By Ian Fraser, Twitter @ian_fraser. This piece, cross-posted from Ian’s web site. is a fully revised, updated and extended version of ‘Mafioso bankers and my part in their downfall‘ published in the Sunday Herald on 5 February 2017

On Thursday 2 February, two former senior bankers at Halifax Bank of Scotland (HBOS) and four consultants with whom they closely worked were jailed for periods stretching from three-and-a-half year to 15 years for their part in a £245 million loans scandal.

Four days earlier, the ‘HBOS six’ were found guilty of offences including corruption, fraudulent trading and money laundering – offences that caused losses of up to £1 billion at HBOS’s parent, Lloyds Banking Group, and caused the destruction of up to 200 viable small-business customers of the bank’s. For me, it was the culmination of an investigation with which I’d been involved for almost a decade as a journalist.

Seasoned journalists often say “never look below the line; that way madness lies”. They mean that you shouldn’t read the comments underneath articles you’ve written – as they can be minefield of pedantry, grandstanding, semi-coherent rage and abuse. So when I saw that my “Call to sack HBOS directors” article, published in the Sunday Herald at the banking crisis’s nausea-inducing height on 28 September, 2008 – days after HBOS had collapsed and when RBS was perched on the brink – had over 400 comments under it, what did I do?

I ignored colleagues’ advice and delved in. Amid the bluster and outrage that an iconic 300-year-old Scottish institution should have been led to destruction by such hopeless directors as Lord Stevenson and Andy Hornby, one short comment stood out. It was from a Cambridge-based businesswoman called Nikki Turner, and read “if anyone is interested in finding out more a £1 billion fraud in a single HBOS branch, please get in touch.”

It didn’t take me long to contact her. On Tuesday, 30 September, I had several long phone calls with both Nikki, a lyricist and a mother of two daughters, and her husband Paul, a rock music entrepreneur who had done the lighting for acts including Bob Marley, Dire Straits, The Jam, Fleetwood Mac, Thin Lizzy and Bruce Springsteen. I learned the couple had launched an independent music label, Zenith Cafe, together in 2003. They told me this had been on the cusp of a major breakthrough in 2007 when, for no apparent reason, HBOS and its preferred management consultants had tried to snuff it out.

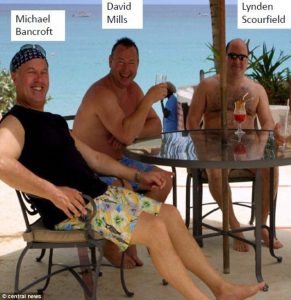

The Turners blamed this on a rogue Bank of Scotland senior manager whose improbable name sounded like that of a Victorian villain – Lynden Scourfield. They alleged that Scourfield, lead director of impaired assets at HBOS’s Bank of Scotland Corporate unit, had been working in cahoots with a band of self-styled “turnaround consultants” dubbed Quayside Corporate Services, which was led by David Mills, who I later discovered had left his former employer, Lombard North Central, the factoring and invoice discounting arm of National Westminster Bank, under a cloud in 1995.

The seemingly wilful destruction of Zenith sounded bad enough. But what made me realise this story had legs was that the Turners had documentary evidence to back up every claim, and had already done a significant amount of research into the activities of Scourfield, Mills and Quayside. Critically, they had discovered that Zenith was not alone in having been treated shabbily.

They had identified dozens of other businesses across the UK which had been through the mill at the hands of Mills and Scourfield and, in many cases, the punishment meted out had been far worse than that endured by Zenith. The affected firms came from a wide range of sectors including aviation, consumer credit, music publishing, packaging, nightclubs, restaurants, sporting goods, textiles and top-shelf magazines – and included well-known brands like Smollensky’s on the Strand, Euromanx airline and magazine Asian Babes.

The modus operandi of the fraud, which I confirmed in interviews with directors of other affected firms, included that the companies would, often arbitrarily and without notice, see their bank accounts transferred to the tutelage of Mr Scourfield’s “high risk” team based at Beauclerc House, Reading. Many of the companies that were transferred were not in default or financial difficulties. Triggers included that they had sought additional facilities to fund acquisitions or growth, or just that Scourfield and his cronies had taken a fancy and had cherry-picked them from across the Bank of Scotland network.

The next step was that Scourfield would force the companies to adopt Quayside personnel as advisers, shadow directors or directors, effectively using blackmail to ensure the companies acquiesced. The standard threat was, if they did not comply, they would be “shut down”. With Quayside in the driving seat, Scourfield would then turn on the monetary taps, granting huge and usually unserviceable additional loans to the firms concerned, a process sometimes eased through by the writing of fake business plans, which Scourfield used to placate his seniors in the bank. Those who were responsible for signing off his loans are believed to have included Paul Burnett, who wound up working for Mills.

The next thing that the legitimate owners and managers of the affected firms knew was that Quayside personnel – the most unsavoury of whom were David Mills, Michael Bancroft and John “Tony” Cartwright – started behaving liked trumped up Mafiosi, treating the companies as their own personal ATMs and syphoning out cash, dressed up as “consultancy fees”, to fund lavish lifestyles, exotic holidays, foreign real estate buying binges and romps with high-class hookers as well as generous bribes and “inducements” along similar lines for Scourfield, who was sometimes also known as “Gerard”. All the while, Mills and Co were destabilizing the businesses, plundering their assets, and setting them on a path towards insolvency.

One reason Scourfield and his subordinate Mark Dobson were able to get away with this sort of thing was that the checks and balances within Bank of Scotland Corporate were either weak or non-existent. During the recent trial, it emerged that, during 2003, an internal auditor at Bank of Scotland Corporate alerted his superiors to the fact the CODA financial reporting system, which was supposed to flag up unexpectedly large loans, was “broken”, and that the bank failed to repair it. It has yet to emerge whether this was a deliberate oversight on the part of the bank — but it certainly suited Scourfield and probably loads of other people within Bank of Scotland Corporate. Furthermore in the three years between 2004 and 2007, it emerged that the Reading office that Scourfield ran wasn’t audited once!!

