Yves here. No doubt, some readers will take issue with the logic of this post, in that they will see making investments to reduce exposure to the effects of climate change as a distraction from the more important task of getting greenhouse gas levels down. But the flip side is that relatively low cost measures that reduce overall societal costs free up free up more resources to address the underlying challenge. In other words, this doesn’t have to be seen as either/or.

This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration. Cross posted from Grist

In financial terms, 2017 was the worst year for natural disasters in American history, costing the country $306 billion. Scientists agree that hurricanes, floods, and fires are now turbo-charged by climate change, which the president and many top Republican leaders still refuse to acknowledge. But even while the federal government fails to address the root of the problem, there are ways to limit the damage from these increasingly frequent events — in property, and, more importantly, in human life.

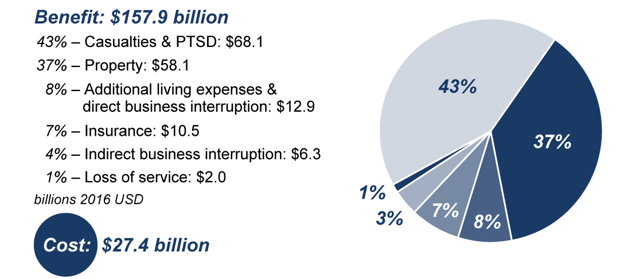

A new report from the National Institute of Building Sciences finds that for every dollar spent on federal grants aimed at improving disaster resilience, society saves six dollars. This return is higher than previously thought: A 2005 study by NIBS found that each dollar from these grants yielded four dollars in savings.

“A lot of things have happened since 2005,” said NIBS’s Ryan Colker, who contributed to the report. “Katrina, Sandy, and the increasing … frequency of disasters prompted us to look at what has changed.”

NIBS, a nonprofit group authorized by the U.S. Congress, took into account grants from FEMA, HUD, and the Economic Development Administration, whose staffs collaborated with NIBS to produce the report. $27 billion spent in mitigation grants over the past 23 years has yielded $158 billion in societal savings, they found. Many of the interventions the grants funded were simple, like installing hurricane shutters, replacing flammable roofs, and clearing vegetation close to a structure.

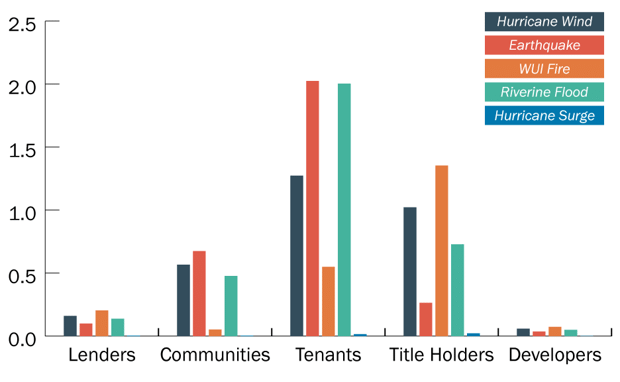

In addition to federal grants, the report also examines the financial benefits of private developers exceeding local building resilience standards. These interventions — such as elevating homes higher than required in flood-prone areas and building structures to be more rigid than required by seismic safety rules — yield four dollars in savings for every dollar spent. Unlocking these benefits is more difficult, however, since they are contingent on the decisions of private builders.

“As we continue to produce information about the benefits of resilience,” Colker said, “I think you can see an increased recognition from builders that people are willing to pay for this. There’s value associated with it.”

The study finds that developers accrue a small benefit from these long-term investments in disaster mitigation, but not nearly as much as tenants and property owners.

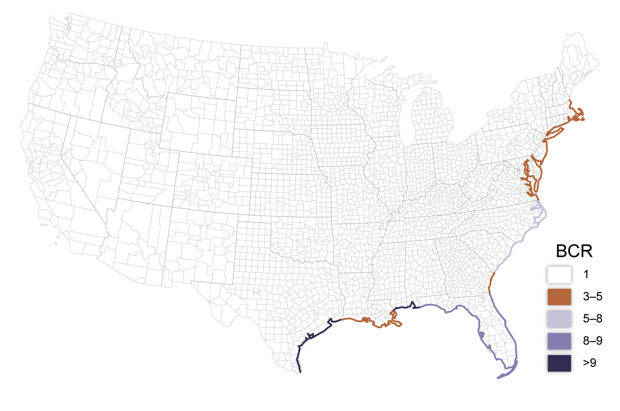

Some regions benefit disproportionately from both federal disaster-mitigation grants and better building practices. Stretches of the Gulf Coast, for instance, see a high benefit-cost ratio (BCR) on dollars spent to elevate buildings above the legally mandated height.

