By Suresh Naidu, Associate Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Columbia and Noam Yuchtman, Associate Professor, Haas School of Business, UC-Berkeley. Originally published at VoxEU

Today’s labour market in the US has much in common with that of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Then, as now, there were few government protections for workers, fears over cheap immigrant labour, rapid technological change, and increasing market concentration. This column explores the lessons that can be drawn from the earlier ‘Gilded Age’. The findings suggests that even as markets play a greater role in allocating labour, legal and political institutions will continue to shape bargaining power between firms and workers.

Phenomenal increases in income and wealth inequality in the US and other rich economies have been observed over the last four decades, driven by skill-biased technological change (Autor et al. 2008), increased trade (Autor et al. 2013), and institutional and policy changes that have allowed the rich to earn/extract a greater share of the economic pie (Alvaredo et al. 2013, Piketty 2014). An associated rise of populist politicians suggests a link between economic inequality and political polarisation (McCarty et al. 2006, Autor et al. 2016), and potential for costly conflict (Esteban and Ray 2011, Bowles and Jayadev 2006).

Moreover, there is every reason to believe that past trends will continue –technological change seems to continually enhance the return to capital and the earnings of the most skilled (while displacing the less skilled); it is increasingly easy to hire workers across borders in online labour markets; and greater numbers of workers are now part of the ‘gig economy’, with employment relationships replaced by contractor relationships offering workers limited collective bargaining rights and fewer legal protections (Horton 2010, Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014).

Remarkably, looking ahead towards the labour market of the future feels a lot like looking back at the labour market of the past, particularly that of the late 19th and early 20th century ‘Gilded Age’ in American history. Then, as now, few government protections for workers existed, save those they could secure for themselves; then, too, native-born low-skill workers felt threatened by cheap immigrant labour from abroad while being buffeted by rapid technological change and increasing market concentration. Labour market outcomes in the modern world also resemble those from the early 20th century – the Gilded Age was the last time such high levels of economic inequality were observed in the US.

If labour markets are going ‘back to the future’, the study of historical labour market institutions can provide useful lessons for the modern world. In recent work, we study labour markets in the American Gilded Age, answering two questions of historical importance, but also of great relevance for understanding contemporary society (Naidu and Yuchtman 2016). First, if labour markets look increasingly like laissez faire textbook models, does conflict over labour market rents, and thus the distribution of income, necessarily go down? Second, in the absence of labour market legislation, which institutions regulate and manage labour market conflict?

The American Gilded Age labour market came extraordinarily close to the archetypical labour market taught in Economics 101 (Fishback 1998). One might think that in a world without regulatory red tape, the labour market would simply equate supply and demand, establishing a ‘market wage’ for a unit of labour, eliminating non-competitive rents, and diminishing the stakes from conflict. One might further assume that in such a world, the institutions resolving such conflict would be irrelevant.

However, we provide evidence that despite the lack of regulation, economic frictions in the labour market generated rents, and costly and violent conflicts over these rents were pervasive. Rather than giving rise to efficient allocations, the unregulated labour market generated militant and coercive labour movements and employer organisations, and led to increased allocation of resources toward the domestic policing and military capacities of the US government.

Our approach to studying frictions in 19th century labour markets is to use the 1850-1880 national samples from the 19th century Census of Manufacturing (collected by Jeremy Atack, Fred Bateman, and Thomas Weiss) to test for firm-specific wage premia. While it would not be surprising if the value added of firms were correlated with wages across markets, in a perfectly competitive market there should be little variation in the wages of observably-similar workers across firms within the same labour market, at a single point in time. Put simply, in a perfectly competitive labour market, similar labour sold in the same labour market should sell for a single price.

