Steve Keen is Professor of Economics and Head of the School of Economics, Politics and History at Kingston University London, author of Debunking Economics, and the developer of Minsky open source system dynamics modeling program. Originally published at Evonomics.

Excerpted from Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? by Steve Keen, Polity, Inc. All rights reserve, 2017.

Since 1976, Robert Lucas—he of the confidence that the “problem of depression prevention has been solved”—has dominated the development of mainstream macroeconomics with the proposition that good macroeconomic theory could only be developed from microeconomic foundations. Arguing that “the structure of an econometric model consists of optimal decision rules of economic agents” (Lucas, 1976, p. 13), Lucas insisted that to be valid, a macroeconomic model had to be derived from the microeconomic theory of the behaviour of utility-maximizing consumers and profit-maximizing firms.

In fact, Lucas’s methodological precept—that macro level phenomena can and in fact must be derived from micro-level foundations—had been invalidated before he stated it. As long ago as 1953 (Gorman, 1953), mathematical economists posed the question of whether what microeconomic theory predicted about the behaviour of an isolated consumer applied at the level of the market. They concluded, reluctantly, that it did not:

market demand functions need not satisfy in any way the classical restrictions which characterize consumer demand functions… The importance of the above results is clear: strong restrictions are needed in order to justify the hypothesis that a market demand function has the characteristics of a consumer demand function. Only in special cases can an economy be expected to act as an ‘idealized consumer’. The utility hypothesis tells us nothing about market demand unless it is augmented by additional requirements.’ (Shafer and Sonnenschein, 1993, p. 671-72)

What they showed was that if you took two or more consumers with different tastes and different income sources, consuming two or more goods whose relative consumption levels changed as incomes rose (because some goods are luxuries and others are necessities), then the resulting market demand curves could have almost any shape at all. They didn’t have to slope downwards, as economics textbooks asserted they did.

This doesn’t mean that demand for an actual commodity in an actual economy will fall if its price falls, rather than rise. It means instead that this empirical regularity must be due to features that the model of a single consumer’s behaviour omits. The obvious candidate for the key missing feature is the distribution of income between consumers, which will change when prices change.

The reason that aggregating individual downward sloping demand curve results in a market demand curve that can have any shape at all is simple to understand, but—for those raised in the mainstream tradition—very difficult to accept. The individual demand curve is derived by assuming that relative prices can change without affecting the consumer’s income. This assumption can’t be made when you consider all of society—which you must do when aggregating individual demand to derive a market demand curve—because changing relative prices will change relative incomes as well.

Since changes in relative prices change the distribution of income, and therefore the distribution of demand between different markets, demand for a good may fall when its price falls, because the price fall reduces the income of its customers more than the lower relative price boosts demand (I give a simple illustration of this in Keen, 2011 on pages 51-53).

The sensible reaction to this discovery is that individual demand functions can be grouped only if changing relative prices won’t substantially change income distribution within the group. This is valid if you aggregate all wage earners into a group called “Workers”, all profit earners into a group called “Capitalists”, and all rent earners into a group called “Bankers”—or in other words, if you start your analysis from the level of social classes. Alan Kirman proposed such a response almost 3 decades ago:

If we are to progress further we may well be forced to theories in terms of groups who have collectively coherent behavior. Thus demand and expenditure functions if they are to be set against reality must be defined at some reasonably high level of aggregation. The idea that we should start at the level of the isolated individual is one which we may well have to abandon. (Kirman, 1989, p. 138)

Unfortunately, the reaction of the mainstream was less enlightened: rather than accepting this discovery, they looked for conditions under which it could be ignored. These conditions are absurd—they amount to assuming that all individuals and all commodities are identical. But the desire to maintain the mainstream methodology of constructing macro-level models by simply extrapolating from individual level models won out over realism.

The first economist to derive this result, William Gorman, argued that it was “intuitively reasonable” to make what is in fact an absurd assumption that changing the distribution of income does not alter consumption:

The necessary and sufficient condition quoted above is intuitively reasonable. It says, in effect, that an extra unit of purchasing power should be spent in the same way no matter to whom it is given. (Gorman, 1953, pp. 63-64. Emphasis added)

Paul Samuelson, who arguably did more to create Neoclassical economics than any other 20th century economist, conceded that unrelated individual demand curves could not be aggregated to yield market demand curves that behaved like individual ones. But he then asserted that a “family ordinal social welfare function” could be derived “since blood is thicker than water”: family members could be assumed to redistribute income between each other “so as to keep the ‘marginal social significance of every dollar’ equal” (Samuelson, 1956, pp. 10-11. Emphasis added). He then blithely extended this vision of a happy family to the whole of society:

“The same argument will apply to all of society if optimal reallocations of income can be assumed to keep the ethical worth of each person’s marginal dollar equal” (Samuelson, 1956, p. 21. Emphasis added).

The textbooks from which mainstream economists learn their craft shielded students from the absurdity of these responses, and thus set them up to unconsciously make inane rationalisations themselves when they later constructed what they believed were microeconomically sound models of macroeconomics, based on the fiction of “a representative consumer”. Hal Varian’s advanced mainstream text Microeconomic Analysis (first published in 1978) reassured Masters and PhD students that this procedure was valid:

“it is sometimes convenient to think of the aggregate demand as the demand of some ‘representative consumer’… The conditions under which this can be done are rather stringent, but a discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this book…” (Varian, 1984, p. 268)

and portrayed Gorman’s intuitively ridiculous rationalisation as reasonable:

Suppose that all individual consumers’ indirect utility functions take the Gorman form … [where] … the marginal propensity to consume good j is independent of the level of income of any consumer and also constant across consumers … This demand function can in fact be generated by a representative consumer. (Varian, 1992, pp. 153-154. Emphasis added. Curiously the innocuous word “generated” in this edition replaced the more loaded word “rationalized” in the 1984 edition)

It’s then little wonder that, decades later, macroeconomic models, painstakingly derived from microeconomic foundations—in the false belief that it was legitimate to scale the individual up to the level of society, and thus to ignore the distribution of income—failed to foresee the biggest economic event since the Great Depression.

So macroeconomics cannot be derived from microeconomics. But this does not mean that “The pursuit of a widely accepted analytical macroeconomic core, in which to locate discussions and extensions, may be a pipe dream”, as Blanchard put it. There is a way to derive macroeconomic models by starting from foundations that all economists must agree upon. But to actually do this, economists have to embrace a concept that to date the mainstream has avoided: complexity.

The discovery that higher order phenomena cannot be directly extrapolated from lower order systems is a commonplace conclusion in genuine sciences today: it’s known as the “emergence” issue in complex systems (Nicolis and Prigogine, 1971, Ramos-Martin, 2003). The dominant characteristics of a complex system come from the interactions between its entities, rather than from the properties of a single entity considered in isolation.