Some of the firms’ legitimate owners and managers told me they felt like they had been overrun by the mob, with metaphorical “guns” frequently “held to their heads”. Others said they they felt like they’d entered a Kafkaesque nightmare, especially when their complaints to HBOS’s headquarters on Edinburgh’s Mound fell on deaf ears. I was shocked that a supposedly reputable bank, founded in 1695 and which once advertised itself as “A Friend for Life”, should have given a gang of utter reprobates free rein to ride roughshod over its small and medium-sized enterprises base, but have studiously ignored the victims’ cries of help.

The Turners’ tale might have been possible to dismiss as a sob story, a failed business blaming its woes on a bank, allied to a wild conspiracy theory that could not possibly be true but, unlike some other journalists they approached, I was fairly convinced this was not case. This was something major and abhorrent, which I felt was crying out for exposure, especially since the bank seemed so desperate to keep it under wraps. I also felt that, since HBOS was about to be acquired by Lloyds in a “shotgun wedding” demanded by UK prime minister Gordon Brown, that Lloyds TSB shareholders deserved to know of the true toxicity of the bank they were being expected to absorb.

The Turners had issued a formal complaint, which detailed the scale and scope of the alleged internal fraud, to all sixteen members of HBOS’s board, including chairman Lord Stevenson, chief executive Andy Hornby, finance director Mike Ellis and non-executives Sir Ron Garrick and Charles Dunstone on 3 September 2007, sending the letters by both email and recorded delivery. The bank’s response was astonishing.

Instead of thanking them for alerting it to alleged criminal wrongdoing, reporting the perpetrators to the police, and seeking to put things right, HBOS sent a menacing legal letter via the ‘silver circle’ solicitors Denton Wilde Sapte which, among other things, invited the music industry duo to notify and provide evidence to the police if they believed that crimes had occurred. Then, in an apparent campaign to silence the Turners, HBOS through solicitors Wragge & Co but with Dentons also in attendance, sought to have them evicted from their home and place of business in 22 subsequent court hearings.

This was despite the fact their inability to service their mortgage had been caused by the destruction of their business by Scourfield and Quayside!

After the Turners reported the alleged fraud to the Cambridgeshire Constabulary three months later, the police approached the Edinburgh-based bank to find out what was going on. But the bank’s Corporate Financial Crime Prevention team sought to put a lid on things by claiming that no criminal activity had taken place, a claim that put the cops off the scent. Unless the alleged crime was reported by its largest “victim”, no criminal inquiry could proceed. In an email dated 21 April 2008, Brenda McMeechan, investigations manager in HBOS’s corporate financial crime prevention team told police who were making inquiries:

“I would advise that we are not undertaking an investigation into Lynden Scourfield’s conduct, as we have no evidence of criminal activity on his part. Without proof to corroborate any act of deception or fraud, I cannot offer any information that would support or substantiate any allegations of wrongdoing.”

It later emerged that Lloyds, which completed its highly contentious takeover of HBOS on Monday, 19 January 2009, thereby assuming full responsibility for addressing the matter, had also been obstructive. Anthony Stansfeld, police and crime commissioner of Thames Valley, later suggested that the Gresham Street-headquartered bank was uncooperative during the subsequent police probe. He said Lloyds “made every effort to make it difficult for the police to investigate … Everything was put under legal privilege — it required a host of barristers and lawyers to untangle it and get it out of the bank,” he said.

As a financial journalist I was well aware that reckless lending, inadequate controls and delusional thinking had fuelled the UK’s banking crisis. But what I had learned since first picking up the phone to the Turners seemed off the scale. To summarize, Mills and Co were acting like the gangsters in Martin Scorsese’s classic movie, Goodfellas, in which Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill and Paul Sorvino’s Paul “Paulie” Cicero take over a night club, the Bamboo Lounge, then loot it, abuse the owner’s credit and run it into the ground. Once the owner, Sonny, is unable to pay them anymore, they torch it for the insurance money. As Liotta’s Hills narrates: “And, finally, when there’s nothing left, when you can’t borrow another buck from the bank or buy another case of booze, you bust the joint out.”

My next task was to try and get the story published. Sunday Herald editors Richard Walker and Stephen Penman, who I met in Glasgow on 7 October, gave me the go-ahead to research and write a major investigative piece alongside experienced investigative journalist Paul Hutcheon. Paul and I made excellent progress over the next few weeks, poring over publicly-available data from Companies House, interviewing a dozen or so businesspeople who had been stripped of their assets and impoverished, marshalling other evidence from victimised firms, persuading a whistleblower named Terry Holligan who had worked alongside Michael Bancroft as managing director of Quayside-controlled textiles group Magenta Studios to come up to Glasgow to provide an affidavit about brown envelopes of cash plundered from that and other companies being used to pay for Scourfield’s high-class hookers and much, much more.

I managed to track down Mills and asked him to respond to allegations that he had destroyed businesses, seized assets, and gouged millions of pounds from firms he was supposed to be caring for. In an interview on 27 November 2008, Mills claimed that the “whole principle” of Quayside was “to come in and actually get [the companies] through a difficult period.” “You could speak to many other chairmen and managing directors of business who would tell you they are absolutely delighted with the services Quayside provided because it saw them through a difficult time.” It seemed like he was lying through his teeth, and this was confirmed when, during the recent trial, Bank of Scotland Corporate’s impaired assets director Tom Angus conceded to the jury that, as far as he knew, Quayside had never restored a single client of the bank’s back to health.

