A new study by academics at John Hopkins confirms one of our long-standing criticisms of private equity: that the general partners misrepresent fund values in ways that make them look more flattering to investors. We’ll discuss the findings of the paper by Jeff Hooke and Ken Yook (hat tip Eileen Appelbaum) in more detail below. But first we will turn to why its conclusions are important.

In virtually every other line of investing, money managers see dodgy accounting as a reason to hang tight to your wallet, or even consider putting on a short sale. Yet in private equity, as we’ve chronicled from time to time, limited partners, presumably following the lead of industry consultants who depend on private equity as a significant meal ticket, and the general partners, are touting a new justification for investing as its returns falter and cannot be defended on a risk-return basis.

We’ve seen this movie before, with hedge funds. As we chronicled in the early days of this site, in 2007, it was clear that at best hedge funds weren’t delivering manager outperformance, or “alpha”. But alpha was the only justification for paying hedge funds’ nosebleed level fees. But pension fund and endowment managers, remembering the glory days of hedge funds when many really did deliver superior results, defended their investments as providing “alternative beta,” meaning market exposures that were still useful to them by virtue of their portfolio impact. Hedge funds were supposedly not highly correlated with the other holdings and therefore were still useful as a hedge.

The wee problem with this argument is that the investors could have created this “alternative beta” on their own or via package products for a small fraction of what they were paying hedge fund managers.

And in a few years, even that premise became a crock. By 2011, hedge funds were increasingly correlated with the stock market, undermining the last-gasp justification. By 2014, CalPERS announced it was exiting hedge funds altogether. By early 2016, many other investors were cutting back on their hedge fund allocations.

Similar to the efforts to justify continuing investments in hedge funds despite falling returns, for private equity, the great new saving grace is that its returns appear to be less volatile than those of public stocks. Let us stress the “appear” part.

Why Investors Love Phony PE Valuations

Unlike most other types of investment, the unrealized investment in a private equity fund, meaning the companies it has bought and will eventually sell, are priced only by the general partner. There is no third party valuation. By contrast, hedge funds get monthly valuations from independent valuation firms. So the general partners get do what no Wall Street firm would allow to occur on its trading desk, which is have traders to mark their own positions.

The private equity industry does have an argument for this troubling “trust me” setup: that the cost of valuing portfolio companies by an independent party like Houlihan Lokey would be on the order of $30,000 per company. Multiply that by, say, 20 companies four times a year, and you’ve got $2.4 million in costs. On a $1 billion fund, that’s close to a 0.25% annual cost on the commitment amount, which would represent a meaningful drag on returns.

But here’s the flip side: If you allegedly can’t afford to have adequate investor protection, should you be investing in that strategy at all, particularly in light of the considerable latitude that general partners have in computing these estimates?

The dirty secret of these valuations is that jiggering key assumptions, like the discount rate, margins, revenue growth, reinvestment requirements, within ranges that are plausible, results in a very large range of possible values. It’s not uncommon to find that changing the assumptions would result in a valuation of ten times what you’d get using conservative assumptions.

The truth is the portfolio company valuations are nothing more than a general partner’s opinion.

And there is strong evidence that valuations are often phony, as in artificially high, in at least three circumstances:

When stock markets are in distress, as in during the financial crisis. Leverage is a double-edged sword. Borrowing amplifies gains and losses. But you curiously don’t see that in how private equity general partners value portfolio companies, When you see downdrafts in the stock market, which typically are the result of trouble in the real economy that hurts both private and public companies, you don’t see private equity valuations falling as much (on the whole) as stock prices. Instead, the long-established practice in private equity is that when stocks take a nosedive, general partners mark down the valuations of portfolio companies much less. That makes no sense, since in general, private equity firms are levered, and levered equity should fall further, not less, in price than stocks as a whole.*

Around the time of raising a new private equity fund. In a 2013 paper, How Fair are the Valuations of Private Equity Funds? Tim Jekinson, Miguel Sousa, and Rüdiger Stucke concluded that general partners goose their valuations around the time they are raising a new fund, based on data from the entire life of CalPERS’ investments. Those false higher prices make returns look better than they really are:

We find that valuations, and reported returns, are inflated during fundraising, with a gradual reversal once the follow-on fund has been closed. Third, we find that the performance figures reported by funds during fund-raising have little power to predict ultimate returns. This is especially true when performance is measured by IRR. Using public market equivalent measures increases predictability significantly. Our results show that investors should be extremely wary of basing investment decisions on the returns — especially IRRs — of the current fund.