My favourite instance of it is the behaviour of water. If one could, and in fact, one had to derive macroscopic behaviour from microscopic principles, then weather forecasters would have to derive the myriad properties of the weather from the characteristics of a single molecule of H2O. This would entail showing how, under appropriate conditions, a “water molecule” could become an “ice molecule”, a “steam molecule”, or—my personal favourite—a “snowflake molecule”. In fact, the wonderful properties of water occur, not because of the properties of individual H2O molecules themselves, but because of interactions between lots of (identical) H2O molecules.

The fallacy in the belief that higher level phenomena (like macroeconomics) had to be, or even could be, derived from lower level phenomena (like microeconomics) was pointed out clearly in 1972—again, before Lucas wrote—by the Physics Nobel Laureate Philip Anderson:

The main fallacy in this kind of thinking is that the reductionist hypothesis does not by any means imply a “constructionist” one: The ability to reduce everything to simple fundamental laws does not imply the ability to start from those laws and reconstruct the universe. (Anderson, 1972, p. 393. Emphasis added)

He specifically rejected the approach of extrapolating from the “micro” to the “macro” within physics. If this rejection applies to the behaviour of fundamental particles, how much more so does it apply to the behaviour of people?:

The behavior of large and complex aggregates of elementary particles, it turns out, is not to be understood in terms of a simple extrapolation of the properties of a few particles. Instead, at each level of complexity entirely new properties appear, and the understanding of the new behaviors requires research which I think is as fundamental in its nature as any other. (Anderson, 1972 , p. 393)

Anderson was willing to entertain that there was a hierarchy to science, so that:

one may array the sciences roughly linearly in a hierarchy, according to the idea: “The elementary entities of science X obey the laws of science Y”

Table 1: Anderson’s hierarchical ranking of sciences (adapted from Anderson 1972, p. 393)

| X | Y |

| Solid state or many-body physics | Elementary particle physics |

| Chemistry | Many-body physics |

| Molecular biology | Chemistry |

| Cell biology | Molecular biology |

| … | … |

| Psychology | Physiology |

| Social sciences | Psychology |

But he rejected the idea that any science in the X column could simply be treated as the applied version of the relevant science in the Y column:

But this hierarchy does not imply that science X is “just applied Y”. At each stage entirely new laws, concepts, and generalizations are necessary, requiring inspiration and creativity to just as great a degree as in the previous one. Psychology is not applied biology, nor is biology applied chemistry. (Anderson, 1972 , p. 393)

Nor is macroeconomics applied microeconomics. Mainstream economists have accidentally proven Anderson right by their attempt to reduce macroeconomics to applied microeconomics, firstly by proving it was impossible, and secondly by ignoring this proof, and consequently developing macroeconomic models that blindsided economists to the biggest economic event of the last seventy years.

The impossibility of taking a “constructionist” approach to macroeconomics, as Anderson described it, means that if we are to derive a decent macroeconomics, we have to start at the level of the macroeconomy itself. This is the approach of complex systems theorists: to work from the structure of the system they are analysing, since this structure, properly laid out, will contain the interactions between the system’s entities that give it its dominant characteristics.

This was how the first complex systems models of physical phenomena were derived: the so-called “many body problem” in astrophysics, and the problem of turbulence in fluid flow.

Newton’s equation for gravitational attraction explained how a predictable elliptical orbit results from the gravitational attraction of the Sun and a single planet, but it could not be generalised to explain the dynamics of the multi-planet system in which we actually live. The great French mathematician Henri Poincare discovered in 1899 that the orbits would be what we now call “chaotic”: even with a set of equations to describe their motion, accurate prediction of their future motion would require infinite precision of measurement of their positions and velocities today. As astrophysicist Scott Tremaine put it, since infinite accuracy of measurement is impossible, then “for practical purposes the positions of the planets are unpredictable further than about a hundred million years in the future”:

As an example, shifting your pencil from one side of your desk to the other today could change the gravitational forces on Jupiter enough to shift its position from one side of the Sun to the other a billion years from now. The unpredictability of the solar system over very long times is of course ironic since this was the prototypical system that inspired Laplacian determinism. (Tremaine, 2011)

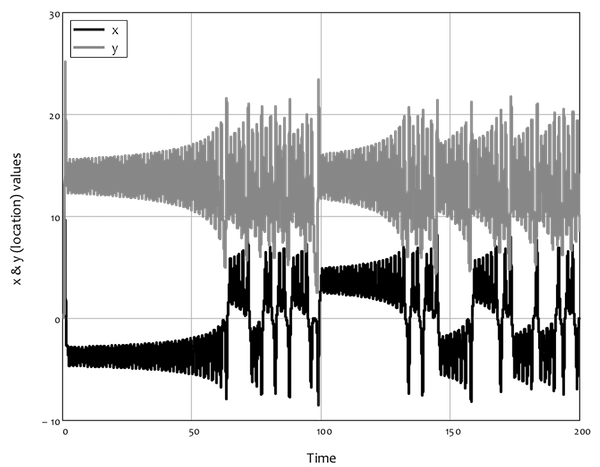

This unpredictable nature of complex systems led to the original description of the field as “Chaos Theory”, because in place of the regular cyclical patterns of harmonic systems there appeared to be no pattern at all in complex ones. A good illustration of this is Figure 1, which plots the superficially chaotic behaviour over time of two of the three variables in the complex systems model of the weather developed by Edward Lorenz in 1963 (Lorenz, 1963).

Figure 1: The apparent chaos in Lorenz’s weather model

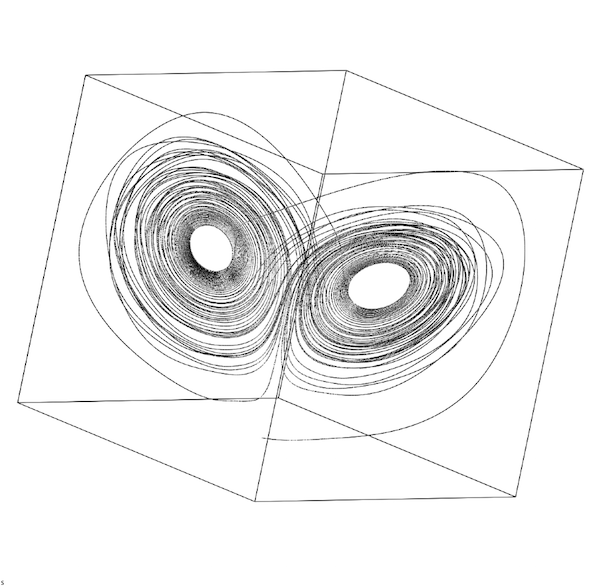

However, long term unpredictability means neither a total lack of predictability, nor a lack of structure. You almost surely know of the phrase “the butterfly effect”: the saying that a butterfly flapping or not flapping its wings in Brazil can make the difference between the occurrence or not of a hurricane in China. The butterfly metaphor was inspired by plotting the three variables in Lorenz’s model against each other in a “3D” diagram. The apparently chaotic behaviour of the x and z variables in the “2D” plot of Figure 2 gives way to the beautiful “wings of a butterfly” pattern shown in Figure 2 when all three dimensions of the model are plotted against each other.