I managed to track down Mills and asked him to respond to allegations that he had destroyed businesses, seized assets, and gouged millions of pounds from firms he was supposed to be caring for. In an interview on 27 November 2008, Mills claimed that the “whole principle” of Quayside was “to come in and actually get [the companies] through a difficult period.” “You could speak to many other chairmen and managing directors of business who would tell you they are absolutely delighted with the services Quayside provided because it saw them through a difficult time.” It seemed like he was lying through his teeth, and this was confirmed when, during the recent trial, Bank of Scotland Corporate’s impaired assets director Tom Angus conceded to the jury that, as far as he knew, Quayside had never restored a single client of the bank’s back to health.

HBOS’s response was no less disingenuous. Its spin chief Shane O’Riordain gave us a statement which read: “We deal in a sensitive and fair way with all our corporate banking customers, including those experiencing difficulties … We do everything in our power to reassure customers while, at the same time, helping them to turn around their business. We simply cannot comment on individual circumstances. However, we strongly believe that we have acted throughout in a fair and responsible way.

“Turnaround consultants or professional advisors are a recognised resource available to companies who may be facing financial difficulties. It is a normal approach for both companies and the bank to mutually engage with such individuals in an attempt to work through their difficulties. In your letter you referenced a former employee of Bank of Scotland who was based in our Reading office. We do not intend to name the individual but can confirm that this colleague left the group some months ago.”

While we were prevented by in-house lawyers from using some of the material, two lengthy pieces titled “HBOS faces hard questions overuse of troubleshooters who misappropriated company money” and “All they seemed to do for us was to take enormous fees” were published in the Sunday Herald on 30 November 2008. Among other things, we managed to break the news that two of Quayside’s consultants, Bancroft and Cartwright, had a history of embezzlement having stolen more than £1.5 million from textiles group Ritz Design PLC in 1991 and to convey the suffering they had inflicted on affected firms. (Incidentally I remember, on the Saturday before these articles were published, while on a hike in the Pentland Hills, having to spend what seemed like hours on the phone to Sunday Herald editor Richard Walker and a solicitor retained by Newsquest Herald & Times, who were wanting to check up on certain facts and claims).

Perhaps naively I had been expecting the articles to create waves and to jolt the bank and/or the authorities out of their complacency. But, partly because we had been unable to convey the full extent of the fraud and subsequent cover up, the story wasn’t widely followed up (indeed, I believe the only paper that did follow it up was the now defunct Manx Herald). Unfortunately it had nowhere near the expected impact.

In early March 2009 I was invited by the BBC Investigations Unit to help make an investigative documentary on the scandal. From March to May I worked alongside a team of BBC staffers including Karen Kiernan, Alan Clayton, Alan Urry and team leader and assistant editor of the investigations unit, Lynne Jones. The tasks I was given included researching what had happened at the Quayside-controlled textiles group Magenta Studios which, after being milked for all it was worth and destabilized by Quayside over a four-year period, was driven into administration in early April 2007. Another was to research what sort of checks and balances were supposed to exist in Bank of Scotland Corporate.

At Magenta Studios I learned that Quayside’s Bancroft had been helping himself to fees of some £15,000 to £20,000 a month, and probably much more, even though he was having an entirely negative effect on the business. As a result of behaving like a sociopathic bully he had alienated key staff and customers, causing the company to lose two of its biggest customers, Marks & Spencer and Next, which in turn caused turnover to slump from £8m to less than £2m. Meanwhile Magenta Studios’s borrowings from Bank of Scotland Corporate were going through the roof, soaring from £5m to £20.564m between 2003 and 2006. One source formerly at the company told me: “Bancroft was paranoid. He didn’t trust anybody. I don’t think he cared a toss about the company”.

The source added: “I think Bancroft was charging exorbitant fees but doing f**k all for it. He only came to the company occasionally, when he felt like it, and didn’t do anything apart from just sit around talking. He was not instrumental in any new business or any initiatives. He was just trying to get money out for himself in fees and expenses. He even gave his daughter a job with the company, for which she was paid £33,000, but all she seemed to do was go shopping.”

Within a few days of Scourfield being “rumbled” and ousted, I discovered that Magenta Studios and a number of associated textiles business that had fallen prey to the fraud (including Theros, Multi Sourcing Group and Kangaroo Poo) had been swiftly forced into administration by the bank. Oddly, the administrators, appointed on 10 April 2007, the day after Bancroft is alleged to have scrubbed the hard drive on his computer in what has been described as a bid to eliminate evidence of the fraud, were KPMG’s David Crawshaw and Jane Moriarty. Scourfield had described David Crawshaw as “a close friend of mine” to one of the many victims of the fraud.

The picture I was getting about the systems and controls at Bank of Scotland Corporate was no less shocking. An obsession with growing its market share in UK business banking, in a crazed, “growth at any cost” strategy laid down by HBOS chief executive James Crosby, had been the bank’s key driver ever since the Halifax merger of 10 September 2001. As a result, systems and controls had atrophied or, as the CODA scenario makes clear, were readily over-ridden by any bonus-crazed insider.

I also identified that HBOS was using unorthodox ways of massaging down its bad debt provisions in order to misrepresent its financial position to regulators and shareholders and inflate executive bonuses. I had exposed similar shenanigans at the bank in an earlier article, ‘Keane’s Last Stand‘, published on 29 August 2004. These included “rolling over” non-performing loans and a range of other ruses, including the use of off-balance-sheet vehicles to hide rancid loans and to avoid the crystallisation of bad debt.

A senior insolvency expert told me during the course of my research that HBOS was well-known in banking and insolvency circles for keeping insolvent business borrowers going, just so that the bank could book the interest payments as profits, and hide bad debts. He said this was illegal both for the company directors concerned and probably also for the bank. He knew of actual examples of companies where it had happened — where a professional advisory firm had told the bank a business borrower was bust, but the bank had ignored the advice and continued to lend. The senior insolvency expert added that “HBOS’s approach towards distressed corporate customers would have been set at the highest levels by George Mitchell (chief executive of Bank of Scotland Corporate until December 2005) and his successor Peter Cummings.”