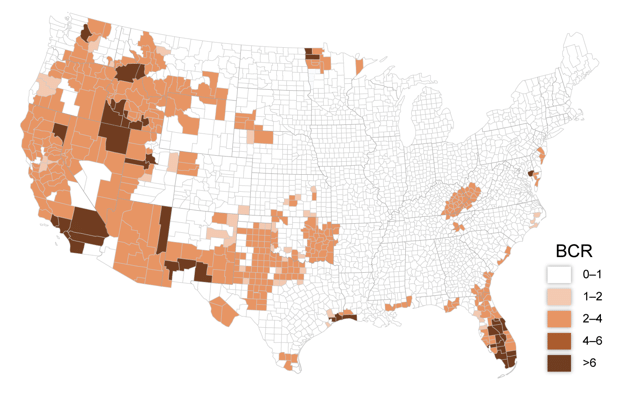

Large swaths of Southern California, Idaho, and (somewhat surprisingly) Florida derive particularly great benefits from investment in fire-mitigation efforts in new construction.

Ironically, the federal grants that this study reveals to be more effective than previously thought are on the chopping block in Trump’s first budget request. Specifically, FEMA’s pre-disaster mitigation grants would be cut in half; HUD’s Community Block Grant Program would be ended, and the EDA would be eliminated.

Meanwhile, FEMA’s Trump-appointed administrator, Brock Long, “is very much interested in increasing investment in mitigation up front,” according to Colker. It will be interesting to see how the administration’s intent to cut city and state grants of all kinds will square with Long’s position, which is now supported by empirical evidence from the NIBS report.

If the president and Congress are unwilling to act on climate change, at least FEMA has a proven strategy for mitigating its effects. That is, of course, if the agency has the money to implement it.

YS as you note, I take exception to the market treatment of AGW and side effects because the market mindset has zero ability to reconcile the data, outside narrow price dynamics and timelines.

This vantage for mitigating the impacts of Climate Disruption based on the Market and investment returns is almost comical. It reminds me of the studies on the ROI from each dollar spent for basic research in science or the ROI from little ventures like the race-to-the-moon. Who will make the investment and who will enjoy the return and of course who else would rather siphon off the money for other investments — like a few more F-37s — and who controls how investments are made?

I cringe reading statements like: “I think you can see an increased recognition from builders that people are willing to pay for this.” Who will benefit will depend on who can afford to pay for the resilience. How will the increased resilience be measured? People who can afford to pay may be willing to pay for resilience but how much resilience will they buy instead of a fancy stove or glossy bathroom fittings? And this: “elevating homes higher than required in flood-prone areas” leaves me wondering why are homes being built in flood-prone areas especially in light of what seem to be increasing risks of flooding in flood-prone areas. And the rates of increase are difficult to estimate but they seem seem to be accelerating.

Another further disturbing feature of this post is the implicit argument for improving building codes. This holds great potential for adding yet more complexity to the building codes. Building codes do need to be improved to increase the resilience of buildings but “improvements” to the building codes seem to operate like “improvements” to the tax codes — working to the greatest benefit of the large fixed interests and not the public.

Spending to mitigate the impacts of Climate Disruption by building better homes for people who can afford them seems like a strange approach in any case. It may pay a nice ROI but how does that ROI compare to the returns from other approaches to mitigation which in contrast to the proposals suggested in the post pay the greatest measure of their returns to the Common Good.

These decisions are subject to building codes. The are not the decisions of “private” builders.

This is a good thing, but it also serves as a reminder of how far down the rabbit hole we are at this point in time.

Adapting our civilizational infrastructure to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change should have started in earnest 30 years ago on a global scale. If, over those 30 years, we had systematically adopted building techniques designed to be more robust, way more efficient, less grandiose, modified our cities to be denser and have fully developed mass transit, pushed hard on renewable energy, etc, etc we would have had a strong chance of not slamming into the wall of decline at high speed.

