Yves here. One of the many ironies of the bezzle called Ethereum is that its promoter act as if it is something terribly novel. In fact, the problem of how to pay someone for goods who is in a completely different legal jurisdiction that you don’t know and therefore aren’t sure you can trust has been settled a long time ago because international commerce depends on it.

It’s called documentary letter of credit. You want to buy something from China, say a certain number of iron beams of a specific shape and length. You don’t know if you can trust the seller to provide what you want. He might ship 15 instead of 20 beams, or send beams that are off your spec. The seller does not want to ship anything across the ocean unless he is sure you have the money and won’t just walk off with his goods at the port of disembarkation without paying him.

The solution is a documentary letter of credit. The seller and buyer go to a bank. The bank guarantees payment provided the seller presents documents that attest that the shipment is what it says it is. There are typically quite a few documents (which party provides what document and what the document has to say is set forth in detail). The shipment will not be released to the buyer (as in title will not be transferred) and the seller will not be paid unless the documents match the LOC requirements exactly.

International LOCs are a mature, low margin business. I did an international trade study for Citibank in the early 1980s (it was looking for a way to “innovate” this very well settled, dull but paperwork intensive business way back then). It would have been normal for McKinsey to say, “No, there is a good reason there is no magic answer here.” We came up with a clever idea the client adored (it required entering into a different sort of relationship with some key transport companies). But the manager on our team was recovering from a nearly fatal ailment and was only scheduled to work on this project a month. The rest of us didn’t want to continue with an unknown team. So a second team came in, engage in a massive case of “not invented here” and proceeded to tear down our proposal. The immediate client team at Citi was furious because they regarded our work as more credible, but there was no way the higher-ups would go further if Mighty McKinsey had given a thumbs down.

By Clive, a bank IT professional and Japanophile

The ability to return interest rate policy to something vaguely approaching historic norms continues to elude central banks. Like the unfortunate perpetrator in an episode of Columbo, the economies subject to their ministrations keep showing up at inopportune moments and even if the central banks can talk their ways out of the last uncomfortable fact-set, there’s a succession of “just one more thing’s” one of which always gets them in the end.

Perhaps if they hadn’t colluded with governments in administering a double dose of high levels of household debts and falling real incomes, they’d be less culpable. But since the central banks were co-conspirators, it’s difficult to let them escape responsibility for their actions or lessen up on our insistence they confess that monetary policy alone cannot resurrect economies which have been suffocated through lack of demand.

And that’s before we’ve even started on the possibility that a 200-year growth cycle based on the apparently infinite availability of natural resources might not, after all, be limitless.

There’s plenty of incriminating evidence that zero, or close to zero, interest rate policies are enabling new speculative bubbles. Insipid consumer demand prevents a more generalised bubble in stock market valuations but so-called new economy start-ups are deemed innocent until proven guilty in terms of being susceptible to underlying economic fundamentals.

There is some much-needed scepticism. Microsoft’s purchase of LinkedIn for $26.2bn has been widely ridiculed. Justifiably so given the amount paid for a collection of validated email addresses and comically inflated career histories.

But Amazon moving into grocery delivery is another example of big corporations either sitting on cash piles they can’t sensible spend or else have access to funding at almost zero cost ploughing the money into implausible projects. In a sign that hope is still triumphant over history, Amazon’s investment hasn’t been seriously criticised. Grocery delivery is top heavy in terms of operational gearing (you burn through money maintaining infrastructure even if you don’t sell a single thing) and in mature markets there’s already saturation coverage. Amazon’s supply chain and logistical know-how are no better than anyone else’s – or, being generous, if it is, the difference is marginal – and it lacks any particular technological innovation compared to the established competition. It’s just hoping it has deeper pockets than anyone else. But throwing money into a hole and setting it alight isn’t a serious attempt at a strategy, it’s more like a cry for help.

At least these new-economy fantasies have some conventional, almost plausible, business models. Some others though are so far removed from any discernible legitimate method of generating earnings, never mind profits, they are proof positive that we’ve entered the economic Twilight Zone.

One such start-up is called Ethereum. Put simply, Ethereum is a trading platform supposedly (it isn’t, but this is what we’re supposed to believe) without a nation state, a legal system, or recourse to law enforcement.

Where two or more parties wish to conduct a business transaction, the agreement between the parties is transcribed into computer code. The code is the “law”. Settlement on performance of the contract is done in a virtual (crypto). Transactions on Ethereum (and similar platforms) are colloquially referred to as “Smart Contracts”. For a more comprehensive description of Blockchains, Cryptocurrencies and Smart Contracts, is an excellent overview. Written for an IT and legal audience, it does discuss the implications for both the law and technology in the vocabulary of the respective specialisms, but you can skip these sections without losing any of the main points.

While Naked Capitalism readers may well be scratching their heads and even rather cynical, all of this kind of thing is catnip to the global mega corporations, with IBM, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, Nasdaq, and the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission rumoured to be interested. What is there not to like?

