Yves here. It should come as no surprise that, with the most fabulously overpriced health care system in the world, it delivers notably poor outcomes in terms of measurable results, such as life expectancy. This post seeks to get a better understanding as to why. Note that the analysis omits certain issues, for instance, that there is solid evidence that suggests that more unequal societies are more unhealthy. But that would mean US results should be compared to the subset of pretty to very unequal counties, and you’d still find the same result, that high US expenditures do not translate into better results.

This short study identifies that spending on healthcare is very unequal, and intuitively seems not explainable by differences in the health of the population (and Medicaid data suggests that this intuition has merit).

So the question for reader is: what might explain this pattern? One issue, which is not discussed as often in the press as it needs to be, is that the driver of the high cost of end of life care often amounts to what Lambert calls, “Insert tube, extract rents” of sheer looting. The press will occasionally feature stories about how an aged parent goes into a hospital or other institutional setting, and despite the relatives having a medical power of attorney plus clear, legally well documented instructions that the patient does not want high cost interventions with limited life extension potential, that the medical professionals come close to or actually do threaten the family with litigation if they attempt to remove the patient or restrict care.

Another issue for patients is the way that they’ve been conditioned to believe that Something Can Be Done when they have a condition that is pretty much a permanent impairment. This is particularly common with orthopedic procedures. I see individuals in my gym that I can tell from how they discuss their surgeries that they’ve been overtreated for no or negative benefit.

Other thoughts?

By Max Rosner, Research Fellow, INET, Oxford. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

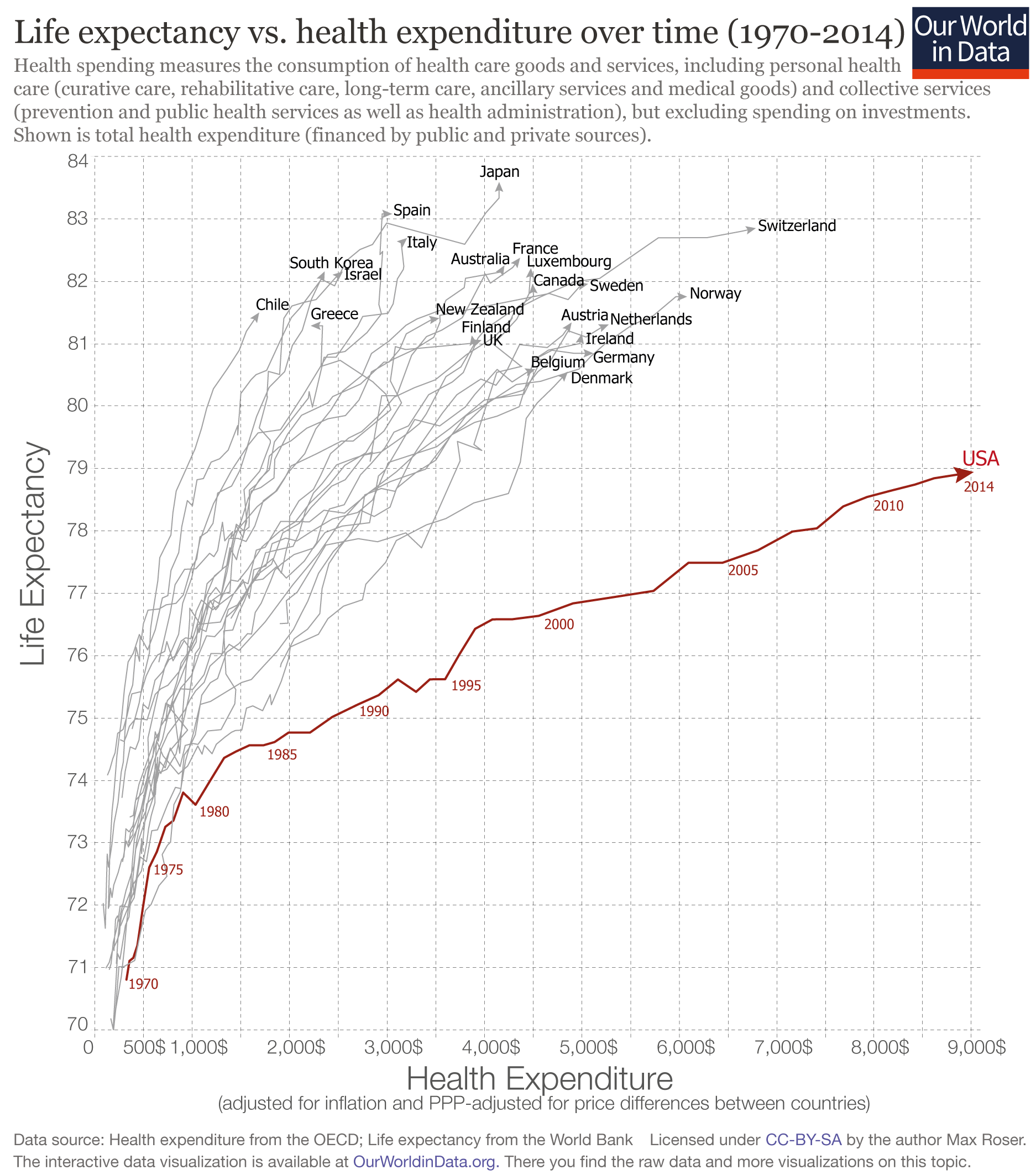

The US stands out as an outlier: the US spends far more on health than any other country, yet the life expectancy of the American population is not longer but actually shorter than in other countries that spend far less..

The graph shows the relationship between what a country spends on health per person and life expectancy in that country between 1970 and 2014 for a number of rich countries.

If we look at the time trend for each country we first notice that all countries have followed an upward trajectory – the population lives increasingly longer as health expenditure increased. But again the US stands out as the the country is following a much flatter trajectory; gains in life expectancy from additional health spending in the U.S. were much smaller than in the other high-income countries, particularly since the mid-1980s.