Figure 2: Lorenz’s “Butterfly” weather model—the same data as in Figure 1 in 3 dimensions

The saying does not mean that butterflies cause hurricanes, but rather that imperceptible differences in initial conditions can make it essentially impossible to predict the path of complex systems like the weather after a relatively short period of time. Though this eliminates the capacity to make truly long term weather forecasts, the capacity to forecast for a finite but still significant period of time is the basis of the success of modern meteorology.

Lorenz developed his model because he was dissatisfied with the linear models that were used at the time to make weather forecasts, when meteorologists knew that the key phenomena in weather involved key variables—such as the temperature and density of a gas—interacting with each other in non-additive ways. Meteorologists already had nonlinear equations for fluid flow, but these were too complicated to simulate on computers in Lorenz’s day. So he produced a drastically simplified model of fluid flow with just 3 equations and 3 parameters (constants)—and yet this extremely simple model developed extremely complex cycles which captured the essence of the instability in the weather itself.

Lorenz’s very simple model generated sustained cycles because, for realistic parameter values, its three equilibria were all unstable. Rather than dynamics involving a disturbance followed by a return to equilibrium, as happens with stable linear models, the dynamics involved the system being far from equilibrium at all times. To apply Lorenz’s insight, meteorologists had to abandon their linear, equilibrium models—which they willingly did—and develop nonlinear ones which could be simulated on computers. This has led, over the last half century, to far more accurate weather forecasting than was possible with linear models.

The failure of economics to develop anything like the same capacity is partly because the economy is far less predictable than the weather, given human agency, as Hayekian economists justifiably argue. But it is also due to the insistence of mainstream economists on the false modelling strategies of deriving macroeconomics by extrapolation from microeconomics, and of assuming that the economy is a stable system that always returns to equilibrium after a disturbance.

Abandoning these false modelling procedures does not lead, as Blanchard fears, to an inability to develop macroeconomic models from a “widely accepted analytical macroeconomic core”. Neoclassical macroeconomists have tried to derive macroeconomics from the wrong end—that of the individual rather than the economy—and have done so in a way that glossed over the aggregation problems that entails by pretending that an isolated individual can be scaled up to the aggregate level. It is certainly sounder—and may well be easier—to proceed in the reverse direction, by starting from aggregate statements that are true by definition, and then by disaggregating those when more detail is required. In other words, a “core” exists in the very definitions of macroeconomics.

Using these definitions, it is possible to develop, from first principles that no macroeconomist can dispute, a model that does four things that no DSGE model can do: it generates endogenous cycles; it reproduces the tendency to crisis that Minsky argued was endemic to capitalism; it explains the growth of inequality over the last 50 years; and it implies that the crisis will be preceded, as it indeed was, by a “Great Moderation” in employment and inflation.

The three core definitions from which a rudimentary macro-founded macroeconomic model can be derived are the employment rate (the ratio of those with a job to total population, as an indicator of both the level of economic activity and the bargaining power of workers), the wages share of output (the ratio of wages to GDP, as an indicator of the distribution of income), and, as Minsky insisted, the private debt to GDP ratio.

When put in dynamic form, these definitions lead to not merely “intuitively reasonable” statements, but statements that are true by definition:

- The employment rate (the percentage of the population that has a job) will rise if the rate of economic growth (in percent per year) exceeds the sum of population growth and labour productivity growth;

- The percentage share of wages in GDP will rise if wage demands exceed the growth in labour productivity; and

- The debt to GDP ratio will rise if private debt grows faster than GDP.

These are simply truisms. To turn them into an economic model, we have to postulate some relationships between the key entities in the system: between employment and wages, between profit and investment, and between debt, profits and investment.

Here an insight from complex systems analysis is extremely important: a simple model can explain most of the behaviour of a complex system, because most of its complexity come from the fact that its components interact—and not from the well-specified behaviour of the individual components themselves (Goldenfeld and Kadanoff, 1999). So the simplest possible relationships may still reveal the core properties of the dynamic system—which in this case is the economy itself.

In this instance, the simplest possible relationships are:

- Output is a multiple of the installed capital stock;

- Employment is a multiple of output;

- The rate of change of the wage is a linear function of the employment rate;

- Investment is a linear function of the rate of profit;

- Debt finances investment in excess of profits; and

- Population and labour productivity grow at constant rates.

The resulting model is far less complicated than even a plain vanilla DSGE model: it has just 3 variables, 9 parameters, and no random terms. It omits many obvious features of the real world, from government and bankruptcy provisions at one extreme to Ponzi lending to households by the banking sector at the other. As such, there are many features of the real world that cannot be captured without extending its simple foundations.

However, even at this simple level, its behaviour is far more complex than even the most advanced DSGE model, for at least three reasons. Firstly, the relationships between variables in this model aren’t constrained to be simply additive, as they are in the vast majority of DSGE models: changes in one variable can therefore compound changes in another, leading to changes in trends that a linear DSGE model cannot capture. Secondly, non-equilibrium behaviour isn’t ruled out by assumption, as in DSGE models: the entire range of outcomes that can happen is considered, and not just those that are either compatible with or lead towards equilibrium. Thirdly, the finance sector, which is ignored in DSGE models (or at best treated merely as a source of “frictions” that slow down the convergence to equilibrium), is included in a simple but fundamental way in this model, by the empirically confirmed assumption that investment in excess of profits is debt-financed (Fama and French, 1999a, p. 1954).

The model generates two feasible outcomes, depending on how willing capitalists are to invest. A lower level of willingness leads to equilibrium. A higher level leads to crisis.

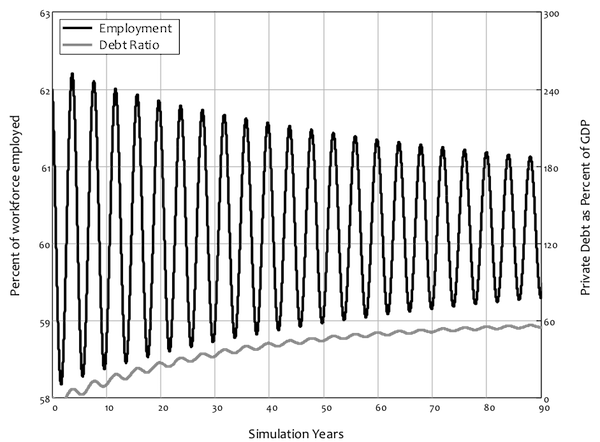

With a low propensity to invest, the system stabilises: the debt ratio rises from zero to a constant level, while cycles in the employment rate and wages share gradually converge on equilibrium values. This process is shown in Figure 3, which plots the employment rate and the debt ratio.

