By C.P. Chandrasekhar, Professor of Economics, and Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Cross posted from Business Line

On 14 December 2016, in a widely predicted move, the US Federal Reserve announced that it is raising the federal funds rate by one quarter of a percentage point, taking its target band for short term interest rates to between 0.5 to 0.75 per cent. More importantly, it signalled a change in the stance of monetary policy, by suggesting that there are likely to be three more rate hikes over 2017, and predicting that the long term interest rate, which has been in decline, would rise to 3 per cent.

There has in recent times a growing consensus that the US Fed has continued with a loose monetary policy, with near zero interest rates and ample liquidity, for far too long. Low interest rates and large scale bond buying had led to asset price inflation that increased inequality and threatens another melt down in financial markets. Yet, each time the Fed was expected to reverse the low interest policy, it held back claiming that it feared it would abort a halting recovery from the Great Recession.

That fear has not gone away. While there is talk that the US economy has recovered enough to approach near-full employment with a tight job market, that view does not take account of the large numbers who had dropped out of the labour market during the recession and need to be brought back to restore pre-crisis employment levels. The real reason that the Fed has chosen this time to go the way it should on the interest rate front is the conviction that political circumstances have shifted focus from monetary to fiscal policy when it comes to spurring growth. The source of this conviction is the Trump campaign that promised to cut taxes and boost infrastructural spending to stimulate growth.

Trump’s victory based on an economic platform that promised such a stimulus, if implemented, would amount a major reversal in the macroeconomic stance adopted by developed county governments for quite some time now. Other than for a brief period immediately following the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, the stance adopted involved downplaying a proactive fiscal policy and emphasising the role of monetary policy in the form of infusion of cheap and easy money into the system to push debtfinanced private spending and growth. Trump claims that what needs to be done is to stimulate demand and incentivise private investment with tax cuts and drive growth and jobs with substantially enhanced infrastructural spending. The logic of how this strategy could be pushed without a runaway increase in federal deficits and public debt, which financial investors and many in Trump’s transition team would object to, is nowhere near clear. There is little reason to believe that Trump himself would want to displease finance capital by allowing deficits to widen, especially given his decision to appoint ex-Goldman Sachs partner and hedge-funds manager Steven Mnuchin as the Treasury Secretary in his administration.

That generates much uncertainty on what economic policy would really look like under the Trump administration. The Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen underlined this when she said that: “All the (Federal Open Market Committee) participants recognize that there is considerable uncertainty about how economic policies may change and what effect they may have on the economy.” Despite that uncertainty, and leveraging the evidence of recovery in the US, the Fed has clearly decided to hand 2 over the task of sustaining and building on that recovery to the fiscal policy that would be pursued by the Treasury under Donald Trump. There are no guarantees, however, that the Trump’s spending programme will be implemented and whether it will make any difference to the performance of the economy if it is.

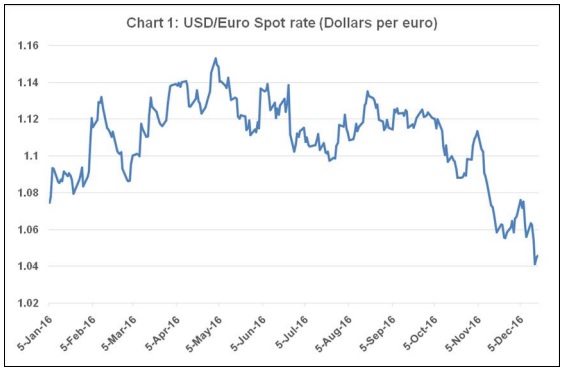

The problem here is not only for the US. It is for the rest of the world economy— especially Europe and Japan that are still mired in recession and emerging markets that have lost their post-crisis buoyancy. The immediate impact of the rate hike has been continued strengthening of the dollar against all other currencies, extending the gains it has made when differential economic performance and the flight to safety had increased investments in dollar denominated assets. This trend has now gone far enough to take the euro to below 1.04 dollars per unit, reviving discussion of euro- dollar parity (Chart 1). Elsewhere, Japan has seen a considerable weakening the yen as well, reflecting similar tendencies.

The trend to euro-dollar parity is the result of the contrary policy direction in the US and the Eurozone. While in the former moderate growth has led to a reversal of the low interest rate regime, in the latter, worsening economic conditions have led to the adoption of a negative nominal interest rate regime with multiple rounds of quantitative easing or loose monetary policy. The same is true of Japan, where the government is struggling to get inflation up to a targeted 2 per cent.

