By Steve Roth, publisher of EvonomicsAsymptosis, Angry Bear, and Seeking Alpha. Follow him on Twitter at @asymptosis. Originally published at Evonomics

Households save money and lend it to businesses, who invest it in productive enterprises. That’s the economic story you’ve been hearing your whole life, right? Or at least since Econ 101. Saving funds investment. That core idea is embedded (and unquestioned) in modern macro: the Solow growth model, IS/LM, the lot.

Put aside that the basic bookkeeping of this idea — that personal saving creates “savings” that “fund” lending and investment — doesn’t make any sense. (It’s an error of composition; you have more savings if you save, but the economy doesn’t.) Let’s look at history: when households save more, is there more lending and (business) investment — either immediately or a few quarters/years down the road?

Mostly: no.

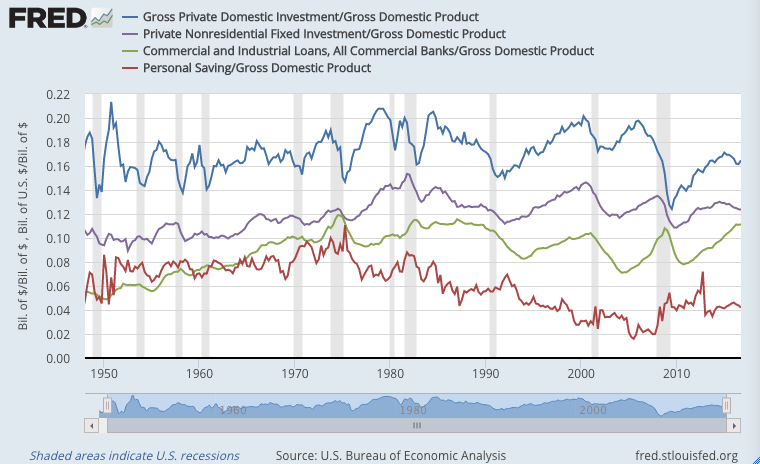

Here are some saving, lending, and investment measures for the U.S., post-war (starting Q1 1948), all divided by GDP to make them comparable:

The first thing to notice here: both lending and investment are vastly larger than household saving. They can’t be “funded” by that saving, or at least not much. (Think: bank lending and endogenous money.)

Otherwise, eyeballing this, it’s pretty much impossible to tell if these measures are correlated. When saving goes up or down, do lending and investment do likewise (concurrently, or some time later)? They’re all over the place. So let’s use software to look at correlations between them.

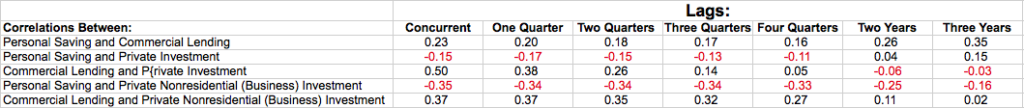

A correlation of 1.0 means the two measures move perfectly together — if X goes up, so does Y, by an equal amount. A correlation of -1 means they move perfectly in opposite directions — if X goes up, Y always goes down by an equal amount.

Of course, correlation doesn’t demonstrate causation. But lack of correlation, and especially negative correlation, does much to disprove causation. What kind of disproofs do we see here?

• Personal saving and commercial lending seem to be lightly correlated. The correlation declines over the course of a year, but then increases two or three years out. It’s an odd pattern, with a lot of possible causal stories that might explain it.

• Personal saving and private investment (including both residential and business investment) are very weakly correlated, and what correlation there is is mostly negative. More saving correlates with less investment.

• Commercial lending has medium-strong correlation with private investment in the short term, declining rapidly over time. This is not terribly surprising. But it has nothing to do with private saving.

• Perhaps the most telling result here: Personal saving has a significant and quite consistent negative correlation with business investment. Again: more saving, less investment. This directly contradicts what you learned in Econ 101.

• The last line — commercial lending versus business investment — is most interesting compared to line 3 (CommLending vs PrivInv). Changes in commercial lending seem to have their strongest short-term effects on residential investment, not business investment. But its effect on business investment seems more consistent and longer-term.

