’s Water Cooler Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal.

By C.P. Chandrasekhar, Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics and Chairperson at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Originally published at Business Line

Ever since the Global Financial Crisis, advanced economies have been grappling with the spectre of deflation. While this was very clearly a reflection of the downswing in economic activity in the aftermath of the crisis, such price deflation has proved remarkably impervious to the most expansionary monetary policies and liquidity expansion that the world economy has yet seen. This has had adverse consequences in terms of producers’ expectations, which in turn have kept investment low. It has not benefited working people because wages have stayed low or continued to fall. And it has generated tendencies of the debt deflation-type that Irving Fisher had warned against, whereby the real value of debt and of debt servicing keep rising because of falling prices, and make it harder for debtors to deleverage or to increase their spending.

All this has been true of the developed economies at the core of global capitalism for some years now. But in general it was presumed the developing countries, especially the more prominent emerging markets, were less prone to such tendencies. Indeed, because the developing world as a whole continues to grow faster than the North, and because some large emerging economies like China and India continue to experience recorded GDP growth rates of 6 to 7 per cent, it was perceived that they would also have inflation rates that would show rising or stable prices. In countries such as India that are still hugely affected by agricultural cycles affecting food prices and other forms of sectoral supply bottlenecks, there seemed to be no reason for prices to fall, beyond the secondary impact of the global fall in prices of primary commodities like oil.

However, it now appears that this too was a misconception about the new economic patterns emerging in the Global South, including in economies like those of China and India. Recent trends show a remarkable – and worrying – convergence of producer prices in these countries with those in the advanced economies, where price deflation has become rampant.

Deflationary tendencies were already evident in China from about five years ago in terms of producer prices behaviour. This was not a surprise given the huge expansion of production capacity that had marked the previous decade, which had led to both production gluts and significant overcapacity in many producing sectors. This was for some time partially hidden by the construction boom unleashed as part of the recovery-and-stimulus package unleashed by the government. But as that package also led to dramatic increases in debt across all sectors, it too now seems to have run out of steam.

As a result, as Chart 1 shows, producer prices in China have been mostly falling or flat since mid-2011. For the last three years, even consumer prices have decelerated, which is somewhat surprising in an economy that is still supposedly growing at around 6.5 per cent in terms of GDP.

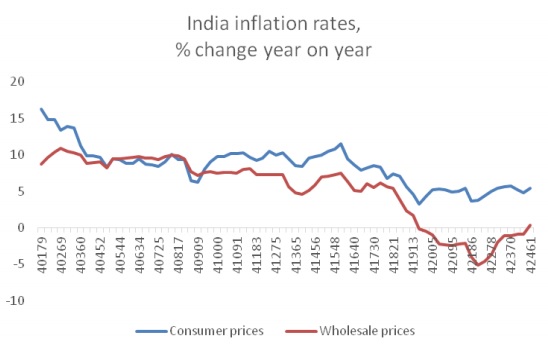

The case of India – described in Chart 2 – is even more surprising. In fact, the Indian economy is not usually described as on currently facing demand deficiency, and supply bottlenecks are more usually mentioned as the major constraints on economic activity. Yet even in India, while retail inflation (or the consumer price index) still remains relatively high (in excess of 5 per cent per annum) it has fallen considerably from the earlier rates of around 8-10 per cent. Much of this is the result of food price inflation, which obviously impacts directly and disproportionately on the bottom half of households.

However, the proxy for producer prices (wholesale prices) show a sharp deceleration even in India. More significantly, wholesale prices in India have actually been falling (on a year-on- 2 year basis) since January 2015, that is for well more than year now. This obviously will have a similar depressing effect on both producer expectations and investment in India.

Chart 1

Source: CMIE database, accessed on 21 May 2016.

Chart 2

Source: CMIE database, accessed on 21 May 2016.

It is worth noting that such price decelerations and even declines have occurred despite other variables moving in ways that are assumed to have inflationary impact. Thus, as Chart 3 shows, nominal effective exchange rates (calculated for a weighted basket of trading partners) have depreciated for both China and India in the recent past, with no appreciable impact upon domestic inflation.