Figure 3: Equilibrium with less optimistic capitalists

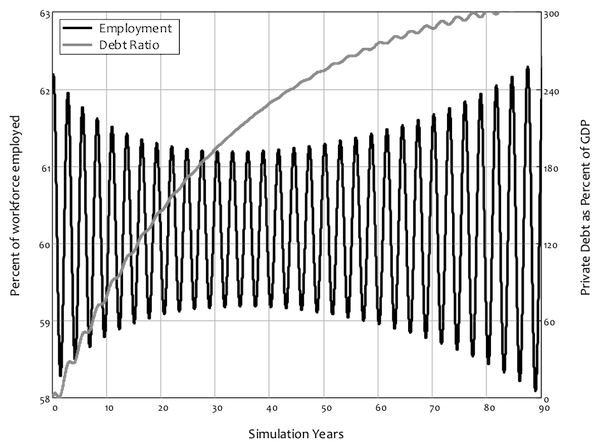

With a higher propensity to invest comes the debt-driven crisis that Minsky predicted, and which we experienced in 2008. However, something that Minsky did not predict, but which did happen in the real world, also occurs in this model: the crisis is preceded by a period of apparent economic tranquillity that superficially looks the same as the transition to equilibrium in the good outcome. Before the crisis begins, there is a period of diminishing volatility in unemployment, as shown in Figure 4: the cycles in employment (and wages share) diminish, and at a faster rate than the convergence to equilibrium in the good outcome shown in Figure 3.

But then the cycles start to rise again: apparent moderation gives way to increased volatility, and ultimately a complete collapse of the model, as the employment rate and wages share of output collapse to zero and the debt to GDP ratio rises to infinity. This model, derived simply from the incontestable foundations of macroeconomic definitions, implies that the “Great Moderation”, far from being a sign of good economic management as mainstream economists interpreted it (Blanchard et al., 2010, p. 3), was actually a warning of an approaching crisis.

Figure 4: Crisis with more optimistic capitalists

The difference between the good and bad outcomes is the factor Minsky insisted was crucial to understanding capitalism, but which is absent from mainstream DSGE models: the level of private debt. It stabilizes at a low level in the good outcome, but reaches a high level and does not stabilize in the bad outcome.

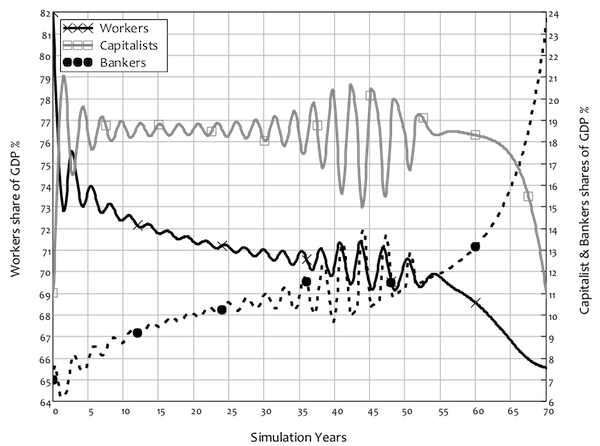

The model produces another prediction which has also become an empirical given: rising inequality. Workers’ share of GDP falls as the debt ratio rises, even though in this simple model, workers do no borrowing at all. If the debt ratio stabilises, then inequality stabilises too, as income shares reach positive equilibrium values. But if the debt ratio continues rising—as it does with a higher propensity to invest—then inequality keeps rising as well. Rising inequality is therefore not merely a “bad thing” in this model: it is also a prelude to a crisis.

The dynamics of rising inequality are more obvious in the next stage in the model’s development, which introduces prices and variable nominal interest rates. As debt rises over a number of cycles, a rising share going to bankers is offset by a smaller share going to workers, so that the capitalists share fluctuates but remains relatively constant over time. However, as wages and inflation are driven down, the compounding of debt ultimately overwhelms falling wages, and profit share collapses. Before this crisis ensues, the rising amount going to bankers in debt service is precisely offset by the declining share going to workers, so that profit share becomes effectively constant and the world appears utterly tranquil to capitalists—just before the system fails.

Figure 5: Rising inequality caused by rising debt

I built a version of this model in 1992, long before the “Great Moderation” was apparent. I had expected the model to generate a crisis, since I was attempting to model Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis. But the moderation before the crisis was such a striking and totally unexpected phenomenon that I finished my paper by focusing on it, with what I thought was a nice rhetorical flourish:

From the perspective of economic theory and policy, this vision of a capitalist economy with finance requires us to go beyond that habit of mind which Keynes described so well, the excessive reliance on the (stable) recent past as a guide to the future. The chaotic dynamics explored in this paper should warn us against accepting a period of relative tranquility in a capitalist economy as anything other than a lull before the storm. (Keen, 1995b, p. 634. Emphasis added)

Though my model did predict that these phenomena of declining cycles in employment and inflation and rising inequality would precede a crisis if one were to occur, I didn’t expect my rhetorical flourish to manifest itself in actual economic data. There were, I thought, too many differences between my simple, private-sector-only model and the complicated (as well as complex) real world for this to happen.

But it did.

I have been following Steve Keen’s work for a couple of years.

I very much hope he will be able to finalize his model soon and feed it with actual data, so that we can (1) validate its behaviour retrospectively and (2) get some short- to medium-term forecasts — which will be then checked with actual events.

Been following Dr Keen since he was still in Australia. While I like his dynamic methods, I can find no reason to think that economics to a large extent, doesn’t flow from the limits of human psychology and physiology. How do you dynamically model corruption and irrationality?

Or dominance drives, or the pleasure principle and its derivatives from credentialed actors, https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/pleasure-principle/, or sadomasochism, or, or, or… Not just the “limits of psychology and physiology,” but the EXTENT and terrain of those frames.

I recall paging through one early popular book on chaos theory and finding that diagramming of three-dimensional ordering, the “butterfly model” pictured above, and wondering about some kind of semiotic connection to the Global Unconscious since it sure looks like the mathematical symbol for “infinity,” which I recall is represented in a variety of cultural appearances, http://www.ancient-symbols.com/symbols-directory/infinity.html

The 2 loops in the 3D version of the data (fig. 2) are known as ‘strange attractors’, this particular system has 2 of them. The attractors are also visible in fig. 1 in the 2 levels about which the X variable oscillates, appearing to slowly stabilize to the mid point of the oscillation before suddenly switching to the other attractor.