Note that the abstract of the paper also confirms (but underplays) the first point we mentioned, that of understating price declines in weak equity markets, which they benignly call “smoothing.”

Late in the life of the fund. Despite its widespread use, IRR, as we’ve discussed at some length in previous posts, is a poor metric. It also happens to be particularly flattering to private equity. Moreover, its quirks lead investors to have even stronger incentives than they’d ordinarily have to monetize successful investments early in the life of the fund.

As a result, the companies that are left in a fund later in its life tend to be dogs. A common pattern is to report prices for these businesses at their historical valuation level, even though the general partner would have presumably have sold the company by then at that price if that really was the price (the returns would be better if, for instance, a company was sold for $400 million in year 6 rather than in year 9). So these companies are eventually sold, more often than not at a price lower than what they were carried at, with the general partner making plausible-sounding explanations as to why it made sense to sell at a loss versus the valuation.

None of this would be that bad if investors were duly skeptical and took steps to manage against these deficiencies. For instance, they could insist on much stronger rights to demand portfolio company valuations, and have five or ten percent of the companies valued every year, with the selection made on a random basis. Similarly, the Jenkinson paper points out early returns on funds, when measured in IRR, don’t do a good job of predicting eventual performance. Yet despite experts having recommended the use of public market equivalent as clearly superior to IRR, limited partners still prefer to use IRR.

So why don’t investors look at the valuations more skeptically? They view those phony smoothed valuations as a feature, not a bug. Private equity researcher Peter Morris called it “A triumph of accounting form over economic substance.”

One big reason is that when most financial markets are tanking, private equity looks less bad by virtue of under-reporing its price declines.

Back to the current post. The article by Jeff Hooke and Ken Yook, The Curious Year-to-Year Performance of Buyout Fund Returns: Another Mark-to-Market Problem? provides the expected through review of relevant literature (useful because it show more studies raising red flags about private equity valuations and smoothing than I have to confess I was aware of) and argues that a public-market proxy can supply a reliable estimate of private equity funds’ values. From its abstract:

Recent academic studies have raised doubts regarding the alpha of buyout fund returns against mimicking publicly traded portfolios, and buyout investors have sometimes responded that lower returns are offset by the funds’ lower volatility relative to public stocks. Regarding the volatility of such returns, several studies have used a cash-flow-only estimation (CFOE) approach to calculate risk, as an alternative to relying on (1) actual cash flows paid to limited partners and (2) the asset valuations of unsold investments as determined by buyout fund general partners. These studies have suggested that buyout funds’ reported return volatility is understated relative to times-series public market equity returns. This study uses a methodology other than CFOE to evaluate buyout fund return volatility. The authors use a publicly traded mimicking portfolio, adjusted for buyout-type leverage, to measure risk, and conclude that buyout fund returns are more volatile than public equity market returns.