I’ll leave my gentle readers to ponder those only-somewhat stylized facts. Here’s the spreadsheet for any who want to explore further.

“The first thing to notice here: both lending and investment are vastly larger than household saving. They can’t be “funded” by that saving, or at least not much.”

Actually, that can easily be explained within the context of the textbook “savings capitalize loans for investment” thesis – it is more or less the rationale behind fractional reserve banking (FRB). Within the same framework, note that savings would only constrain lending if lending were near the leverage limit set by whatever (inverse) fraction applied to FRB system in question.

Similarly, the fact that increases in savings rate often correlate negatively with business investment can be explained by people putting more money away when the economy is looking rocky – same reason central bankers’ pleas to consumers to do their patriotic duty and help fight downturns by spending like there’s no tomorrow tend to fall on deaf ears.

This is not to say that the textbooks are correct – merely that many of the arguments put forth to ‘debunk’ the textbook explanation in fact do no such thing.

As the “Criticisms of textbook descriptions of the monetary system” section of the Wikipedia entry on FRB notes, the crucial shortcoming of the textbook description is that it fails to deal with reality that in most modern economies money for investment is endogenous rather than exogenous.

I’ve long been of the impression that even when they are doing their formal reserve requirement computations, the most important players in leverage booms such as led up to the 2008 crisis have a huge amount of leeway to play fast and loose with reserves – recall e.g. the GFC-era repeal of the FASB mark-to-market rules, all intended to allow mark-to-fantasy for ‘illiquid’ (polite euphemism for ‘toxic’). Given how things actually work, perhaps we should just use ‘fictional reserve banking’ as a descriptor for things – that way we give a nod to the theory while acknowledging the leverage-unconstrained reality.

“In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they’re different.” — Yogi Berra

…the rationale behind fractional reserve banking (FRB).

Every central bank in the World has gone on record that loans create deposits.

Fractional reserve banking is a misnomer, a Rube Goldberg style mathematical exercise that has no real relationship to how money is actually created in the banking system.

Yogi Berra did not say that. Computer scientist Jan L. A. van de Snepscheut (probably) did.

It seems that it might be good to investigate if savings and investment are both correlated to the stage of the business-cycle. If that correlation exists and is not controlled for then the conclusions of the above report might not be as conclusive as hoped for.

If you look at the shaded areas in the graph, you see that investments (non-residential and total) drop dramatically during recessions while lending drops with a short lag after the recession. Savings typically rise during the recession and usually drop during the expansionary phases. This seems to reinforce the conclusions of the above report.

Gah — should read “illiquid … *assets*” in my above comment.

Negative correlation between saving and investment would make sense for Keynesian reasons if more intended savings means less consumption driving a fall in investment because of the lack of customers

Spot on.

But modern economics thought is an intense contorsive dance to eliminate consumption and aggregate demand from all equations.

‘The first thing to notice here: both lending and investment are vastly larger than household saving.‘

Duh, WTF: corporations save too. So do governments, in the rare event that they run surpluses.

Not a good idea to criticize Econ 101 without having read the freakin’ textbook.

I was gonna post a question about that. How can S = I when the graph shows them being so UN-equal?

This data is restricted to the USA alone – which is problematic for the following reasons:

1) the USD is the reserve currency of the empire – which has gone to war to preserve its status as the currency of international trade. It cannot be considered in isolation as if the US economy was a stand-alone national economy – it clearly is not.

2) International actors have massive USD positions – and this is ignored in the article’s analysis.

3) culturally, Americans are not savers – rather risk-taking borrowers – I’d like to see this analysis applied to an economy where saving is more culturally normal – Italy, or China, where savings rates often exceed 30%.

4) The USA is unique in that the central bank is privately-owned and run for the benefit of the banks that own it. This is a massive distortion in the money system.

5) Where banks can borrow at zero interest from the central bank, and savers earn maybe 0.25% on their savings, where is the incentive to banks to solicit savers, or for savers to save?

Perhaps the reason the theory does not apply is that bankers have the power to run their affairs without needing the savings of the rubes.