If you center a metal pendulum over a triangle of magnets you will also get a chaotic system, but there will be 3 attractors.. and 3 loops in the graph.

It’s not that each more complex level doesn’t flow from the previous, but that each level is sufficiently more complex than the previous that (1) we can’t predict the higher-level outcome from lower-level units and/or (2) the higher-level outcome is too complex to comprehend in terms of lower-level units, so we must think in higher-level units and terms.

To extend Dr. Keen’s analogy with water, we can imagine a model for a piston of liquid water whose volume we expand. We might assume that every unit of marginal volume we add to the piston by expansion is evenly distributed among the molecules. This leads us to erroneously believe that the water will uniformly expand and all water molecules will be equidistant in space. Our assumption is wrong — the water molecules instead divide into a liquid phase and a gas phase. Every water molecule does not get the marginal volume equally.

Of course today we can simulate water molecules on a computer and see the emergent phases of liquid and gas, and furthermore it is obvious to us that water molecules exist in different phases of matter. But to some, the division of individuals between workers, capitalists, and bankers (for example) is just as obvious, and apparently these DSGE models by design exclude this possibility, in the same way we didn’t allow separate liquid and gas phases to exist.

You understand, that for the purposes of analysis (whatever may actually happen) … the sum may be greater than the parts. Emergent phenomena are only obvious after the fact. You are ready to leave the monastery … since you have demonstrated the ability to snatch a pebble out of the hand of Adam Smith.

Thanks for the water!

I think the point of avoiding model where a collection of interrelated micromodels is extrapolated to a macro model is that you don’t have to model the motivators of individual humans in the system. It’s analogous (as was pointed out above) to weather models. There is no attempt to follow individual molecules of air or water vapor which are controlled by forces that are not even mentioned in the weather model.

This is a great post.

The problem is that at a microeconomic level, it is impossible to see the broader structural conditions that shape an economy. The most important one in our era (since the 70’s) is the crisis of overproduction/under-utilization of capacity in the global manufacturing sector that has caused the rate of profit to steadily decline. The only robust economic growth that has come about in the developed world since then has either been from asset bubbles (Japanese real estate in the 80’s, US stock market in the 90’s, US real estate in the 00’s, Euro bubbles in the 00’s) or external demand (i.e. Germany after the introduction of the euro).

Capitalism requires infinite economic growth but we have a finite amount of space and resources. At 3% growth the global economy would have to double by 2060 and then double again by the end of the century. Even with a booming Africa, there’s no way we’ll achieve those numbers. The global economy grew at a snail’s pace in the early stage of capitalism (1500-1750) before the industrial revolution. Once economies reach the post-industrial stage, they stop growing like they used to (e.g. Japan after 1990) unless for the reasons stated above (asset bubbles or external demand). What truly drives robust growth rates is not the capitalist economy itself but rather the processes of urbanization of industrialization. The Soviet experience in the two decades after WW2 only further support this hypothesis.

These issues are entirely invisible at the micro level. And since there’s a finite amount of infrastructure that can be repaired, eventually Keynesian stimulus will be unable to prop up demand. If people will accept secular stagnation, the system will continue as it is. But most likely is that there will be challenges to it from both the left and the right.

I painfully read every sentence and studied every chart with intent to be better informed. The economy as regards the US can be summarized in far less:

1. We gave away our manufacturing base except weapons of war.

2.The remaining middle class jobs are low wage, no benefit, part time gigs.

3. The middle class does not have any money.

4. Middle class consumption has declined due to item 3.

5. Decline in consumption by middle class leads to fewer jobs.

6. The middle class are now the middle poor and economics needed to improve

their lives is all being spent on item 1.

Solution: Spent less on item 1 and more on item 6. Stop off shoring the few remaining good jobs.

We ceded our democratic institutions (yes, we used to have some) to neoliberal grifters. Just one tiny example: programs at my local public library, an institution voters have NEVER failed to support by passing every levy that has been put on the ballot, are now presented with corporate sponsorship. Pernicious and ubiquitous, this undermining of the most basic level of democratic governance must be reversed before we will ever address your items 1 through 6.

My crude attempt at “economics” was to reduce it to simple basics. Economics is not a science as some preach and practice. To the working class it is bread and butter. Indeed, pernicious (fatal) undermining of the democratic process lays at the core of the long lost American Dream.

Religion used to be the way the masses were placated.

This life may be bad but a life of everlasting bliss awaits you after death (so don’t worry about us exploiting you while you are alive).

Now we have economics.

You must abide by the laws of economics or terrible things will happen.

Now you just have to make sure that economics produces the results you want.

Generate a core that can only lead in the desired directions and insist everything is built on that.

The problem, economics has to describe the way the economy operates or it won’t work.

Neoclassical economics was around in the 1920s and was discredited after the Wall Street Crash and Great Depression.

Milton Freidman revamps it around the some core and it leads in the same direction.

1920s/2000s – high inequality, high banker pay, low regulation, low taxes for the wealthy, robber barons

(CEOs), reckless bankers, globalisation phase

1929/2008 – Wall Street crash

1930s/2010s – Global recession, currency wars, rising nationalism and extremism

The big things missing from neoclassical economics.

1) The effect of debt on the economy. Leading to Japan 1989, US 2008, Irish and Spanish real estate collapses, Greece’s collapse with austerity and the new normal of secular stagnation.

2) The difference between “earned” and “unearned” income. Leading to parasitical rentier economies, now spotted by one of today’s Nobel Prize winning economists “Income inequality is not killing capitalism in the United States, but rent-seekers like the banking and the health-care sectors just might” Angus Deaton. A floored model of global, free trade that doesn’t consider the minimum wage is set by the cost of living.

A floored model of global, free trade that doesn’t consider the minimum wage is set by the cost of living.

Western labour is priced out of global labour markets by the high cost of living in the West due to rentier activity.

Americans expect to get rich off of their neighbors inferiority, but this only works for all of us if we have enough imperialism to get rich off other countries resources and people. Then everyone in America, like Lake Wobegon, can be above average (if measured globally). Isn’t that what we have been doing since President McKinley?

Would not a third item missing in neoclassical economics be 3) Investment in productive assets vs financial assets?

I have added that one now for a comment in the FT.

3) Bank credit should be directed into productive investment in business and industry, not blowing asset bubbles (e.g. real estate) and other financial speculation.

I forgot it above, you are quite right.

Neoliberal economics is just a secular religion that favors the wealthy or powerful (as do all successful less secular religions).

