By Tim Lang,Professor of Food Policy at City University London’s Centre for Food Policy since 2002. He has been a consultant to the World Health Organisation, FAO, UNEP and on food security to Chatham House; and special advisor to four House of Commons Select Committee inquiries on food standards, globalisation and obesity. Originally published at Open Democracy

We see Liam Fox warming up a US-UK trade deal, while Michael Gove assures consumers that animal welfare and food quality standards are safe in his hands. This doesn’t add up.

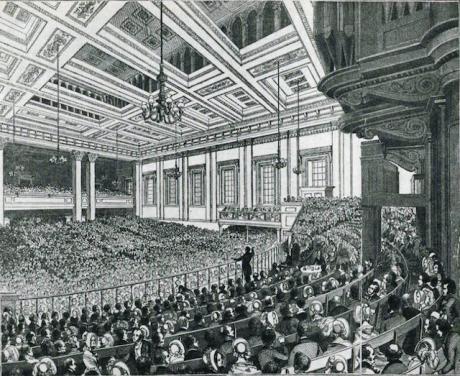

A meeting of the Anti-Corn Law League in Exeter Hall in 1846. Wikicommons. Public domain

If Brexit is supposed to improve Britain, then it must do so for food. In astonishing arrogance or myopia, British politicians collectively ignored food in the run-up to the 2016 Referendum, other than to draw upon decades of pillorying the Common Agricultural Policy to knock the EU and, in the Tories’ case, to promise to continue CAP farm subsidies till 2020 (now extended to 2022).

Anyone would think farmers feed people! Actually farming is already a small, shrinking but noisy sector of the UK food system. It makes up only 8% of the value added by the whole UK food supply chain. Manufacturing, Retailing and Catering make up over three times more each. But food is what the 65 million Brits eat every day, £203 bn’s worth a year. We get 31% of our food from within the EU, a fact which seemed to elude politicians as they vied for votes. And the food trade gap is massive. We import over £42bn’s worth and export £20bn. In come fresh fruit and veg. – out go soft drinks, (and whisky) and biscuits. Not a great health exchange!

To exit the EU without any food plans or national debate could be an act of monumental stupidity, unless there is a Plan B no-one told us about or the idea was to get food from somewhere else or just leave it to the food industry to sort out. I suspect a mix of these, not least since the Tory Government and Party – like Labour – are fundamentally split about what they want. One faultline is Europeanisation vs McDonalidisation. That’s why we now see Liam Fox warming up a US-UK trade deal (the US mass agri-food industry is salivating) while Michael Gove is assuring consumers that animal welfare and food quality standards are safe in his hands. This doesn’t add up.

As we know, the whole Brexit issue is an argument about Progress and, since it is in power, the Right’s vision for British capitalism. Alas, some of the faultlines now emerging amidst the chaos, divisions and drift have echoes with the past. A failure to consult the public. Dishonesty. Plus genuine political differences: mercantilism (protected food supplies), neo-imperialism (get others to feed us), nationalism (grow more here), all cut through by the new politics of ecosystems and health. The gods spare us, if the UK seeks to emulate the diet-related ill-health of US citizens on low incomes, where obesity is rampant without the healthcare.

The bad news about Food Brexit is that this is all coming upon us in pressurised and dramatic ways. The food industry is more worried by a Food Brexit than it has been by anything for years. It is massively reliant on EU migrant labour for ‘British’ food. An entire system of supply, infrastructure, taste, cost, and standards is to be swept away in 19 months’ time, as colleagues and I show in our new report on Food Brexit, the first comprehensive overview of what’s at stake.

Food is a bellwether of progress. If the supply or the quality of our food is damaged by Brexit, those responsible for those failures will deserve to pay a high price. The most immediate issue is food prices, which have direct impact on consumption, and are already rising in a time of stagnant wages. Some Tories simply want us to source from wherever is cheapest. China? India? Tory MP Jakob Rees-Mogg has even mused about the case for getting our food standards to be closer to India’s. He’ll regret he said that, I suspect. Cheap food, low standards is risky politics.