Exactly. It’s be interesting to see how the saving/lending/growth picture worked out if the analysis was limited to credit unions and local commercial banks. Imagine a middle class economy of 100,000 families where 10% of income is deposited as savings in local banks, average family income of $50,000 a year. $5000 x 100,000 = $500 million. Banks have to loan the money out at interest rates greater than the rate paid to savings account holders to earn a profit. Their market is people wishing to buy homes, automobiles, expand their small businesses, etc. So the banks will actively encourage people to buy their money and this will tend to spur investment and economic growth, it’s a fairly simple argument.

You have to make a very convuleted argument to claim that this isn’t true; but if you can make that argument, it tends to justify credit bubbles, mergers of commercial and investment banking, the federal reserve printing mass amounts of money without fear of inflation since foreign countries are buying the petrodollar as reserve currency, etc. – the net effect of which is that wealth evaporates from the middle class into the pockets of the uber-wealthy.

Seems obvious. The whole attraction to a savings account or CD is that I get interest on my money. Interest earned on my account derives from the interest on loan repayments, a fraction of which go into accounts and the rest stays with the financial company/institution. “Savings cause lending” is putting the cart before the horse. The checking and savings accounts are really just a way to “get you in the door” in the hopes that down the line you’ll do more business with the bank, in the form of taking out a home/auto/business loan.

I never completely understood the savings = investment thing either. Let’s say I got a 10 bagger and ended up with $1000. Let’s say I put it in a checking account. That’s savings but how is it investment?

Then let’s say I go out and buy a $300 video game “Redneck Nation” where you can be a liberull and drive around and run over unemployed meth-addict rednecks with your car or shoot them as they run away. Each time you hit one the sound effects are awesome. If you hit 10 in 5 minutes it plays Lnnyrd Skynnard’s Sweet Home Alabama.

Let’s say the game developer makes yuuuuuge amounts of money and puts it in a cash account invested in govermint securities. That’s not investment either but it’s savings.

Only one minor nit. Correlation is a measure of linearity. The slope of the implied line doesn’t have to be 45 degrees. In other words, consider the x,y pairs 1,3, 2,6, 3,9, 4,12, 5,15. If you ran a correlation it would be “1”. Linearity, and therefor correlation of 1 (or -1), can exist even if one variable changes in magnitude more than the other — provided the relationship between the two variable is linear, i.e. of the form y=ax + b; where b is a constant and can be zero.

If you buy a financial product it’s “investment” in the financial and not physical sense. S is supposed to = I for physical investment. When you save money it isn’t invested in the sense that the bank lends an equal amount of money to somebody. (Banks do not lend out the deposits or reserves.)

S = I means the total savings in the economy equals the total investment. The two are connected via inventories, increases in inventories count as investment.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Savings_identity

afaik you can put it another way, the money people in the economy do not spend on consumption is saved. And the spending which is not consumption spending is investment spending. Therefore S always equals I

Gosh, could it be that if people are “saving” they are not “buying” so much so demand is lower, which means business has little reason to expand? I think economists devising little simplistic statements such as the one offered are just one more reason to not trust economists. They do not seem to know what they are doing … or they do and it is serving a master other than us.

That was what Keynes thought. Savings and investment remain equal at all times, but they stay the same via the level of output changing to keep them the same.

Banks create the money they lend out of nothing, it’s called fractional reserve banking.

After years of lobbying the reserves they need are almost nothing, a fee on a mortgage can contain the required reserve by itself.

In the UK the banks held £1.25 in reserves for every £100 lent out in 2008.

Money is created by loans and destroyed by the repayments.

From the BoE:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

Savings did play a role with higher reserve ratios but today they are almost irrelevant.

When economists get the hang of how money works they will know why austerity doesn’t work and be able to see events like 2008 coming.

http://www.whichwayhome.com/skin/frontend/default/wwgcomcatalogarticles/images/articles/whichwayhomes/US-money-supply.jpg

M3 is going vertical before 2008.

Money = debt and a credit bubble is blowing up.

2008 bang.

The banks do not create money, we do! :)

If John Doe goes into a bank and signs a bit of paper that says he owes the bank10000 dollars, that very act creates 10000 dollars. John Doe has just created 10000 dollars out of thin air, by the fact that he pledges his working capability over the next few years. The problem with these John Doe money is getting it accepted, as Hyman Minsky rightly said.

