Having chronicled the crisis in gory detail, it’s frustrating to see reporters who were asleep at the outset repeat their mistakes or for younger ones, not bother mining their employer’s archives.

For reasons beyond my comprehension, a move is afoot to designate August 9, 2007 as the start of the crisis because that when BNP Paribas froze the assets of three funds because they said they could no longer value the CDOs in them. On August 9, the Fed and the ECB reacted by making liquidity injections.

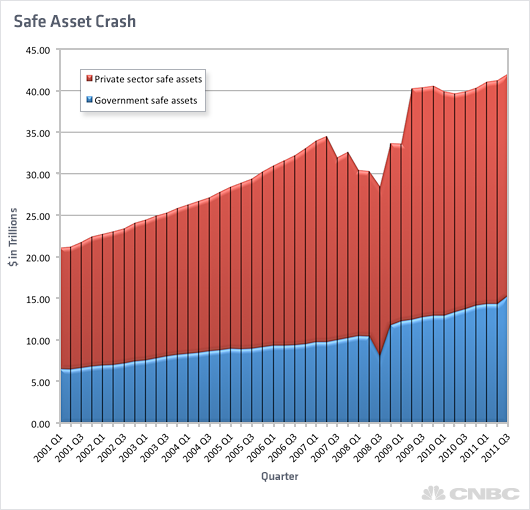

We have now had terabytes of material written about the financial crisis. I challenge anyone to cite a book (books are almost without exception better researched than articles) written prior to this year that calls that event the beginning of the crisis. Even a CNBC article in 2014 that has the Paribas move and central bank reaction as its anchor. It actually starts with the premise that that might be the beginning of the crisis and concludes that that’s not the case, that the “crash in safe assets” started earlier, per this chart:

And our post on the date of the August ECB liquidity injection shows this was far from the first shock to the markets:

The ECB made an unprecedented offer of unlimited funds to member banks as the demand for cash soared as a result of Paribas freezing redemptions of three funds. Mind you, these funds only had $2.2 billion of assets, far less than the troubled Bear hedge funds. The reaction seems disproportionate, unless you factor in that there are widespread rumors of other funds in distress, and not in strategies that have much to do with subprime (i.e., market neutral, statistical arbitrage, event driven)…

From Bloomberg:

…..The ECB’s decision, just one week after the German government arranged the bailout of IKB Deutsche Industriebank, is confirmation that the subprime debacle isn’t contained within the U.S….

“Banks reacted to the ECB’s `sale’ offer in a similar way one would react to a sale in a department store” and “got all the money they could,” said Ulrich Karrasch, a money market trader at HVB Group in Munich….

Bear Stearns triggered a decline in the credit markets in June after two of its hedge funds faltered, leaving investors with a near-total loss and forcing the New York firm to put up $1.6 billion in emergency funds to keep one of the funds from collapsing.

Default rates on home loans to people with poor credit, known as subprime mortgages, are at a 10-year high. American Home Mortgage Investment Corp. this week became the second- biggest U.S. home lender to file for bankruptcy this year, joining more than 70 mortgage companies that have had to close or seek buyers.

The credit crunch also tainted the market for corporate takeovers, as investors became increasingly wary of buying the high-yield bonds and leveraged loans that private equity firms used to finance deals.

The fact is that the Fed and other central banks were way behind the eight ball and continued, even through the Lehman failure, to be slow to anticipate events and overreact when they took place. I gasped out loud in May 2007 when I saw Ben Bernanke declare that subprime was contained and estimated potential subprime losses at $50 billion. At that point, the consensus among private sector analysts was a minimum of $150 billion. Anyone who was even remotely following the subprime saga had just seen Bernanke telegraph that the Fed has absolutely no idea what was going on.

Similarly, remember the panicked over-large rate cuts? The cliche quickly became “75 [basis points] is the new 25” which is part of why we got to super low rates?

I scanned my archives and could provide headlines and snippets that would show analysts, commentators, and more important, the MSM and Mr. Market were panicked well before Paribas shut the door on its three subprime-related funds.

The crisis had four acute phases, the first of which was July-August 2007, when the subprime commercial paper market seized up. This was triggered by the failure of two Bear Stearns subprime hedge funds in June. There was some to-ing and fro-ing as Bear was attempting various partial liquidation strategies and other salvage operations with angry Wall Street firms that had loans against fund collateral, so that failure doesn’t have a tidy date, for those who like false precision.