I could start by mentioning that stateless contracts, if they could ever exist, which they can’t, are by their very nature free from regulatory oversight and tax liabilities. But to the sorts of companies listed above, these are benefits not drawbacks so I won’t waste my breath making appeals to notions of a responsibility to society. And the mind-set of today’s transnational corporate elites is that it is the corporation which bestrides the state and not the other way round so ditto any pinko tree-hugging nonsense about undermining the institutions of government such as the rule of law and law enforcement.

Taken at face value, a Smart Contract has no risks arising from non-payment for performance. This is because the benefit paid as a result of performance to contract is made “up front” and held in the Ethereum platform’s escrow feature. Validation of performance is triggered by an agreed external input, supposedly neutral and not susceptible to tampering or influence. So whatever is described in the Smart Contract terms is either delivered or it isn’t and if it is delivered payment is automatically released to the beneficiary. Fine, but just so long as you’re willing to buy into the assumption that the Smart Contract exists only in the Ethereum vacuum.

Let’s rewind a little and consider why it is that we’ve been “limited” to “dumb” contracts, performed (or not performed, as the case may be) within the jurisdiction of a nation state, subject to laws ruled on in courts and enforced by the recourse to state intervention. Was this simply due to a constraint arising from the lack of technological innovation, a constraint which it is now possible to free ourselves from?

This seems unlikely. Stripping out the “smart” aspects of a Smart Contract, it is still a contract, albeit wrapped in a new-and-improved packaging of object-orientated programming and cheap, distributed computing power. Contracts are not new. And neither are their limitations. I’ll cover two here in the remainder of his article. There are many others, but hopefully readers will then understand why even with only these two pitfalls, it is not just desirable but an absolute necessity for a nation state to exist and for any contraction be encompassed within the jurisdiction of one. And furthermore, for whatever jurisdiction the contract is subject to, why that jurisdiction should offer as close to legal certainty as it is possible to have through its legal system and a fair and measured sanction of state-monopoly violence available as a penalty for non-performance.

Unjust Enrichment

One of the risks associated with doing business by means of contracts, be they traditional or smart ones, is how to resolve situations where the parties to a contract are bound to perform whatever is stipulated in the contract, but due to circumstances which weren’t envisaged when the parties agreed to abide by the contract, continuing performance of the contract results in perverse and unreasonable outcomes for one of the parties.

By their very nature, such situations are complex. Ordinarily, you shouldn’t be able to walk away from performing your part in a contract. That’s the whole point of a contract – it is like private law, you’re supposed to abide by it. If one or both of the parties didn’t want to be beholden to the contract they should not have agreed to it and there should be penalties for non-performance.

But these situations can and do arise. One of the two reasons covered in this article is that a contract has fallen because one of the parties who agreed to it was not permitted to enter into the contract. This was exactly what happened when the Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York (part of JP Morgan Chase) sold and interest rate swap to a county (Lothian Regional Council) in Scotland. It is worth noting that interest rate swaps are precisely the sort of contract which smart contract promoters foresee as being the most suitable for running statelessly as a Smart Contract. We’ll debunk the whole notion that you can pretend-away the state when you enter into a contract.

Unfortunately for Lothian county it turned out that UK counties were prohibited by statute from entering into this kind of interest rate swap deal. The contract contained the usual clauses for this type of interest rate swap covering early termination and the calculation of penalty fees. But these were useless for both the county and Morgan Guaranty because it wasn’t that the contract had been terminated early by Lothian; it was that the contract could have never legally existed in the first place.

So what happened when the music stopped and the UK Supreme Court (then known as The Law Lords) ruled that all interest rate swap contracts between counties and banks were voided?

Well, sometimes the banks were in the money and the counties had to eat losses and sometimes it was the other way round. In the case of Morgan Guaranty and Lothian county it was the county which had, for once, benefitted from the swap. Morgan Guaranty had continued to pay out on the contract right up until it had been voided and sought to recover its losses. But Lothian country had some of Morgan Guaranty’s money and wasn’t about to give it back. The county argued that it was entitled to sit on its gains right up until the point where the contracts were ruled as fallen.

You have to admire Lothian’s pluckiness. It refused to pay Morgan Guaranty a penny. As it had the money and Morgan Guaranty didn’t, the contract was voided and Morgan Guaranty couldn’t use any early termination clause and Lothian didn’t care in the least if it annoyed Morgan Guaranty, there didn’t seem much that Morgan Guaranty could do about it. How was Morgan Guaranty to respond?

Of course, Morgan Guaranty – bastion of free enterprise, master of cutthroat capitalism at its finest, first to tell anyone that a deal is a deal is a deal – went running to the state (the Scottish legal system in this instance) for help. It cited the principle of unjust enrichment.