This development led to a large inequality between the US and other rich countries: In the US health spending per capita is often more than three-times higher than in other rich countries, yet the populations of countries with much lower health spending than the US enjoy considerably longer lives. In the most extreme case we see that Americans spend 5-times more than Chileans, but the population of Chile actually lives longer than Americans. The table at the end of this post shows the latest data for all countries so that you can study the data directly.

Life Expectancy vs. Health Expenditure Over Time, 1970-2014 1

There are several aspects that contribute to the US being such an extreme outlier: Studies find that administrative costs in the health sector are higher in the US than in other countries; The price comparisons between countries rely on adjustment which are not ideally suited for comparisons of health costs and this might make comparisons more difficult. Sometimes it is also pointed out in these comparisons that violence rates in the US are higher than in other rich countries (and this is true). But while this could explain the difference in levels, it is not a likely explanation for the difference in trends. Over the period shown in the chart above violence and homicides have fallen in the US more than in other rich countries and this should have led to a narrowing of the difference to other countries and not to the increase that we see.

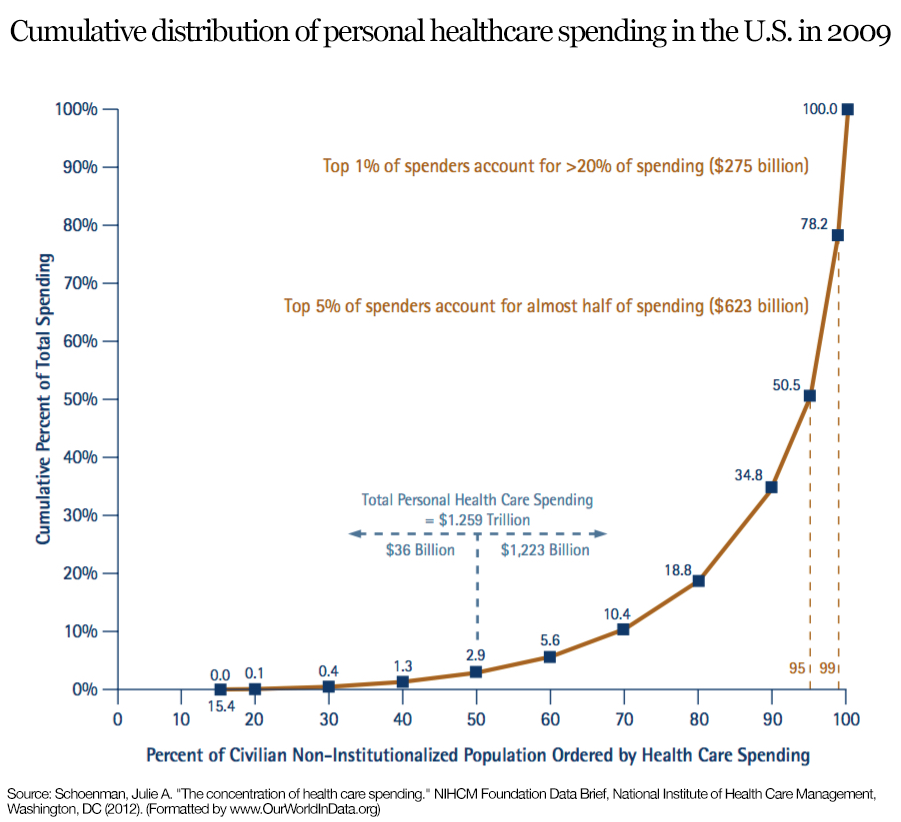

One of the reasons for the underachievement of the US is the large inequality in health spending. The chart above showed that average per capita spending on health is exceptionally high, but the average does not tell you about how much each individual in the US receives. The US healthcare system is characterized by little access to care for some and very high expenditure on health by others.

The following graph shows this inequality. The top 5% of spenders accounts for almost half of all health care spending in the US.

This chart is produced by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM) and it shows the cumulative distribution of healthcare spending per person in the U.S., using data on personal expenditures during the year 2009. The source of the data is the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – a nationally representative longitudinal survey that collects information on healthcare utilization and expenditure, health insurance, and health status, as well sociodemographic and economic characteristics for civilian non-institutionalized population. According to the source, the data refers to ‘non-institutionalized civilian population’, in the sense that it excludes care provided to residents of institutions, such as long-term care facilities and penitentiaries, as well as care for military and other non-civilian members of the population. The data corresponds to ‘personal healthcare services’, in the sense that they exclude administrative costs, research, capital investments and many other public and private programs such as school health and worksite wellness.

This graph should be read similarly to a Lorenz curve: the fact that the cumulative distribution of spending bends sharply away from the 45% degree line is a measure of high inequality (this is the intuition of the Gini coefficient that we discuss in our income inequality data entry). As it can be seen, the top 5% of spenders account for almost half of spending, and the top 1% account for more than 20%. Some concentration in expenditure is certainly to be expected when looking at the distribution across the entire population – because it is in the nature of healthcare that some individuals, particularly those older and with complicated health conditions, will require large expenditure –, these figures seem remarkably large and suggest important inequality in access. Indeed, the publisher of the graph notes that a report from the Medicare Payment Assessment Commission shows that personal spending for individuals covered by Medicaid is less concentrated than for the population as a whole.

