Yves here. It’s hard for me to see any merit in the Fed unwinding its balance sheet. If the Fed wants to intervene in particular ways, it has plenty of its famed tools for doing so. By contrast, selling off its assets will have unknown effects.

If the central bank does nothing, its assets will run off in time, admittedly quite a long period of time. The reasons for this move look to be political and aesthetic: the appearance of the Fed having such large holdings bothers some, particularly those of a conservative persuasion. But if you go back to 1980, the Fed’s balance sheet was about 20% of the size of the US banks’ total assets per McKinsey analyses. And banking lending back then was also a much higher percentage of total credit creation (securitization and the use of other off-balance-sheet vehicles have greatly reduced the importance of banks).

One argument might be that the Fed is holding so many Treasuries that traders have complained of “shortages”. Again, I don’t have much sympathy. The biggest use of Treasuries is as collateral for derivatives positions. Advanced economies, including the US, have financial systems that are so large that they are a negative for growth. In 2015, the IMF ascertained that the optimal size of a financial system relative to the economy was roughly that of Poland, implying that countries like the US would benefit greatly from cutting their banking sectors way down over time. Other studies have singled out the level of secondary market trading in advanced economies as one of the most unproductive activities. Thus more scarce Treasuries arguably help in a small way in reducing churn that feeds financiers to the detriment of the rest of us.

By Silvia Merler, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and before that, an Economic Analyst in DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Originally published at Bruegel

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) held short-term interest rates steady on September 20th and announced that starting from October 2017 the Fed will gradually shrink its balance sheet, which grew considerably in response to the Great Recession. We review economists’ views on this move.

Joseph Gagnon at PIIE thinks that the unexpected development was a further reduction in the median view of FOMC participants about where the short-term interest rate will settle in the long run. The Fed apparently endorses the view that the slowdowns in the growth rates of productivity and the working-age population have persistently lowered both the economy’s potential growth rate and the rate of return on investment. Shrinking the balance sheet will tighten financial conditions because it will increase the amount of long-term bonds in the market and thus push up their yields. Much of any increase is probably already priced into bond yields, given that this decision was telegraphed so clearly in advance. The 10-year Treasury yield rose only 2 basis points on September 20, but it has risen 58 basis points over the past 12 months, in part reflecting expectations of today’s decision. The FOMC continues to project another federal funds rate hike in December. However, Chair Janet Yellen made it clear in her press conference that many participants in the committee are troubled by the decline of measures of core inflation earlier this year. If data over the next three months do not show some evidence of inflation returning toward its target of 2 percent, as the FOMC currently expects, rate hikes are likely to be postponed.

Richard Clarida on Pimco Blog thinks there are intriguing clues from the dot plot, which shows the median FOMC participant is inclined to hike the fed funds rate by year-end 2017 and also has marked down her or his longer run dot to 2.75% (from 3% in the previous dot plot in June).

Clarida argues that the FOMC dot plot now clearly indicates that many on this committee expect that the Fed may have to overshoot the longer run neutral rate. This reflects the fact that the Fed’s statement of economic projections (SEP) shows U.S. unemployment falling to 4.1% over the next two years, well below the unchanged estimate of NAIRU of 4.6% (the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment). To keep projected U.S. inflation at 2% – and according to the SEP, the Fed expects to see 2% inflation by 2019 – the Fed’s models, and several of the dots, indicate this would call for a tighter-than-neutral policy rate. Each dot in the plot tells a story – but the eventual outcome is not yet written.