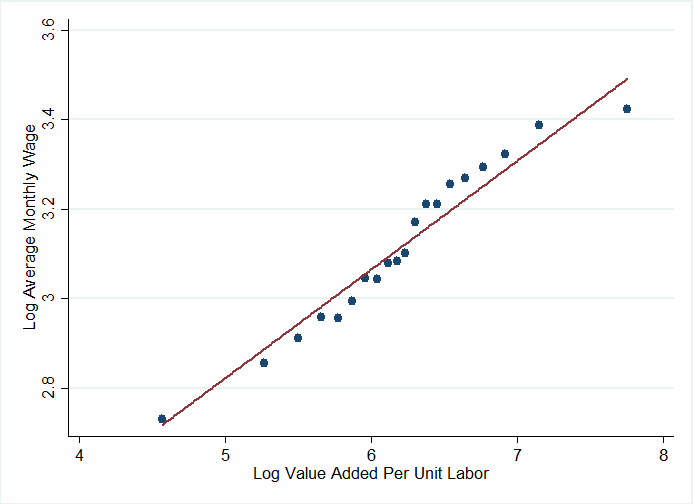

In the left-hand panel of Figure 1, we plot firms’ wages against firms’ value added per worker, along with the best-fit linear relationship. One can see that, unconditionally, higher value added firms paid higher wages. To more directly examine differences in wages across firms that ought to be competing in the same labour market, in the right-hand panel of Figure 1 we show a scatterplot of wage residuals, conditioning out the city X industry X year fixed effects, against value added per worker residuals. This plot compares wages and value added within the same city, within the same industry, within the same year, and one continues to see a strong, positive relationship between firm value added and wages.

Figure 1. Wages and added value, 1850-1880

Notes: Figure shows binned scatterplots of firms’ log average wages against log value added per worker. Left-hand panel shows unconditional values. Right-hand panel absorbs city X industry X year fixed effects and plots residuals. Firm-level data on wages and value added per worker are from the national sample of the Census of Manufacturing 1850-1880 collected by Jeremy Atack, Fred Bateman, and Thomas Weiss.

In assessing the relationships in Figure 1, one still might be concerned about some omitted variable associated with both firm value added and wages. To mitigate endogeneity concerns, we use within-labour market variation in output product prices as an instrument for firm value added. Using this instrumental variable approach, we continue to find a significant, positive relationship between firm value added and wages within a local labour market. Note that this is consistent with recent work on contemporary labour markets – indeed, our rent-sharing elasticity is estimated to be 0.147, which is remarkably similar to estimates from contemporary data (Card et al 2016).

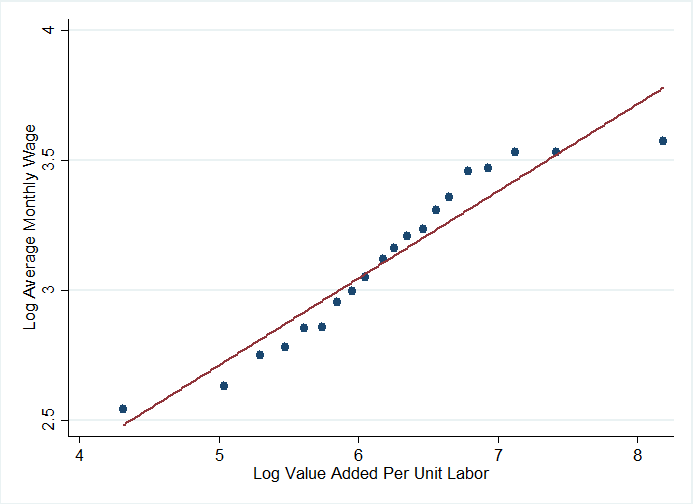

These findings suggest that firms matter in determining wages, and thus that firm-specific strikes could affect workers’ pay. Consistent with this is the occurrence of fierce – sometimes deadly – and frequent strikes throughout the 1880s and 1890s (see Figure 2). Also consistent with this is evidence we find of a significant, positive correlation between the occurrence of a strike and worker wages at the firm level (controlling for a wide range of firm characteristics), based on historical data in the ‘Weeks Report’ (1886).

Figure 2 Number of work stoppages in the US

Notes: Figure shows time series data on the number of work stoppages in the US (series Ba4954 from the Historical Statistics of the United States), the number of violent labour conflicts, and on the number of deaths occurring in labour conflicts (both from Turchin 2012).