Cumulative Distribution of Personal Healthcare Spending in the U.S., 2009 – NIHCM (2012) 2

Latest available data on life expectancy and spending on health per capita in OECD countries.

| Country | Life exectancy | Health Spending per capita |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 78.94 | 9,024.21 $ |

| Switzerland | 82.85 | 6,786.57 $ |

| Norway | 81.75 | 6,081.00 $ |

| Netherlands | 81.30 | 5,276.60 $ |

| Germany | 80.84 | 5,119.21 $ |

| Sweden | 81.96 | 5,065.16 $ |

| Ireland | 81.15 | 5,001.32 $ |

| Austria | 81.34 | 4,896.00 $ |

| Denmark | 80.55 | 4,857.03 $ |

| Belgium | 80.59 | 4,522.04 $ |

| Canada | 81.96 | 4,495.69 $ |

| Luxembourg | 82.21 | 4,478.97 $ |

| France | 82.37 | 4,366.99 $ |

| Australia | 82.25 | 4,206.85 $ |

| Japan | 83.59 | 4,152.37 $ |

| United Kingdom | 81.06 | 3,971.39 $ |

| Iceland | 82.06 | 3,896.93 $ |

| Finland | 81.13 | 3,871.39 $ |

| New Zealand | 81.40 | 3,537.26 $ |

| Italy | 82.69 | 3,206.83 $ |

| Spain | 83.08 | 3,053.07 $ |

| Slovenia | 80.52 | 2,598.91 $ |

| Portugal | 80.72 | 2,583.84 $ |

| Israel | 82.15 | 2,547.40 $ |

| Czech Republic | 78.28 | 2,386.34 $ |

| South Korea | 82.16 | 2,361.44 $ |

| Greece | 81.29 | 2,220.11 $ |

| Slovakia | 76.71 | 1,970.52 $ |

| Hungary | 75.87 | 1,796.60 $ |

| Estonia | 77.24 | 1,724.51 $ |

| Lithuania | 73.97 | 1,720.84 $ |

| Chile | 81.50 | 1,688.52 $ |

| Poland | 77.25 | 1,624.87 $ |

| Costa Rica | 79.40 | 1,393.95 $ |

| Russia | 70.37 | 1,368.75 $ |

| Latvia | 74.19 | 1,295.01 $ |

| South Africa | 57.18 | 1,146.47 $ |

| Mexico | 76.72 | 1,052.66 $ |

| Turkey | 75.16 | 990.19 $ |

| Colombia | 73.99 | 964.50 $ |

| China | 75.78 | 730.52 $ |

| Indonesia | 68.89 | 302.12 $ |

| India | 68.01 | 267.41 $ |

Footnotes

- Graph produced by Max Roser on 25 July 2016 using OECD data on health spending and World Bank data on life expectancy at birth.The definition of health spending given by the OECD is the following: “Health spending measures the final consumption of health care goods and services (i.e. current health expenditure) including personal health care (curative care, rehabilitative care, long-term care, ancillary services and medical goods) and collective services (prevention and public health services as well as health administration), but excluding spending on investments. Health care is financed through a mix of financing arrangements including government spending and compulsory health insurance (“public”) as well as voluntary health insurance and private funds such as households’ out-of-pocket payments, NGOs and private corporations (“private”). This indicator is presented as a total and by type of financing (“public”, “private”, “out-of-pocket”) and is measured as a share of GDP, as a share of total health spending and in USD per capita (using economy-wide PPPs).”

- Figure published in Schoenman, Julie A. “The concentration of health care spending.” NIHCM Foundation Data Brief, National Institute of Health Care Management, Washington, DC (2012). Original source data comes from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey – a nationally representative longitudinal survey that collects information on healthcare utilization and expenditure, health insurance, and health status, as well sociodemographic and economic characteristics for civilian non-institutionalized population. According to the source, the data refers to ‘non-institutionalized civilian population’, in the sense that it excludes care provided to residents of institutions, such as long-term care facilities and penitentiaries, as well as care for military and other non-civilian members of the population. The data corresponds to ‘personal healthcare services’, in the sense that they exclude administrative costs, research, capital investments and many other public and private programs such as school health and worksite wellness.

Treating “symptoms” – for profit – of environmentally induced or more complicated issues is not Hippocratic anything… its an enrichment process.

Why is the US an outlier? Money knowledge and power.

Profit-driven delivery system.

Market dynamics of hospitals and other health facilities

Unequal power dynamic between the medical-industrial complex and consumers & communities

Major cognitive biases and errors:

Healthcare is the main path to health

Disease is deviation from norms of biological variables

New is better and more is better

More expensive is better

Earlier is better

To know is better than not to know

Certainty is possible

Technology is intrinsically good

Medical care is an intrinsic good rather than just a means

Excessive individualism

The hegemony of a reductionist view of science

BTW, notice the turn in trajectory occurs in 1980. Amazing what a vast ensemble of features of US society all shifted around that time. In that sense, the medical industrial complex participated in the general solution to the crisis of the 1970’s: debt fueled consumption, rising inequality, and the long march of neoliberalism through all our institutions. In the process the MIC became a giant wealth extraction machine. Huge amounts — maybe 40% — of what we do in medicine is ritualistic and has little impact on health.

Racism.

Vikas and Torsten: Excellent synthesis.

One of the interesting observations is that two of the countries with excellent diets, Japan and Italy, are up top. So as a counterexample, I will throw in the Heart-Attack Belt, from Virginia to Texas, which is known for its diet-related health problems.

Remarkable, too, is the Greek data point: In spite of economic devastation, the Greeks have kept themselves healthy. All that olive oil.

Clearly lifestyle has a role, although it should be noted that in Japan and Greece everyone seems to smoke, so its more than just a good diet.

Of course, much of northern Europe, from Germany to the UK and Ireland shares a love with USasians with fatty over-processed food, and in some of those countries rates of smoking and drinking are significantly higher than in the US.

Genes long selected for tobacco tolerance.

Switch from HMOs to PPOs made for better profits and lousier health care. My kids born from 1989 to 1998, throw in my own emergency appendectomy in 1992 and I’ve lived through this.

Honestly, the collapse of ACA/Obamacare can’t come fast enough. Single payer like Canada or France seems simplest; insurance companies and other profiteers can go pound sand. Basic health and wellness cannot be a profit center, period.

I thought tobacco was a North American invention.

I’ve heard it said that in Asia, smoking is still largely a male-dominated pastime (perhaps that is changing now). European and North American women have been smoking in large numbers far longer.

Lifestyle does not have a role, it is crucial!!!