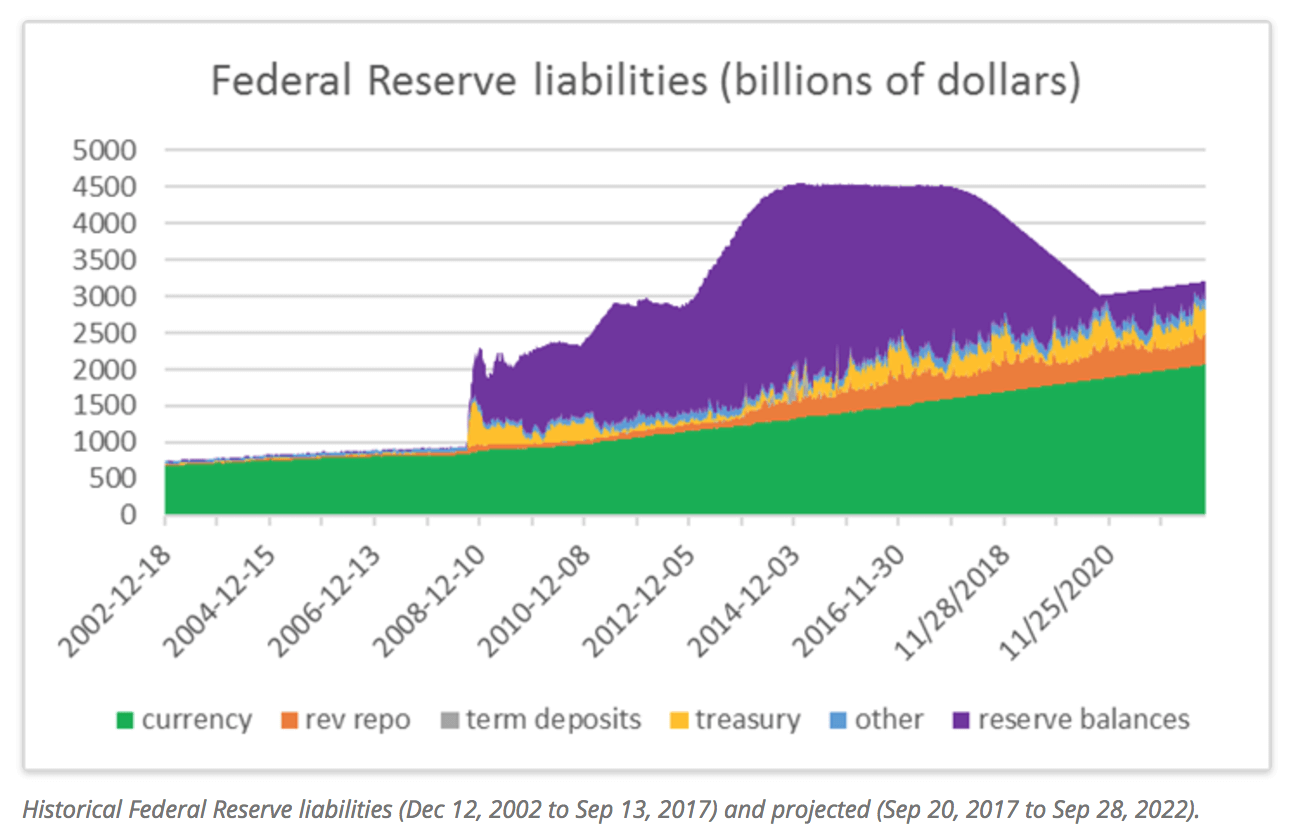

James Hamilton at Econbrowser thinks we may not have seen the end of balance sheet expansion. He created a mock-up of what the balance sheet would look like if the Fed reduced its holdings by the maximal amount at a smooth weekly rate and supposing that the Fed maintains the rate achieved by the end of 2018 through 2019 and the first three quarters of 2020. These projections assume the Fed will resume growing its balance sheet in 2020:Q4, and never let total assets fall below $3 trillion. The reason the Fed may go back to growing its balance sheet within three years comes from thinking about the liability side of its balance sheet. The big bulge in assets has mainly been financed by extra Federal Reserve deposits held by financial institutions, but several other liabilities are also significant– deposits held by the U.S. Treasury’s account with the Fed, deposits that get returned temporarily to the Fed through reverse repos, and currency held by the public.

Source: Econbrowser

A key feature of those last three is that under current Fed operating procedures these quantities are basically chosen outside the Fed. The reason that total liabilities have remained almost constant week-to-week for three years in the face of this volatility is that Fed deposits of financial institutions have acted as a big buffer, elastically growing or contracting in response to whatever happens at the Treasury or with reverse repos. In Hamilton’s simulation, if the Fed were to continue reducing its balance sheet through the end of 2020, the level of Fed deposits by financial institutions may not be enough to cover the plausible variation in other Fed liabilities. There are other changes the Fed may consider to its basic operating system, such as changing the way it conducts reverse repos, using temporary open-market operations to add or withdraw reserves as needed to offset changes in the Treasury balance, or moving to a true corridor system for controlling interest rates. The gradual pace of contracting the balance sheet gives the Fed a couple of years to sort out how it’s going to do that.