Under normal circumstances this should be a positive development for the slowly growing economies within the OECD, since a weakening currency relative to the dollar can make their exports more competitive. However, two factors are likely to limit this benefit. The first is that since currencies of countries outside the OECD are depreciating as well, the benefits of a strong dollar in terms of enhanced exports from counterparty countries could flow to them rather than the beleaguered European economies. Second is that having won an election on a platform that promised to increase jobs in America and keep them away from migrants, the Trump administration would be under pressure not to hand over the benefits of an improving economy to foreigners. If the rising dollar does lead to falling exports from the US, protectionism is a real possibility. That would only increase uncertainty in the world economy, as predictions of policies implying “de-globalisation” turn true.

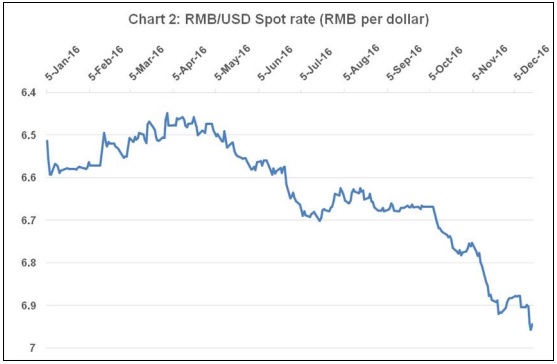

That uncertainty is affecting the so called emerging market economies (EMEs) through a route that can be even more damaging. This is through a preemptive surge in net outflows of capital that are in some instances rapidly depleting reserves. A surprising case here is China, which appeared to be sitting pretty on the external front with large foreign exchange reserves, a current account surplus, and a strong currency. But ever since the one-off devaluation of the renminbi (RMB) in 2015, as part of an effort to achieve market economy status, internationalise the RMB and have it included in the SDR basket, there appears to be a loss of confidence in the stability of the currency. As a result, the RMB has been losing value relative to the dollar in recent times (Chart 2). That matters because external financial liberalisation has opened avenues for resident firms and individuals to transfer money and wealth out of the country into assets presumed to be safe.

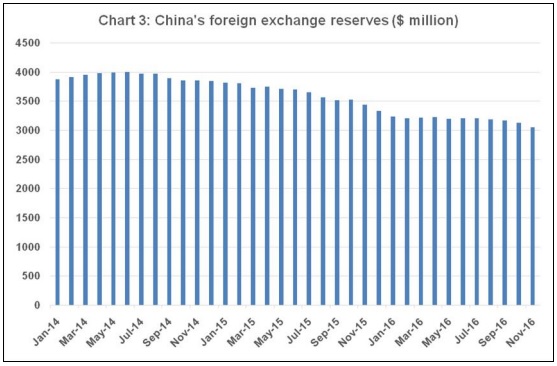

Thus, China now seems to be confronted with a situation of capital flight. Over the first 10 months of 2016, capital outflows from China totalled $530 billion. Foreign exchange reserves which had peaked at $3.99 trillion in January 2014, have fallen by from 3.23 trillion in January 2016 to 3.05 trillion in November (Chart 3). The government has responded with the imposition of capital controls, realising that the international context today is not best suited to efforts at globalisation including internationalisation of the renminbi. It has required approvals for purchase and repatriation of foreign exchange, including for payment of dividends to foreign investors. Curbs have been placed on gold imports and investments abroad in mergers and acquisitions are under scrutiny. Clearly de-globalisation is not a phenomenon restricted to either the UK after the Brexit vote or the US after the rise of Trump.

For those in each of the world’s nations who have suffered much from the loss of sovereignty and domestic policy space, this trend should be welcome. But what the process of transition would imply is extremely uncertain, with indications that its costs can be substantial.

i like reading the viewpoints from the non-Northeast Academia/echo chamber.

keep it up.