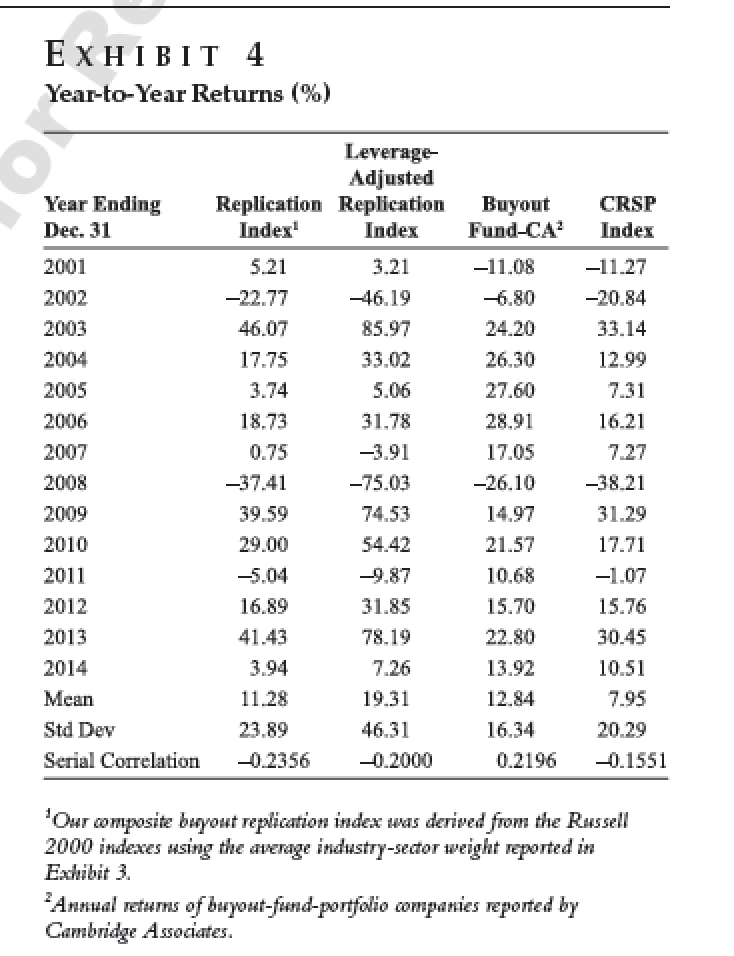

Here is the money chart, which we think speaks for itself:

From its conclusion:

Unlike investment pools that specialize in publicly traded securities, buyout funds determine the residual values, one-year returns, and the volatility of their fund returns, while having few checks and balances. In this study, we eliminate the possible bias of GPs in setting annual residual values for their funds by using a publicly traded replication index….and conclude buyout fund returns are more volatile than public equity market returns.

In contrast, the self-reported results of buyout funds indicate that their year-to-year equity returns are less volatile than those of the public stock market, despite the high leverage of buyout-fund-portfolio companies. These results contradict fundamental theories of finance, which stipulate that the use of leverage increases equity return volatility….

If this article’s conclusions are correct, future investors may have second thoughts about purchasing buyout funds instead of listed securities. Moreover, past buyout-fund investors may have been unfairly induced to place monies into these investment vehicles, in part through (1) faulty mark-to-market residual values, (2) improper year-to-year return estimates, or (3) inaccurate volatility calculations. Furthermore, many buyout fund return studies rely, by necessity, on residual value estimates of the fund GPs. If these estimates are inaccurate, the validity of these studies’ conclusions may be called into question.

The paper is very accessible and I encourage you to read it in full.

JPE-HookeNov

Page 8 of the paper:

Yup — it’s the financial equivalent of cold fusion in a jar: either an entropic miracle or a fraud.

The authors don’t expand on their finding of a positive 0.22 serial correlation in the buyout fund index, versus a negative -0.20 serial correlation in their leveraged replication index. But the discrepancy is redolent of “smoothed returns” that are partially untethered from public equities.

In his book No One Would Listen Henry Markopolos describes agonizing over how Bernie Madoff could produce 1% to 2% returns every month, in positive territory 96% of the time with almost no volatility. For months, he tried to reverse engineer Madoff’s stated strategy of using a basket of S&P 500 shares hedged with options. Markopolos concluded that it was impossible.

Likewise, trying to option-hedge the Russell 2000 — even with perfect foresight — to produce six straight years of low double-digit, largely market-insensitive returns from 2009 through 2014 is equally impossible.