I have recently visited the US with my family of four and one of my main concerns was health insurance during our trip. Something i don’t bother to think about when I visit France, Italy, the UK…Part of the lifestyle is the health system. Universal public insurance makes you feel safer. The best way to feel this safety in the US is to be very rich. This makes the need to be wealthy more obsessive and that, by itself, is not a healthy part of the lifestyle. Excessive medication and treatments are a byproduct of the system.

I was astonished one day we visited Las Vegas (not to gamble, Las Vegas is a curiosity and on the way to several beautiful places) and because we did not gamble we went early to our rooms and I turned on the TV. To my surprise the first channel that came to my view was issuing the excellent J&E Coen’s Fargo, and I decided to watch the film. I couldn’t believe that many of the advertisements dealed with a company offering legal advice for patients of certain diseases that had undergone treatments deemed harmful.

Agree with above IOne big problem: Incentives in a for profit system. There is bigger money in procedures and inpatient care. This may get worse over time if you recall that managed care doesn’t like paying for outpatient services. Especially now with high deductible plans where outpatient services are not covered at all for most people since you have to burn through a 10 or 12 k deductibles.Also hospitals have accumulated an impressive number of middle managers. All of these people are expected to come up with creative ways to create profit. According to BLS their numbers are expected to increase:

http://www.bls.gov/ooh/management/medical-and-health-services-managers.htm

The Center for Medicare Service (CMS) just changed the rule on deductibles for 2016: on all plans across the U.S. the maximum per person is $6,600 and one person in a multiple person household can satisfy their deductible and be done with it. On all deductible plans, the deductible applies to all facility based services equally, not just some services.

Here’s a quick look at some of the OECD Health data, made a pinboard:

https://data.oecd.org/pinboard/4i1v

comparing 1970-2015 Health spending with similar period Doctors’ consultations (per capita), Hospital discharge rates (per per 100,000 inhabitants, general indicator of hospital usage one day or longer) and Pharmaceutical spending (percentage of total, not in hospital), to see if any of these could account for the high spending, looks like a “no”. US pharmaceuticals are 12.32 in 2015 and never higher than 13.18 (2006), and lower than most listed nations, that leaves about 87% going towards non-pharm services, I suspect that “administrative” costs are easily 50% of that. Nice data set and UI, but I couldn’t identify health care admin costs anywhere.

Click the chart titles to zoom in and get descriptions.

Ugh, here’s the right link for the charts: https://data.oecd.org/pinboard/4i1z

Interestingly, pharmaceutical spending does not correlate with life expentancy increases in any of those countries analysed

Cost, or even quality, of health care may not be the factors at play in the life expectancy discrepancies between the US and everybody else.

Deregulation and lax enforcement give us toxic work and home environments, less healthy food and water, not to mention stressors/hazards from a poor economy and decaying infrastructure… health care alone can’t compensate for all of it. Even when it costs twice as much! How counter-intuitive is that?

:(

Oh, well. Just another failure-right behind broadening income inequality, ineffectual action on climate change, and never-ending war–of the Obama administration. More people having health insurance=more people locked up and paying into the most broken healthcare system in the Western world.

rent seeking.

The assumption that health spending should drive longevity needs to be re-examined. Certainly, spending on public health measure like clean water, uncontaminated food, and effective infection control measures can have an impact. But spending on erectile dysfunction and cosmetic surgery is not contributing to longevity. Nor is out sized spending on cancer therapies that offer at best a few more months of survival. Finally, lifestyle behaviors such as overeating, bad diets, smoking, lack of exercise while drive health care spending that would otherwise not be needed.

Good observation, but the point of the first chart is that life expectancy is longer in OECD countries that spend much less per capita. The point of this isn’t that the US needs to spend more, the point is that it spends way more than other countries and gets way less in terms of life expectancy of our population.

We have an overly litigious society which is the root of it. Our doctors have to go to school longer and train longer then most other countries, same with our nurses. But the major driver is fear of being sued for malpractice. Doctors run tons and tons of unnecessary tests to rule out things they don’t think are likely. They assume the insurance covers it and often don’t know the cost of the test in the first place.

The rent seeking isn’t always as intentional here IMO.

This is a great graph. My view as a long time physician is that the answer is simple but politically impossible. Three groups are going to have to give something up……care providers, patients and lawyers. The doctors need to all be on government salary. There can be no incentive for production. That will allow doctors to provide the care they think will work and ignore the care that they realize will not work. On salary a doctor is not going to do worker`s compensation spine fusions. There is a lot of pressure by patients for care that they think they want but the big driver is that in our poor economy patients need objectification and documentation of their disability for VA or Social Security or Worker`s comp or personal injury. A back strain with no surgery might be worth 30,000 but with a spine fusion it could be 500,000 and attorneys and the patients are well aware of this. A soldier that is a poor performer who is going to be discharged from the service is eager to get a spine fusion that will guarantee his pay for life. Likewise a worker`s comp patient is happy to get a spine fusion in return for a lifetime sinecure and retirement in his native country as a wealthy man. For those that cannot or will not work we need some sort of safety net that is designed to take the medical evidence out of SSI. In our economy the judges are liberal, and the attorneys get the retroactive SS benefits as their fee. The VA system is similar. A rule of thumb is that a personal injury settlement is going to be four times the medical costs. That means attorney fees are determined by medical costs. A huge amount of medical care is provided to support financial claims adjudicated by attorneys. The last thing is that patients have to give up the notion of patient satisfaction. The doctors went to med school and were selected in one way or another for altruism, intellect, etc. They should be the ones deciding what sort of care should be done with no financial or other incentive one way or another. If it is a condition that cannot be cured so be it. If they want chronic narcotics the doctor has no incentive to prescribe unless he/she is convinced it will work. England is a lot like that but not the US. If patients do not like it they can, at their own expense, go elsewhere in the world or pay for their own care. To a degree this was the system we had in the US before Medicare. Patients that could not pay got ward care. Now that the government is funding most of it One way or another we cannot go back. One reason India is so low in terms of costs is that they have a national system that takes care of essentials with doctors on salary. The waits are horrendous and the outcomes can be problematic often. On the other hand it is free. If it is elective the patients have to go to a private doctor often government doctors working on the side and either pay for it there or immigrate to the US or Germany for asylum or whatever so other taxpayers can fund their care. They key point is that based on my experience basic necessary care is available in India and elective care is just elective and the patients have to figure it out. I see many Indian patients here in the US who have immigrated and now consume vast amounts of elective medical care that really does not improve their situation. If the US could get a handle of medical costs it would be like giving everyone in the US a huge pay raise and the benefits to the economy would be huge. The only losers would be the doctors who are in medicine to milk the system (not all are but Gresham`s Law does apply), the lawyers, the hospital administrator industry, and the drug companies (if the doctor is on salary and there is no patient satisfaction score and there is no controlled scientific evidence of the superior effect of a medication all the me too medicines advertised on CNN would not get prescribed unless. the patient paid for it and prices would drop. Many of these medicines cost 50,000 per year and up.). Now we treat drug addicts and others for Hepatitis C at great expense and they just reinfect. Without patient satisfaction the doctors can decide whether they are going to do it over and over. We see this in the prison population especially. The Hep C treatment costs are over the top with no long term benefit. Without a salary model nothing will work. Free enterprise mixed with government payment for care mixed with our legal system is a disaster and I wonder how high our costs will go before something radical has to be done. We are at 20% of the economy now, conservatively, would it be when we reach 50% of the economy devoted to “health care.”