The Economist’s Free Exchange makes the case against shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet. A way of viewing QE is as an operation that changes the maturity profile of government debt. The best size for the Fed’s balance-sheet therefore depends on the best maturity profile for government debt, once the liabilities of the Fed and the Treasury have been combined. If money is more useful than Treasury bills, then the Fed performs a useful service by swapping one for the other. And there is literature showing that money is useful, in the sense that abundant bank reserves increase financial stability, because otherwise increased money demand i satisfied by the private sector with very short-term debt like asset-backed commercial paper. But the political power of worries about the Fed’s balance sheet will help determine the endpoint for the Fed’s balance-sheet. The Fed will need more assets than it did before the financial crisis, because of increased demand for currency, another central bank liability.Which system is used, and hence the ultimate size of the balance-sheet, is a decision that will probably be taken after President Donald Trump decides whether or not to reappoint Mrs Yellen as chair.

Philippe Waechter argues that the Fed normalises but does not become optimist. Janet Yellen has indicated that the hierarchy of monetary policy instruments is clear. The Fed is confident that the US economy has definitively overcome the crisis, but it is not optimist. The projection of the Fed funds rate in the long term is 2.75%, which suggests the absence of a rebound in productivity gains as well as the demographic shock that will affect the American economy in the long term. The normalisation is anyway a relative one, because nobody could imagine today to go back to the pre-crisis equilibrium. The crisis may be over, but that does not mean a renaissance: it’s rather the management of a long-lasting degraded situation.

Matthew Klein on the FT writes that the Fed’s forecasts imply the bank will deliberately tighten monetary policy to slow the US economy, possibly to the point of outright recession, by the early 2020s. The economy’s growth rate is expected to slow down by more than half a percentage point. Ideally, this would mean that the gap between actual and potential output will have gently closed by the end of 2020, but several FOMC members seem to think the US economy will already be growing by less than its potential as early as 2019 and that the jobless rate will continue to be well below its longer run level even by the end of 2020. Either the longer run forecast will be revised lower, or central bankers are expecting to push the unemployment rate up by perhaps as much as a full percentage point. The median forecast for the “longer run” Fed Funds rate is currently 2.75%, a new all-time low, but the really interesting issue is how this theoretical estimate of “neutral” fits with the forecasts for actual policy 2019 and 2020. Seven current members of the FOMC want the policy rate to be above 2.75% by the end of 2019, and five want it to be above 3%. Only one person thinks the “longer run” rate is above 3%. That means at least five out of the maximum of 19 policymakers want the Fed to be actively slowing the US economy by the end of 2019.

Tho Bishop at the Mises Institute thinks that while tapering has been priced in, there are still major questions left unanswered. One of the biggest questions going forward is who will step up to replace the Fed’s purchasing power in the US Securities market. In the past, the US has been able to count on China to purchase US debt. Even before the Trump administration threatened the country with sanctions, China was selling off Treasuries in order to help prop up its economy. With other nations also backing off from US debt, the hope is that investors will fill the gap. While the continued actions of the ECB, BOJ, and other central banks may make US debt more attractive in comparison, increased investments in bonds is likely to come at the expense of other assets. Bishop thinks that the noise of the Fed’s actions only serves to distract from the real issue, which is the continuing economic stagnation of the US economy. While Yellen continues to boast about modest employment gains, full-time employment remains lower than it was prior to the recession and the Fed itself — which is regularly overly-optimistic — doesn’t seem to have much faith in the future. It is now projecting long-term below 2%.

David Beckworth at Macro Musing argues that while most people know the arguments for and against shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet on purely economic terms, there are other political economy forces at work too. Writing in The Hill, Beckworth argues that the large-scale asset purchasing program, combined with the introduction of the Fed’s program to pay interest on excess reserves (IOER) to banks, effectively transformed the Fed from a standard central bank into one of the most profitable financial firms on the planet. The Fed has been earning relatively high interest on its expanded holdings and paying very low interest on short-term deposits from the banks as part of the IOER program.

Given the profitability, prestige and jobs created by maintaining the Fed’s large balance sheet, it will not be painless for the Fed to shrink it. The Fed’s main reason for doing so is that it believes a large balance sheet is no longer needed for stimulus reasons. Another reason is that some Fed officials worry about the footprint its large balance sheet has on the financial system. But the Fed may also be eager to unwind its balance sheet because of bad optics politically. Most of the increased liabilities have been in the form of banks’ excess reserves, which banks deposit at the Fed and earn interest on. That means foreigners and the U.S. banks bailed out during the crisis are getting most of the interest payments from the Fed. Only time will tell whether these reasons will provide enough incentive for the Fed to completely follow through.