To cut a long story short, Morgan Guaranty won. The case was not at all straightforward – the case was held before five judged instead of the usual three on account of both the byzantine points of law and the implications for what precedents their ruling would set. Unjust enrichment is always fact-specific and mired in legal complexity because if it is successfully proven the judgement ends up interfering in something that was never intended to be touched (the contract).

The legalese in judgement gives a hint to how gruesome the legal arguments are in a case of unjust enrichment and how important well-settled law is when a contract ends up going wrong. The jurisdiction which Morgan Guaranty and Lothian county’s contract was subject to (Scotland) was able to rely on case law dating back to 1696. To put that in context, this was nearly a century before America became a post-colonial independent nation and even started to develop its own laws. To make a definitive ruling in Morgan Guaranty vs. Lothian, the Scottish equivalent of the Supreme Court even had to go back to Roman contract law to establish basic principles of equity.

What we can learn from this in relation to Smart Contracts is that it took one the best and most accomplished and definitely amongst the more trustworthy legal systems in the world over three hundred years to provide legal certainty in relation to an important contractual principle. Smart Contract platforms such as Ethereum throw all that away. Worse, it’s not even discarded by accident, inadvertently. The proponents of Smart Contracts, unbelievably, actually see this as an advantage.

In an irony which one must assume is totally lost on the likes of Barclays and Goldman Sachs in their rush to investigate Ethereum and its ilk, it was recourse to a state, a legal system and the rule of law underpinned by effective enforcement that JP Morgan Chase so benefitted from in its tussle with Lothian county. Had Morgan Guaranty and Lothian written the same swap deal on the Ethereum platform, Morgan Guaranty would have had to – presumably – post increasing amounts of collateral into escrow as its position on the swap deteriorated. The fact that Lothian country officials were never permitted to enter into such a contract would not have mattered at all to the Ethereum algorithm.

Of course, had the roles been reversed and it was Lothian county which was sitting on the wrong side of the contract in terms of benefiting or losing money, it would have been prohibited from posting further collateral to support its loss-making position. But in the absence of a state to enforce the performance of the contract, what, exactly, would Morgan Guaranty have been able to do about it?

To further emphasise the point, Ethereum is barely out of diapers but has already found itself in a predicament caused by potential unjust enrichment. Bloomberg’s Matt Levine has ably covered the story in detail, but in essence, a legitimate feature of the Ethereum platform was exploited for financial gain in a way which complied with the letter of the platforms rules but hardly the spirit. No doubt that within the body of Ethereum users and rule makers, moves are afoot to decide and implement governing principles to cover what happened and start to figure out what the rights and wrongs of the various actors, technologies and enforcements involved are.

Don’t worry guys, you’ve only got another 300 years on the learning curve to go.

Unfair Terms (English Law) \ Unconscionability (U.S. Law)

It is sometimes helpful to think of contracts in terms of being “private law”. Within a nation state, individuals or groups can become a party to a contract. The contract is enforceable on the parties to it but the state can be invoked by a party to the contract to impose remedies for non-performance.

This has long sat uneasily for the society which forms the population of the state. One the one hand, the individual citizens of the state want to have the freedom to enter into private contracts. But then enforcement of a contract, potentially though violence, is too onerous a consequence to be left to the individuals to mete out or withhold according to their own judgements. So the individual citizens grant the state a monopoly on violence but the state doesn’t respond to individual notions of how that monopoly should be used. Rather, societies create the boundaries.

One boundary which has emerged through the pressure of society on the state is that, where a contract is drawn up between the parties to that contract, should the contract contain conditions which are so manifestly egregious or where the balance of power between the parties to the contract is so unequal as to render enforcement of the contract unjust, the party seeking redress for any non-performance of the contract cannot expect any intervention from the state or, perhaps more importantly, the state’s agencies of enforcement.

In many jurisdictions (I will concern us with only English and U.S. law here for the sake of simplicity but this concept is present in other nation states too) there are regulations which exclude or limit contractual terms or such limits are implied by common law. These are usually in play if clauses restrict liability, particularly negligence, of one party. The clause must pass a “reasonableness test”.