The subprime origination market also had its last gasp in July 2007. Early July was also when rating agencies started slashing ratings of subprime mortgage bonds. And this was even more meaningful than you might think because the ratings agencies almost without exception downgrade only after Mr. Market is saying it expects bigger credit losses, as in the ratings agencies follow rather than lead investor reassessments.

So if you must pick an event (as opposed to a date) for the start of the crisis, it would be the failure of the Bear Stearns hedge funds, but it’s every bit as reasonable to peg it to the critical knock-on effect, which was the seize-up of the asset-backed commercial paper market, which was then roughly half of the size of the total commercial paper market. Alert retail investors were calling their money market funds and asking about their subprime exposure well before August 9.

Even though it seems to be over-egging the pudding to mine the NC archives, we started going into daily coverage of crisis related matters as of the implosion of the two Bear Stearns subprime-related hedge funds. Prior to that, we’d been merely giving frequent sightings on how credit risk was grossly underpriced across all types of borrowing, as opposed to tracking more specific market events in detail.

And we had our own version of a spike in the VIX as another crisis indicator. Naked Capitalism had barely started, and had only 200 daily readers as of early June. I had set targets for how many reader I’d have to have at 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months for me to keep the site going. The six month deadline was June 18.

The Bear Stearns hedge fund meltdown led to a 5+x increase in traffic. And wheels obligingly kept falling off the financial system every time it looked like we might miss our traffic targets.

These three posts of many supply provide additional evidence that the crisis was underway before the Fed was jolted out of its slumber by a big bank doing Something Untoward in August 2007:

Even Brokers Admit Housing Market is Desperate June 21, 2007

Could Bear Stearns Fail? June 25, 2007

“What Happens To MBS and CDOs and CDS When Subprime Defaults Rise?” July 12, 2007

And not to pat ourselves on the back, but we explicitly called the start of the credit crisis, although we expected something more Japan-like (as in ratchets downward over years and zombification, and not ever more acute episodes, culminating in the Mother of All Market Panics of September-October 2008) on July 11, 2007, almost a month before pet date of revisionist historians.

The full text of our post Has the Credit Contraction Finally Begun?:

Readers of this blog know that I have been concerned about the state of the credit markets for some time. We’ve had (until the last month or so), rampant liquidity feeding asset bubbles in virtually every asset class except the dollar and the yen, tight risk spreads (that means inadequate compensation for risk assumption), lax lending standards (that helped create the aforementioned bubbles), and increasing inflation pressures.

Now what inevitably happens when credit gets too cheap is that borrowers go and buy stupid things, like housing they can’t afford or illiquid faith-based paper or overpriced companies, and at some point enough of this speculation, um, investment, turns out badly that lenders get nervous and start turning off the liquidity spigot. And the wilder the party has gotten, the worse the hangover.

Now heretofore, I have merely fulminated about this situation, because at some point, the correction will begin. But it’s very easy for people like me to expect things to get rational way before they do (look how long the 1980s LBO wave, the Japan bubble, and the dot com mania lasted).

So as much as I have felt for a long time that these conditions were not sustainable, and were likely to end badly, I have refrained from making a call. Smarter people than me, like Martin Wolf of the Financial Times, have similarly pointed out that the global equity markets are considerably overvalued and are certain to mean-revert, but he pointedly refused to say the markets were near a peak.

But the few times I’ve made a specific investment call (and it’s been very few times, believe me), I’ve been proven correct. So as a matter of public service (and doubtless ego as well), I’m making one now.

The bear credit market has begun.

Why do I think now is the turning point? There has been considerable nervousness over the last few weeks, due first to the Bear Stearns meltdown and the parallel development of a sharp, pattern shattering rise in Treasury yields that many felt was the sign of a fundamental change in sentiment. And if I am right and the contraction has begun, many will legitimately see the Treasury break as the starting point.