A forensic accountant retained by the BBC found that some 93 per cent of the £113 million that Scourfield had lent to the aviation business Corporate Jet Services, parent of Euromanx, had simply “disappeared”. One ex HBOS insider told me during the course of my research that: “They behaved in a very reckless fashion. Nothing was done properly.”

Two senior people within Bank of Scotland Corporate tried to put me off the scent, with one claiming that Scourfield was “a red herring” in that his £1bn losses played no part in the bank’s September 2008 collapse. And, in a letter to the MPs dated February 2009, Lloyds Banking Group’s chief operating officer for wholesale banking, Philip Grant, who it later transpired was previously with Bank of Scotland Corporate, insisted there was “a lack of evidence of direct personal benefit on the part of Mr Scourfield from his relationship with Quayside.” In his weasly worded letter to politicians Grant also claimed the bank had reached this conclusion following “an extensive internal review” after Scourfield quit in March 2007.

In his letter to MPs, Grant also said that: “While the bank appears to have been more supportive than it should have been in responding to requests for increased facilities, this occasioned loss to the bank, and there is no evidence that it led to the failure of already stressed businesses.” He also stated “there is no evidence that anybody at the bank knew, at that time, that the reputation of Quayside (or of individuals within Quayside) was in any way questionable.”

Seemingly desperate to downplay the scandal, Grant also said “In early 2007, the bank identified issues concerning Mr Scourfield’s approach to lending. As pointed out above, the bank was more supportive than it should have been in responding to requests for increased facilities from some of the customers in question. After Mr Scourfield had been suspended from duty on account of these matters, he resigned in late April 2007.” The statement was replete with half truths.

While researching the BBC programme we also discovered that HBOS had been using the Sandstone Organisation, a shadowy off-balance-sheet vehicle of which Mills seemed to have control, as a bounty box for the equity stakes and other assets seized from affected firms. In 2007, according to documents filed at Companies House, Sandstone’s only directors were Mills and his wife Alison, who was also on trial in Southwark Crown Court from September 2016, and last week was found guilty and sentenced to three-and-a-half years in jail. The company secretary at Sandstone was Mills’s daughter Georgina Elizabeth Paffard Mills, who was not tried.

Though references to “brown envelopes” for Scourfield and the procurement of sex workers for him using money plundered from affected firms ended up on the cutting room floor, our findings about rampant loan abuse, the plundering of cash and assets from innocent businesses and the human toll of this nefariousness were broadcast in a 40-minute BBC Radio 4 “File on 4” documentary on 26 May 2009. The programme was extensively followed up in other media including on BBC news bulletins.

A few days after the ‘File on 4’ was broadcast, the Conservative MP James Paice organised a parliamentary debate about the scandal, which was attended by about dozen MPs with constituents whose firms had been ruined as a result of the actions of HBOS and Quayside. During the debate, held in Westminster Hall on 2 June 2009, Paice asked: “If everything was satisfactory, why did HBOS stop using Quayside? I hope this debate demonstrates to the minister that he should invite the regulatory authorities to investigate the whole matter thoroughly. … All of us are taxpayers, and we are justified in demanding to know how that happened, why it was allowed to happen and whether any criminality was involved.”

Dr Andrew Murrison, Conservative MP for Westbury in Wiltshire, said: “It is simply not credible to characterize Scourfield as some autonomous rogue banker and leave the matter at that. Loans of that order must have been sanctioned and remitted at a much higher level—in this case, at HBOS headquarters in Edinburgh by Mr. Scourfield’s immediate superior at least …. It is evident that Mr. Lynden Scourfield had a close relationship with Quayside’s Mr. Bancroft and Mr. Mills. What remains opaque is the extent to which those now liquidated companies were acquired by undertakings associated with Quayside … Given the apparent murkiness of the situation, there is every reason for the FSA to undertake a comprehensive investigation, and I urge the minister to use his good offices to ensure that happens.

Ed Vaizey, Conservative MP for Wantage, said: “It is now up to HBOS to come to the table, following a moral course rather than a legalistic one, and put those people back in the position that they would have been in before dealing with HBOS.”

Occasionally when writing investigative pieces and updates on the unfolding scandal, I and others with whom I was working had moments of doubt. If Lloyds was denying any wrongdoing, if David Mills was claiming he was a legitimate turnaround specialist who had the best interests of affected firms at heart, and if no UK authority was bothering to investigate the scandal, then perhaps we were just delusional. Perhaps the dozen or so cases we had forensically investigated were just aberrations and Mills and his cronies really were decent coves who were genuinely aiming to restore the firms with which they became involved to health. It was a fantasy which generally did not last very long. There were also occasions when I feared for my own safety, after parties who had had dealings with Bancroft warned me that he and some of his Quayside colleagues were prone to violence, and I received menacing anonymous phone calls.

Between mid-2007 and mid-2010, as well as contacting the banks and the police, the Turners reported detailed findings of misconduct and criminal activity by HBOS and its retained advisors to solicitors representing the banks, the Financial Ombudsman Service, the Financial Services Authority, the British Bankers Association, the Department of Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR), the Chartered Institute of Banking, HMRC, the Serious Fraud Office, prime minister Gordon Brown, chancellor Alistair Darling, prime minister David Cameron, chancellor George Osborne, Bank of England governor Sir Mervin King, the Treasury Select Committee, the Treasury (who were forwarded their information by Gordon Brown), the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby and their MP Sir James Paice. With honourable exceptions such as King and Paice, most just played a game of pass-the-parcel, came back with disingenuous and meaningless waffle, or totally ignored their missives,

Separately, I sent a comprehensive briefing note to all members of the Treasury Select Committee on 9 February 2009, a similar note to the FSA’s chairman Lord Turner and chief executive Hector Sants on 11 June 2009, and sought answers from UK Financial Investments, the government agency responsible for husbanding the taxpayer’s stakes in bailed out banks, on 3 December 2009. The only reply, other than a “no comment” from UKFI’s spokesman Anthony Silverman, came from Sants, who replied on 1 July saying “thank you for the email you sent to me on 11 June in relation to the allegations made about the HBOS / Reading branch. I apologise for the delay in responding. The information you provided raises serious allegations and has been passed to our supervisory group for review. The supervisory group will, if appropriate, liaise with the police.”