Hey Felix. Hit the enter key twice every once in awhile, maybe just randomly while you are typing. I would Love to read what you have to say but could you edit it into paragraphs and repost? What you’ve posted is unreadable.

I also started to read it with interest and then stopped because I simply couldn’t read it as posted.

I thought Felix’s comment was amazing, dense with extremely valuable insight and information.

Presumably, Felix has spent years of his life on microbiology, anatomy, and related topics. Why be insulting because he didn’t manage to take a course in grammar or paragraph structure during med school?

I took some of my valuable time to read his comment, and I was well compensated for my effort.

Regards, rOTL

It’s a great comment. It’s also… just a little grey. I imagine on a small screen that would be hard to read. And a reader who skipped it for that reason would miss Felix’s insights.

So far as I am aware, the comment is entirely incorrect about India – few doctors are on public salaries. Modi has proposed a basic national healthcare system but – inevitably – has not delivered so far.

That is correct and they work in government hospitals and there are not many of them so they are really busy and they only take care of things that really need a doctor badly. The elective things are done privately or not done at all and I apologize about my comment because it is being dictated on a cell Phone because I have no Internet here. Since the private Market is Limited many come to the First world And they expect a first-world income. India, the Phillipines, Sri Lanka, Iraq in the past and maybe now produce doctors beyond what they can support and the excess production which is very substantial is expected to go abroad and work in Europe and the United States whether they are needed or not as it is a financial thing and not a health care issue. And contrary to what you think that more doctors mean lower costs more doctors mean more costs because the cost of a doctor is not so much in what the doctor earns but the cost is in the tests, surgeries and treatments that a doctor orders or performs. That means that we would all be better off if our doctors were on salary no matter how little they work. We consider fireman to be Public Safety officers and I don’t see anyone complaining if they sit around the fire house and play basketball and I don’t see anyone burning buildings down to make them more productive. Having doctors around should be considered an insurance policy. I always thought that one of the reasons that doctors played golf on Wednesday afternoon in the sixties and fifties was that with 90% top tax rates it really didn’t make sense to do one more surgery or see 10 more patients and I have seen a difference as the tax rate has gone down. But readers should not think that the legal industry isn’t eating a huge chunk of medical money because what would personal injury attorneys do if we controlled medical costs.

US infant mortality rates are high. US death rate from “medical error” also high. These factors are a big part of why US life expectancy is

relatively lower than that of other developed countries.

Wealth discrepancies also affect outcome and life expectancy in the US. If you’re wealthy, not only do you live longer than other Americans, your life expectancy is on an upward curve while that of less wealthy Americans has been on decline for some time. The average may be relatively stable, though the discrepancies based on wealth continue to diverge.

Overall cost of medical care — when it can be accessed at all — continues to increase quite regardless of outcome and life expectancy because, IMNSHO, successful outcomes and increasing life expectancy are not necessarily goals of the industry. Primary goal is extraction of money.

Remove the money extraction incentives and things change.

In the US, infant mortality is measured from time of birth.

In some other nations, it is measured at 48 hours — IOW, if the baby is still alive after 48 hours, then it is counted.

This was true in the 1980s, and IIRC, it remains true today.

US infant mortality rates are high compared to almost any other developed nation. Are you saying that at 48 hrs after birth they are comparable to other developed nations?

As is true of so much of US medical care, it depends a great deal on ability to pay and class/social status.

Felix’s statement is useful for cost analysis, not so much with regard to lower overall life expectancy for US population.

Felix

Doctors on salary– you describe the Mayo Clinic.

Btw, ive been using the iphone text reader–is that cheating?

I’ll point out explicitly that tbe MDs, and other professionals at Mayo are on salary, and not as Government employees.

The notion that the alternative model to “for profit” MD remuneration is being Governmrnt employees is a false alternative.

Mayo C is ranked as the #1 medical instituition in the US*, so why would we want to use it’s not for profit medical service delivery model?

That said, the rest of your comments,from your professional observations sound quite reasonable.

*US News & World Report current ranking

Well, seems to me that someone somewhere has a done a study of where healthcare dollars go in the US. I am thinking that information would be helpful in this regard.

https://www.rethinkreform.com/rethink-where-do-your-healthcare-dollars-go/

I don’t know who funds this particular outfit (they seem a bit too friendly to insurance companies to be a neutral player). But, I suspect the graphic on healthcare spending is about right. It suggests that hospitals and doctors suck up about two-thirds of healthcare dollars spent. Juding from the palatial opalescence of our local (Catholic) hospital, I have no doubt it is true. As a personal anecdote, my wife had a outpatient surgery there about a year ago, the charge to my insurer, seperate from the surgeon’s bill, $21,000 for three hours in the hospital, including pre-op, surgery, and post-op. Were we presented with this total cost before deciding to have the surgery there? No, we were just told that our insurer would pay more of the surgery bill there.