Corn Laws Revisited

The British have become accustomed to cheap food. This assumption has gradually been hard-wired into British food culture since the early nineteenth century, due to a 30-year political battle over what were known as the Corn Laws. Beginning in 1815, these imposed duties on imported food, thus protecting UK farmers from external competition, and keeping food prices high. They were enacted blatantly to suit the UK landed class.

But the UK was in the process of industrialising and democratising its Parliament. The widening of the voting franchise really began with the Great Reform Act of 1832; became more serious (but still inadequate) with the Second Reform Act of 1867; and was only resolved with full one-person-one-vote rights in the twentieth century.

Compared to that century-long march for political democracy, the 30-year fight over the Corn Laws seems positively speedy, but its consequences are once again resurfacing. The 1846 Repeal of the Corn Laws set the seal on what is known as Britain’s desire for a ‘cheap food policy’. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Britain’s rural population was leaving the land and becoming the urban working class. For 30 years, culminating in the 1846 Repeal of the Corn Laws, political arguments raged about cheap versus expensive foods, the role of food in setting wage levels, the political risks of what we’d now call ‘food security’. Above all, which class interest would drive British capitalism: old aristocracy or new industrialists? The people were excluded but getting noisy; demands for voting franchise were building up.

Fresh from naval and land victories in the Napoleonic Wars and in the process of massive colonisation and expropriation, the UK Parliament in the end took the momentous decision to repeal the tariffs. A slow process began of abandoning domestic farming, and instead importing food from within the Empire, whichever country offered it most cheaply.

Taking Back Control

It was not until the two world wars of the twentieth century shook this political complacency that governments again reviewed the UK’s food security policy. And by then there had been a furious battle over legal restrictions on food adulteration and poor quality, not sorted till the 1890s. Reluctantly in World War 1, and then in desperation in World War 2, the UK relearned what other rich countries had not ‘unlearned’ – that it makes sense to retain a sound food production base. That’s why the UK set up its own agricultural policy in 1947, under Labour, a system of farm support which served the same purpose as what the Common Market created a decade later with the Common Agricultural Policy – security for farming to produce food at home.

Negotiating to join the EU in 1967-73 switched subsidy systems but with shared intent. It meant abandoning the relics of Empire which had fed industrialising Britain in the nineteenth century: Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the looser historical food links such as with Latin America or the Baltic.

Joining the Common Market coincided with a revolution in the food system: more processed foods, supermarketisation, cafés, taste changes, rises in diet-related disease (most recently obesity and diabetes) and thus huge externalised healthcare and environmental costs. Aspects of these changes have been felt everywhere, first in the western rich world and now even in low and middle income countries. This has delivered a situation the proponents of ‘cheap food’ never dreamed of, a flood of what nutritionists now call ‘ultra-processed’ foods, unnecessarily high in fat, salt and sugar – the opposite of the Mediterranean diet.

In a class-divided society such as the UK, we can be saddened but not surprised that British people on low incomes spend proportionately more of their disposable incomes on food than do the rich. The money spent on food in the UK has grown in absolute terms, while in relative terms food expenditure as a proportion of disposable incomes has fallen. This has been the success of both the EU and before that the UK’s 1947 Agriculture Act which in effect repealed the 1846 Repeal of the Corn Laws and committed the UK to taking measures to stabilise food supplies and prices.

Those policy shifts took over a century, two world wars and a recession. Food Brexit today is being rushed upon us in less than two years, without debate, and reigniting old debates about cheapness, quality and sources. The Corn Laws debate lasted 30 years and split the Tory Party. The UK then had a navy to protect its supply chains. Today, we have just 77 ships, compared with the hundreds in 1939, not that anyone officially anticipates World War 3 when long routes would again be problematic, of course.

Amidst its current concerns, it is essential that the UK Government is held to account. We need a clear and explicit commitment to ensuring a sufficient, sustainable, safe and equitable supply of food, with realistic plans for how this will be achieved when and if the UK is no longer in the EU.

I predict a demand for allotments…

One of the more astonishing things about the Brexit vote is that so many farmers voted for it, which is surely a case of turkeys voting for Christmas. A friend of mine who lives in a small village in the north Yorkshire moors has told me most of his neighbours voted for Brexit, out of (so far as he can work out) pure bloody mindedness over whatever it was that has been annoying them.