In May 2010 I became so frustrated with the bank’s stonewalling that I obtained proxy voting rights from a Lloyds Banking Group shareholder and asked the bank’s board, then led by chairman Sir Win Bischoff, a few questions at its annual general meeting in the Edinburgh International Conference Centre. I said: “The Banking Code states: ‘We promise we will treat you fairly … We will lend responsibly … We will deal quickly and sympathetically with things that go wrong …’. In the light of this, do you believe that you have abided by these principles in your handling of the Bank of Scotland Corporate Reading scandal?” No sensible answers were forthcoming. When I spoke to Bischoff over coffee afterwards in the open-plan lobby of the EICC, he threw the question back at me asking “well, how would you have handled it?”

Scourfield used different methods in his attempts to silence me, including issuing a libel writ over something I had written in a blog at the time of the ‘File on 4’ programme in May 2009, with the full writ arriving by recorded delivery on 22 September 2010, just a week before he was arrested at his Berkshire home. However, this backfired spectacularly for Mr Scourfield, as it only added to my enthusiasm for getting the story out there, and obviously lapsed once he pleaded guilty last year. Now that he has been jailed for 11 years and three months, I intend to sue him for costs and damages incurred by his failed writ.

After a decade of denial and persecution of the victims, senior Bank of Scotland Corporate and Lloyds bankers finally owned up, under oath, during the recent trial, admitting that they first became “suspicious” of Scourfield and concerned about “many gaps in formal sanctioning” in January 2006. They conceded that they had launched the first of at least seven internal and external investigations (which were internal, and therefore suppressed until the court case) into what he had done in July 2006. The cumulative effect of the reports was that, by July 2007, according to Thames Valley Police, the bank should have concluded that fraud had taken place.

Throughout the four years that I was investigating this, I was genuinely shocked at the level of disinterestedness of the regulators including the FSA, to the extent I began to wonder whether they might be more interested in protecting the state-rescued bank than in getting to the bottom of the scandal or holding those responsible accountable.

The FSA may well have been compromised. In 2003, chancellor Gordon Brown made the bizarre decision to appoint the then HBOS chief executive, James Crosby, as a non-executive director on the regulator’s board, a role Crosby took up on 15 January 2004. The appointment came hard on the heels of claims from Crosby, made in a speech to a Merrill Lynch banking conference on 7 October 2003, that the UK government was guilty of “unnecessary meddling in the SME banking sector”.

After setting HBOS on a catastrophic course, Crosby handed the helm to the “wunderkind” Andy Hornby when he took early retirement from the bank in June 2006. He was promptly promoted to FSA deputy chairman, and chairman of its committee of non-executives, on 11 December 2007 and didn’t leave the regulator’s board until he was fired on 11 February 2009, after a few of his multifarious failings as HBOS chief executive were revealed to the Treasury Select Committee via the explosive written testimony of the bank’s former group head of regulatory risk, Paul Moore.

Moore had been personally fired by Crosby on 23 November 2004 after seeking to alert the Yorkshire-born actuary and other members of the HBOS board to the inadequacies of the bank’s control framework and that its obsession with sales and asset growth meant it had embarked on a suicidal course. By letter Crosby assured Moore that the decision to eliminate his role and replace him with someone with no knowledge or experience of risk management (the saleswoman extraordinaire Jo Dawson) was “mine and mine alone”.

There are a great many people who wonder whether, during his five years on the FSA’s board, James Crosby went out of his way to ensure that the already “light touch” regulator — where Sir Callum McCarthy was then the chairman and John Tiner the chief executive — was “zero touch”, or “please look away now” where the crimes and misdemeanours of the bank he mismanaged were concerned. There can be no doubt that the modicum of regulatory scrutiny that existed until December 2003 abated until February 2009 (for more detail on this, see “HBOS’s Calamitous Seven Year Life“).

Thames Valley Police, the force for which fictional Chief Inspector Morse works in the Colin Dexter novels and ITV television series, became involved under the auspices of “Operation Hornet” – which the force said was to probe “corruption and large scale fraud in connection with HBOS” – on or about 11 June 2010. On 14 June 2010, Thames Valley Police senior investigating officer Natalie Beresford–Bolton paid a surprise visit to the Turners at their home near Cambridge.

Beresford–Bolton told them that, while on a routine visit to the Canary Wharf-based regulator with her boss in late May 2010, she had identified Bank of Scotland Corporate Reading as an egregious case from a list of cases that the regulator had under “Section 166” review. After the FSA refused to furnish her with much in the way of documentation on the case (and it had a fair amount by this stage), Beresford-Bolton spent the next two weeks trawling the internet, where she read all my coverage of the alleged fraud, as well as blogs and links to source material compiled by Nikki Turner (who, incidentally, is a great writer). It was only after having reviewed this that she persuaded her bosses at Thames Valley Police, who included detective superintendent David Poole, that the case merited a proper probe (Poole and other senior policemen at Thames Valley later denied what Beresford-Bolton told the Turners was true).