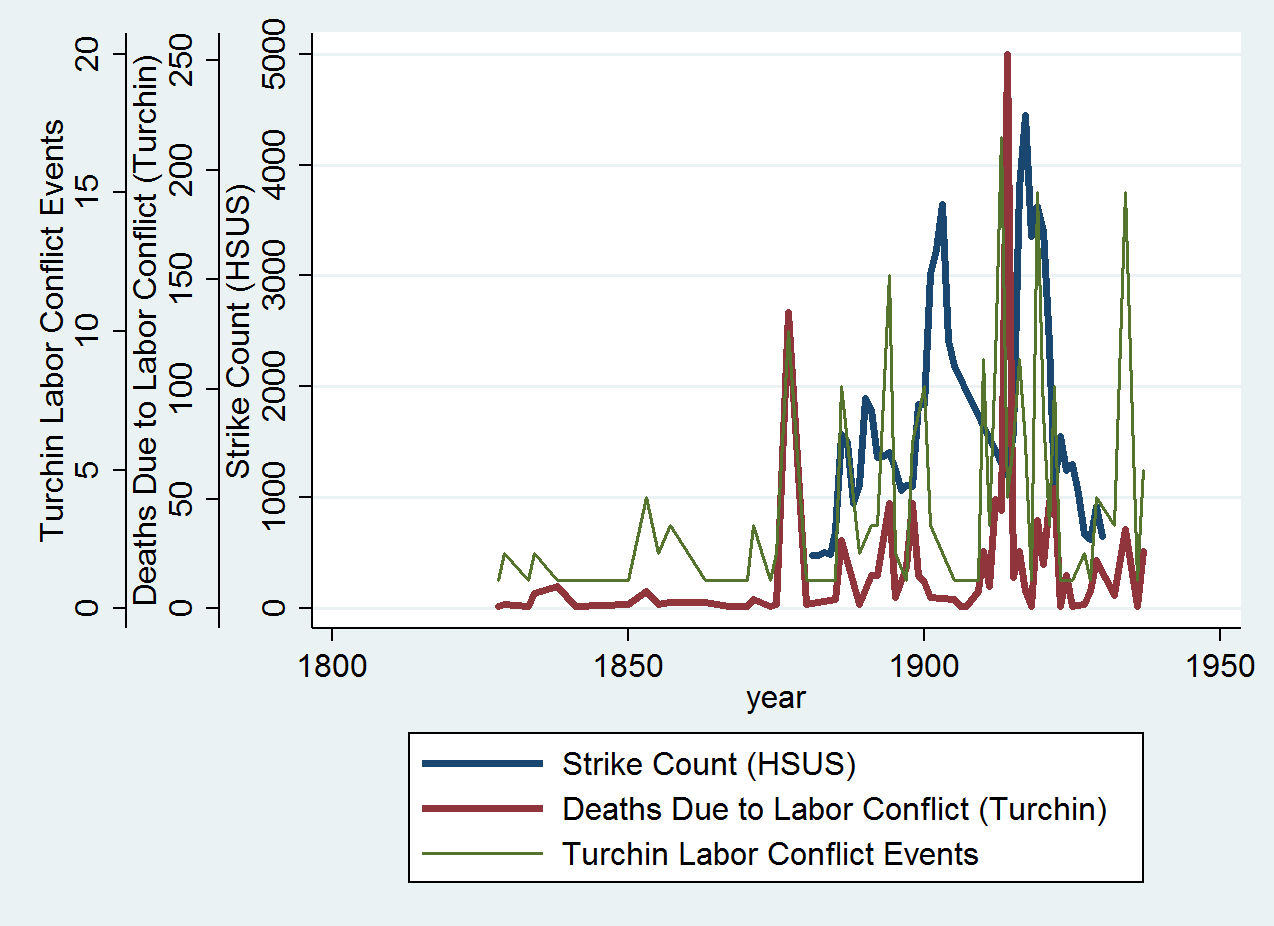

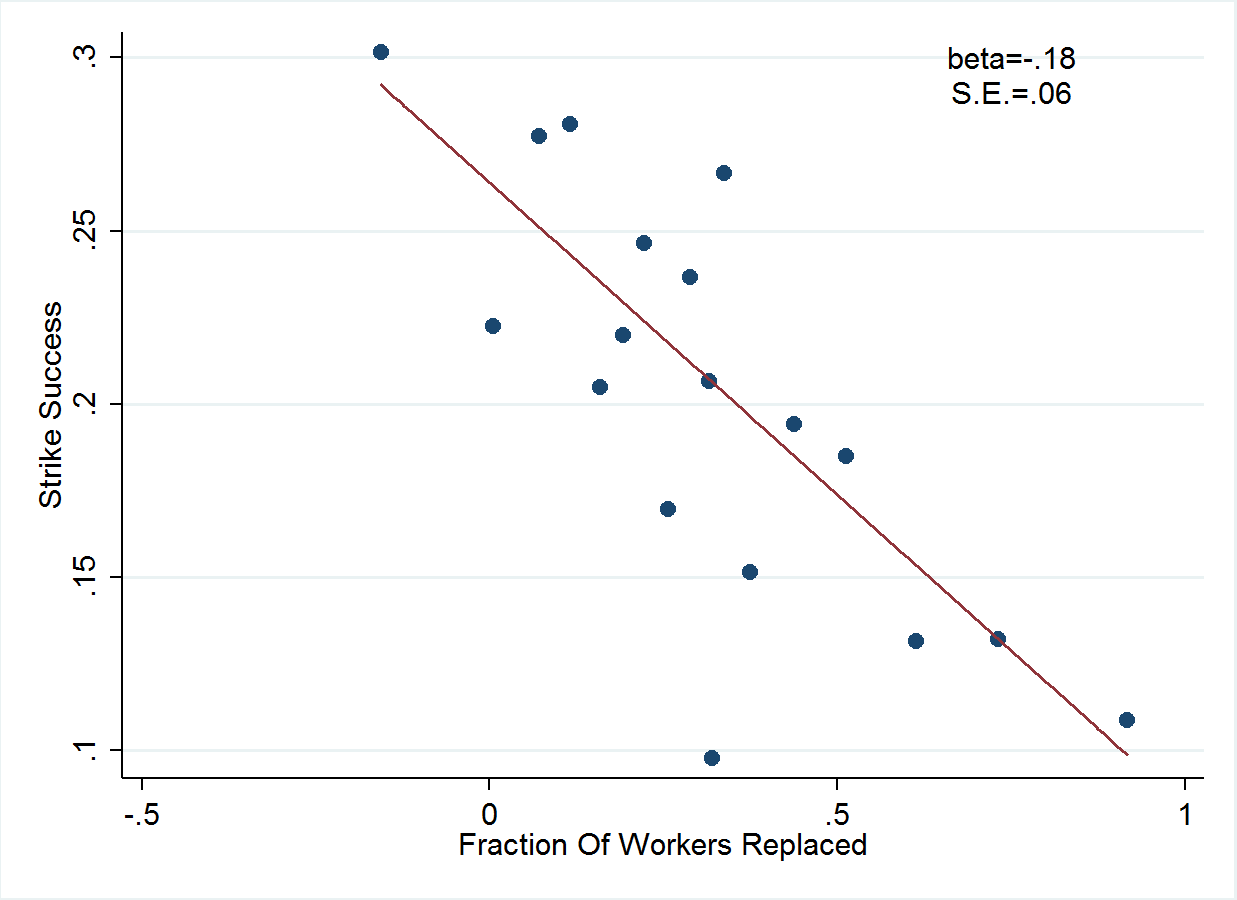

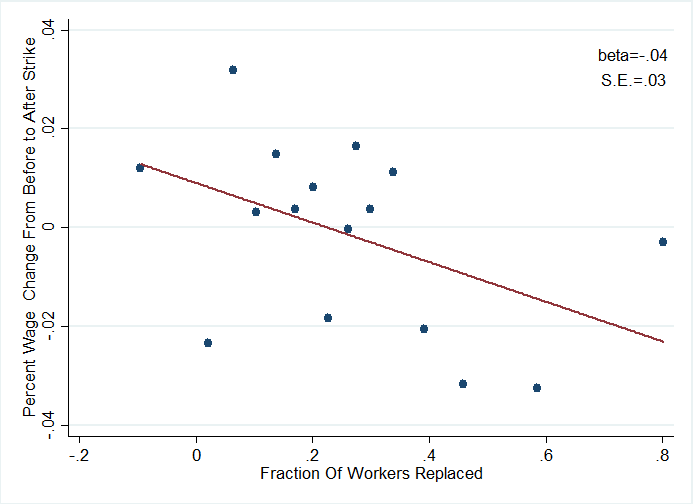

US Commissioner of Labor data (from 1888 and 1896) reveal that a key feature of successful strikes was the ability of incumbent employees to prevent the use of replacement workers, via persuasion, pickets, or violence. One can see this in the left-hand panel of Figure 3, where we plot the (negative) relationship between the success of a strike and the use of replacement workers (conditional on city and year fixed effects, as well as the log of employment at the firm in question). In the right-hand panel of Figure 3, we show that wage increases resulting from strikes also depended on strikers’ ability to prevent the hiring of replacement workers. Given these stakes, it is unsurprising that employees were willing to use physical coercion, when necessary, to try to prevent the hiring of scabs.

Figure 3 Replacement workers and strike outcomes

Notes: Replacement workers and strike outcomes, for strikes with a positive number of replacement workers. Left panel plots residualised strike success dummy variable against residualised fraction of replacement workers hired. Right panel plots residualised change in a firm’s wage bill (post- minus pre-strike) against residualised fraction of replacement workers hired. Data come from the Third and Tenth Commissioner of Labour Reports.