But I see the following as the signs:

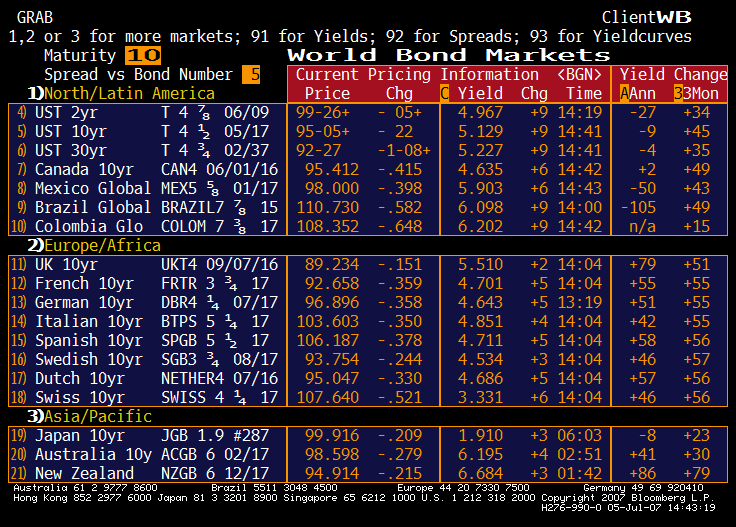

Liquidity is falling on a widespread basis. Bond yields are rising in all major bond markets (hat tip to Michael Shedlock for the chart) below):

Investors are increasingly reluctant to shoulder risk. A number of LBO financings have either not gone forward or have had to offer improved termsThe reaction to the downgrades by Moody’s of 399 subprime bonds from 2006 and another 52 from 2005, about $5.2 billion in face value, and the announcement by S&P that it will likely downgrade 612 issues, representing $12 billion in original issue price and about 2.1% of the market, has precipitated a reaction that at first blush is way out of proportion to the event. After all, $5 billion or even $12 billion worth of bonds isn’t much at all, even if there are forced liquidations (any pension funds or insurance companies holding formerly investment grade paper that has been downgraded to junk will in most cases have to sell for regulatory reasons).

Now as we go through the rest of this post, skeptical readers will doubtless think, “But this is mainly about subprimes. This is contained.” Yes and no. Forced sales. losses and general embarrassment (if not loss of capital) will create new found sobriety, which will lead to less liberal credit terms across the board. As we said yesterday, nearly all participants have been playing a game of musical chairs, trying to stay in the game until the last possible minute so as to extract maximum profits, under the cheery assumption that there won’t be a rush for the exits.

Now contrast that fact set with this Bloomberg story, “Subprime Losses Drub Debt Securities as Credit Ratings Decline“:

On Wall Street, where the $800 billion market for mortgage securities backed by subprime loans is coming unhinged, traders are belatedly acknowledging what they see isn’t what they get.

As delinquencies on home loans to people with poor or meager credit surged to a 10-year high this year, no one buying, selling or rating the bonds collateralized by these bad debts bothered to quantify the losses. Now the bubble is bursting and there is no agreement on how much money has vanished: $52 billion, according to an estimate from Zurich-based Credit Suisse Group earlier this week that followed a $90 billion assessment from Frankfurt-based Deutsche Bank AG.

Even the world’s second-largest company by market value must “triangulate” the price of an asset-backed bond when it gets bids from traders, said James Palmieri, an investment manager at General Electric Co.’s Stamford, Connecticut-based GE Asset Management Inc., which oversees $197 billion.

“We do not foresee the poor performance abating,” Standard & Poor’s said yesterday as it threatened to downgrade $12 billion worth of securities backed by subprime mortgages. Losses “remain in excess of historical precedents and our initial assumptions,” S&P said.

Moody’s Investors Service went further, lowering the ratings on $5.2 billion of subprime-related debt.

Why Now?

More than a few investors would like to know what took the New York-based rating companies so long to discover a U.S. liability of Iraq-sized proportions.

“I track this market every single day and performance has been a disaster now for months,” said Steven Eisman, who helps manage $6.5 billion at Frontpoint Partners in New York, during a conference call hosted by S&P yesterday. “I’d like to understand why you made this move now when you could have done this months ago.”

Eisman was referring to the rise in borrowing costs that has forced thousands of Americans to default on their mortgages.

A total of 11 percent of the loan collateral for all subprime mortgage bonds had payments at least 90 days late, were in foreclosure or had the underlying property seized, according to a June 1 report by Friedman, Billings, Ramsey Group Inc., a securities firm in Arlington, Virginia. In May 2005, that amount was 5.4 percent.