The high priests are the Central Bankers.

You should worship them.

Agreed. But how is that reflected in Keen’s model? Not so much. I think Keen’s work is fantastic, but this coffee-demanding post refreshed my understanding of what a strain it is doing econometric modeling. Keen argues well for an analysis of emergent phenomena within a system, but bounding constraints of the sort you bring up can only appear — rather tepidly, I think — as rising prices. ??

As much as I like Keen’s work, I think he’s missed this in his model. And as far as rising prices go, that’s the first guess I would have, too, but I was referring to real GDP rather than nominal GDP, so rising prices won’t cut it. A lot of people like to forget about how compound interest works.

One way to look at it is that the low growth rates might not be the result of a struggling economy but rather that the economy growing the same way that it used to means that growth rates will head towards 0 as the surplus becomes a smaller and smaller fraction of the economy. But I think more relevant is the falling rate of profit in manufacturing.

How does one measure the falling rate of profit in manufacturing across countries, global supply chains and multinational corporations, many privately-held? I hear a lot about “falling rate of profit” but I can’t find any good data.

Read The Boom and the Bubble by Robert Brenner.

You could also check out Andrew Kliman or Michael Roberts, who has a very good blog.

Thanks for cites. I’m at least partly familiar with all but good to get reminders.

Still, I haven’t seen convincing data on the alleged “falling rate of profit.” I am not aware of anyone who has good insight into the profitability of privately-held manufacturing. What I do know, and have seen with my own eyes, is that private equity uses the cash flow generated by the business to pay off the debt incurred in buying the business. So reported net profits are a meaningless stat (because the interest payments and fees can be written off as expenses). The return to the investors shows up in the form of owning a valuable asset for which you paid hardly anything, not a steady stream of high reported profits.

Also, I’m not even sure what the appropriate denominator is for the stat “rate of profit.” If it is only equity invested, not debt borrowed, then I don’t think the profit rate has been falling in any long-term, world-historical sense. As Marxists become further removed from the actual world of business, I have less trust in their data.

Left:

Thanks for the reply. The rate of profit is calculated before taxes are paid and earnings shifted offshore.

Where r is the rate of profit,

r = (surplus value)/(capital invested)

So offshore havens don’t play a part in this.

What happens in reality is that some businesses do well and invest their surplus in productive capacity (plant equipment), and they will undercut their competitors with the increased efficiency. Market pressures then squeeze out the firms that can’t keep up. As time passes, this causes the rate of profit to fall (something that was noticed by Adam Smith and David Riccardo, among others).

r’ = (surplus-value)/(capital to be invested for the next period of production in order to remain competitive)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rate_of_profit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tendency_of_the_rate_of_profit_to_fall

Looking at Michael Roberts’ newest post, he confirms my suspicion. His chart show “rate of profit” in G7 – data source not cited by I presume I could dig it out. This (presumably) ignores the massive corporate shifting of profits out of the G7 to either China or off-shore tax havens.

See above. And check out these posts:

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2015/12/20/the-us-rate-of-profit-revisited/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2016/05/02/explaining-the-last-ten-years-keynes-or-marx-who-is-right/

https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2016/04/12/opening-the-panama-canal/

FYI, Keen has stated he’s pursuing the effect of “energy” on his model. I’ll credit him with at least the acknowledgement that economics occurs within the context of nature

This is thoughtful and interesting to be sure. But this doesn’t make sense to me:

“-Debt finances investment in excess of profits”

What about equity offerings. Lots of companies use equity to raise money for investment either in venture stage, IPOs or equity offerings by mature companies. In the latter category, the utility industry in particular finances hundreds of billions of infrastructure investment with equity. Not to mention piggy banks, but that’s micro. Whoa! Haha

Also, the 2009/2009 crisis (which this blog is the resident expert on so anything I could type here is simply a footnote reference to what I read here) was caused in large measure by fraudulent debt issued through a few channels of causation, not debt per se.

The deterministic mathematical modelling of free will is inherently an exercise in reductio ad absurdum — to a point anyway. More mathimatically put, it’s the attempt to estimate an n-dimensional point in n dimensional space through a n-k dimensional system that also lacks stationarity. Of course thats a linear analogy but it’s just an analogy. You can estimate a function with its linear approximation at least over short intervals.

Not to say it isn’t worth doing or that it can’t be done better than the “mainstream” method. So kudos to Professor Keen for doing this. But don’t end up like MIT professer and geek Ed Bucks who almost lost his mind up in a tree in New Hampshire watching deer thrugh binoculars thinking he could find equations that explain the “face of God” in animal nature and then apply it to humans. Whoa. He was in bad shape after a few nonths in the tree. Lost 30 pounds (of which 20 was probly not needed anyway). So it wasn’t all bad. That’s the thing — if you do this hard enough you can lose weight! Just dont freeze to death in the austere high peaks of thought. Ahhahahahahahahahaha. Sorry

Keen is using extremely general meanings, as such, I think he would consider equity as a form of collateral for debt. Similarly, ‘fraudulent debt’ is just debt with poor collateral. he seems to recognize only 2 sources for money: profits and debt. Ignoring (limited) natural resources is a simplification that also keeps the dynamical system away from the boundaries on growth imposed by the finite world.

Right. I’ve been reading Ingham’s “The Nature of Money” and that seems to be how equity is understood.

This is what happens when economists get all mixed up and believe they are physicists.

Next thing ya know, E=MC2 gets shoved in the model, and everything works!

Actuallly that’s one rare exception whre the formula works. This occurred to me after a few red wines and xanax after watching Adele videos you on Youtbe.

Economic Activity = Money x Cooperation^2.

It’s true! Think about it. Cooperation is an abstract idea but very precise referent for business activity. And here M growing while C is constant is zero real grwoth but nominal growth due to inflation of the money supply.

So E does equal MC^2 in economics. Of course the equation ignores everything that matters because reducing C to one number means child brothels are as economically valid as vineyards and wine stores. Of course you could also argue that ignores “law” since what’s illegal is not in GDP but law enforcement is. IT gets complicated.

So true. That maybe the catch der. The squared C can make it work, but not if it’s slave labor, or even sex slave labor, which is easier, iffen you’re female. [Guy slaves can’t just get away with laying around on their back, groaning a few times, then changing the TeeBee channel to a different cartoon with yer big toe.]

Playing the “Painted Black” riff on my guitar this morning. Almost getting it down. Still too slow tho. Have to memorize the notes, otherwise reading tabs is too slow.

Also sorta do Honky Tonk Women. That’s a fun one. You pull the strings two at a time bare fingered, like playing bass, to get the bouncy sound.

Also, possibly, Satisfaction, Whole Lotta Love, Sunshine of Your Love, Born To Be Wild and Layla.