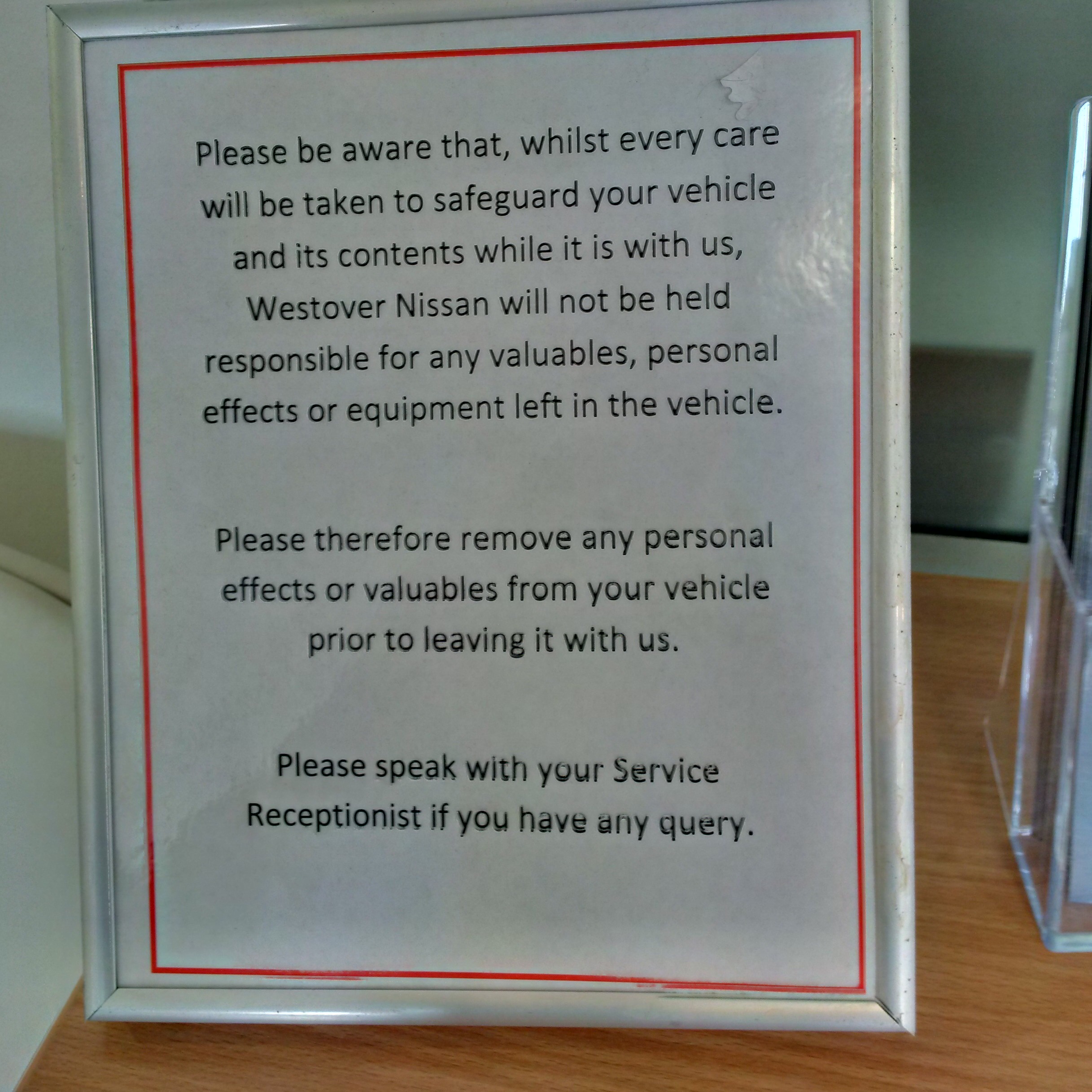

Another thing to add to the list of Things You See in Everyday Life that are More Important that you’d Think, this is a typical example of a term in a contract which is potentially “unfair” (in the English jurisdiction) or “unconscionable) (in the U.S.):

The notice was in the service area of a car dealership, which I visited with a friend while their car was in for a scheduled maintenance check. The “service due” message had appeared so the vehicle was booked in and the usual routine overhaul was performed.

Futurising but not too much, this is the kind of transaction which could be moved to a Smart Contract. The vehicle in question was fairly new so it had alerted the dealership and the owner to arrange a trip back to the mechanic. There was a standard checklist specified in the service schedule (oil change, brake pads, emissions control test, tyre inspection/replacement) and the vehicles on-board diagnostics recorded the completion of these items. It would be a small step to then have the on-board telematics forward this information to a Smart Contract platform such as Ethereum and have RFID tags verify any replacement parts had been fitted.

The dealership would want the customer to be bound by the terms in the notice above. And superficially, there isn’t anything too objectionable about it. What the dealership is telling the customer is if you leave valuables in the vehicle, don’t expect us to be responsible for them. If anything happens, we will not assume liability for your losses.

So that’s that, then? No. Despite what the notice says, the dealership is liable if it fails to act reasonably in respect of your property. If an employee of the dealership steals them – and the dealership has cause to be suspicious of that employee but had not acted on those suspicions – you could make a claim on both the employee for theft in a criminal court and against the dealership for negligence in a civil court. Similarly, if you left a $500 smartphone in the vehicle and the mechanic accidentally dropped it as she moved it out of the way, your claim would almost certainly fail. But if your smartphone videoed the mechanic deliberately kicking the phone around the service bay, the dealership would be liable for their employee’s conduct and your consequential losses. (These are just examples and are not implying anything is amiss with this particular dealership, I hasten to add)

This and other such “unfair” terms (only a court can rule on the fairness, or otherwise, of the terms) abound in contracts. Once you start looking, you’ll be amazed at how common they are. There’s nothing to stop a contract being drawn up with such terms and also nothing to stop one party trying to apply the terms. But once a party asks the state to step in and enforce the terms, nation states can and do set limits on what they are prepared to sanction.