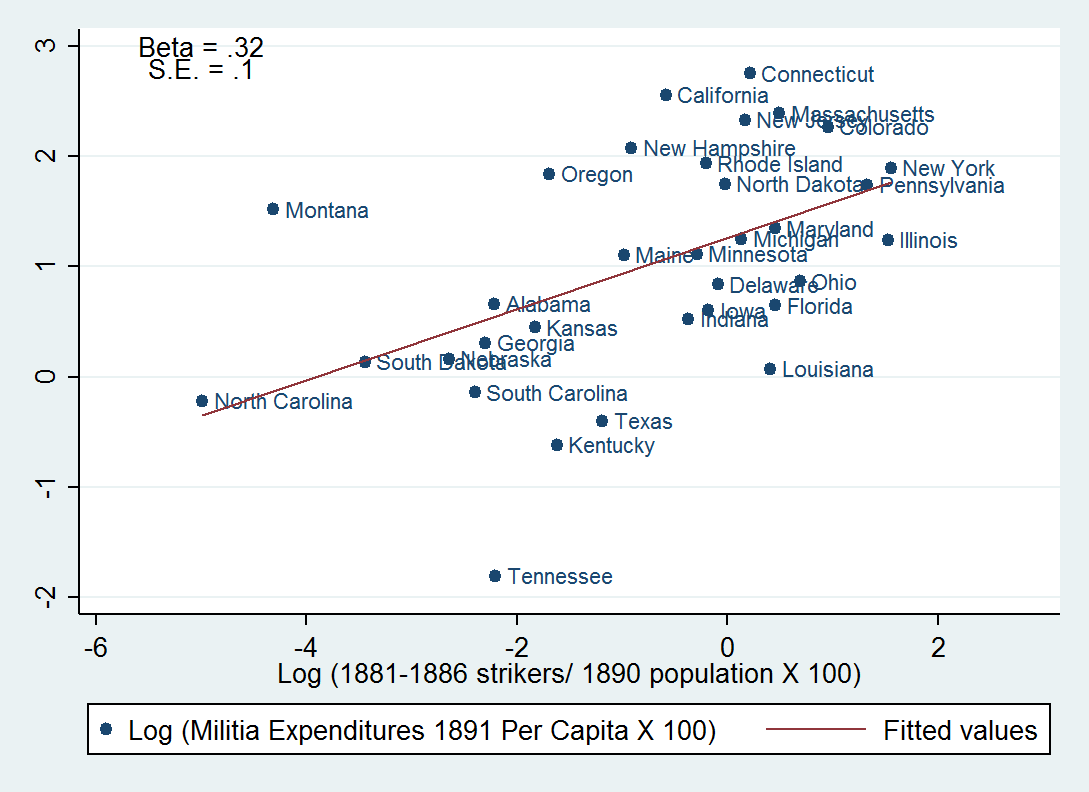

Employers, too, understood that breaking picket lines was crucial, and they responded to striking workers’ use of force with coercion of their own. This was often accomplished by enlisting the power of the state. Riker (1957) shows that between 1877 and 1892, the modal use of state militia was in response to labour unrest. In Figure 4, one can see that state resource allocation was affected by labour unrest: the frequency of strikes in the late 19th century was significantly, positively associated with state militia expenditures.

Figure 4 Militia spending and strikers

Notes: Militia spending and strikers. Figure plots the log of militia expenditures per capita against the number of striking workers per capita, by state. Data come from Riker (1957).

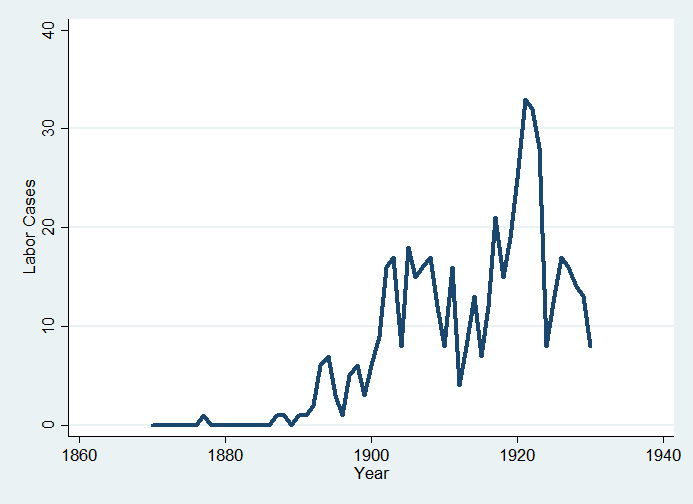

Government intervention on the side of employers was supported by the courts, particularly following the adoption of the judicial labour injunction as a legal tool to prohibit strikes. Figure 5 shows that injunctions increased rapidly beginning in the1890s, occurring most often during the period of greatest labour conflict.

Figure 5 Injunctions against labour disputes

Notes: Figure shows counts from Lexis-Nexis and Westlaw, based on a search for “injunction” and (labour OR strike OR workers OR collective bargaining OR combination), and reading of cases to ensure that injunctions were issued in response to labour disputes.

Looking around today, it is obvious that inequality and conflict over the distribution of wealth and income remain salient a century after the first Gilded Age. History is never a perfect guide, but the late 19th century suggests that even as markets play a greater role in allocating labour, legal and political institutions will continue to shape bargaining power between firms and workers, and thus the division of rents within the firm. What remains to be determined – and battled over – is which institutions are empowered to act, and whose interests they will represent. Regardless, latent labour market conflict seems likely to be a prominent feature of our new Gilded Age.

See original post for references

– This was often accomplished by enlisting the power of the state. Riker (1957) shows that between 1877 and 1892, the modal use of state militia was in response to labour unrest.

+ Figure 4 Militia spending and strikers

Tennessee as an outlier got me thinking, the regression line looks like it correlates to urbanization. As time went on, police took over the function of suppressing unrest, but the time frame of Fig 4 predates establishment of police forces for most of the country.

The question then is what data points indicate labor unrest beginning in this era? Is there any indication of economic insecurity that will push workers towards strikes and violent opposition of employers conditions?