Investors depend on guesswork by Wall Street traders for valuing their bonds because there is no centralized trading system or exchange for subprime mortgage securities. Credit rating companies supported high prices because they failed to downgrade the debt as delinquencies accelerated.

Headed Lower

While there’s no consensus on prices, traders agree that the bonds are headed lower. Some of the securities have already declined by more than 50 cents on the dollar in the past few months, according to data compiled by Merrill Lynch & Co.

One subprime mortgage bond, Structured Asset Investment Loan trust 2006-3 M7, is valued at about 91 cents on the dollar to yield 9.5 percent, according to the securities unit of Charlotte, North Carolina-based Wachovia Corp. Merrill Lynch in New York puts the price of the same security at 67 cents to yield 18 percent…..

The downgrades may force sales, giving investors who have relied on estimates real prices to value their own holdings. That would be novel in the market for asset-backed bonds.

The securities, backed by everything from student loans to auto payments to mortgages, almost doubled to about $9 trillion outstanding since 2000, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

Masking Swings

At least a third of hedge funds that invest in asset-backed bonds pick and choose values for their investment that help mask wide swings in performance, according to a survey of 1,000 funds worldwide by Paris-based Riskdata, a risk management firm for money managers.

“If you have five different brokers you will get five different quotes, so if you don’t have an objective valuation process you can choose the quote which for you is the most interesting,” said Olivier Le Marois, chief executive officer of Riskdata. “There’s no consensus on where the market price is.”….

Wall Street has benefited from keeping the so-called structured finance market opaque. Securities firms collected $27.4 billion in revenue from underwriting and trading asset- backed securities last year alone, according to Kian Abouhossein, an analyst at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in London.

Investors struggle when they need to set values for subprime and lower-rated debt because the bonds trade infrequently, said Dan Shiffman, vice president at American Century Investment Management in Mountain View, California.

“If it’s a bond that requires a lot of credit work and if that bond hasn’t traded for some time, it’s very difficult to assess,” Shiffman said. American Century manages $5 billion in mortgage-backed and asset-backed bonds….

Trace system. Levitt is a director of Bloomberg LP, the parent of Bloomberg News…Traders in subprime and low-rated asset-backed securities may resist any move to shine a light on the trades because they benefit from having their moves kept under wraps, said American Century’s Shiffman. “They might get better execution rather than having the bonds flagged all over the market,” he said.

So what do we have here? We have a fairly large amount of bonds in aggregate, and for many of them, even the most sophisticated players didn’t know what they were worth in a good market. A bid of 91 from one dealer and 67 from another on the same security is a staggering difference. And now we are having forced liquidations, and it’s unlikely there will be enough buyers because more downgrades are in the works. Speculators are likely to wait till the carnage gets worse.

But the real news isn’t these immediate downgrades. It’s the fact that the rating agencies have finally gotten religion and are going to start going through these instruments with a much more jaundiced view. Mind you, they’ve started with subprimes, but they will get around to CDOs, so this is the beginning of a long and painful process. And even if they are cautious and late to the game, this process is going to force more trading, and the price discovery is going to be very painful.

And most important is that Standard & Poors has announced it is changing its methodology (and we imagine Moodys and Fitch will have to follow). Tanta of Calculated Risk was good enough to post the bulk of S&P’s lengthy press release. Let me give you a few of the high points:

Many of the classes issued in late 2005 and much of 2006 now have sufficient seasoning to evidence delinquency, default, and loss trend lines that are indicative of weak future credit performance. The levels of loss continue to exceed historical precedents and our initial expectations.

We are also conducting a review of CDO ratings where the underlying portfolio contains any of the affected securities subject to these rating actions…On a macroeconomic level, we expect that the U.S. housing market, especially the subprime sector, will continue to decline before it improves…

Although property values have decreased slightly, additional declines are expected. David Wyss, Standard & Poor’s chief economist, projects that property values will decline 8% on average between 2006 and 2008, and will bottom out in the first quarter of 2008.

It’s pushing 3 AM, so I will be terse in my comments here. An 8% decline is a much bigger number than most mainstream forecasters have put forth (although some specialists have put forth even grimmer estimates). That in turn has nasty ramifications for the economy, and frankly seems inconsistent with a bottom in 1Q 2008.