Chart 3

Source: BIS database, www.bis.org., accessed 21 May 2016

Further monetary policy cannot be accused of being too tight in China at least, and China has also seen a dramatic expansion of debt to GDP indicators across all sectors. Even in India, while nominal interest rates are considered high by many, the central bank has been biased in favour of measures that would ensure there is enough liquidity in the economy. It is true that declining oil prices and falling or stagnant prices of other primary commodities have reduced import prices for both countries, but for some time now the prices of oil while remaining low have not fallen further. Obviously other factors must also be at play in the ongoing producer price deflation in both countries. It may be that the features that have operated to cause price deflation in the advanced economies – inadequate effective demand because of suppression of wage incomes and continuing emphasis on fiscal consolidation, with very loose monetary policies no longer working as stimulus – are also operated to at least some degree in these economies.

Clearly, the lack of “decoupling” of these economies from the advanced economies goes beyond GDP and extends also to the behaviour of producer prices. This can only add to the concerns for policy makers in both countries, especially in India where debt default is already putting major strains on bank balance sheets.

In 1988 they held it together until after the election. In 2008 they failed. My guess is that TPTB will size up the nature and size of the crisis looming and either stonewall for all they are worth or time the thing so that they have the maximum amount of panic with the minimum chance for debating any alternative to the “jam cash down the malefactors’ throats until they are made whole” policy. It is unlikely but hardly impossible that they will lose control and the crisis will hit when it will, but my guess is that like 2008 they will see it coming then game it to get the outcome they want.

Well, China and India always wanted to catch up to the West. Be careful what you wish for…

OH NO! the price of things is going down, what a horrible thing! We’ll all have to pay LESS for the stuff we need, how disastrous!

[Squeaky little voice in the back of the room says “um but professor, isn’t that what used to be known as ‘progress?'”]

As my father, who was born in 1922 once told me, you could buy a car for $700 when he was a boy: problem was, no one he knew had $700. Deflation creates the conditions under which everyone hoards their money (why not? with prices dropping, it makes more sense to buy tomorrow than today), demand collapses, and people get thrown out of work. Also, as prices fall wages get cut, especially in places like India and China (here they just close shop and move to a lower wage zone here or abroad). It’s a vicious spiral.

Sure, I will hoard my money as prices fall. As soon as I pay for groceries, pay rent, pay medical bills, pay utility bills, pay for gasoline, pay school tuition, and pay everything else that will not and cannot wait, yes I promise I will hoard whatever’s left.

And we don’t have a “wage” problem, we have a “money” problem: in 1975 the minimum wage was 5 quarters per hour, $1.25, and today the silver value of five quarters is $15.55. When money is no longer a store of value and does not maintain its purchasing power, this is where we end up.

All price decreases are not the same.

I’d put it this way, deflation is an artificial decrease in prices, caused by a decrease in money supply. That’s different from a decrease in price as the result of an increase in supply of some thing or a decrease in demand for that thing.

Deflation means your wages go down, along with all other prices, while your debts, your house payment, car payment, credit card payments, student loan payments, remain the same.

Put differently, your payments remain the same but the cost of dollars, how many hours of labor you must give to get a dollar, keeps going up.

The winners in a deflation are the people who hold dollars or are owed dollars.

Perhaps if the fatuous ‘policy makers’ were fired en masse they would begin to understand this.

. . . It may be that the features that have operated to cause price deflation in the advanced economies – inadequate effective demand because of suppression of wage incomes . . .

When all your money is spent trying to stay alive, what’s left?

We need to automate demand/consumption!

As long as we let the NY Fed run the country we will continue on a path of self destruction.

“The Sun tells its readers that the Brexit vote “is our last chance to remove ourselves from the undemocratic Brussels machine.” (The EU operates out of Brussels.) Americans have yet to have the chance to vote on removing themselves from the undemocratic Federal Reserve where citizens are stripped of the right to elect either the Board of Governors or the boards of the regional Fed banks.”

More……….http://wallstreetonparade.com/2016/06/uks-largest-newspaper-says-run-for-your-life-vote-brexit-americans-should-listen/

It is policy, US policy.

Expansion of liquidity protects the rich, but does not benefit the poor, because the money goes towards propping up the neoliberal shibboleth.

Working people do not benefit because propping up the Gibson shibboleth pays few wages, and thus far not increase demand.

Increasing demand damages China, and by extension raw material suppliers, countries where, due to neoliberal trDe nonsense, absence a local manufacture policy.

Demand is further suppressed.

At this point one has to distinguish between public hand wringng, and behind the scenes policy to suppress demand.

We know how to create demand, good social programs distribute money to the poorer and they spend it on goods and services. Unlike the rich, who “invest” and buy a megayacht or two.