I keep thinking of how seemingly weak the supply chains of manufacture are as a point of weakness in employers control over labor. Just in the last month I learned that a small supplier in my town could have brought automotive production at GM to a halt (GM avoided this through court action and taking over the tooling machines from the bankrupt supplier):

http://www.detroitnews.com/story/business/autos/general-motors/2016/07/13/supplier-asks-bankruptcy-judge-end-gm-contracts/87036310/

Volkswagen is facing it’s own problems related to corporate malfeasance. To try and keep the ledger book clear, VW is trying to squeeze suppliers. One such supplier refuses to be squeezed and told VW that they can shove it and not have their parts.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-08-22/vw-restarts-talks-as-supplier-feud-expands-to-golf-production

Many of the press articles called this unprecedented. What it points out to me is that lean manufacturing has made these giant companies extremely vulnerable to labor shocks. I would suspect this is the case throughout markets where things are manufactured and shipped (Amazon for example).

But the question remains over what will tip workers into revolt?

The weak supply chain you describe was described in detail in Barry Lynn’s book “End of the Line: The Rise and Coming Fall of the Global Corporation”. I too have wondered why workers haven’t taken advantage of this vulnerability. The IWW Sabocat is named for the two worker actions unions were constructed to control. I don’t understand why this has been forgotten — or maybe it hasn’t. If workers were making advantage of the weak supply chains I doubt it would be described in any of the news media. The way the Patriot Act is written I believe such actions would be treated as terrorism — so I doubt the workers would advertise such action. As for your question “what will tip workers into revolt?” — I’m afraid that could happen at any moment with disastrous impacts on all of us. Barry Lynn worried that the US supply chains are so weak and extended they could collapse simply as a result of a natural event.

In my experience as a worker, they don’t take advantage of this weakness because they have to eat, and they don’t know about it. Most of them are too busy trying to just survive in my experience. This is where a good “ground game” could make a real difference a’la Sander’s Revolution. Basically, get the word out and have some kind of material support for these people when they decide to pull the trigger.

Good point!

Extrapolating further — attacking the supply chain requires a considerable amount of knowledge that’s probably spread across several people in any given organization — people who are not workers. If the source for an attack were caught anyone who helped would be treated as co-conspirators and all would be treated as terrorists.

The only alternative I can think of ends up back in the streets. That time may come and I want to be far away when it does. I am beginning to doubt the U.S. government would be any kinder or gentler to American citizens than they are to foreign nationals — in their own countries.

Who would have thought…. Laissez Faire created a Gilded Age last time we tried it, but this time, no one could have seen that coming… or notice when it happened…. or figure out why. Is stupidity a prerequisite for power?

This was the advertised policy. GHW Bush in a post-defeat Atlantic interview stated that the goal of GOP policy had been to concentrate wealth in tighter, righter hands. Since the Powell memo, since the Banker’s coup, since the square deal and the new deal the tension between the wealth elites and the teeming masses has ebbed and flowed.

http://www.almartinraw.com/public/column398.html

The authors are pretty sold on the meritocracy theme, insisting that all workers in the upper echelon are highly skilled and thus explaining their well being, leaving out numerous asymmetries such as nepotism and legacy treatment where those with wealth use it to create class divisions with the intent of protecting their own. Among the high skilled work force are high skilled people, certainly not all of them, and there are plenty of high skilled un/underemployed, how do the authors deal with this phenomenon? Another quibble but not specific to the article is that workers today are fragmented compared to factories with many workers and organizing has been engineered out of the equation with global free flow of capital.

Is in my opinion the single most important point. When the government (of the people) instead is acting like the government for big business then the result will be what we see today. The more preference that is given to the interests of big business, the less legitimate the government will be seen to be. The so called ‘populist’ movement is the last hope to avoid another less peaceful change.

We’ll see if ‘but the gdp is growing’ argument can keep people from demanding change.

Spot the difference:

1920s/2000s – high inequality, high banker pay, low regulation, low taxes for the wealthy, robber barons (CEOs), reckless bankers, globalisation phase

1929/2008 – Wall Street crash

1930s/2010s – Global recession, currency wars, rising nationalism and extremism

Trick question.

For the globalisation project they chose to resurrect neoclassical economics.

First time round:

Huge inequality, Wall Street Crash of 1929, The Great Depression

Second time round:

Huge inequality, Wall Street Crash of 2008, global recession

They didn’t bother to fix any of its problems in the mean time.

OK, who were the experts responsible?

Remember that Keynesian interlude when we had the lowest levels of inequality in the developed world.