Back to S&P:Data quality is fundamental to our rating analysis. The loan performance associated with the data to date has been anomalous in a way that calls into question the accuracy of some of the initial data provided to us regarding the loan and borrower characteristics. A discriminate analysis was performed to identify the characteristics associated with the group of transactions performing within initial expectations and those performing below initial expectations. The following characteristics associated with each group were analyzed: LTV, CLTV, FICO, debt-to-income (DTI), weighted-average coupon (WAC), margin, payment cap, rate adjustment frequency, periodic rate cap on first adjustment, periodic rate cap subsequent to first adjustment, lifetime max rate, term, and issuer. Our results show no statistically significant differentiation between the two groups of transactions on any of the above characteristics. . .

Translation: they lied to us. Remember, rating agencies don’t do due diligence. Back to the press release:

In addition, we have modified our approach to reviewing the ratings on senior classes in a transaction in which subordinate classes have been downgraded. Historically, our practice has been to maintain a rating on any class that has passed our stress assumptions and has had at least the same level of outstanding credit enhancement as it had at issuance. Going forward, there will be a higher degree of correlation between the rating actions on classes located sequentially in the capital structure. A class will have to demonstrate a higher level of relative protection to maintain its rating when the class immediately subordinate to it is being downgraded. . . .

OK, now they will be quicker to downgrade higher rated tranches if the lower graded tranches that were providing credit support get whacked. That only makes sense, and one has to wonder at how they could have justified their old posture. To S&P:

Given the level of loosened underwriting at the time of loan origination, misrepresentation, and speculative borrower behavior reported for the 2006 vintage, we will be increasing our review of the capabilities of lenders to minimize the potential and incidence of misrepresentation in their loan production. A lender’s fraud-detection capabilities will be a key area of focus for us. The review will consist of a detailed examination of: (a) the overall capabilities and experience of the executive and operational management team; (b) the production channels and broker approval process; (c) underwriting guidelines and the credit process; (d) quality control and internal audits; (e) the use of third-party due diligence firms, if applicable; and (f)secondary marketing. A new addition to this review process will be a fraud-management questionnaire focusing on an originator’s tools, processes, and systems for control with respect to mitigating the potential for misrepresentation.

Oh, so they are going to do due diligence? Tanta doesn’t think so; she envisages a questionnaire. But that’s still progress of a sort.

Standard & Poor’s just drove a huge harpoon into the heart of the mortgage credit bubble, and it’s going to take a long time to clean up the mess once the beast finally dies.

S&P, one of the three main credit-rating agencies that served as enablers of the subprime-mortgage boom, announced Tuesday that it would lower its ratings on 612 bonds, a small portion of the mortgage-backed securities it had given its seal of approval to.

But the bigger news is that S&P isn’t going along with the charade anymore. S&P said it would change its methodology for rating hundreds of billions of dollars in residential-mortgage-backed securities. And it would review its ratings on hundreds of billions of dollars in the more complex collateralized debt obligations based on those subprime loans.

A lot of debt will be downgraded to junk status. A lot of that debt will have to be sold at fire-sale prices. A lot of pension funds and hedge funds that once thrived on the high returns they could get from investing in subprime junk will now lose a lot of money.

S&P’s announcement is a death warrant for the subprime industry. No longer will mortgage brokers be able to help buyers lie their way into a home. Fewer stressed homeowners will be able to refinance their mortgage, thus extending and exacerbating the housing bust.

“We do not foresee the poor performance abating,” S&P said.

Prices will fall, and foreclosures will rise. More mortgage fraud will be uncovered as the tide goes out.

And hedge funds will have to find another way to beat the market — if they survive this blow, that is.

Now that may sound terribly melodramatic, but consider this tidbit from (of all places) the UK’s Telegraph:

When creditors led by Merrill Lynch forced a fire-sale of assets, they inadvertently revealed that up to $2 trillion of debt linked to the crumbling US sub-prime and “Alt A” property market was falsely priced on books.Even A-rated securities fetched just 85pc of face value. B-grades fell off a cliff. The banks halted the sale before “price discovery” set off a wider chain-reaction.

“It was a cover-up,” says Charles Dumas, global strategist at Lombard Street Research. He believes the banks alone have $750bn in exposure. They may have to call in loans.