I conclude from this post that whatever we’re buying with our Health Care dollars — it isn’t health care.

Similarly whatever we’re buying with our Defense dollars — it isn’t defense.

http://www.ncpa.org/pub/ba596…I think length of life is the wrong measure. I believe that outcome once diagnosed is a better measure of medical quality.

Good point. My guess is those who can afford the best health care live longer and have better outcomes. Good luck to the rest of us.

I would like your comment to go to the top of the heap because I have been harping on this very topic for lo these past eight years. Quality of care is really the issue, not how much we spend. If we focused on quality of care, costs would follow along in a downward trend. Other countries have vastly similar quality of care issues (the number one being a crowding out of care by overuse and unneeded care)but it seems the culprit here is that we have private carriers who add too much cost burden.

So, just moving to a universal carrier would not solve the cost issue, that would remain. And costs are still an issue even if subsidized by the government. I’m all for a universal carrier like Medicare, I just want to see the quality of care issue kept in front of us. Lousy care is still lousy even if the government subsidizes it.

Length of life isn’t wrong – it’s just too ballparky. The cumulative distribution chart is the humdinger here. 5% of the population accounts for almost half of personal healthcare spending in the US! Haven’t seen that one before – many thanks Yves!

“Our goal is to promote private, free-market…” etc. I find these stats highly suspect.

Anecdotally, there is an enormous misallocation of resources in the US system, even for people who do get treated. As just one example, over testing for cancers and cardiac problems leads to over treatment and over medication of phantom illnesses. Most European medical systems test for very few cancers because in only a handful of cases (cervical and breast for under 40 year old women) are there demonstrated benefits. Likewise, heart problems are not tested for unless a patient shows symptoms. And as Yves suggests there seems anecdotally to be an over emphasis on surgical interventions for a range of conditions that could be treated better with anti-inflammatories, a better diet, and appropriate exercise.

One thing I can’t explain is why in such a competitive system, there aren’t more drivers to force down the costs of many interventions. One result of various EU Directives and free movement within Europe was the the cost of some elective medical interventions – such as dental work or laser eye treatment – dropped significantly as people simply chose to travel to countries where they were cheaper. Yet this doesn’t seem to happen in the US. This strongly suggests anti-competitive behaviour, but I’d be interested to know how its engineered.

I’ll give this a shot, I think this is the basic scenario, if not, someone please correct it.

The effectively non/anti-competitive environment in the US is produced by the pricing of procedures and level of covered care being set by the insurance companies (aka carriers), their control over access to the care providers.

Patients are limited to getting care from providers within the carriers’ “payment networks”. They have to pay full costs for out-of-network treatments/services, and those costs don’t count to their deductibles (a level of payment before insurance coverage that the insured pays, cheaper plans have higher deductibles). Some plans require co-payments (partial payment) for all or most treatments. Plans and pricing vary from state to state.

As more people are signed up to (effectively mandatory) insurance plans, providers (doctors/dentists/services) are forced to sign up with carriers in order to have access to their pools of patients.

By joining (subscribing to) an insurer’s payment network, a provider is (mostly) assured that they will receive timely payment. But the insurer now determines what the care provider will be paid for a given procedure. This pricing is usually low, benefiting the carrier’s profits, so the care provider gets little revenue or incentive to deliver more than minimal/fixed level service to the patient.

Insurers also limit the diagnostics/treatments/services/meds that they cover, anybody that doesn’t fit into that template pays out of pocket or doesn’t get the care. When the care providers bill the patients directly, they may increase pricing, to cover collection costs, and just because (this used to be less common but seems to be increasing).

Any charges for treatments/services that are not covered by the carrier (or in excess of their pricing) must be borne by the patient (possibly including interest and collection charges), and is NOT counted against the patient’s deductible (if any). Similarly, care/services the patient gets from care providers that are not in their insurer’s network don’t count against their deductible.

So basically, insurers lower the level of health care to their clients, and limit available treatments, diagnostics, services, etc. Service competition in the health care market is suppressed through fixed pricing, and comprehensiveness of care is driven down. If you want better care, you buy it, on top of insurance costs, and apart from deductibles. This is for-profit health care in a captured and controlled market.

Thanks dk, that makes some sense, although I still can’t see why it doesn’t seem to be in the interests of insurers to work harder to drive down the cost of high end treatments. There seems to be a gross disparity between the cost of some high end treatments in the US to other developed countries. And I’ve often wondered about the reluctance of US insurers to pursue medical care in other countries (or low cost States) – in Asia its very common for people to travel across borders (usually to Thailand, Malaysia, India or Singapore) in search of cheaper, better hospital care. This is often encouraged by governments and private insurers.

To give one example, I know an Irish American family from New Jersey who maintained an Irish residential property, so were able to make use of both health care systems (they were quite well off, so had good insurance) when needed. When one member family member was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, they searched for an appropriate private nursing home/treatment centre. Even stripping out the subvention the Irish government offered (far more generous than any aid in the US), the Irish centres they looked at were less than half the annual price of an equivalent nursing home in NJ. Ireland has quite high property prices, and the minimum wage is around $10 an hour or more, so I don’t see how such a huge price differential could be justified by base property/staff costs. I can only assume there are major drivers forcing up prices which can only be what Yves would rightly describe as looting practices.

I woould frame your question differently: would be profitable a health insurer offering the same coverage for lower premium?

No offence, but why would you frame it that way? Asking that question presumes a lot, and could obscure valuable insights on the actual mechanisms.

The determination of “profitable” is relative to the class of the health insurer (and other members of the payment sink). One can make the argument that it’s profitable, in terms of aggregated social benefits, to provide health services at a financial loss.