Who gains and who suffers, geopolitically? The US, having sent it’s consumer manufacturing to China, where China promptly to advantage of the gifts of jobs and built a powerhouse economy to challenge the US rule of empire.

This could Not Be Allowed, and the solution, opportunistically or deliberately based on a housing bubble which destroyed the non wealthy’s wealth, was to depress Consumer Demand to humble China and raw material producing countries.

Uppity peasants that they were.

The adventures in the ME and Latin America a appear more focused on destroying regimes who demonstrate streaks of independence from the US, than any other behaviour.

TPP and TTIP, and TISA, and the EU are all a part of removing sovereignty and extending US hegemony. Evans-Prichard’s essay in the Times about Brexit was a reaction to loss of Sovereignty.

He’s spotted part of the plot. When will he see the whole picture?

When will y’all see a pattern in the fabric, instead of a swirling mess?

Nonsense. No matter how much our intellectual class repeats this, that does not make it true.

For starters, the ‘advanced economies’ are not one unit. The US, UK, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, and others, are actually dealing with rather different challenges.

Second, in the biggest ‘advanced economy’ – the US – it is inflation that is running rampant, not deflation. From real estate to stocks, from healthcare to college, from the national debt to the Fed balance sheet, if one is going to make a quantity-based argument, then the only position consistent with reality is that the quantity has gone up, not down, over the past few decades. It’s a condition that is particularly indefensible since productivity has increased a great deal over the past few decades, which means, holding all else equal, prices should not only not be rising, but things should actually be cheaper today.

The answer of course is that this has nothing to do with the spectre of deflation. It’s not about quantities or aggregates. Rather, it is the spectre of inequality, the distribution of resources, which is a very different problem.

P.S. Thought it might be fun to link to a few charts where the lines trend up, not down:

Median Price of a new home (Census data)

All Sectors debt level (Fed data)

GSE size (Fed data)

State and local taxes (Census data)

Federal Debt (Fed data)

Federal Debt relative to total population (Fed data)

Federal Debt as percent of GDP (Fed data)

Health expenditures (Fed data)

Health expenditures per capita (Fed data)

Personal Income per capita (Fed data)

Student Loans (Fed data)

Auto Loans (Fed data)

Federal Reserve total assets (Fed data)

This guy has done a nice job, overall it’s running around 10%:

http://www.chapwoodindex.com/

I would be happy to throw some money in the tip jar, if there were a way to do it that didn’t involve giving PayPal my address, phone number, email, etc. They don’t need those things to process a debit card transaction.

Likewise. Apparently we’re supposed to trust PayPal. I don’t.

If you follow the link, it shows you how to give by check.

So, deflation despite a population growth rate in India of 1.2% p.a.(compared to 0.5% in China and 0.7% in the US). That is despite the fact that human population growth worldwide has resulted in the extinction of 30% of the other species on the planet in the last 40 years according to WWF. Does nobody else agree that we have collectively pushed our economic model to the nth degree, causing what is now toxic growth , which in turn is threatening both our quality of life and the survival of the ecosystems which we depend on for survival?

We’re just doing our job as a species, exploiting our capabilities and our niche to the fullest. Someday we’ll just be an interesting geological layer, Earth and Nature no doubt will persevere.

Yeah, but we humans have big brains with the power of consequential thought. Sadly, most of us only use them for short term, material self interest with little or no consideration for the long term, or other species, or in the case of financial elites, other people. We could do a lot better, but we don’t. As long as we can have a few beers, a good takeaway and a good game on a big screen TV most people don’t give a s*** about the state of the planet.

It is interesting to see how WPI in India is pretty correlated to the collapse in commodity prices. Interesting, but not surprising given the weights assigned to the WPI ( Wikipedia has the weights https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inflation_in_India).

I tried looking up the CMIE data in the graphs, but it appears to be a think tank/ financial services group. I could not find the relevant info, but probably because you have to purchase it. I mention this because the Indian government calculates CPI very differently from what NC readers might expect. Historically they had several CPI values which correspond to different population segments. The headline, as I have been told, is a particular segment called the CPI-IW (industrial worker). That matters because it could explain the befuddlement of the authors wrt rate of GDP growth given rate of CPI growth.

China and India have developed in a global economy and are dependent on the Western consumer to absorb much of their production. The Western consumer never recovered from 2008 and Western policy makes things worse, the excess supply of both nations now drives down their own inflation rates.