The reason I take this seriously is that I heard rumors after the Feb 27 global selloff, in which subprime related paper took a bit hit, that if the downtrend had continued much longer, the margin calls to hedge funds would have forced a larger wave of selling that would likely have damaged dealers.

The rest of the Telegraph piece is sobering reading:

Not even the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has a handle on the “opaque” instruments taking over world finance.

“Who now holds these risks, and can they manage them adequately? The honest answer is that we do not know,” it said.

Markets have been wobbly since the surge in yields on 10-year US Treasuries, the world’s benchmark price of money. Yields have jumped 55 basis points since early May on inflation scares, the steepest rise since 1994. It infects everything; hence that ugly “double top” on Wall Street and Morgan Stanley’s “triple sell signal” on equities.

Wobbles are turning to fear. Just $3bn of the $20bn junk bonds planned for issue last week were actually sold. Lenders are refusing “covenant-lite” deals for leveraged buy-outs, especially those with “toggles” that allow debtors to pay bills with fresh bonds. Carlyle, Arcelor, MISC, and US Food Services are all shelving plans to raise money. This is how a credit crunch starts.

“This is the big one: all investment portfolios will be shredded to ribbons,” said Albert Edwards, from Dresdner Kleinwort.

The BIS had warned days earlier that markets were febrile: “more risk-taking, more leverage, more funding, higher prices, more collateral, and in turn, more risk-taking. The danger with such endogenous market processes is that they can, indeed must, eventually go into reverse if the fundamentals have been over-priced. Such cycles have been seen many times in the past,” it said.

The last few months look like the final blow-off peak of an enormous credit balloon. Global M&A deals reached $2,278bn in the first half, up 50pc on a year. Corporate debt jumped $1,450bn, up 32pc. Private equity buy-outs reached $568.7bn, up 23pc. Collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) rose $251bn in the first quarter, double last year’s record rate.

Leveraged deals are running at 5.4 debt/cash flow ratio, an all-time high. As the BIS warns, this debt will prove a killer when the cycle turns. “The strategy depends on the availability of cheap funding,” it said.

Why has such excess happened? Because global liquidity flooded the bond markets in 2005, 2006, and early 2007, compressing yields to wafer-thin levels. It created an irresistible incentive to use debt.

What is the source of this liquidity? Take your pick. Goldman Sachs says oil exporters armed with $1,250bn in annual revenues have been the silent force, sinking wealth into bonds; China is recycling $1.3 trillion of reserves into global credit, a by-product of its policy to cap the yuan; Japan’s near-zero rates have spawned a “carry trade”, injecting $500bn of Japanese money into Anglo-Saxon bonds, and such; the Swiss franc carry trade has juiced Europe, financing property booms in the ex-Communist bloc. And, all the while, cheap Asian manufactures have doused inflation, masking the monetary bubble.

The deeper reason is the ultra-loose policy of the world’s central banks over a decade. They “fixed” the price of money too low in the 1990s, prevented a liquidation purge to clear the dotcom excesses, then kept rates too low again from 2003 to 2006. Belated tightening has yet to catch up.

Don’t blame capitalism. This is a 100pc-proof government-created monster. Bureaucrats (yes, Alan Greenspan) have distorted market signals, leading to the warped behaviour we see all around us.

As the BIS notes tartly in its warning on the nexus of excess, this blunder has official fingerprints all over it. “Behind each set of concerns lurks the common factor of highly accommodating financial conditions” it said.

Rebuking the Fed, it said Japan and Europe have turned sceptical of the orthodoxy that central banks can safely let asset booms run wild, merely stepping in afterwards to “clean-up”.

The strategy leads to serial bubbles, creates an addiction to easy money, and transfers wealth from savers to debtors, “sowing the seeds for more serious problems further ahead”.

If you think we are too clever now to let a full-blown slump occur, read the BIS report.

“Virtually nobody foresaw the Great Depression of the 1930s, or the crises which affected Japan and south-east Asia in the early and late 1990s. In fact, each downturn was preceded by a period of non-inflationary growth exuberant enough to lead many commentators to suggest that a ‘new era’ had arrived,” it said.

The subtext is that you bake slumps into the pie when you let credit booms run wild. You can put off the day of reckoning, as the Fed did in 2003, but not forever, and not without other costs.