I guess the fed can’t do everything, and policy makers have relied on them for way too long in this time of being poorly led by the credentialed class. Somehow someone needs to find another way to drive growth. I think the consensus “around here” as the sore losers like to refer to nc, is that there are plenty of policies that can be implemented since the us has sovereign borders and a sovereign currency and can at the flip of a switch expand growth through deficit spending by simply giving money to poor people (BIG), hiring gardeners and staff for all the parks (JG). They could also shuffle the current money supply around by increasing the min wage or raising taxes (which is happening, but is really just taking some from one and giving it to others, not actually creating cash but redistributing in a closed system since deficits are apparently more evil than satan) Had the fed taken away the punch bowl then policy makers would have had to come up with some solutions, but no, so they have a fair share of the blood on their own hands. We all know what policies they chose instead which were failures as the article makes reasonably clear. The incoming administration can take the bit between their teeth and solve some of those issues if they feel like it. For instance, high medical costs can be eased as well as drive growth if health care workers have their student loans discharged, freeing cash that already exists in the system to be spent to drive consumer growth, in exchange for cheaper service. This can be achieved also at the flip of a switch by making eligibility for medicare apply to newborns and up rather than only to the aged who manage to make it through the gauntlet of the trials of years. Indeed all student debt should be dispatched as it harms growth in all sectors other than academia and finance. College costs would never have risen so much without the punch bowl of student debt, and a follow on is that rents also would never have gotten so high without giving what appeared to 18 year olds to be free guaranteed money but which is actually a ball and chain and a cudgel that can never be extinguished. Will they do it?

But ever since the one-off devaluation of the renminbi (RMB) in 2015, as part of an effort to achieve market economy status, internationalise the RMB and have it included in the SDR basket, there appears to be a loss of confidence in the stability of the currency. As a result, the RMB has been losing value relative to the dollar in recent times (Chart 2).

Chart 2’s left hand scale shows that on 01/06/16 the RMB/USD spot rate at a little over 6.5 and on 12/05/16 the spot rate is 6.95 which implies the RMB has been gaining value relative to the USD over that time period. I suspect chart 2’s left hand scale has been inverted.

Thus, China now seems to be confronted with a situation of capital flight. Over the first 10 months of 2016, capital outflows from China totalled $530 billion. Foreign exchange reserves which had peaked at $3.99 trillion in January 2014, have fallen by from 3.23 trillion in January 2016 to 3.05 trillion in November (Chart 3).

Over the first ten months of 2016 money outflows were $530 billion, yet foreign exchange reserves went from $3.23 trillion to $3.05 trillion, a difference of $180 billion in eleven months implying money inflows during the roughly same time period of $350 billion. From January 2016 to September 2016 on chart 3, if accurate, China’s foreign reserves appear stable with money coming in equaling money going out, with the final 3 months of 2016 showing an increasing and accelerating amount of money going out.

The implication of this, is that the money flowing out isn’t being used to buy inputs into China’s sweatshop to the world, but to get as much out by the Chinese leaders as they possibly can, which means asset price inflation wherever that money goes. No price is too high when paying with loot.

Once this phenomenon burns itself out, asset prices go down and the loot goes up in smoke.

That’s the Fed’s certainty principle.

‘On 01/06/16 the RMB/USD spot rate at a little over 6.5 and on 12/05/16 the spot rate is 6.95 which implies the RMB has been gaining value relative to the USD over that time period.‘

When it takes 6.95 yuan to buy a dollar instead of 6.50 yuan before, then the yuan has weakened to being worth 14.3 cents (1 / 6.95) from 15.4 cents (1 / 6.50) before.

The chart’s left hand scale is inverted so that the downward direction corresponds to a weaker yuan vs the USD.

Thanks Jim. My words are farts in the wind, blowing back at me.

“Age of Uncertainty”? “Widely predicted move”? “Change in stance in monetary policy”?

ha ha hahahaha…whoo, let me catch my breath.

Another economist heard from with more pointless commentary about things he is unable to predict as evidenced by his inability to predict anything to date. This includes events and the effects of those events.

“Target band of 0.50 t0 0.75”. LOL. Is that how dreadful our economy has become where our banks and major companies can’t survive without negative real interest rates? How can negative real interest rates possibly serve any good purpose?

Trump is welcome to hand over the “benefits” of our economy to foreigners.

yeah more pointless commentary and I love how they pretend they still control interest rates with this “target band of .5 to .75” nonsense. There is no real fed funds rate to target since fed funds don’t even trade in a system flooded with nearly $3.0 trillion in excess reserves. They have to fake like they have control by paying interest on excess reserves which now amounts to a massive give away to the banking system of something like $25 billion at this point, all at taxpayer expense mind you since this money would normally be remitted back to the treasury. They also use their reverse repo program as part of the scam to pretend as if it is business as usual. I can never get over how the morons in the financial media never pick up on any of this. I guess the wizards still have them bamboozled.