Unless all parties to a Smart Contract are genuinely stateless – a domain which is impossible to create in practice – the common law of the state still places restrictions on what are valid contractual terms.

Conclusion

Readers will hopefully appreciate that I have tried to write this piece “straight” and taken the claims made for Smart Contract platforms such as Ethereum as their champions make them out to be.

But given the obvious limitations to the premise for a Smart Contract, as outlined above through the explanation of the principles of unjust enrichment and unfair terms, it has been demanding to achieve the levels of cognitive dissonance required to believe that the platforms themselves – and their admirers – are for real. At times, it has felt like it was more a job for our Richard Smith to highlight some cunning-but-ultimately-obvious scam. And yet this is not your typical New Zealand-based boiler room fraud or Carbon Trading shady dealing.

Richard Smith summed it up thusly:

The potential of libertarian paradises to terminate in a big fraud is always obvious and always stoutly denied by the fanboys (or shills).

In the case of Ethereum, is the user option to steal the money a bug or a feature? Ethereum and bitnation [another Smart Contract platform] seem in their more or less specialized ways to be quite close to a cyber version of the Freeman on the Land hoax. That word Sovereign again. People who want to opt out of taxes, states, citizenship.

All of which got me thinking about a different, but related conundrum. I’ve been banned (if only informally!) by my friends and family from walking alone in New Age district of Brighton (part of the City of Brighton and Hove, a coastal resort situated in East Sussex, England). The reason is that I am simply too much of a sucker to be safely left to my own devices. My crown chakra is a little dull? Oh, I can see why I need that £25 meditation charm then. And this £50 healing crystal will deep cleanse my aura will it? Oh, okay, I’ll take it.

My problem is, I really want to believe. That makes me all-too-readily an easy mark. This subject was covered in-depth in a rather good podcast by Cardiff Garcia in the FT Alphaville team whose guest explained the psychology of cons and how one of the prerequisites for executing a successful scam is that the scam-ee starts from a basis of wanting to believe in the hucksterism of the would-be scam-er.

If you are sufficiently self-aware, you can begin to know your own limitations and take steps to overcome them. It’s difficult. Trusting others to tell you the truth and then actually listening to them is one part. But first you also have to find people who are willing to speak the truth to power (or, if not power, to your own ego).

On the contrary, if you’re an omnipotent central banker, a self-appointed Master of the Universe investment genius, or a CEO who is not only paid tens or even hundreds of millions a year in compensation, it’s borderline impossible to not end up spending some of that money on a coterie of flunkies who’ll only ever tell you how great you are. Either that or your position simply attracts sycophants like moths to a flame.

Unfortunately, there’s no shortage of charlatans asking you to sell your cow for a handful of magic beans.

Of course, our elites are all smart enough not to fall for blatantly obvious scams or be lured into malinvestment, right? And in no way is executive compensation misaligned into pursuing short-term valuation ramping based on get-rich-quick schemes? Good, we’re all alright then.

So, even Goldman can be scammed! Good to know.

The Letter of Credit (L/C) business and Ethereum.

The L/C business only solved the problem of payment, assuring a supplier would be paid, and not so much preventing fraud from the supplier. Under ICC400 rules, a banker is to simply check that the documents submitted on their face appear to be original and that they state what is required in the document, and then the banker was obliged to pay, and buyer’s ability or intent make good his payment is the banker’s problem, not the suppliers.

What made L/C really work in areas where trust of the supplier was limited was not the bankers (as the banker’s job was mostly to show that the buyer was solvent), but rather was the provision for a document from a trusted 3rd party check.

For bulk/non-containerized shipments, the ship owner’s bill of lading(b/l) would be an indication of the weight and/or volume shipped (but usually not the quality). As to Containerzed shipping, The shipping companies B/L is nearly useless as a check on what’s in the 20’/40′ box.

Eventually ship surveyor, originally hired by insurer’s to check the condition of a vessel before a voyage was underwritten, began to offer a third party service to check the quality as well as the quantity of the cargo (also being underwritten) to prevent fraud. They evolved into survey companies like SGS, Norse Detske, CICC, etc provide inspection certificates, and it’s this documentation, and the trust in the integrity, technical competence, etc of the surveyors that write them that help prevent buyers (and banker’s) from being defrauded, I don’t see how any magic contracts can possibly provide this same protection for buyers without involving a similar, expensive and heavily reputation sensitive infrastructure that takes years to build up and seconds to destroy.

(Goldman Sacs is certainly planning to carry out scams all the time, if they are pumping this, it’s to off load it on suckers).

Whoops, showing my age. ICC400 is now ICC600.