The inflations for final costs vary between industries, but in this case, it may be the insurance costs of the nursing homes being passed on to the consumers. Also, homes pad all of their operating costs, like buying supplies and meds in bulk w/discounts, but charging at unit prices. And staff are often contracted through agencies, which take a hefty cut and pay the workers as little as possible.

High population + collapsed economy – (regulation + oversight) = many middlepersons, as well as a markets dominated by large regional/national conglomerates, increasingly funded by private equity. High business insurance rates and local pricing pressures drive out smaller independent businesses.

Homeopathy is cheaper and far more effective for the vast majority of problems.

well, it’s cheaper all right . . .

I think our health-care spending and stalled life-span reflect bigger problems with our society that grow out of our belief in and money and stuff accumulation over everything else. Yes our profit-driven health industry drives costs up. But what about our excessive work hours and lack of a safety net as well as weak family and community ties? Bad diets exist at the poverty level mostly because fast food and processed junk is cheaper than good food and can be grabbed on the way home from the second job. How many high earners drink too much to deal with the stress of trying to stay on the top of the heap? And how many under-employed in the middle veg away in front of the tv with a bag of chips every night because they have lost hope? Rather than helping us to thrive, it’s pretty clear that the American way of life we have created is doing the opposite. Guess we are just exceptional.

Good analysis and the social cost of not having a social network for people to rely on is stupendous in so many ways. Poor and low income households (40% ? of the U. S?) pay more for health care-usually because health care is not available for a host of reasons. One being that the providers are out of reach geographically.

anyone reading these comments would do well to consider the link here before going any further on the question of why health care costs so much in this country-it’s because we have so many poor people.

There are a number of reasons health care is so expensive in this country.

1. We do not have universal health care as most of the other countries in the Life Expectancy vs. Health Expenditure Over Time, 1970-2014 graph. Because we are now at the peak of several decades of non care for millions, catastrophic care enters into the picture at a late point in millions of people’s lives. Unfortunately many don’t even make it to the catastrophe that they live through, they merely die at an early age. The lack of care throughout the lifespan of millions certainly has to be factored into the picture.

2. U.S. workers have worse working conditions than the countries we are compared to in the above graph.

3. Many practitioner’s fees are higher (often the highest) than those in the comparable countries This is leveraging the overuse of specialists by a worried society that is willing to have their insurance plan pay for too many services in the name of assauging a frantic, angry family that threatens with litigation at every sign of suffering by the beloved family member. Whether a single payer foots the bill or many private carriers pay the claim, there’s a reason the word cost has any meaning-we ration care no matter the philosophical or economic or financial reason. Any major city can only staff so many ER’s, only so many people can work in the medical field. Facing facts on medical care forces most people in this country to go ballistic at some point. Which leads immediately to my next point.

4. When services and goods for medical care are already in short supply, over demand can probably be cited as a key factor in driving up costs. This factor has to be out of proportion to what is going on-take a service that is in short supply and lean on it.

5. I’ve harped on this here before so I’ll just say this: Quality of care, because of the factors already discussed, is lower in the U. S. than in the countries in our focus. But add to that the immediate problem, faced by those countries as well, that we have no way of knowing who the quality providers are and we’re all thrown into the hopper. We know more about the abilities of million dollar a year basketball players than we do equally high priced surgeons and diagnosticians.

6. Almost forgot: We nuked ourselves and with the exception of Japan ( them: 2 bombs, us: about a thousand) no other country has that in their background. The downwind area from Nevada could be almost the whole continent .

http://www.commondreams.org/views01/0105-06.htm

Quality of care is a topic no one wants to discuss and has its own dynamics that really affect cost. One re-entry back to the surgical facility for a botched procedure is literally priceless and can also result in death.

“Health”. How do we define that word?

I’d define it rather differently than many here (despite–or due to–having professional healthcare qualifications and experience).

There are many systemic financial interests that have manipulated and distorted our consensus understanding and expectations of “health” and “healthcare” and “healing”.

Cultural psychospiritual manipulations and distortions also impact our understandings of health, disease and healing.

One can find other ways if one is not satisfied with the explanations, procedures and results of the consensus medical system.

Another commenter mentioned homeopathy. Other alternative practices can also be appropriate. Nutritional/dietary changes are helpful for some people. Other approaches are less widely known (e.g., Buteyko method; or Perelandra’s Medical Assistance Program or Microbial Balancing Program, or people such as this). Wise doctors can play valuable roles.

One thing’s certain–healthcare approaches are not a one-size-fits-all thing. I prefer to use some options and not others. There is no one right way, even for “conditions” that might at first glance be identical or similar. Quality healthcare respect our uniqueness.

Life expectancy data is not always accurate. Remember this scandal?

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/sep/10/japenese-centenarians-records

“More than 230,000 Japanese people listed as 100 years old cannot be located and many may have died decades ago, according to a government survey released today.

The justice ministry said the survey found that more than 77,000 people listed as still alive in local government records would have to be aged at least 120, and 884 would be 150 or older.

The figures have exposed antiquated methods of record-keeping and fuelled fears that some families are deliberately hiding the deaths of elderly relatives in order to claim their pensions.

The nationwide survey was launched in August after police discovered the mummified corpse of Sogen Kato, who at 111 was listed as Tokyo’s oldest man, in his family home 32 years after his death.

Kato’s granddaughter has been arrested on suspicion of abandoning his body and receiving millions of yen in pension payments after his unreported death.”

Also it’s cheap to take care of elderly people if you just let them die in a heat wave; remember 2003 (14,000 just in France)(https://www.britannica.com/event/European-heat-wave-of-2003). That made the 739 (mostly old people) dead in Chicago in 1995 look like peanuts (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1995_Chicago_heat_wave).

Average life expectancy is actually amazingly high in the U.S., when you consider how many impoverished, badly housed, badly fed, badly educated, drug addicted and repeatedly incarcerated people we have. I have read it claimed that the life expectancy of Swedish Americans is much higher than that of Swedes; 81.96 for Swedes (per the chart above) is not all that impressive given the utopia they are said to live in (I can’t seem to find real data re Swedish Americans). I wonder what the average life expectancy in the U.S. would be if young black men weren’t dying in droves due to being shot, and young white people now dying in droves due to drug addiction; probably quite impressive; enough to make our expenditures look worth it all.