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Irving Fisher 1929.

Irving Fisher’s belief was based on an absolute faith in markets based on neoclassical economics which states markets reach stable equilibriums.

In 2007, Ben Bernanke could see no problems ahead.

Ben Bernanke’s belief was based on an absolute faith in markets based on neoclassical economics which states markets reach stable equilibriums.

Neoclassical economics is as bad as its always been and leads you to believe you can create real wealth from inflating asset prices.

This hasn’t been true since Tulip Mania in 1600s Holland.

Wealth – real and imaginary.

Central Banks and the wealth effect.

Real wealth comes from the real economy where real products and services are traded.

This involves hard work which is something the financial sector is not interested in.

The financial sector is interested in imaginary wealth – the wealth effect. Hardly any of their lending goes into productive lending into the real economy.

They look for some existing asset they can inflate the price of, like the national housing stock. They then pour money into this asset to create imaginary wealth, the bubble bursts and all the imaginary wealth disappears.

1929 – US (margin lending into US stocks)

1989 – Japan (real estate)

2008 – US (real estate bubble leveraged up with derivatives for global contagion)

2010 – Ireland (real estate)

2012 – Spain (real estate)

2015 – China (margin lending into Chinese stocks)

Central Banks have now got in on the act with QE and have gone for an “inflate all financial asset prices” strategy to generate a wealth effect (imaginary wealth). The bubble bursts and all the imaginary wealth disappears.

The wealth effect – it’s like real wealth but it’s only temporary.

With bubble bursting interest rate rises, the fun is just beginning.

The markets are high but there is a lot of imaginary wealth there after all that QE. Get ready for when the imaginary wealth starts to evaporate, its only temporary. Refer to the “fundamentals” to gauge the imaginary wealth in the markets; it’s what “fundamentals” are for.

Canadian, Australian, Swedish and Norwegian housing markets are full of imaginary wealth. Get ready for when the imaginary wealth starts to evaporate, its only temporary. Refer to the “fundamentals” to gauge the imaginary wealth in these housing markets; it’s what “fundamentals” are for.

Remember when we were panicking about the Chinese stock markets falling last year?

Have a look at the Shanghai Composite on any web-site with the scale set to max., you can see the ridiculous bubble of imaginary wealth as clear as day.

The Chinese stock markets were artificially inflated creating imaginary wealth in Chinese stocks, it was only temporary and it evaporated.

It’s what happens (in the real world, not the FED models).

Ah yes, the “Uncertainty” canard repeatedly used by the Fed chair and various FOMC members as the primary reason to maintain the status quo monetary policies in perpetuity, and more recently to verbally oppose increased domestic fiscal spending on infrastructure or for a multitude of other beneficial public purposes. For the past eight years, we have so looked forward to the days of certainty that surely lie just around the corner. But while inflation of financial assets has been underway as the years of ZIRP have passed, in the bubblelicious zone for the third time in the past couple decades, the Velocity of money remains in terminal decline, resting comfortably in those lovely, inflated, socialized stock and bond markets so beloved by the 0.1 Percent. Gah…Gah… Golly!… What policy actions might increase the Velocity of money?

What policy actions might increase the Velocity of money?

But, but, but China would benefit…….

Oh that’s so funny. “Wisdom of the Fed.” LMAO.

I’d accuse them of using Chrystal Balls, but Yellen does no have any.

This too is hilarious:

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Irving Fisher 1929.

Irving Fisher’s belief was based on an absolute faith in markets based on neoclassical economics which states markets reach stable equilibrium.

First let’s discuss austerity, and lack of demand:

Q: Who benefits from increased demand?

Could it be China? Do the PTB in the US want China to benefit?

Once that question is asked, then continue to ask yourself about the US’ troop deployment for “exercises” in Ukraine, and the Armored Column being deployed in Poland, coupled with the incessant Casus Belli on the Russian them. This kind of planning takes months if not years.

Somewhere behind all this is a 3 or 4 year long plan, with the overthrow of the Ukraine Government some few moths before their re-election, which they looked sure to lose.

These people only look stupid when they want to avoid blame.