BTW, I’d love to see how “Force Majure” term is put into the algorithm. Defining what is an Act of God in code is going to take some nasty chops.

Yes, indeedy. Had a mind lapse there about Goldman!

That is not correct. For certain locations and suppliers, no one would every rely on a mere bill of lading. Documentary LOCs are the norm. There are often 15-20 separate documents in a documentary LOC. Even oil shipments are subject to documentary LOCs (there have been cases of people being conned with oil and poorly conceived documentary LOCs, a famous case of relying on a dipstick test at the shipper floated petroleum on top of a heavier, cheap fluid. I can’t recall, but it might have been salad oil).

If you Google, you can see plenty of banks offering documentary LOCs:

http://www.citi.com/slovakia/commercialbanking/english/da.htm

I agree that documentary LOCs are not the best solution for certain types of goods (and make no sense for regular, trusted shippers), but to assert that they were not very widely used and not used now is flat out wrong. The analogy is to the Ethereum case: parties new to each other, no or not much basis for trust, one party wants other to do certain things before getting paid and needs that verified.

Citibank has a ton of business with US multinational due to its international cash management platform, GTS. It’s seen as the best in the industry.

Bill of Lading and an invoice, perhaps a cert of origin for customs purposes, are often the norm when the supplier is considered trustworthy, for example with a commercial contract (vs. the environment, a different issue) I’d trust Exxon Mobil, trust them more than Goldman Sacs, and just about as much as I’d trust SGS or most courts, which can be corrupted too. However, what I wrote earlier included:

Maybe I should have written “documents” instead of “a document”, but it’s fairly normal in international trade to just have one surveyor report. I’ll add to no surveyor, and no court is fool proof protection against a purposed fraud, and anyone buying a bargain from a supplier they absolutely can’t trust gets what they deserve for their greed.

No where did I say L/C’s are unpopular. Indeed L/Cs still form a significant business for the big banks in Hong Kong. A great deal of their short term finance business is underwriting margins on L/Cs (or forfaiting – another reason Etherium is redundant), Financing trade built HSBC into a giant. Their ability to correctly assess margin risk for L/Cs world-wide was a distinct advantage over almost any other bank, that is before they got excited about the margins in washing drug money, graft, etc; and started to ignore this steady but boring source of income. L/C fees are our largest banking expense, but we stopped doing business with them because of their money laundry activities. It has been a huge pain because there is no one bank who can step into their shoes on L/Cs everywhere we do business.

Etherium, what a name for a scam, because one day it’s going to go poof and disappear into the Ether with the funds. The psychopaths behind this must be laughing themselves silly at the rubes. BTW, Yesterday, this page was the hardest to access due to the DDOS attack, could they be the sponsors?

The heavier liquid was water, seawater to be precise. Inexpensive and widely available.

Haha, my recollection was water but this is a story I heard 30 years ago, and I recall salad oil being used as an oil substitute from another case…I should have checked the specific gravity!

Absent a precedential code of conduct and recourse, trust in trade would quickly dissipate. Without trust, there is no trade. If the Ethereum paradigm takes hold, I would expect the demand for survey companies to explode. This approach seems dumb and dangerous.

Great post. Even I was able to follow it (I think). Perhaps it’s time to stipulate that when someone puts “smart” in the name of their product or argument (example: Hillary’s “smart power”) it’s time to run for the hills. In the dull old days there was plenty of fraud but at least the term “honest businessman” was one of the highest forms of praise.

Today’s elites practice nihilism and then wonder why the world seems to be falling apart. This is not “smart.”

+1

I’d add my own nomination — “smart bombs”.

Off topic, or not, I have seen signs like those that are actually legal advice masquerading as a contract. “Proprietor can not be held liable for damage to vehicles caused by shopping carts.”

“Can not” also implies “can”, the message is trying to seem to state a contract requirement, while actually affirming conditionality.

“But Amazon moving into grocery delivery is another example of big corporations either sitting on cash piles they can’t sensible spend or else have access to funding at almost zero cost ploughing the money into implausible projects.”

I know its nitpicking, but grocery delivery is the future. It makes more sense in every way: its more efficient, it (eventually) gets rid of retail stores, gets rid of the time spent driving to a market, and is increasingly popular. Instacart, the San Francisco company, accounted for ALL of Whole Food’s gain last quarter. Eventually, I see grocery delivery as a way to keep goods fresh for longer periods of time, since produce can be kept in a dark fridge instead of displayed (& sprayed) in a store for a day before its all thrown out.

A more apt analogy of companies “sitting on cash, not knowing what to do” would be Apple entering the car market. What a joke. Not only is the market super saturated already, but Apple will have to rely on the components built by all the suppliers that already supply for Ford, GM, Chrysler-Fiat, etc. Talk about redundancy…

I agree to the degree, certainly in rural areas. Even if there is a store, it will be subscale and at the end of a long supply chain. Unfortunately rural areas are les profitable for delivery than urban areas and less likely to have coverage. Conversely everyone wants to cover urban areas where a conventional supermarket format store still makes a lot of sense.

