We have yet another example of deficient governance and faddishness masquerading for good investment practices at CalPERS. Chief Investment Officer Ted Eliopoulos told Top1000Funds that CalPERS is thinking of investing in venture capital. We’ll explain long form why this is a lousy idea. From the story:

With more than $170 billion in equity exposure, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System is the biggest institutional sharemarket investor in the US. But chief investment officer Ted Eliopoulos says CalPERS is missing out on opportunities because private companies are waiting longer for their initial public offerings.

“What we see as an opening in the marketplace is how long private companies are staying private now,” Eliopoulos said in an interview at CalPERS’ semi-annual retreat meeting on January 16 in Petaluma, California….

“We think there is an opportunity for CalPERS to invest in private companies, perhaps at later stages of the venture cycle,” Eliopoulos said in the interview. “Companies that have gone through their first, second, third, fourth venture round but aren’t ready yet…to go public, that’s an opportunity.”

Help me. This is so wrong-headed I don’t know where to begin.

Companies staying private longer is bad for investors. Eliopoulos described the motivation as “more companies staying private.” But that doesn’t mean this behavior creates an investment opportunity. In fact, it prevents the monetization that investors need to realize returns. It might be different if these VC backed companies were growing up to throw off tons of free cash flow, but as far as we can tell, that is seldom if ever the case. As we wrote regarding Uber, a prime example of this behavior:

Kalanick had maintained he wanted Uber to stay private as long as possible. That may be a fad with some unicorns, but it’s not the way for a shareholder to maximize his net worth, so it’s a preference that raises questions about the founders’ ulterior motives. Needless to say, that desire put him at odds with his investors.

The reason late stage VC investments historically were attractive was that certain marquee investors would help validate the venture shortly before a planned IPO. The limited time between the investment and the IPO (and the investors’ reputation helping assure the IPO would be priced at a healthy premium to the last pre-IPO round) meant the odds of a quick profit were high.

With more companies staying private longer, these conditions aren’t operative.

As a result, late stage VC investors are often the dumbest of dumb money. Look at Uber. It did an investment round at an over $60 billion valuation with the Saudis, who are seen as pretty clueless. The round after that, the famed $68 or $69 billion valuation, depending on who reported it, was to the ultimate chumps, high net worth individuals. The financial disclosure for that fundraising was so inadequate that both JP Morgan and Deutsche Bank, hardly paragons of virtue, refused to present it to their clients even though this risked their standing in the management group for an Uber IPO.

Needless to say, JP Morgan and Deutsche are now looking like geniuses in keeping their high net worth investors well away from Uber, now that the latest round of funding from SoftBank has come in at a ~30% discount from the funding round they sat out. And insiders selling heavily into SoftBank’s bid is hardly a good sign.

Unicorn companies are universally engaging in what comes awfully close to valuation fraud. Readers might contend that I am giving a distorted picture in focusing on Uber, since it has managed to be an outlier in both how much money it raised as well as its level of management turmoil and deserved bad press. However, the need of other unicorns to preserve the illusion that they are increasing in value at an attractive rate has produced greatly exaggerated across the entire universe of unicorns where researchers could get the data about their fundraising terms.

This is critically important since CalPERS would almost certainly have bought into these bogus valuations, since investors who should know better, such as mutual funds, are reporting the same cooked-up numbers. Key sections from a 2017 post, which I am quoting at length:

We’ve written regularly about how private equity firms are widely acknowledged to lie about their portfolio company valuations….

But their go-go cousins in venture capital tell much bigger whoppers, and with much more visible companies.

A recent paper by Will Gornall of the Sauder School of Business and Ilya A. Strebulaev of Stanford Business School, with the understated title Squaring Venture Capital Valuations with Reality, deflates the myth of the widely-touted tech “unicorn”….