It all seems like a distant memory.

Thank you for this post (and those who have commented)

So, Laissez-faire didn’t work so well – shocker (don’t all games require rules/referees?) But, can we all recognize that different challenges arise with people organizing too – strikes can shutdown a business and “negotiations” can ultimately tax other people (public pension crisis.) There’s a balance – somewhere – between the two that I do think exists and could bring forth more sustainable growth for everyone. Is a proper dialogue possible? Is such a dialogue safe from injunction or violent rhetoric? Hmm…

http://www.letsalllearnhowtofish.com

That’s how you can learn more about my straw-man; please hesitate before lighting a match.

Skilled workers in plants (can not only halt production but also be seen as leaders) vs just-in-time manufacture, the ability of one supplier, ie the workers of same, can strike and halt production. But will their action have the same generalized affect? Or will they be easily characterized as greedy and causing disruption, i.e. loss of income for the workers of the larger enterprise?

Eg. Pilots walk out and are tarred as being self-serving. Or, pilots walk out in co-ordination with plane staff and ground crew?

But more importantly, can we assume the Gilded Age (GA) ver.1.0 and industrial workers pushing for economic benefits resembles GA 2.0 and service workers? The necessary thread must be a sense of solidarity. GA1.0 demonstrated the effectiveness of commonality. How much evidence of commonality w/GA2.0? Some has occurred with precarious workers across healthcare (home care workers), food (franchise workers/fast food), hotel staff (housekeeping and janitorial) and retail (chainstore/Walmart) subsections of the service sector.

How to build on that? Can the various unions involved w/these movements/”strikes” (really minority walkouts) unite into one alliance? Could a bottom up effort work? What about platform workers?

Is it possible to revive the old union hiring hall concept to be revised to include all the subsections of this sector? Work Centers function in several places and maybe could be tweaked to include a wider range of work assignments

If labour markets are going ‘back to the future’, the study of historical labour market institutions can provide useful lessons for the modern world.

The American Gilded Age labour market came extraordinarily close to the archetypical labour market taught in Economics 101 (Fishback 1998).

The first sentence makes total sense and the second sentence makes absolutely no sense and contradicts the claimed intent in the first sentence. No monopolistic or oligopolistic corporations? No resort to the power of the state to enforce yellow dog contracts? Workers paid their marginal product? Competitive product and labor markets? What?

This is what happens when one tries to play the economists’ game on their own terms. I have no doubt that any reasonably “competent” neoclassical economist could come up with a host of reasons why the data referenced by the authors actually reinforces “the archetypal labor market taught in Economics 101, except for some specific, exceptional circumstances that we can, thankfully, safely ignore going forward. And tax cuts.

If labour markets are going ‘back to the future’, the study of historical labour market institutions can provide useful lessons for the modern world.

The American Gilded Age labour market came extraordinarily close to the archetypical labour market taught in Economics 101 (Fishback 1998).

Left in Wisconsin, you are so right.

I just wish these academics would at least once jump out of their ivory towers and look around at the rest of the world instead of narrowly focusing on the USA. Please professors, take a look at what has worked as far as capital and labor is concerned in the rest of the world.

Case in point, Denmark!

Now, I know these profs are already rending their gowns and clutching their pearls and looking for the fainting couch screaming Socialism, Socialism all the way. Maybe this country could use a bit of Socialism.

Denmark, as I recall, had horrendous labor strife in the late 1800’s and decided to do something about it. They passed laws in the 1880’s or ’90’s to solve the problem. One of the laws they passed that most impressed me – It is unlawful in Denmark for a company to try to break a strike. Conversely, it is unlawful for workers to resort to wildcat strikes, work stoppages,etc. outside of their contracts. Imagine if this law was in effect at the turn of the century. Figure 2 & 3 of the author’s article would have to be radically revised, especially with regards to the over 600 deaths on the picket lines!

Another thing Denmark created was a Labor Court. All disputes between workers and management are adjudicated in a special Labor Court.

Maybe, that contributes to Denmark having a minimum wage of about $17/hr and being voted the happiest people in the world many times over.