My own experience is also that fresh produce can be very variable with delivery services. Sometimes it is way better than is typically available at the market (because it comes from a high-volume high-turnover centre). Sometimes though it is clearly a load of rubbish at the very limit of the use-by date and i’d never have bought it. But of course you don’t know that until it’s on your doorstep…

But people like to shop and discover new items.

Plus, I don’t think it will work outside of cities where people work 14 hours day at high salaries.

Great post. Thanks so much.

The real story on Ethereum is the hubris, they raised $18M in Bitcoin and promptly decided they needed to write a brand-new language, a brand-new VM, and a brand-new browser. Just writing a new language is extremely non-trivial and these guys bet the farm and their new algo on it. Then they raised $150M in a crowdsale based on the stuff they wrote. Now that it has failed, they are committing Blockchain Mortal Sin #2, they are adjusting the values on the “immutable” ledger to abscond with the funds taken by the person who discovered a flaw and executed a “smart contract”. $50M worth, ouch.

Next time the script kiddies need to take Econ 101 and pay special attention to the terms “moral hazard” and “natural monopoly”.

Crumbs, I hope that gets widely published. How awful!

The link to the Maria Konnikova podcast about cons requires registration. Here’s a link to another podcast by her on the same topic (the psychology of scams) that doesn’t require registration. Including how to scam-proof your life.

Excellent post. The review of some points of contracts is especially refreshing (in more senses than one). And unfair terms are widely used to explicitly or implicitly coerce parties to be subject to terms that they do not have the resources to bring before a court, even when those terms would be indefensible in a court.

But I have to disagree to some extent; virtual/”smart” contracts may claim to, and would very much like to be, independent of region or jurisdiction, but they are not. They are subject to the electronic and software infrastructures, the computers and networks, within which they exist. Virtual contracts move the jurisdictional enforcement of contracts from nation states to service vendors (be they banks, investment traders, payment processors, or frankly anybody who sets up a host system with sufficient resource capacity for commercial operation, or at least the appearance of operation). This is of a piece with the push towards ISDS courts, by which corporate entities can circumvent national laws, and even the enforcement of contracts engaged in and protected by nation states.

ISDS still requires nations to enforce contracts. What it takes advantage of is that most nations are dependent on clearing dollars in NY, and by using this leverage they can ignore all but the US legal system, which ISDS would make phial servant of large multinational corporate interest above all else. By putting a death grip on the finacial health of any single nation, they can beat most of them into submission.

Iran, North Korea are possibly two examples of both bucking the system, and the cost there of.

I believe the value of Etherium or Bitcoin is in the blockchain. The ledger of things will be one of most cost saving, disintermediating technologies of the 21 century. Law will be one of the most refreshing things that will be disintermediated. Safe, public, and efficient ways of organising our society to level the playing field in so many ways. A good book on the subject is “Blockchain Revolution” by Don and Alex Tapscott. I am a doctor and the only field I know that has been more Rub Goldberged is the legal profession.

Are you confusing the issue of elite appropriation of power through a monopoly on either knowledge or an ability access to knowledge (which I’ll grant you is a legitimate concern) with the unavoidable limitations in the spread of knowledge?

If so, this problem will need to be resolved by removing the elites’ ability to exploit the unavoidable scarcity of knowledge. It cannot be resolved by a completely implausible notion that increasing the supply of knowledge (you call it disintermediation but that is what you are implying) will reduce the leverage of those who can put in barriers to inhibit the people who need to access that knowledge from obtaining it.

Your argument sounds akin to a situation in which your bath floods at 10 o’clock at night. You call some plumbers in the local area, they tell you their night rate is $100 an hour with a $150 minimum call out charge. You revile the trade for their “exploitation” of you in a predicament and instead decide to ask your neighbors in your street or building in for help. But none of them are plumbers. What you needs is the skill set of a plumber, not well intentioned but amateurish advice which might resolve your problem but then again might just make an even bigger mess than the one you already have.

If you haven’t built up goodwill with a plumber who might be persuaded to attend a call out at an unsociable hour at the standard rate, you have to pay to reward the person who has developed a specialist skill and is willing to forego family / rest time which other similarly skilled people don’t want to give up. We are all though able to foster our own relationships with others and you could have instead cultivated a long-term association — friendship even — with a plumber (or any other person who possess a skill). But then you would have had to invest in making sure that you’d given all your plumbing (or other) tasks to this person, paid promptly, not given misleading descriptions of the work you need and so on.

Now, there is another legitimate problem of rogue operators who charge fees for a bad job. But the best way of resolving that problem is to set appropriate standards in whatever field is susceptible to a rogue operator getting away with “selling lemons”, effective regulation of those standards and enforcement of them. You can also impose caps on excessive fees — although you need to watch who is seeking to do that and what their motivation is.