So the oldest and most venerable global watchdog is worried enough to evoke the dangers of depression. It will not happen. Fed chief Ben Bernanke made his name studying depressions. He will slash rates to zero if necessary, and then – in his own words – drop cash from helicopters. But his solution is somebody else’s dollar crisis.

On it goes. Perhaps governments should simply stop trying to rig the price of money in the first place.

Applicable to just about any credit bubble/bust.

Optimists borrow money. But the REAL optimists lend it to them.

As anyone in the jobs market will tell you, the crash was well under way by the summer of 2007, when companies stopped looking for new staff – particularly temporary and contract staff, kicking the crash and depression into late 2007 or even 2008 is an outright lie

‘The bear credit market has begun.‘

YIKES! Oh wait, that was ten years ago. *wipes brow* Lack of indenting almost scared me out of my junk bonds.

Actually there has been a one-percent dip in high yield this month. Chart:

Credit spreads are about as low as they ever go. With journos and hedge fund honchos issuing dire warnings about the rumbling VIX volcano, the going gets bumpy now and then.

Nevertheless, it just don’t feel like the party’s quite over yet. Obama’s back, and health and wealth are just around the corner. :-)

Indent fixed, thanks. The tip-off for me was this:

This time is different.

I still miss Tanta, even though I never met her.

So do I.

Calculated Risk was what inspired me to pull out of enough things so I only lost 20% in the crash.

Very grateful.

CR and Housing Bubble Blog are the two places I turned when I was trying to figure out “Is the real estate market mad, or is it me?”

I’m a financial idiot, but I remember telling my better half that something about this is not right. When asked why, I told her the rental costs had mostly flatlined, but housing purchase costs were still soaring, but both almost always tracked together.

In the long term housing is housing whether you rent or buy. In the last two housing/stock bubbles, if I remember it right, the rents started to separate from housing purchases, and then whatever was the driving bubble deflated taking the other bubble down.

I kept seeing all these people saying buy, buy, it’ll never go down! This less than a decade from the last bubble and I was thinking am I crazy? Is it me? Or has most everyone else gone crazy? It was a scary thought. The idea that smart educated people would all exuberantly thunder over the cliff together.

So do I. I have the Tanta hoodies to prove it.

She was great. I think her posts are still archived at Calculated Risk – an excellent resource.

RIP, Tanta! You made a difference.

Edit cut off while in process. She was funny, snarky but understanding of human foibles and failures, right on target and eminently lucid. Loved reading her posts, and learned a lot even though I’d spent over 20 years in the business.

“Mater of public service”

A new accolade for you :)

This is a very important post and I encourage all newer, post-Crash commenters to read it.

NC came as near to owning this story as any venue can; an amazing achievement.

And this is the class of blog the Googles and Facebooks of this world would like to censor out of existence.

Unsurprisingly.

Thanks, great post…lifted this from the bloomberg story…”The securities, backed by everything from student loans to auto payments to mortgages, almost doubled to about $9 trillion outstanding since 2000, according to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.”…everyone should be given a robot that will work to pay off their debts? That 9 trillion is one serious empty calorie sugar high, now the diabetes sets in?

A brief personal anecdote. In 2006 my partner and I were doing brisk business selling and managing rental properties in the Oklahoma City/Norman metro area. Principally, our clients were Californians who wanted to “get in” on the property craze but were priced out of the West Coast. All of this came to an immediate halt, as Samil posted above, late spring 2007. Suddenly clients wanted to wait, had problems with price, felt they were “too leveraged”, or wanted/needed to sell at a well-above market price. Credit for these types of deal seemed harder to get and clients suddenly felt stressed.

By October, sales activity had come to a near halt and I was selling off chunks of my property management portfolio to exit the business…the DOW was at a record high in October and I felt that I was at risk of going broke. My takeaway is that no one, neither the mom and pop investors nor myself, understood the value of the assets or cost of money borrowed to acquire the assets. We all got drunk on the Kool-aid of easy money and had to face the economic hangover of 2008.

Something similar is happening today. Asset prices and disconnected from the incomes are end-users. Record stock market disconnected from fundamentals like earnings and profit. There is a unicorn craze and imminent massacre if Uber, Snapchat, and Blue Apron are front running tech. The metastasizing housing bubble along with the boom of precariat jobs. Something feels off.

What is the value of a stock when a central bank (with the ability to create money out of thin air) buys millions of shares as in the case of Apple and the Swiss National Bank? What is the value of the stock market overall?