The Fed will not sell anything, it will just start to allow its assets to run off. Anyway, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly what good QE did and it’s therefore hard to lose much sleep over its end…

In other words, “Giving the patient a boatload of opioids was a terrible idea to start with, therefore the doctors shouldn’t lose sleep about the effects of withdrawal”.

That logic works out dandy for the doctors; for the patient, it’s potentially lethal.

I didn’t mean to say it was a terrible idea, I meant that it didn’t do much. You can go with all the metaphors you want, there isn’t any clear proof otherwise (very open to be proven wrong though).

I did mean to say QE was a terrible idea. It abjectly failed in its stated goal of stimulating consumption/inflation in the real economy, while also blowing an asset bubble in the financial economy. More succinctly, the first prolongs misery by precluding recovery from affecting the bottom 90%, while the second creates more misery by stimulating speculation.

In view of this I’ll stick with my metaphor. QE was the wrong cure that did far more harm than good. But simply ending it without attending to the patient’s actual needs– the medicine the economy needs is fiscal stimulus to create jobs and boost aggregate demand– would be akin to cutting off an opioid patient cold turkey.

What in the actual hell is a central bank doing with a big balance sheet in the first place, they are supposed to offer liquidity in times of market stress to good credits that are otherwise solvent at high rates of interest. Period.

The very idea that they should hijack capitalism itself and have some kind of quadruple mandate that now includes both bank solvency and asset prices is the most dangerous form of financial insanity imaginable.

And who backstops these

hedge fundscentral banks, the Central Bank of Mars?If they stopped paying IOER it would be the same as tightening but that $2.5 trillion would likely find its way to people who actually need it, they’ll spend and we’ll see even more inflation, oh joy.

[on Fed’s return to austere measures, after HAL has killed the rest of the economy]

HAL: Look Janet, I can see you’re really upset about this. I honestly think you ought to sit down calmly, take a bank stress test, and think things over.

The real problem is that “When you have a hammer, everybody is wearing a nail-shaped hat.” The Fed wanted to boost the economy and really their only tools influence the total money supply. The problem is that wealth concentration in the US has reached a point where boosting the money supply does little to boost consumption, partly because debt levels are ALREADY unsustainable. So all this extra money did little to boost consumer spending. Of course that ALSO means that it has done little to create the sort of wage/price spiral that its detractors worry about. And yet the Fed governors STILL talk as if more money would boost the real economy at the hazard that it might kick off inflation. Their “model” is still based on an economy that resembles the current one not very much. In the current economy pumping more money seems to simply increase income inequality, because most of it is captured into the financial industry.

QE was just an asset swap, it didn’t increase the money supply no matter what they thought they were doing. It swapped interest bearing assets for non interest bearing assets (cash) so it didn’t boost the money supply, if anything it decreased it. Just like ZIRP didn’t increase the money supply because you can’t force people to take out loans when they don’t want and can’t afford to.

If they wanted to increase the money supply they could write off any of the things they bought. They should have bought and written off underwater mortgages.

ding ding ding! This IMO was the correct response to the GFC – write down all the debt, restructure the banks and kick out senior management. Rip the band-aid off, endure a brutal recession for a short period (instead of the slightly less painful but much longer version that we’re getting) and enjoy a much stronger and self-sustaining recovery where a lot more people could find gainful employment. Alas, we f#$%ed it up.

Recall “suicide banker” Hank Paulsen’s bait and switch with his scribbled napkin note saying he needed $700B today or else the fuse would be lit. Ransom received, it then took him just ten days to go from “we’ll use it to help homeowners” to “we’ll just gift it to banks and everything will be fine”.

Hank so reminded me of Billy, in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest.

…Kesey would have had plenty to say…as do his on the bus buds who remain today…

(though I’m not a fan of)….”I make mistakes it’s true – but I must make mistakes to do what I do…”

..his family suffered those mistakes…

Along these lines; Leverage Cycle, Credit Surfaces, Debt Forgiveness.

Lectures last night and tonight:

SFI – 2017 Ulam Lectures:

John Geanakoplos on Debt and its Discontents

https://youtu.be/oHfjSVJSLCI

https://youtu.be/ze_CFmMqWHg

..perhaps I misunderstood, but I believe geithner and obama met with bankers and offered “QE”…(or would you guys prefer to place all your “securities” on open market = perhaps 15% paper debt value??) Over 7 years several advantages appear exist…let alone obama payback to Wall $treet donors…

“Because most of it is captured into the financial industry.”