But you can’t complain about exploitation of others by unscrupulous operators then proffer a solution which is in effect an appeal to be allowed to get something for nothing.

Amen!

Disintermediating “the law”, OMG. I for one am not interested in the time tax neo-liberals know we can’t pay and that they don’t have to pay because privlige. Only a stupendous ego would find this interesting.

What is freedom today? Slavoj Žižek

” Law will be one of the most refreshing things that will be disintermediated. Safe, public, and efficient ways of organising our society to level the playing field in so many ways. A good book on the subject is

“Blockchain Revolution” by Don and Alex Tapscott“ ” Lord of the Flies” by William Golding.There, fixed it for you.

(Guffawing while trying not to be spitting out his mouthful of tea)

+1

The problems at Ethereum are much worse than this. They are trying to build a digital property rights/banking standard and they don’t actually know anything about the laws that have evolved to protect these rights because they’re too stupid to understand the nature of property, money, banking – and, as you point out, contracts.

They just had $50 million in their little digital coins hacked and it apparently never occurred to them that they were dealing with a “valuable” product, that someone might try to misappropriate it or that they would need procedures to find and return stolen goods to their *rightful* owners because they had never sat down to consider what rights themselves are or why money would possible be valuable or worth stealing.

They wanted to create a bank without guards, without police to track down stolen property or judges to, you know, judge the guilty from the innocent.

Why?

I can imagine Blythe Masters or someone like her vested in the brain washing/spin dry techniques of the Chicago School of Economics telling them white collar fraud can’t possibly exist because, you know, why would a corporate defraud itself?

1) Corporations aren’t people. They aren’t actually conscious nor do they form their own intentions. They are institutions created by various actual persons to further a (possibly cooperative but differing) agenda of said persons.

2) Money is valuable. In a strange way, the Chicago School is filled with Communist sympathizers because it doesn’t believe money can be stolen because it doesn’t believe that money is valuable. Only by devaluing someone else’s money (or someone else in general) can you possibly justify stealing it – or at least hiding the theft. In their minds fraud can never exist. That’s the purpose of their religion. Their beliefs deliberately blind them to the white collar theft of the new aristocracy/kleptocracy.

Liberty is the responsible exercise of self-government. It isn’t just your freedom to do something but also your obligation to do it well, on behalf of a better society. You don’t, for instance, have a protected right to lie and commit fraud under the First Amendment because of the damage that does to your fellow citizens (though the Supreme Court said as much in tossing out the Virginia Governor’s fraud conviction this week; say hello to right of petition “fees”).

Computer security vendors are sloppy and uncoordinated and thus always wriggle out of accountability for their shoddy products. These product flaws only get worse in a liability-free environment. This is one of the many adverse changes that came from shifting software from a product with liability to an unregulated service back in the 1990s. In this context they have lucratively combined computer software product liability fraud with the madness of banking deregulation criminogenic fraud. (If Bill Black fails to grasp anything, it’s that he doesn’t have nearly enough time to catalog all the perverse forms of agent-loss occurring throughout the economy today.)

Ethereum coders are providing a utility for digital banking transfers and their ideology absolutely won’t permit them to consider properly the issues of bank regulation, utilities or the captive markets creates by monopoly standards. If they knew any of this and if they had a conscience then they couldn’t extract monopoly rents with their first-mover advantage – which appears to be the ultimate purpose of their exercise.

What they’re trying to do here is hijack an essential function of government – which the government itself won’t do because it’s being controlled by the same interests trying to privatize these exact public goods. The last thing these people want is a strong government protecting and defending the people’s valuables.

You also can’t talk to these digital anti-liberty libertarians about other people’s rights around your property. You can’t talk about theft of copyrighted goods being bad for the market or browsing or criticism rights that consumers might need even in a strong property rights regime (analogous to rights of way issues with real estate law). You can’t talk about the resale of digital goods like iTunes songs. In the Uber economy your property becomes their rental to you.

In other words, you have people creating a property rights in an environment where they don’t actually understand the concept of “people” or of “rights.”

How many at Ethereum have read Rousseau? Locke? Hobbes? Adam Smith? Montesquieu?

If I seem familiar with these matters it’s because I pointed out all of this in a editorial on “Telerights” more than twenty years ago for BYTE Magazine and other venues. Two decades later they tried to cobble together something called “Ultraviolet” to address some of these issues. Many of us are tired of waiting for the computer industry to wake up and discover economics, law, political theory and other important subjects…

Informative and well said.

I suspect most of them have not even finished reading the Ayn Rand junk literature on their e-readers. They’re like most owers of the Bibles, or Mein Kampf. The awful dreck is on the shelf or their Good Reads Account to mark their party loyalty, at best they just assume it says what they’ve been told, and it wouldn’t matter an inch to them if it didn’t.