This is fun! Not too hard to play the notes, even with all the finger nuances they do for effects. But getting the melody and even rhythm right is tricky. I have fat, retarded fingers. Hopefully that slowly improves. It has so far.

Song lyrics are streaming thru my head. Most will get me in trouble. But so what. Have to right them down quickly, otherwise they fade to ether. Fade To Ether – great song title there. Physics audio! Chromatic Scale. All music is Chromatic Scale Rules I’m learning. Nature is smart! All music has perfect order. It’s how Hendrix blew Clapton off the stage playing Nat notes like a swarm of hungry locusts. As long as they follow the rules, your jam sounds good!

Conversely the esoteric concept of – free will – itself can be argued to be deterministic due to its function in dawgs will. The whole edifice kinda goes poof if that truism is removed from the model…. eh.

Now for fun one can cross reference that with the evolution of the brain, currant knowlage about brain function and Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology for starters.

disheveled…. hard to get anywhere when one starts with the dawgs breakfast as input rather than an output…. btw I thought miss crow settled it… a smile on a dogs face….

The human psyche can fix almost anything, short of the metaphysical, unless yer trained for it.

Giant asteroids being problematic, unfortunately.

However, cognition can prevail, provided it doesn’t just get swallowed up into the sinus cavity, mired down in green sticky boogars until one sneezes and needs to clean the mess up, or maybe sinus drip takes it’s slow path thru back channels, thru murky dark tunnels, slowly moved by muscle contractions and attacked by acids and pharmaceuticals, picking up all sorts of BS along the way, prodded and partially devoured by scary alien looking micro critters, leaving only a partial chemical signature to be sniffed by shadowy operatives with their noses in all the wrong places.

Who wants to keep all that straight?

I thought that was a space alien in Figure 2 but then I told myself “No. Youre imagining things that aren’t there. Go have a piece of cake and a tea and relax.”

Thta’s what I did and forgot about it. But now you’ve just confirmed what I first thought! It’s a space alien looking at us. Look at those eyes! No kdding. What’s Professor Keen thinking, publishing stuff like this? What does this have to do with economics? This is like something out of Whitley Strieber’s “Communion”

There was a time when you could just ignore stuff like this and not take things so seriously when it comes to studying econ papers.

But then, eventually we all reach the age when even the mention of the word “oyster” invokes a smile creeping across one’s face.

Economists don’t have a chance.

So glad that I came back to check the tread and find a debate about metaphorical boogers.

I think he means ‘in excess of savings’ rather than ‘in excess of profits’.

Steve Keen at 7:00 in the morning. Makes me wonder if there is a hidden dynamic within the economy which is driven by all the people sensing that a certain energy is fading and that in turn creates a crash. Because Keen talks about the use of cheap energy to juice industrial economies as creating a pending crisis. And entropy inherent in the system. Maybe we have entropy sensors in our brains, next to our pineal glands. The intensity of the prosperity wave diminishes a tiny bit and we all know it. He seems to have refined his idea about cheap energy and combined it with finance – since finance serves an economy much the same way? Cheap energy and finance are both a source of debt which is the thing that reaches critical mass, imploding an economy. This macro model is a work of art (above). You can see the dynamic so easily. It’s almost like an instruction booklet, with illustrations on how not to play a one stringed instrument. How not to cancel out the good resonance.

The main of many reasons that economies under the current configuration of money creation is that when the “debt money” is created the interest money is not created, so no matter what kind of fancy reasoning or modelling one uses the economic result is always an unbalanced economy which can never pay off the debts plus interest and which determines the death spiral of all “debt based money” economies.

The only way this foundational flaw can be removed is for National governments to use their unique powers to create “money” (deposits, currency etc.) and spend it debt free into the economy which allows there to be enough money in the economy to pay off all consumer debt plus interest.

Otherwise we have economies in which wealthy elites eventually through debt own everything and all others are either poor or bankrupt.

Money is foundational to economy and how it is created is more important than how it is spent! Unless national governments are empowered and forced to create money and spend it interest and debt free into the economy we are simply re-arranging the deck chair on the Titanic when we need to melt the iceberg!

The trouble with these sorts of macro trumps micro analyses is that one doesn’t know at what point in a (bad) macro process one is in. If housing prices fall, is this a correction of previous (policy induced) excess or simply inexplicable destructive forces? The destructiveness of a substantial decline of housing prices is easily enough established (empirically) but is it creative destruction? So the embrace of theoretical complexity tends to generate policy prescription chaos. And this is before we get into considerations of democratic (popular) government. So the brites won this battle in the thirties (and the Lucas counter revolution has hardly triumphed in policy) and we have now a mixed economy in which an estimation of the impact of graft and corruption must be central to any macro projections – or more accurately macro projections are completely impossible. So economic thinking is always a hoax and you wasted your morning reading this article.

“democracy as populism” seems a convenient straw man. Blue-prints v. maps, and their relative usefulness…re-read in the context of the underlying class dynamics, which requires effort, especially given the effort put into making it virtually invisible.

I do not think I wasted my time reading this article much as I struggled to understand. Sometimes I have to read information many times in many formats to truly understand the idea–but it’s always worth one’s time to try.

I do not think economic thinking is a hoax – I just think economists are in the Aristotelian phase.

Remember how Aristotle rejected Democritus’s atomic theory and insisted that there were five elements only: earth, water, air, fire and aether? And how by doing so, he stifled scientific enquiry for almost 2000 years? Sure there were those who added their own theories onto Aristotle’s basic elements (the alchemists) but they were never able to predict anything from those theories (even aether wasn’t given up until Mickelson and Morley did their famous experiment). It took a rejection of Aristotle before we started actually understanding chemistry and gained the ability to make that chemistry work predictably.

Adam Smith has given economists their “earth, water, air, fire and aether” and although they add their own theories to Smith, they won’t reject Smith’s basic tenets, so they can’t get their theories to accurately predict anything, can they? They need to go back to analyzing smaller (micro) economies and comparing the differences and similarities and ask why…….just like the scientists did in the 1700 and 1800’s….

Well, this article does explain what is wrong with economic theory these days, doesn’t it?

And another economist trying to use science (which he obviously doesn’t understand) and math to come to some sort of economic conclusions when he doesn’t want (and tries to find excuses for) to understand the basics of of that profession. It is as though he sees a pile of uranium and decides to build a bomb without understanding the basics of uranium. It isn’t going to work.

As for his truisms: Well, yea, it used to be a truism that the sun orbited the earth and there were many mathematical equations to prove it…..

Nobody, not even in my microeconomics courses, ever said anyone had to understand what each individual consumer would do, anymore than a bomb builder has to understand what each individual U-235 atom will do. But we do need to know what consumers will do statistically, just as we do need to know, if we want to build a bomb, that U-235 is that part of uranium that is the most useful for bomb building and that U-235 is statistically 0.7% of natural uranium.