I like the phrase.

Last I looked at the mission statement of the Fed it was to facilitate full employment. It cannot do that. Full employment is only accomplished by the government when the private businesses don’t.

From the sound of it the Fed sees itself as running the world for Finance, Wall Street more than for the people that gave it a charter.

It is the stock buy backs & 80 percent of the banking having to do with real estate that creates a weak economic model for the US.

Leastways that is my perception. Far as the US we got by without the Fed and it didn’t work so there was not a depression.

I myself am fine with not having for the purposes of the US, the Fed.

If it is out to keep inflation low, and little else, for a shared institution, it may not be helping us and we need to cut it loose.

Yeah QE did do much, just not for the People who actually needed it. We all can call it whatever we want & argue about it until we’re blue in the face, the only thing the FED does is make the Rich richer. And they are running the playbook perfectly while we got “bread & circuses”.

…”it”…did this much:

https://www.thenation.com/article/why-fdic-insuring-jamie-dimons-mistakes/

@Frenchguy: You said, “It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what good QE did“.

Indeed, it’s VERY hard. If you look at total employment in the country as a function of time (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS), starting in Jan 2010 and going through today, it’s quite impossible to spot when each of the three QE programs started and ended. [The little “blip” in May of 2010? Short-term hires for the US Census.] When it comes to employment numbers, QE had no detectable effect. Unwinding it should be similarly undetectable.

Alas, the same cannot be said for asset prices. They rose sharply during QE, and it’s quite likely that they’ll fall during unwinding. Part of me is thrilled about this possibility, as falling housing prices would make housing cheaper, and a lot of people could afford their own homes for the first time ever. And falling stock prices would mainly impact the super-wealthy, and they’re already rich enough to ride it out.

The only real risk is if stockholders overreact during an unwinding-induced stock market decline and start demanding that companies lay off employees to reduce labor costs and push up P/E ratios. There’s some risk of real harm there.

‘Falling housing prices would make housing cheaper, and a lot of people could afford their own homes for the first time ever.‘

Quite so. But with the middle class having about two-thirds of its net worth tied up in primary residences, falling house prices would produce deflation psychology — a sharp pullback in consumption and a hike in the personal savings rate. Here in the Shoppers Paradise, it would feel like the end of the world.

Since the Fed’s PhD know-nothings haven’t the slightest clue from either theory or empirical evidence as to how large a central bank’s balance sheet needs to be, they should just repeg where they are. A sixth-grade maff class could figure this out.

I can’t compete with financial analysts but if home prices would come down, I think that is a good thing.

Young people today cannot even think of owning a home unless they are in the fortunate class, as homes and even rental properties go to the wealthy who then jack up the rents.

On another site a poster mentioned that Russia thinks about people. America should go back to doing that.

*The fortunate class*

I like that! It really focuses on the importance of Parental Selection at Birth in acquiring wealth

@Jim Haygood: Given the precipitous collapse in the US homeownership rate (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RHORUSQ156N) that we’ve seen over the past 13+ years, “repegging” housing prices at today’s inflated values strikes me as rather unjust. This country desperately need more affordable housing, and risking some “deflationary psychology” seems worth the risk to me.

I won’t dispute your assessment of the Fed’s “know nothings”, though… Year after year they’d predict 4% (or better) annual GDP growth, and year after year we’d get about half that. About the only thing they successfully stimulated was the growth in various income inequality metrics: http://www.newsweek.com/2013/12/13/two-numbers-rich-are-getting-richer-faster-244922.html.

In my opinion a big part of of the problem of affordable housing comes from the fact that they keep building large expensive houses instead of much smaller apartments that buyers could afford. But smaller and more affordable is not incentivized for developers, so it doesn’t happen.

I live in Uruguay and a three bedroom 2 bath apartment can be had in the capital city for $100,000. The size is about 700 square feet. Affordable.

…hmmmnnn….look where “treasuries (held) as (financial) collateral for derivatives” (Yves’ quote is wonderfully focused) by Wall $treet banks (become “holding companies”) have (derivatives) landed:

“JPMorgan Chase shrewdly parks virtually all of its vast derivatives holdings in its commercial bank subsidiary. In the event of a collapse, the bank can use its deposit base to pay off the derivatives, while leaving the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to reimburse depositors if their money runs out.