We build some 1.5 million plus houses, apartments and commercial buildings in the US each year on average. In 30 years we would have built 45 million of them. Carbon emissions would be much lower and the effects of climate change less threatening. Of course, if we had been so inclined, we would also have reduced our population rather than grown it, we would have already eliminated most of our vehicle fleet, junked most of our airplanes, started the move away from the low lying coasts, stopped burning coal, stopped exploring for more oil and gas, the conversion to renewable energy would be far more advanced, etc.

Easy fixes are not on the table any more. That time has passed.

If we are to adapt and mitigate quickly enough to avoid drastic, violent, painful declines in global living standards, GDP, affluence, etc. then we need an immediate, full scale, global effort. And that is just not in the cards as anyone can see.

Ideas like Jacobson’s (Stanford 2009) on a 100% build out of renewables or Socolow/Pacalas(Princeston 2004) Climate Stabilization Wedges would both have been viable (big maybe here) 10-15 years ago. But even then they ran headlong into the reality that we do not have a command economy and the govt cannot dictate every detail of how people invest and decide to spend their money. Lacking that ability to order compliance these types of plans are dead on arrival. Capitalism and markets do not function in this type of situation and will provide no solution.

Where does that leave us?

To admit to the need for climate mitigation is to admit the existence of a global warming problem for which mitigation is being sought. This is an admission which the global warming deniers will never make, and will obstruct others from making to the bitter end.

Global warming reality-accepters need to figure out how to mitigate the future for global warming reality-accepters while withholding the benefits of mitigation from global warming deniers. Those who deny the need for mitigation have no right to enjoy any of mitigation’s benefits. Those who create the problem have no right to survive the effects of the problem they create.

“Those who create the problem have no right to survive the effects of the problem they create.”

Among ‘those’, of course, is about 99.999% of every American and every citizen of every affluent country on earth. Me and you included.

This being one of the main hurdles to making progress. Whether one is a dues paid member of the denier class (the black BAUers) or global warming reality-accepters (the green BAUers) essentially none of us are seriously working to fix this problem.

To accept the reality of climate change and its implications one has to then be willing to change completely their way of life and the philosophy/religion it is based upon. We have not yet seen evidence that any number of people are willing or capable of doing this.

The deniers just deny and go on about their business.

The ‘accepters’ pretend that their minuscule ‘green’ efforts are in some way sufficient to make a difference and this absolves them of living lifestyles essentially identical to those the deniers live.

Pots kettles and black.

no their lifestyles are neither here nor there, what it absolves them off is action to change the political system.

With this, I account four kinds of climate change-related investments: carbon-neutral energy alternatives, increasing energy efficiency, improving home resilience and buying insurance.

It seems to me that, of these, the one that meets the highest resistance to be implemented is energy efficiency while it almost certainly has the most possitive effects in the short-medium term. For instance, while spending in home resilience is good idea, why not conditioning releasing federal funds for housing resilience to improvements in energy efficiency? Once you have to reform a house, why not take care of both resilience and efficiency?

I believe that the main reason that makes energy efficiency less sexy (apart from utility companies rebuff), is that energy rates are flat or even down-sloped, following the typical “market rules”. Energy units are equally or less expensive for big spenders. Keeping bad incentives like this alive is what makes me pessimistic about the struggle against climate change.

How about “whatever” per kilowatt-hour for the first 100 kwhrs per month, a dollar per kilowatt-hour for the second 100 kwhrs used per month, two dollars per kilowatt-hour for the third hundred kwhrs used per month, and so on?

Making the price more punitive by progressives steps as usage increases?

See California electric rates for this sort of behavior.

OK. California.

Rates by sector (Oct17):

Residential: 15.37 c/kwh

Commercial: 16.98 c/kwh

Industrial: 14,61 c/kwh

Transportation: 9,34 c/kwh

Really not bad compared with other states and countries!

Yup. A big SUV with a “Save the Whales” sticker on it.

Climate scientists jetting to conferences all over the world. Haven’t they hear of skype?

Asking people to reduce their standard of living?

“Na Ga Happen”, in the words of our host. So on down we go.

Conservation and nuclear power are the only mathematical ways of mitigating CO2. No one likes either one.

If people really believed in global warming why do they build in Florida? I am told increased CO2 in the atmosphere is bad but no one does anything constructive. Why would you ever fly in a plane or drive a car?

Do the smart good people really believe in climate change?