The CAP has its stupidities – but oddly, as the British dislike it so much – it was originally based on the British post war system (something this article touches on, but is rarely mentioned) – the French and Germans actually admired how the British made such a sharp reversal in the post war years and rebuilt agriculture, and they wanted to do the same, albeit from mostly a higher base.

One of the oddities of British politics is that the the agriculture sector has such a strong political hold on the country, vastly out of proportion to its size and economic importance. While the landed aristocracy were soundly beaten in the end over the Corn Laws, post war policy (before and after the EU) inadvertantly built up a new aristocracy of big corporate farms, with a unified policy of making taxpayers hand over billions to them in exchange for thrashing the countryside. They succeeded admirably. Much of the bad reputation the UK built up over the years in the EU was directly due to the determination of successive UK governments to distort agriculture policy in favour of big farms – making progress in many other areas impossible. Continental countries always I suspect found it baffling that the UK would sacrifice so much political capital for such a small gain.

But now it seems Brexit will change things irrevocably. Any deal with the US will almost certainly force the UK to adopt US standards of food production, which will unquestionably lead to UK products being excluded from Europe – this will be particulary devastating for the dairy industry, especially in Northern Ireland. And I doubt very much if UK farming will continue to recieve such generous subsidies from London that it did from Brussels. So the only possible good result from this would be a vast swathe of farmland going fallow. Good for wildlife, I doubt though anyone else will benefit.

Farms and farmers are at the core of the Tory party, and are Authoritarian all.

They resent being under rules form others. I was surrounded by this group in my childhood and at school, and was very familiar with their customs, beliefs and behavior.

Not so much now as I wandered away.

Pretty much agree. I have family who farmed. The problem seemed to me to be resentment of bureaucracy, any bureaucracy. The EU is a bureaucracy, who make them fill out forms to claim money, and they hate paperwork.

I wonder how many Brexiters are dyslexic?

According to MIT, the top exports of the United Kingdom in 2015 were Gold ($41.6B), Cars ($40.8B), Packaged Medicaments ($19.9B), Gas Turbines ($14.7B) and Refined Petroleum ($13.2B). The top imports were Cars ($49.9B), Packaged Medicaments ($21B), Refined Petroleum ($20.2B), Crude Petroleum ($17.3B) and Vehicle Parts ($15B).

The cars and packaged medicaments nett out to $10B of car imports. Then there’s about $40B total of car parts and nett oil imports. So the biggest UK exports by value are gold! and gas turbines.

According to ons.gov.uk, the EU countries are hugely important trade partners for the UK. In 2016, the EU accounted for 48% of goods exports from the UK, while goods imports from the EU were worth more than imports from the rest of the world combined.

So why exactly does the UK need to do a trade deal with US rather than the EU?

because it’s a more sovereign when us tells the uk what the do and take it or leave it, rather that sit and negotiate within eu as an important part of the eu?

wow could have had European standards and went for U.S. ones instead, what a mistake!

I guess the criteria for doing EU exit correctly is 1) don’t be a neoliberal hellhole first and foremost so the UK really shouldn’t have tried. Switzerland does not being a EU member right but has the money for it, Greece should have done it, but if the UK it just going to use it to make trade agreements with and be more like the U.S., really why bother?

The landed aristocracy were beaten by two changes in British society.

Ending the Corn Laws was one, as the article mentions, but the other is equally important. Britain became a debtor nation in the fight against Republicanism and democracy in France and Europe (and later America). This had required the rapid development of the London bond market where government loans were securitized and became attractive investments for all the capital flight of the world.

Those aristocrats who failed to see the significance of the national move from exchanging value (gold and silver) to exchanging paper credit notes very soon found their returns were inadequate.

PK’s final paragraph is portentous and should be carefully considered. The likely shorter life spans that a US trade treaty and lowered food standards (together with privatized NHS) will bring comes at a time of significantly decreased fertility rates amongst men.

It won’t happen…..

“the UK parliament … took the momentous decision to repeal the tariffs” in this article is misleading.

The fact is the UK parliament had adopted a smuggling economy to defeat the Continental System and the merchants loved it. Government found it could not recover its former revenue from Customs and Peel let the merchants off, instead taxing the wages of working men, a form of partial slavery that remains with us today.

That is the factual background to ‘momentous decision to repeal the tariffs.’