Positive serial correlation is a giveaway that general partners are “banking” gains in blowout years such as 2009 (when the leveraged replication index popped 74%) both to backfill prior losses (such as 2008, when the leveraged replication index lost 75%, but PE funds fessed up to only a 26% loss) AND to boost weak subsequent years such as 2011, when the leveraged replication index lost 10% but PE funds claimed an implausible 11% gain.

This game works as long as their synthetic stream of smoothed returns doesn’t get too far out of line with underlying values. However, if the synthetic returns assume a steady double-digit uptrend, but private equity values only deliver (say) 5 percent annually over the next decade, some PE funds will be obliged to take surprise “big bath” writedowns as their wind-down date approaches.

Don’t say I didn’t warn y’all! :-)

Institutional investors are lemmings and its a cya scheme across the board – accounting firms, pe, lenders etc are all in on it. I had the benefit of seeing an annual valuation report for private cos year end 2015 exposed to the commodity industries. The accounting firm would selectively pull unflattering public comps and precedent M&A, alter the discount rate for the Dcf and game number of private co discounts to arrive at a much better value than would be expected.

Lenders like it toocause then the bankers don’t need to address any credit shortfall and pe loves it for obvious reasons and so do investors.

Just bizarre that if I can point to direct public peers that list 70pxt of value of equity then the private co should have lost something similar too. Who is to say whether mark to market is a full reflection of value but at that point in time and reflecting liquidity it is and should be consistent across assets regardless of public or private. People just like to put their head in the sand and not “feel” the downside which pe allows for.

Using public markets equivalents should be a no brainer no? Further to this, one would imagine with so much literature out there exposing the way LPs are being hoodwinked through these bogus valuations, the “trust us” narrative would have the legs knocked from under it. Or do the LPs have more money than sense…

It’s the illiquid “roach motel” aspect of PE which allows gamed valuations. Mutual funds can’t get away with phony valuations because shareholders can redeem daily at the stated value.

If partnership terms didn’t prohibit the transfer of limited partner interests, they could be traded on secondary markets just as public shares are, providing both price discovery and liquidity.

Presumably swaps could provide a workaround for restricted transferability, if there were a demand for such a product. It would be hilarious to watch the cockroaches scramble, as PE swaps instantly fall to a deep discount to stated value.

“… providing both liquidity and price discovery.” If there were a demand for such a product, I suspect the liquidity would be welcome, it’s the price discovery bit that will have people riled and worried.

There is limited buying and selling of LP interests. I didn’t mention that another proof of private equity overvaluation is that during the crisis, LP interests in funds were selling at ~60% of their official NAVs.

The problem with public market equivalent is you can’t do it accurately until a fund is fully liquidated. That + the time of getting the data to do the study means you are looking at funds 12 years or more old. Given that private equity returns have been falling since the early 2000s, having a dated view is flattering to the industry.

Otherwise, to try to study the value of PE funds, you dealing with funds that have a large portion of their total value in the private equity fund’s residual value. That means you are dealing with the valuation problems that the paper describes above.

Ahh ok, I see your point…

Hooke & Yook are forgetting: (4) Graft

Whether it’s Flexian revolving-door soft landings for money managers, private Elton John concerts at swanky “conferences” for nerdy civil servants, lavish political contributions to the elected officials entrusted with fund oversight, or the documented straight-up shoeboxes stuffed with cash delivered to fund executives, we live in a finance culture of pervasive grift and graft. Financier-ownership of the information media ensure that no one is accountable to the public or the beneficiaries. The whole system is rigged.

I have little doubt that Jim Haygood gets it right at the end of his comment: there’s going to be a “big bath” waiting for whoever is left holding the bag when these funds actually close-out and have to be honestly valued in liquidation. Then all this accounting smoke-and-mirrors will play out as “who-cudda-node” and “but my Board approved the decision” and beneficiaries will be blamed for having to audacity to have placed their trust in politicians. Not a nickel will be clawed back, because markets.