So the bank acts as a risk assessing agency and as a risk taker and converts the John Doe money to US Dollars money, and receives interest for its risk taking. The John Doe pledge for 10000 dollars becomes a bank asset, and John Doe gets 10k USD in his bank account. Loans create Deposits. But before that the people create the money by assuming debt.

In my opinion, MMT starts one step too high up. To fully understand what is happening, we need to go one step lower, to the end customer, not to start with the bank.

A good paper on the “Hierarchy of money” by Stephanie Bell saying the same thing in much better style and detail: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp/231.pdf

That is another way of looking at it and the basis of double entry book keeping.

The bank can claim the asset if the borrower defaults, which is the whole idea.

Banks do create money out of nothing but it equates to you borrowing your own money from the future and paying the interest for this service.

The bank creates the money out of nothing, which is your own money from the future.

You pay it back plus the interest for the service rendered.

If you default the bank repossesses the asset to pay off the debt.

It all works well if banks lend prudently, but they don’t.

Loads of new money/debt comes into being before 2008 (M3 going vertical).

It is a huge asset bubble, when the bubble bursts people can’t repay their debt and the asset has fallen sharply in price so the bank can’t recoup the money to pay off the debt.

The system breaks – The Minsky Moment

Today’s record global debt is our own money borrowed from the future.

The future is massively impoverished before we get there.

Basic example

You buy the house with the money the bank lends you now.

In the future you pay that money back plus the interest.

The bank creates the money out of nothing for you to buy the house now.

You pay it back plus interest in the future.

It is moving your money from the future to the present.

The banks do not create money, we do! :)

That’s right. The necessary condition for money to be created through the banking system is for willing and able borrowers to walk through the doors and take out loans.

Banks are always pushing on a string.

Minor quibble. MMT has very little to say about banking other than money created through the system nets to zero, thus adds no net financial assets to the non-government. MMT focuses on the flow of funds between the government and non-government, exogenous money, ie net financial assets.

I couldn’t access the link.

I assume MMT is in the link.

“…it’s called fractional reserve banking.”

No it’s not. There is no such thing as fractional reserve banking.

Every central bank in the World agrees…loans create deposits.

Fractional reserve banking implies the opposite.

A link to one central bank paper confirming this:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasearticlemoney.aspx

“Every central bank in the World agrees…loans create deposits”

No one told the mainstream economists.

Probably quibbling about terminology.

I may be using the term fractional reserve banking incorrectly.

I have used it just to mean there is supposed to be a fraction as a reserve though in some cases I think this is now actually zero.

The mechanisms above are OK.

Fractional Reserve Banking is based on this kind of ‘arithmetic’…

The big problem with all this is the fact that banks are never reserve-constrained. A bank can always make a loan to a qualified borrower that walks through it’s doors and acquire the necessary reserves after-the-fact, either from another bank in the system with excess reserves or through the Fed discount window (albeit at a higher rate). It wouldn’t matter if the reserve requirement was 100%. The bank could always make the loan ( and make a profit, which leads to higher reserves).

So the fractional-reserve story above becomes moot, and has nothing to do with the actual process, while fueling the (false) notion that banks lend out deposits.

Which leads to the false “loanable funds theory” on which much of neoclassical economics is based. Paul Krugman subscribes to this so-called ‘theory’. It is this theory that underpins the arguments that ‘we are going bankrupt’ or ‘we can’t afford’ to do this or that. Belief in this theory is the the main reason we can’t have nice things.

This is why any reference to a so-called ‘fractional-reserve banking’ model must be exorcised from any discussion of economics or monetary systems.

Which is what MMT is working to do. MMT is a reality-based view of economics. We measure economic output in terms of GDP, which is a flow of funds. MMT is based on an accounting view of the flow of funds and a working knowledge of actual banking operations as opposed to stylized descriptions like fractional reserve banking.

[1] Banks don’t lend out deposits. Every penny of a loan is created from nothing. Your money (deposits) remains in your account and is always accessible by you.