If you go look at balance sheets of a good number of large cap stocks in the S&P500 you will notice that book value per share has been coming down while stock prices keep on increasing. Companies taking on debt to buy back shares and or increase dividends.

Time will tell how long the multiple expansion can last. Not many looking at fundamentals.

Here in Tucson, the housing bubble was starting to hiss air during Q3 2005. After years of tight inventory, the city was suddenly awash in “for sale” signs. Some of those signs stayed up for years.

Ditto for large portions of California. The real mystery to me wasn’t that the market tanked from 2007-2009, it was why it took so long to get there. The writing was on the wall from October 2005 throughout 2006 for anyone willing to look. 2007 wasn’t the beginning, it was just the beginning of public recognition. But the deniers didn’t even capitulate until late 2008.

Evidently most people prefer their blissful ignorance to last as long as possible, even when the truth is right before their eyes.

That’s Steven Eisman of Big Short fame who knew what he was talking about last time around. Wondering if his question to S&P means he made bets that prices might tank a little sooner….

This quote from that Telegraph piece brought a chuckle –

Sounds like the author must be ignorant of the revolving door between the public and private sectors. If Greenspan and his ilk aren’t the avatars of capitalism I don’t know who is. The Greenspans and Bernankes of the world aren’t going to do much that the Blankfeins and Dimons haven’t told them to do.

Anyhoo, great post!

Kinda in shock I was only one of 200 daily readers back then.

Yes…

Still have PTSD from it even tho my fund navigated it well

Subprime jitters were seen as early as May 2006. Bookstaber just released “Demon of our own Design” which proved prescient

Amaranth blew up on an overlevered energy bet Sept 2006

Bear blew out next spring, followed in Aug 2007 by the “quant quake” as market neutral funds liquidated equities to meet credit/illiquid calls

Aug 9 2007 was the end of the quant meltdown but calling it the “start” of the GFC is ludicrous

Before Bear Stearns announced the nearly total wipeout of the two funds, the expectation was ~90% recovery. The money markets’ exposure to similar assets was not widely understood outside of those markets; worse, the role of the money markets themselves in the functioning of the economy was barely appreciated by, for example, the equity markets. The meaning of counterfeit high-quality paper in the money markets is very different from say, a diversified bond fund, and this stuff had been sliced and diced into very short term paper; ratings were no longer credible, rates went crazy and the freeze started almost immediately. What was happening exploded received economic wisdom (“no market failures”; “equity markets are efficient”) but I’m not sure those lessons have been learned at all.

Thanks for the reminders.

“I gasped out loud in May 2007 when I saw Ben Bernanke declare that subprime was contained and estimated potential subprime losses at $50 billion. ”

Yep. I remember Bernanke giving testimony to a Congressional committee late summer 2007 ( reported WSJ) wherein he said there was no housing bubble, elimination of mortgage insurance for low down-payment loans was not a problem, and any problems were all contained. Alarm bells started going off in my head. At that point I started looking for better information about what was happening than I was getting from most publications. I found NakedCapitalism.

I too remember. This was, then as now, a great site for plain unvarnished information at a level of understanding far beyond the trade rags, not to mention the mainstream media.

Yves, you deserve three cheers and a big huzzah! Didn’t know how you did it then, don’t know how you keep it up now.

I vaguely recall reading Slate, somewhere around February 2007, where one the writers (economists?) had an article about a group selling stuff to the large public. The writer stated, with other examples, that this was typical behavior of an end-of-cycle thing: as there were no ‘smart’ clients left, ‘ordinary people’ were being marked as easy targets.

I was still learning at that time, so moved around CR, Krugman’s blog and several others, until somebody brought me to NC (I still recall – the reprint of Steve Keen’s ‘Roving Cavaliers of Credit), and never left.

Anyhow, I have always been convinced that the writing was on the wall in early 2007, and never understood the later dates.

If I read Bill Black correctly, the FBI had warned of systematic fraud in the mortgage market as early as ’04. This laid the foundation (pardon the pun) for the financial crisis. So someone knew things were getting out of hand well before ’07/’08. A real hat’s off to Yves and the crew, I have yet to find a site that offers the amount of information, insight and analysis as NakedCapitalism. Bravo and Cheers.