The police made an initial series of arrests — Bank of Scotland Corporate director Lynden Scourfield, his wife Jacqueline, and John “Tony” Cartwright — on 29 September 2010. It was the first sign that the UK authorities had any interest in properly investigating the matter. This was a major breakthrough for me, the victims and others with an interest in seeing the perpetrators brought to justice. Though I did update a summary of what had happened at Bank Scotland Corporate, retitled Banking’s Abu Ghraib (3 October 2010), in the wake of these initial arrests, my ability to report on the unfolding scandal was constrained after that. There was, however, a window of opportunity between the arrests and charges being pressed, something which happened in January 2013, to cover a few broader aspects of the case, and I did so in four further articles for the Sunday Herald, where business editor Colin Donald was supportive and eager to carry on breaking new ground. The Herald pieces included two published in March 2011 and July 2011 which raised questions about the remit and scope of Thames Valley Police’s ‘Operation Hornet’ inquiry, which had been ratified by the Crown Prosecution Service and I believe also by the then attorney general, Dominic Grieve. Questions I raised in these articles included:-

- Why did Operation Hornet only cover the period between 2002 and the date Scourfield left the bank — 8 March 2007 — when the most severe financial damage was inflicted on affected firms in a series of administrations after he left?

- Why were certain key HBOS borrowers that Quayside controlled – including one or two notorious and egregious cases in which high-profile businesspeople were involved such as Corporate Jet Services – excluded from the Operation Hornet probe?

- Critically, why were the police not fully investigating the role of people higher up in the bank?

These questions formed the basis of my pieces Police dossier says former HBOS directors failed to act on fraud allegations (13 March 2011) and Board’s role ‘off limits’ in police probe of alleged £1bn HBOS fraud (10 July 2011). Also around this time I wrote a summary piece for Naked Capitalism headlined The £1bn-plus HBOS Fraud Investigation That Lloyds Keeps Trying to Brush Under the Carpet (2 March 2011). Then came the swansong Sunday Herald piece, headlined Corruption allegations, major fraud inquiries, links to pornographic magazines … and a luxury yacht (22 July 2012), which was written following a tip-off that charges were imminent.

There followed a four-year period of purdah, when it was impossible for me or anyone else to write anything substantive about the case, as to have done so could have been in contempt of court, or jeopardised Thames Valley Police’s investigation.

Now, after four-month trial in court five of Southwark Crown Court, ably presided over by judge Martin Beddoe, the purdah is over. The culprits have been jailed for periods of between three-and-a-half years and 15 years. I do feel a degree of vindication, especially since so few others dared touch this story between 2008 and 2012.

Judge Beddoe summed up the feeling of many with his sentencing speech last Friday, when he said: “This case is not simply about a corrupt bank manager lending money he should not have done to businessmen who went on to gamble with it.

“This case goes very much deeper than that. It primarily involves an utterly corrupt senior bank manager letting rapacious, greedy people get their hands on a vast amount of HBOS’s money and their tentacles into the businesses of ordinary decent people … and letting them rip apart those businesses, without a thought for the lives and livelihoods of those whom their actions affected, in order to satisfy their voracious desire for money and the trappings and show of wealth.”

“The corruption, which profited mostly the first three defendants, subsisted for at least four years. It involved Lynden Scourfield engaging in as extensive an abuse of position of power and trust as can be imagined and was motivated on both sides of the corruption by the expectation of, and the very considerable realisation of, immense financial gain. That was at the cost of enormous losses to Bank of Scotland of some £245 million [gross], but also and, in many respects worse, the destruction along the way of the livelihoods of a number of innocent hard-working people. Some of these connections were capable of rescue but what Lynden Scourfield let happen through David Mills and Michael Bancroft predominantly ensured that they would not.

“The harm for which you were individually and collectively are responsible can of course be quantified in cash terms, but cannot be so in human terms. Lives of investors, employers and employees have been prejudiced and in some instances ruined by your behaviour. People have not only lost money but, in some instances, their homes, their families, and their friends. Some who would have expected to be comfortable in retirement were left cheated, defeated and penniless. These are circumstances in which you David Mills and Michael Bancroft in particular show not a shred of remorse.

Beddoe also said that “much of what David Mills told the police has for the most part been proved to be a lie.” And speaking about Bancroft he said: “If members of Michael Bancroft’s family think he is an honest and lovely man they are sadly blinkered from reality, and their submissions give no consideration for the crimes he committed nor the damage and destruction he quite wilfully caused to his many victims.”

Addressing Scourfield, who unlike the other defendants had plead guilty (on 12 August 2016) and therefore had not taken any part in the proceedings, Judge Beddoe said: “Yours was a monumental betrayal of your position – exploiting the obvious weaknesses in the bank’s systems and the lack of proper supervision to which you should have been subject, lying to your seniors, falsifying documents, removing or avoiding protections the bank should have had … all over a long period of time … wholly motivated by greed … mesmerised by the luxury in which as a result of what you did David Mills let you wallow.”

The judge added that Scourfield had “sold his soul to Mills” for “sex, luxury trips, bling and swag”.

Addressing Mills, Beddoe said: “You are a thoroughly corrupt and devious man, adept at exploiting the weaknesses of others, particularly where that weakness is money, and adept too in getting others to do your dirty work for you. Standing in the shadows, you had Bancroft and his loyal lapdog, Cartwright, to get their hands dirty at your direction, and for your mutual financial advantage. In your case, compared to them, it has to be said, a staggering financial advantage.

Addressing Bancroft, Judge Beddoe said: “You were already clearly a thoroughly dishonest man as shown by what happened at Ritz (an aggravating feature in your case). You were Mills’s frontman and heavily engaged in the process of maintaining the hold both you and he had on Scourfield. You are clearly a bully, and with Mills you plundered Theros, Multi Sourcing Group and Remnant Media for fees and any useful assets you could get your hands on.”

Anthony Stansfeld, the police and crime commissioner for Thames Valley, also raised a critical point, highlighting the responsibilities of HBOS top management, one of whose roles is supposed to be ensuring systems are in place to stop such crime waves from happening. Stansfeld said: “A fraud of this size could have taken place either displays complicity or incompetence, a lack of corporate governance, complacency, and an absence of proper safeguards.”

The absence of anything resembling proper corporate governance at HBOS, including the complicity of auditors, regulators and politicians in allowing this dangerous deficiency to persist for the seven years, is something that will be further explored in The Politics of Financial Risk, Audit and Regulation: A Case Study of HBOS. This book, written by Dr Atul Shah, a senior lecturer in accountancy and finance at the University of Suffolk, is is to be published by Routledge later this year. I have written the foreward.