The low interest rates in the West keep asset price inflation rampant.

Everyone needs to re-learn there are two sides to Capitalism and learn some lessons from Adam Smith.

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Adam Smith saw landlords, usurers (bankers) and Government taxes as equally parasitic, all raising the cost of doing business.

He sees the lazy people at the top living off “unearned” income from their land and capital.

He sees the trickle up of Capitalism:

1) Those with excess capital collect rent and interest.

2) Those with insufficient capital pay rent and interest.

He differentiates between “earned” and “unearned” income.

Throughout the West we have seen a parasitic financial sector look to turn the disposable income of nations into interest payments for itself through housing bubbles.

Money that was once spent on goods and services is now sucked up by the financial sector, it’s bad for business.

The high house prices mean high mortgage payments and rent, raising the basic cost of living. The basic cost of living sets the minimum basic wage pricing nations out of the global economy, it’s bad for business.

Capitalism has two sides, a productive where “earned” income is generated and an unproductive side where “unearned” income is generated.

You tax the unproductive side to fund the productive side, providing things like low cost housing to keep the cost of living and minimum wage down.

Today we do the opposite and look at income tax on “earned” income as the main tax base raising the cost of labour.

Michael Hudson’s “Killing the Host” goes into more details and he knows from experience.

He worked on Wall Street and helped look into South American economies to work out how much surplus was available to turn into interest payment for banks.

The banks have used housing bubbles to turn the household surplus into interest payments to themselves rather than purchasing goods and services and stoking demand, it’s bad for business.

Western ideas are destroying their own economies and these ideas stop them seeing what is going wrong.

Adam Smith also tells us what successful productive companies look like in a capitalist economy.

“But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the declension of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

Sufficient wages are required to provide demand for goods and services.

Investment is required for the company to grow and provide more and more jobs.

The investor reaps his rewards through the ever rising share price.

Amazon shows how big a company can grow when it isn’t paying out dividends and constantly reinvests.

It is exactly the opposite of today’s thinking.

When rates of profit are very high, capitalism is cannibalising itself by:

1) Not engaging in long term investment for the future

2) Paying insufficient wages to maintain demand for its products and services.

The activist share-holder is the most pernicious, parasite that rides on businesses looking for “unearned” income.

How can I turn someone else’s hard work into income for myself through dividends and short term share price inflation?

He looks for things that can be sold off, large capital buffers and pension funds that are in surplus to be turned into dividends.

Short term share price inflation for capital gains is achieved through share buybacks funded through debt.

The businesses of the real economy are something for the parasitic investor to feed off and bleed dry.

Adam Smith may have solved today’s problems.

Concentrating on profit and dividends kills reinvestment for growth.

There is insufficient demand through high living costs and low wages.

They were very smart in the 18th Century.

You must train the financial parasite into two productive modes of operation:

1) Feeding abroad and bringing the profits home.

2) Lending into productive businesses in the real economy for investment, not for share buybacks or mergers and acquisitions.

The well trained parasite can be effective, all the Asian tigers in their most productive phase, limited bank money creation to lending into industry and not their usual speculation.

After decades of success in Japan, the banks were allowed to lend into real estate, they killed it all in no time.

Monetary policy relies on some material basis, if not gold, then oil or other metals and commodities. The financial market can’t be completely divorced from the real market.

China has gold in the government basement. India has gold in the temple basement. One is publicly held, the other one is privately held. That is why India, not China … is desperate to separate the Indian people from their gold, same as FDR … but China being a one party dictatorship, doesn’t have this problem. The mandarins in Beijing control all. China uses many metals as their reserve, not just gold. India is poor in that respect.

Deflation means that demand is falling, or the money supply/velocity isn’t keeping up, or both. Both countries are ignoring my point earlier concerning global currencies … given the size and rate of growth of these societies, no metallic basis is enough to prevent deflation, and neither have much domestic oil either. Coal in China is much less fungible for international trade than oil or gas … and China was a net importer of Australian coal.

Inflation is caused by over creation of money and is an evil to be avoided. Even 2% is too much.

The FIRE sector is really related to Piracy without the terror ….. except when the system resets!

Clearly, the emerging economies need more Banksters!

I hear the Rothschilds have been in Hong Kong a long time, and are involved in the move of the metal repositories from London/NY to Hong Kong/Shanghai.