JPM is the world’s largest purveyor of derivatives. Its total contracts have a notional value of $72 trillion—and 99 percent of them are booked at its FDIC-insured bank.

Citigroup has nearly all of its $53 trillion in derivatives in its FDIC-insured bank; Goldman Sachs has $44 trillion parked at an FDIC-backed institution. After Bank of America purchased Merrill Lynch, BofA began transferring the securities firm’s derivatives to the FDIC-insured bank, which now holds $47 trillion in contracts. When Senators Sherrod Brown and Carl Levin, among others, complained that regulators’ acquiescence in these transfers contradicted Congressional instructions in the 2010 Dodd-Frank reform law, the Federal Reserve, the FDIC and the Treasury Department’s Office of the Comptroller of the Currency refused to answer their objections. This matter involves “confidential supervisory” and “proprietary business information,” the three agencies responded in unison.”

https://www.thenation.com/article/why-fdic-insuring-jamie-dimons-mistakes/

Fed balance sheet reduction by decreasing reinvestment of principal payments. $6B/mo increasing to $30B/mo in twelve months.

https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/treasury-rollover-faq.html

4T/30B/mo = 133.33mo

I recall Richard Fisher, at a conference after his retirement, saying to keep an eye on the rollovers as the rollovers are a form of stimulus themselves and that balance sheet normalization will still leave a significantly higher amount relative to historical norms.

Q∞ has inflated assets which are owned by the rich people, such as real estate, stocks but has done zilch to help the poor people. I’m waiting for these assets to start crashing. The stock market is already showing sigs of weakening.

I’m Fed up!

Exactly. It is very clear that the only thing that QE definitely did was create giant inflation in asset prices – real estate and stocks most obviously – which has exacerbated inequality at a ridiculous rate, more than anything else. Regardless of stated intentions, this makes QE look like a deliberate policy to advantage the investor class without regard to the general consequences. It is inconceivable that such an outcome of QE was not imagined and anticipated by the decision makers.

Yves – sounds like you are supportive of continuing the policy of QE. Do you not consider its undeniable and severe inequality-worsening effect the thing we should be most worried about?

I don’t believe she supports it, just thinks that, at this point, it’s best to let it “unwind” over the long term.

Probably better for preserving status quo stability to unwind over the long term, that is not hard to agree to. But that will only deepen the trends of dispossessing the lower classes. Sooner or later, things will come to a head – with or without slow unwinding – that’s what Im trying to drive at.

No one mentioned the DEBT with leverage and record MARGIN DEBT at NY Exchange1

we are back to 2007 and more in terms of housing bubble and global debt!

In 2008, they said ‘ No one saw this coming’

What about NOW?

…if they “crash”, it will be covered by FDIC (American people) to THIS degree:

https://www.thenation.com/article/why-fdic-insuring-jamie-dimons-mistakes/

Richard Fisher: QE gift to the rich and the quick

https://youtu.be/mH7_ODj2nLg

Kevin Warsh: QE reverse Robin Hood

https://youtu.be/mJU_c__E_6Y

I was under the impression that the Fed did the banks a favor by buying loads of sh*tty Mortgage Backed Securities.

Is this not the case?

Has all that stuff somehow become more valuable over time, or is the divestment going to amount to a garage-sale?

Is it assumed that the Fed’s customers are ‘sophisticated’, and thus the price will reflect the real quality of the ‘product’?

What I’m wondering is, is this simply the last step in erasing the evidence of our financial sector’s crimes.

If you were to look at our strengths in terms of what we produce, where we can’t be undersold by the likes of China and the rest, it’s all about real estate.

To keep the real estate bubble going was paramount, in warding off a great depression part deux, and so far so good, even at the cost of pushing the idea of home ownership even further away from what a good many can afford.

But nothing goes up forever, and at some point reality has to enter into the scheme, and if free money vis a vis QE is no longer, then we’re already on the downslope, no matter what the current value or demand is.

No, the bought only government guaranteed MBS and a very few non-guaranteed MBS that were AAA rated.

They took garbage MBS as collateral (“cash for trash”) for one of their lending facilities (I can’t recall the acronym now) but all the borrowers paid back in full.

Thank you, all this time, (while QE has been happening) I’ve been wondering about the amount of ‘Toxic Assets’ in the mix.