Stansfeld also highlighted the risk that white-collar fraud gets ignored because of the punitive cost of investigating and prosecuting it. He said that the case had taken more than six years to bring to court, had involved 151 police officers and staff and had cost more than £7 million, a sum that having to be borne by the homeowners of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. Stansfield said: “If Thames Valley Police had not taken on this case, no one else would have and the crime would not have been investigated. The principal perpetrators would have escaped with their reputations intact and with enormous wealth.”

Stansfeld suggested the cost of probes like Operation Hornet should be borne by central government, by the negligent or offending institution and by the negligent or offending institution’s auditors. In the case of the HBOS fraud, his proposal would see Lloyds Banking Group and KPMG sharing the £7m Operation Hornet tab. Stansfeld, a former Army officer who commanded army helicopters during the Falklands war, added: “There needs to be an agreed policy that if a major fraud is committed, and the Serious Fraud Office does not have the capacity to take it on, then the police force that investigates it is reimbursed by central government, or through a fine or costs imposed on the auditors, the bank and the offenders involved,” he said.

Speaking outside the court Paul Turner, without whom the trial would never have happened, said: “We are glad it has come to an end and they are going to prison. The bank knew about this since 2006 and has persecuted us when they knew we were telling the truth. It’s not over yet.”

Nikki Turner, who played a no less pivotal role in researching the crimes and bringing them to the attention of the authorities, added: “They defrauded us, denied for 10 years that the fraud had happened, ignored the debt from the fraud and tried to evict us 22 times in order to cover up the fraud. It’s a huge success for us that the trial has gone on.” She added: “The victims have gone through terrible things, they have gone through the loss of businesses and lost homes. Other people lost everything, including marriages broken up, because of this.”

Wearing her hat as founder and director of SME Alliance, which is campaigning to level the playing-field when small businesses are in disputes with their banks, and whose “no-one is above the law” slogan is a quote from Bank of England governor Mark Carney, Mrs Turner added: “What’s amazing is that that this fraud cost the shareholders of HBOS and subsequently Lloyds over £1bn but it isn’t mentioned anywhere in the accounts. That points to a need for far greater transparency and much improved corporate governance across the UK banking sector. Shareholders ought to be jumping up and down with rage that Lloyds allowed these crooks to effectively steal millions of pounds, and then kept them in the dark about it.”

Also standing outside court Joanne Dove, whose award-winning eco-nappy business Cotton Bottoms was wiped out by Scourfield, Mills and Bancroft, said: “We’ve served a prison sentence for 12 years since this happened and we have lived in penury. While [David Mills] has been waiting for trial he has lived a luxury life on all the assets that he has built up. A mother of five, Freer added: “I will never get the time back. That’s the sad thing. I will never get my children’s childhoods back to give them the things they would have had, had they not defrauded me.”

While it undoubtedly pleasing to see justice done and that at least some crooked bankers and their accomplices have been brought to book, the problems with British banking, clearly, go much, much deeper than this.

I suspect that the ‘Wild West’ of “turnaround consultants”, insolvency practitioners and banks’ “business support units” will come under much greater scrutiny and that legislation underpinning these areas will have to be tightened up. It’s worth noting that Thames Valley Police’s six-year ‘Operation Hornet’ investigation didn’t even look at the role played by insolvency practitioners from accountancy firms including PwC, KPMG, Vantis (now called FRP Advisory), Menzies Corporate Restructuring (now called Duff & Phelps), and Hurst Morrison Thomson (now HMT LLP), many of which seconded junior staff to work alongside Lynden Scourfield in 2003-07, in the scandal.

Insolvency practitioners from all these firms not only played a part in minimising the fallout by, for example, conducting whitewash “reviews” during 2006-07 but also by swiftly shutting down affected firms in what have been described as “skewed” administrations, which sometimes allowed key Quayside personnel to walk off with prized corporate assets, from April 2007 onwards. One wonders if the IPs’ failure to file “suspicious activity reports” to the Police, National Crime Agency or other relevant authorities was in any way related to the level of their fees.

The outcome of the HBOS Reading fraud case, together with the probability of future criminal trials related to HBOS and advisors, is said to be causing palpitations over at Royal Bank of Scotland, whose own ‘business support unit’, Global Restructuring Group, employed similar tactics to Bank of Scotland Corporate and Quayside, especially after the bank’s infamous “dash for cash ” programme was instituted on 9 October 2008 — albeit without the same degree of blatant criminality, explicit shabbiness, deviant sexual activity or nausea-inducing bling. If HBOS were the ‘cavaliers’ of insolvency abuse, RBS were very much the ’roundheads’.

Finally, after trying to evade its responsibilities towards the victims for more than seven years, Lloyds on Tuesday announced a “review” of all customer cases affected by Scourfield and Quayside’s crime wave. The bank said that customer cases would be “considered afresh in the light of all relevant evidence including new evidence that emerged during the trial… the group deeply regrets that the criminal actions have caused such distress for a number if HBOS customers”. Lloyds added that, in consultation with the Financial Conduct Authority, it would appoint “an independent third party” as part of the review with which it would agree scope methodology and individual case outcomes. The bank said redress would be provided “if appropriate”.

This was welcomed by Nils Pratley in the Guardian, who pointed out that there is “an unshakeable principle in takeovers is that you assume the responsibilities of the business you are buying, including nasties you didn’t know about.” However there is a degree of scepticism about the proposed review from former shareholders and directors of affected firms, largely because a similar review involving “independent third parties”, the FCA’s interest-rate swaps review, culminated in derisory compensation for many.

My hope for the future is that that banks and regulators will become quicker to address these sorts of internal scandals – by, among other things, punishing the wrongdoers and compensating the victims – as and when they occur rather than burying them for over a decade before the most obvious culprits are prosecuted.