Gornall and Strebulaev obtained the needed valuation and financial structure information on 116 unicorns out of a universe of 200. So this is a sample big enough to make reasonable inferences, particularly given how dramatic the findings are. From the abstract:

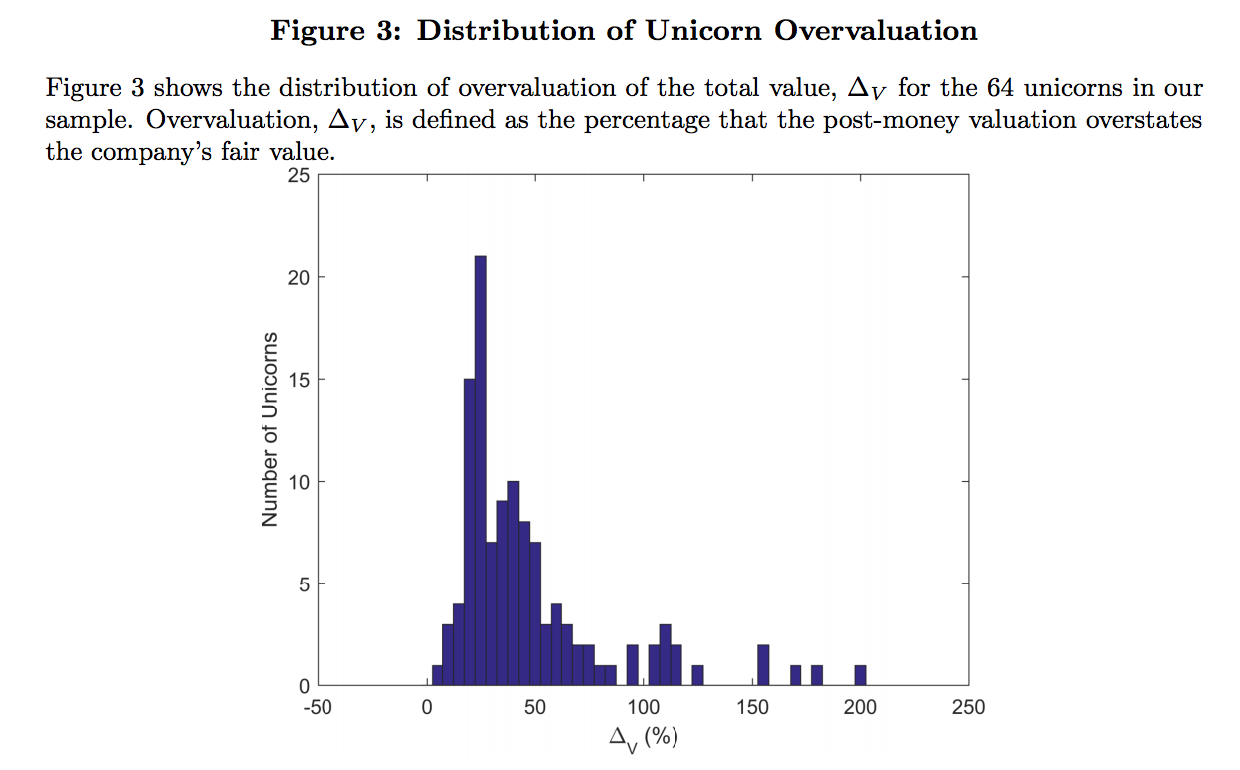

Using data from legal filings, we show that the average highly-valued venture capital-backed company reports a valuation 49% above its fair value, with common shares overvalued by 59%. In our sample of unicorns – companies with reported valuation above $1 billion – almost one half (53 out of 116) lose their unicorn status when their valuation is recalculated and 13 companies are overvalued by more than 100%.

Another deadly finding is peculiarly relegated to the detailed exposition: “All unicorns are overvalued”:

The average (median) post-money value of the unicorns in the sample is $3.5 billion ($1.6 billion), while the corresponding average (median) fair value implied by the model is only $2.7 billion ($1.1 billion). This results in a 48% (36%) overvaluation for the average (median) unicorn. Common shares even more overvalued, with the average (median) overvaluation of 55% (37%).

How can there be such a yawning chasm between venture capitalist hype and proper valuation?

By virtue of the financiers’ love for complexity, plus the fact that these companies have been private for so long, they don’t have “equity” in the way the business press or lay investors think of it, as in common stock and maybe some preferred stock. They have oodles of classes of equity with all kinds of idiosyncratic rights. From the paper:

VC-backed companies typically create a new class of equity every 12 to 24 months when they raise money. The average unicorn in our sample has eight classes, with different classes owned by the founders, employees, VC funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and strategic investors…

Deciphering the financial structure of these companies is difficult for two reasons. First, the shares they issue are profoundly different from the debt, common stock, and preferred equity securities that are commonly traded in financial markets. Instead, investors in these companies are given convertible preferred shares that have both downside protection (via seniority) and upside potential (via an option to convert into common shares). Second, shares issued to investors differ substantially not just between companies but between the different financing rounds of a single company, with different share classes generally having different cash flow and control rights.