At age 55, I had been a runner for 20 years, ran 5 miles a day, went to the gym 5 days a week, had 10% body fat, ate a fairly clean diet and took no medications.

I began to experience severe pain down my leg.. I tried every non medical treatment I could think of before going to a medical doctor..

8 years later, I am still in pain and I’m convinced that on the timeline of medical knowledge we are currently just marginally better than the Barbers of the middle ages who used leaches and bloodletting to heal the sick. I say this having been to some of the BEST hospitals in NYC, Philly and even had my case reviewed by the neurosurgical team at the Mayo Clinic in Mn. Yes, we have some very talented surgeons and very sophisticated equipment, but our actual knowledge of how the body works is very limited.

I have tons of anecdotes, but I’ll give just one… After getting an MRI I went to a neurosurgeon for his opinion and he wanted to do a surgery call a Laminotomy (grinding away some bone) at L4. I then went to orthopedic surgeon who reviewed the same MRI and saw nothing remarkable and recommended no surgery. I went to a third doctor to try and get consensus and after reviewing the SAME MRI recommended a 3 level Laminectomy (spinal fusion)… Three doctors, three different answers…

Long story, but after 7 years and two surgeries (not back surgery) I finally have a correct diagnosis .. But they cannot fix the problem nor explain why for 55 years I had no pain…. Thank goodness for Vodka !!!!

Anyone have any spare Leaches?………

A physical therapist came into work and talked with the group. She pointed out that sometimes working out in the gym can have negative effects as it causes muscles to get used to working in a shortened position. Not saying workouts are not beneficial. We got some good advice and coaching on using body weight exercises. Not trying to pitch anything, just wanted to pass along something I found helpful.

http://www.mihp.net/store/daily-dozens/category/2/movewell-daily-dozen-downloads.html

Apologies for offering unsolicited medical advice, but have you tried chiropractic? Pain radiating down the leg is a common symptom treatable by chiropractic (non-invasive, and not expensive – to keep this posting on economic issues) techniques.

Full disclosure: my wife is a chiropractor.

My comments were made with the idea of exposing the amount of medical knowledge we actually have vs how much we spend chasing false promises.. Did not want to make this about my case (I’ve talked about it so much… Even I get bored talking about it !!! LOL)

As I mentioned in my post, I tried a litany of non medical things BEFORE going to medical doctors

including but not limited to PT and Chiropractic… But I thank you for your concern.

If we look at the main drivers of cost.. Cancer, stroke, Heart disease and diabetes.. They ALL are life style/ diet related…. If we consumed less, consumed better and exercised more we could reduce the amount spent trying to resolve/treat these things after the fact.

Karl Denninger at another site makes a strong case that failure to enforce Sherman and Robinson Patman anti trust laws is a primary driver of cost.

`

70 years of independence just recently celebrated and India is still so far behind. Seriously, this country needs to get its s**t together.

unequal distribution of spending on individuals is the norm in systems in which the majority of spending is for allopathic curative care. For all the talk of prevention and primary care, etc., the fact of the matter is that in any given year a small percentage of the population will account for a large proportion of health care spending.

It’s the nature of disease and injury. It’s also the theory behind insurance (everyone pays in so the money is there when you need it). Cancer care, end stage renal disease, severe trauma, all cost hundreds or even thousands of times more than your flu or my broken toe.

This is not to deny the health care catastrophe engendered by unequal, unfair access to services. But high utilizers using health care doesn’t drive the cost spiral.

The difference between the US and other societies is that we rely on vert lightly regulated private sector health insurance to distribute access, and our provider and pharmaceutical oligopolies are far less regulated than others. What Woolhandler and Himmelstein call “administrative costs” is actually pure rent-seeking.

Private sector insurers literally add no value — zero — to the economy. Their extractive skills are so extreme that Congress had to pass laws to actually require them to spend money on actual health care (caps on “medical loss ratio). That says it all — we entrust the financing of health care to entities that are so predatory that we then have to pass laws to force them to do the task that our society has entrusted them with.

According to new data from Cooper et al, a study based on nearly 4 billion individual private sector claims, market power (not quality, reputation, size, teaching status) is the single strongest predictor of hospital prices, and hospital prices are the strongest predictor of regional differences in costs.

And, of course, we’ve given pharmaceutical companies evergreen licenses to charge monopoly rents. No rational society would constrain its largest health care program from negotiating drug prices.

Structural market failure, monopoly and unregulated rent-seeking. US health care in a nutshell.

No tinkering with structured “marketplaces” no half-assed “public option” will fix this.

It seems that looking at the MEDIAN health care spending vs. life expectancy for various countries would paint quite a different picture of the efficiency of our health care systems.

And how come we don’t allow Medicare to pay foreign doctors and for foreign Medical Care. I see many patients who through some connection to their relatives qualify for Medicare and they live in foreign countries. I see many retirees who live in foreign countries who have to come back for medical care. Just doing that alone would at least set up some standard of comparison financially unless the overseas doctors and hospitals got smart and started charging like American ones because just because you are overseas does not mean you cannot game the system.

I agree that we need to be careful when correlating life expectancy to medical care (cost, availability, etc.). I have lived in Europe for most of my life and I can attest to the fact that for a long time health care in Spain, for example, under Franco and for years afterwards, was technologically way behind and you had to have money in order to pay for private care or travel to another country. In France, except for certain big cities with universities and big private medical centers, dental and eye care was bad to non-existent until recently (the last 15-20 years). In Italy things were much worse. I can tell blood-curdling stories about the hospital system in Rome in the 80’s. Yet the charts above show that in terms of life expectancy Italy and Spain are way ahead of France, where care has traditionally been better,

Which means that we should listen to specialists who stress the importance of life-style and preventative care over all the rest. It’s surely not a coincidence, for example, that in Europe Italian women have the lowest rate of obesity.