As a coda, Court News UK issued a series of hard-hitting but amusing tweets just after the sentencing on Thursday 2 February; enjoy.

Thanks for posting this very interesting read. It would be nice to think that effective steps will be taken to prevent a recurrence of these sorts of crimes, but I fear that a Brexit Britain is likely to be preoccupied with other matters.

This seems like a classic case for a US-style class-action lawsuit. I cannot see Lloyds being in any way generous with any restitution. Also, how independent is a 3rd party when they must be being funded in their investigation by the guilty party?

That kind of fraud can only take place in companies where ‘social competence’ is highly valued. Social competence today is about covering up the misdeeds of colleagues, supervisors and even the whole business practice of the company.

Speaking out about possible suspected wrongdoings causes awkward moments – socially competent people don’t cause awkward moments so…

Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil – the bastardised modern interpretation of social competence.

The story also highlights the difficulty for business customers to switch banks. Banking for SMEs is a relationship business and even if the bank is the one who behaves badly then the customer is automatically is under suspicion and therefore unlikely to find a willing new lender/bank.

& I do believe that the story highlights yet another reason why banks needs to be smaller. A smaller bank could not afford not to have efficient controls in place and will also enforce those controls.

“Social competence” – is that the new euphemism for “yes man” or “flunkie”? I have never worked in a bank, but working for the government, I know the fastest way to the top is to be a “yes man” to one of the politically well-connected. Obviously, what they have is “social competence” – nice to finally know what the proper term for that behavior is! And all along we were just calling it “a$$-kissing”…

In the UK “Social competence” = Old Boys Network.

In the job-ads the eupehmism for yes-man is (as far as I can tell) someone with social competence.

If the ad has ‘we value personality’ (personal character or similar) then the message is: the job has already been filled but HR makes us place the ad so please apply. For you the benefit in applying is that the unemployment agency will be happy with your effort in applying for jobs but please have no expectation of getting the job…

The fastest way to the top in pretty much any firm is to be an arse kisser.

So basically these 3 guys pioneered this business practice, and RBS institutionalized and professionalized it? http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2016/10/rbs-looted-small-business-customers-deliberately-driving-thousands-in-bankruptcy-while-under-government-ownership.html

Its great to see there is still some proper journalism going on, well done for this.

In my interactions with former executives of the two main scottish banks I can discern no acknowledgement of this catastrophic failure of management. While they were probably just innocent cogs, the compartmentalisation is holding well.

It was all just a 100 billion worth of bad apples.

I thought that the Wells Fargo scandal was bad. This is just, ugh.

The banks probably turned a blind eye because that’s what many of them were effectively employing themselves as an MO ‘legitimately’.

As justifiably jittery, but still omnipotent lenders, particularly post 2008, in order to bolster their books and restore their increasingly battered balance sheets there were frequent examples of these institutional abuses simply because they could.

Those in possession of heavily mortgaged high value assets, mainly as part of a business, and at the end of their terms in search of new or additional funding were particularly vulnerable to their sharp practices.

This is a next step from white-collar crime; these are literal mafia tactics and people involved aren’t some professionals who broke one regulation or another, these are career criminals, pure and simple. I wonder how many of such activities go on undiscovered because perpetrators cover their tracks better.

Ian Fraser deserves recognition – a lot of recognition – for pursuing this story for ten years. Very few journalists would have done the same. The UK is a very small place and as soon as you get into the business world you learn to avoid stepping on toes.

I agree. Such tenaciousness deserves full recognition: Great Work, Mr. Fraser!

Thanks, Rich and JEHR!

As an ex-Brit who many years ago started his own business based in Colchester, Essex, I am utterly appalled at the revelations in this post. To be frank, they are one of the worst examples of greed and selfishness I have ever seen. Thankfully I was with Lloyds Bank and never required funding; my business generated a positive cash flow. But it would have been so easy to get sucked into such a mess for my instincts then were to trust all U.K. banks.

To cure yourself from the belief that these are the worst examples, I would recommend reading this article: http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2016/10/rbs-looted-small-business-customers-deliberately-driving-thousands-in-bankruptcy-while-under-government-ownership.html

Fascinating piece, and it’s nice to know that somewhere, someone out there, still knows how to put “investigative” into “reporting.”

Watching the shenanigans that the 1% and their cronies have been up to with near total impunity for the past two decades, how can anyone be astonished, much less mildly surprised, at the Brexit (and Trump) vote?

+100

As this sort of corruption becomes rife throughout the business sector, compared to say 40 years ago, it affects more and more people. And while the victims’ stories are ignored and their voices are silenced, they and their families and friends are fully aware of the injustice done to them. This is the reality that underlies breezy news stories about the economic “recovery”. Everyone who’s been kicked gets to vote — and there are a lot more kicked than kicking. Just give them the opportunity. They’ll kick back.

The problem is, like the failure of Barings, senior people are complicit in this fraud whether through malice or incompetence and yet none will be brought to book over it.

If you read the book “Confessions of an economic hit man” this model, albiet on a much bigger scale has been used by western govts to steal the assets of forgien countries for decades.

Hardly surprising nobody in govt wanted to do anything about these cases , and turned a blind eye. They were too busy trying to loot Iraq.

What an excellent bit of work Ian Fraser has done to expose the financial fraud that HBOS Directors allowed. This article is a truly magnificent example of investigative journalism. It should become a case study wherever the subject is studied; wherever aspiring journalists go for instruction. Thank you NC for another fine bit of information.

Thank you, R B Houghton !

Kudos Ian….

Sadly this is not just a banking problem, but enabled via the usual suspects welding wonky metaphysical prose…. how is it on one hand individual responsibility is preached from on high above, but, at the same time some display none…

disheveled…. might just be little old defective me, but it seems the more responsibility some have, the less subject they are – too – their – actions…. the larger social ramifications of that can’t bode well imo… looks outside window….