As for water? No you don’t need to understand what each individual molecule will do, but you’d better understand the H2O phase diagram or you are going nowhere……

Oh, and that n-body problem? Every single astrophysics student is required to handle that problem at least once in his education. Yes, you CAN set up the equations using Newtonian physics, it’s just that it is such a number cruncher that no one can solve it without massive, massive computer use. If we didn’t have a solution to the 3 body problem do you really think we could have sent a satellite to Pluto using Jupiter as a “sling shot”?

And then there is his misunderstanding of the “butterfly effect”? – It’s about getting initial conditions right, so no rolling your pencil off a desk isn’t going to cause Jupiter to move to the other side of the sun(??? Jupiter orbits the sun every 4,330.6 days, so, yea, it sees the opposite side of the sun routinely…) in a billion years….

And Mandelbrot’s equations? We’ve been doing recursive equations for many, many years – what Mandelbrot did differently is to use a computer as a number cruncher……but what an enlightenment!

Sorry, but unless you understand the real basics of your profession, you can’t understand just jump in and develop some theory based on “truisms” and then add math to it and think it is going to work. Non-scientists try to do that all the time – that’s why there are so many nutty theories running around in rag-mags about science.

So, no sorry, any economist who refuses to understand what microeconomics is trying to tell him (because yes, economics IS about human behavior), is not going to fair any better than any other WAG from any other economist who just wants to jump in from the top.

Microeconomic trends may be very different for different groups of people – shouldn’t economists be trying to understand why instead of just ignoring them? Maybe then, just maybe, they would learn something useful about their “science”?

You are missing the point. derive the three phase diagram from 1 molecule of water. impossible. phase change is an emergent phenomena; it does not happen til you have billions of H2O’s interacting.

I think you misread……

“As for water? No you don’t need to understand what each individual molecule will do, but you’d better understand the H2O phase diagram or you are going nowhere……”, the point being that you DO need to understand the basics of what all those molecules as a group will do, if you want to understand why ice forms, etc….

Similarly, you do have to understand what groups of people will do to understand economics. No, not all groups of people are the same, and no, H2O doesn’t act like what a group of NaOH molecules act like – you need to understand WHY the two groups are different to have a grasp on your “science”……

And that’s what Keen wrote. You’ve let your adrenaline run away with you.

I think you need to reread the article. Keen rejects microeconomics as a tool for understanding macroeconomics….

“So macroeconomics cannot be derived from microeconomics. But this does not mean that “The pursuit of a widely accepted analytical macroeconomic core, in which to locate discussions and extensions, may be a pipe dream”, as Blanchard put it. There is a way to derive macroeconomic models by starting from foundations that all economists must agree upon. But to actually do this, economists have to embrace a concept that to date the mainstream has avoided: complexity.”

and:

“The impossibility of taking a “constructionist” approach to macroeconomics, as Anderson described it, means that if we are to derive a decent macroeconomics, we have to start at the level of the macroeconomy itself. ”

Keen thinks that if he makes macroeconomics more “complex”, well then all will be well….but, sorry, it doesn’t work that way. You cannot take a bad theory and doctor it up with “complexity” to make it a good theory. If that were true, then the alchemists of the middle ages would definitely have been able to make gold out of lead……

You need to go back to basics and start analyzing the smallest units you can and start asking why they are the same and why they are different……and the smallest units are in microeconomics……why so many who have tried this have failed is because they tried to make microeconomics fit their pet theories instead of trying to understand and ask why…..kind of like a “scientist” assuming that since some uranium turns into lead, then lead must turn into gold someday…..

It might be that microeconomics and macroeconomics are two different endeavors. Just as many body physics is different from elementary particle physics. Many body physics does not need elementary particle physics to exist. Even if physicists understand that “macro” bodies are made up of “micro” particles they could come up with ways to model macro phenomena without having to analyse the “smallest units”, ie subatomic particles.

No. Emergent Phenomena is a widely understood topic in science. Life for example is an emergent phenomena. So is entropy.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergence

that makes me feel better because I was hesitant to move anything in my apartment after reading that point about Jupiter. I wouldn’t want to be responsible for something catastrophic. Even if i nobody knew it was something I did. I’d know. That’s where it all comes down on your head. Eventually.

“has dominated the development of mainstream macroeconomics with the proposition that good macroeconomic theory could only be developed from microeconomic foundations. Arguing that “the structure of an econometric model consists of optimal decision rules of economic agents” (Lucas, 1976, p. 13)”

This had been refuted long time ago. For example, under marginal theory postulates, a downward push on wages among competing producers might lead to an effective aggregate demand slump at the macroeconomic level.

I meant to say marginal utility theory

“if there is a hidden dynamic within the economy which is driven by all the people sensing that a certain energy is fading..”

I believe the ‘energy’ you’re referring to is called purchasing power

that or the unspoken realization that growth requires long term maintenance and we can see just far enough in our imagination to know things are getting out of balance, or whatever… it’s like we have a sense of the imbalance to come, we slow down and curb our enthusiasm, the economy stumbles a little, the state freaks out, the bankers feed the beast with more and more money… but it doesn’t really start with the banks – it starts with an innate sense in each one of us that things are unsustainable. Otherwise there would be plenty of animal spirits to make things go forward even without the first stimulus… maybe

“•The employment rate (the percentage of the population that has a job) will rise if the rate of economic growth (in percent per year) exceeds the sum of population growth and labour productivity growth;

•The percentage share of wages in GDP will rise if wage demands exceed the growth in labour productivity; and

•The debt to GDP ratio will rise if private debt grows faster than GDP.”

All these truisms are fake because they ignore the other sectors of the macroeconomy, any of which will turn these on their collective heads. GDP=C+G+I+(X-M)

I don’t believe Keen subscribes to these truisms and fear he has been misquoted. Anyone with even a scant understanding of the sectoral balances model will immediately smell bullshit.

microeconomics – you versus the system.

macroeconomics – the system versus you

Thought I could maybe, possibly, not have to buy Keene’s new book in the immediate future, but damn, after reading this post, I’ll have to order it on-line (from Powell’s, not Amazon! you slaves of capitalism).

I really like his observation of building a model of your world from the pieces and the relationships that exist at that level. Not the pieces and relationships that exist at a higher or lower level. This modeling technique has been around for quite some time, but he put it clearly. That explains a lot, really.

You might want to integrate waves of technological change and resource development. Walt Rostow created a nonlinear dynamic model doing exactly this back in the early ’90s. I think he even did a little work with the chemist you mentioned at UT. He was fascinated by strange attractors.