Determining cash flow rights in downside scenarios is critical to much of corporate finance, and the different classes of shares issued by VC-backed companies generally have dramatically different payoffs in downside scenarios. Specifically, each class has a different guaranteed return, and those returns are ordered into a seniority ranking, with common shares (typically held by founders and employees, either as shares or stock options) being junior to preferred shares and with preferred shares that were issued early frequently junior to preferred shares issued more recently.

The way the VCs mislead the press and the general public is how that they assign a valuation after each round of fund-raising assuming all classes of equity have the same value….

And the paper confirms that just as in private equity, where everyone knows valuations are often sus but no one challenges them because the path of better bonuses and PR lies with playing along, so to VC investors who presumably do know better report these bogus figures to their limited partners:

Conversations with several large LPs indicate that VC funds follow the same practice and mark their holdings up to the most recent round. Even within the VC industry, many people treat post-money valuations as the fair value of the company.

And there are even more cute tricks VCs can and do play. For instance, companies can show rising valuations if they give enough goodies, meaning preferential treatment, to the latest round of funding, when a proper “post money” valuation would show that round lowered the “common shareholder” computation….

Let’s stop for a second. It isn’t just business reporters, who are typically captured and don’t have enough in the way of finance chops to challenge Silicon Valley Masters of the Universe, even if they think they are on to something. Investors like Fidelity and T.Rowe Price that are investing in some of these companies on behalf of retail mutual funds have been passively accepting these bogus valuation methods. Any fiduciaries, now that this practice has been outed, need to demand proper valuations or they will be violating their fiduciary duty by relying on egregiously incorrect valuations and being unable to make prudent decisions. And on top of that, some heads need to roll.

Public pension funds have generally avoided venture capital because they can’t deploy enough funds to make a difference even if they did well. Eliopoulos may fantasize that he can put enough money to work by focusing on later-stage, presumably bigger companies. But the law of large numbers alone works against CalPERS: large investment is never going to have the upside of a successful early-stage investment. Moreover, CalPERS’ own experts, like Harvard professor Josh Lerner, have shown that venture funds are even more skewed than those of private equity. The outperformance of the very top funds (top 10 percentile) is high, while median returns aren’t worth the bother. And here we observe the same fallacy we’ve seen before: that talking yourself into the proposition that you can pick the winners is yet another version of the thinking you can be the Warren Buffett of institutional investing. Most public pension funds reject that idea in all other asset classes and stick to indexing, yet perversely are seduced into behaving differently in the highest fee investment strategies.

The article does point out that CalPERS’ track record in VC isn’t encouraging (CalPERS is running off a legacy portfolio):

Venture funds make up just $1 billion of the system’s private equity portfolio.

They have also performed poorly. On a five-year annualised basis, ending June 30, 2017, they have returned 4.7 per cent, compared with the private equity portfolio’s overall 11.5 per cent for the same time period, CalPERS statistics show.

And as the point above, about unicorn overvaluation demonstrates, CalPERS looks to be preparing to invest in way that guarantees that its role will be to prop up phony valuations. Elioupoulos appears to have missed the fact that his preferred strategy would have him heavily, if not entirely, exposed to companies where the average overvaluation is 49%. This strategy would seem to be putting a target on the back of CalPERS board for litigation over breaches of fiduciary duty.

Some board members have bad incentives to promote investing in venture capital companies. The Treasurer and Controller are both elected officials. That means among other things, they need to raise money every four years to campaign for re-election or to seek another office.

CalPERS has reasonably good systems in place to prevent board members from lobbying to have CalPERS put money in particular pet funds. However, both the Treasurer and Controller, who carry more clout than other board members, have incentives for CalPERS to invest in venture capital whether or not it is good for beneficiaries. Right now, they are not perceived to have much of a connection to Silicon Valley. Having CalPERS invest in venture capital would be certain to get them invited to panels and other events which would give them face time with big-ticket donors.