Fed balance sheet assets by class:

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/es_20170818_hutchinsbalancesheet1.png

“AAA rated” “securities” are guaranteed by govt-necessarily “bought back”…control accounting frauds as elucidated by Yves, Michael Hudson, WK Black, define those frauds, though media and govt. appear intend kick that can down the road…Iraq (war crimes) style…

Alan “Kamikaze” Greenspan on how not to do tightening.

http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/45089000/gif/_45089770_us_rates_oct08_226gr.gif

What have you forgotten Alan?

He’s forgotten the delays in the system.

There were delays while the teaser rate mortgages reset; the new mortgage repayments became unpayable; the defaults and other losses accumulated within the system until everything came crashing down in 2008.

The FED had tightened much too fast by not appreciating the delays in the system.

Greenspan was on a suicide mission; luckily he bailed out before his mistake became apparent.

…but it did “become apparent”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PWen53eqmJo

It is noteworthy that none of the economists who expressed their views took a contra-austerity view regarding fiscal policy alternatives such as infrastructure and other domestic spending fueling real economic growth and wage-driven, cost-push inflation.

Given the choppy overall downward trend in 2-year US Treasury bond prices since the Fed began reducing its QE purchases and then discontinued QE in late 2014, I expect interest rates will continue to rise absent policy measures to suppress them. Based on history, the slope of the rise could be rather abrupt.

But it’s a complex world of constantly moving parts: private sector debt levels, global money flows, swap lines, derivatives, prices of commodities including oil, current account balances, off-balance sheet legal obligations, government budget deficits, military and civil conflicts, business and credit cycles, effects of climate change, massive control frauds, changes in supranational structures, etc. In terms of global central banking, it’s also a multi-polar world, with continued QE and even large-scale purchases of corporate bonds and equities by other central banks since the Fed discontinued the policy in late 2014. Projected growth in reverse repo balances is interesting.

…interestingly bailouts proceeded 2007-2014 = number of years statute of limitations for much fraud…no accident methinks…

According to what I have been reading the world had become a Unitary Power, that we blew through the Multi Polar Power balance. It is probably true that the US in military terms, is a Unitary power.

The enforcement of the Petrodollar took a military action in and against Libya.

As Corporations and banks do challenge the Nations for power over what life is like for the majority they may have a multi polar power.

Financial Terrorism is not at all inhibited by the courts. What was done to Greece and is being done to Puerto Rico is aggressive economic warfare.

If I was an international attorney I’d be in international court, maybe the ICC? Fighting against aggressive financial terrorism where debts of nations in bonds would not be written down to realistic levels, appears called for.

You may be on to something with Finance as being multi polar, and replacing the threats to a nation being from where they get their money.

Big assets, or lots of them, is it so much more than treasuries that Treasuries are made weak with whatever debt is being sold?

I apologize for speaking twice in this thread. I am very interested in world power balance characteristics.

“Who will step up to replace the Fed’s purchasing power in the US Securities market?” (Bishop, in article): baby boomers’ need to increase savings, I believe, is what has driven the Fed’s money creation to be parked in the securities markets as opposed to consumption. When 10 year USTreasuries pay 2.5%, I need more savings to retire than at 5%… this will naturally correct when the same boomers are forced to sell down securities in order to pay living expenses and at that point we will see inflation, lower markets and possibly even the dreaded stagflation.

As we indicated, the big holders of Treasuries are banks for repo to secure derivatives positions, not individuals. People with retirement portfolios hold the overwhelming majority of their investments in higher risk assets.

Agreed that retirement portfolios/insurances don’t hold as many Treasuries as they would normally want (even more true in Euroland); but if yields go higher, there will be demand from retirees (who may need to sell other assets), and someone will be holding the losses on longer-term Treasuries. Financing spending from sales of securities will IMHO will boost nominal GDP and so the net effect of QE will have been to displace inflation from the 2010 decade to the 2020 decade. So Yellen is right to aim at prudential rises in short term rates…

The ECB still are ploughing on with austerity in Greece.

The IMF predicted Greek GDP would have recovered by 2015.

By 2015 it was down 27% and still falling.

What did our mainstream, neoclassical economists get wrong this time?

They weren’t looking at Greece’s private debt load.

It’s that old chestnut again, post this link to Mario ASAP.

Richard Koo explains (he explained it to the IMF, but the ECB weren’t receptive and it’s the ideologue problem again):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Thinking has moved on since we locked them in their ivory towers.

The financial instability they created has helped economists outside the mainstream work out what they were doing wrong.