Eliopoulos has slapped the board in the face. The board is finding out about this scheme in the press, as opposed to in a briefing. The top1000Fundsarticle mentions that it interviewed Eilopoulos at a board offsite meeting in which the board had a panel on innovation at which three investors spoke. What it does not mention is that the panel was a complete waste of the board’s time and bore no relationship whatsoever to informing them about how to invest. The three panelists gave war stories about what great guys they were, the sort of fare that would at most be suitable for MBA recruiting.

There was an ad hoc effort to pitch the attractiveness of VC to CalPERS in response to a line of questioning by Eliopoulos after the presentations, but it was the sort of superficial boosterism you can readily find in the trade press. And the only gap in the market that a panelist identified, the lack of early-stage funding, was implicitly rejected by Eliopoulos in his interview.

The lack of relevance is obvious when at the end, board president Priya Mathur asks asking about e-waste (at 1:26:15), a topic the speakers clearly aren’t prepared to address (notice the very long silence). No other board member poses a query.

Similarly, there’s not a single item in recent closed session agenda items related to venture capital, even assuming that a policy change of this sort could be permissibly relegated to private discussion under the state’s open meeting law, Bagely-Keene. So it looks as if the board is finding out about possible major strategy changes after the press. That should be completely unacceptable in any well-run organization.

However, since good governance seems to be an afterthought at CalPERS, it should not be surprising to have Elioupoulos demonstrate that board oversight is an empty letter.

Reading this, my first thought was that Silicon Valley would be loving this idea. I read that last year funding for new companies was getting to be a problem. Sure enough, a quick look came up with a story at http://www.businessinsider.com/early-stage-funding-for-startups-in-silicon-valley-stalls-2017-8?IR=T mentioning that seed-stage financing has been sliding for the last two years. Maybe this is where CalPERS thinks that it can go chasing the fast bucks. Can you do things fast and break things in accounting and financing without problems arising down the track?

If you go back to the top of the post, Eliopoulos rules early stage investments out. He wants to invest really late…gah! So you have limited upside at best and no liquidity. What’s to like?

Look at much ballyhooed AirBnB. Announced Friday it is putting off its IPO due to its finance chief quitting. That is a big red flag.

“Later stages of the venture cycle.” Is that when outcomes are surer, prices higher, rates of return lower, and the fees just as high?

Is fear of accountability what stops one of the largest pension funds in the world from doing its research, analysis and investing in-house? Its costs would be a small fraction of those it incurs in paying PE firms and venture capitalists. Transparency would be greater. It could pay near scale, but provide fabulously better working conditions than those prevalent in NYC, and still have a line of talented applicants (residents, voters and would be public employees) stretching from Sacramento to Silicon Valley.

Simple management incompetence seems to be an inadequate explanation. Other options include regulatory capture and belief in the neoliberal conviction that government should never do anything the “market” is willing to do, regardless of cost. Then there’s the possibility of outright corruption, such as some persons crudely redirecting a portion of the public trough to their Wall Street cronies.

Knowing more about the hurdles would help in getting over them. Many thanks for so closely following this story, because what’s bad for California is bad for America.

“[Private equity’s] go-go cousins in venture capital tell much bigger whoppers, and with much more risible [sic] companies.” — Yves Smith, slightly misquoted

If CalPERS is looking to hike equity returns, particularly in down cycles, the answer is literally under their noses: Big Tobacco.

With an eerily precise reverse Midas touch, CalPERS elected to bail from tobacco equities in the year 2000. Since then, the benchmark S&P 500 index has literally been whipped senseless by my Big Tobacco index, currently composed of Altria, Philip Morris, British Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco and Japan Tobacco [hat tip Brenda Alexander of Centers for Disease Control].

After 17 years the score is 19.00% compounded annual return for the quasi-gov sponsored Big Tobacco cartel, versus a pitiful 6.64% CAGR for the blue chip S&P 500. This chart don’t lie:

It’s the cost of being Californian, as it were. SAD!

There’s a job opening and the CDC.

Eliopoulos described the motivation as “more companies staying private.” But that doesn’t mean this behavior creates an investment opportunity. In fact, it prevents the monetization that investors need to realize returns. It might be different if these VC backed companies were growing up to throw off tons of free cash flow, but as far as we can tell, that is seldom if ever the case.

Paging Max Bialystock…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGdY4jfhKRM