Yves here. But Trump wants the headlines above all!

By Stefan Legge, Senior Researcher and Lecturer in Economics, University of St.Gallen, Piotr Lukaszuk, PhD Candidate, University of St.Gallen, and Simon Evenett, Professor of International Trade, University of St. Gallen. Originally published at VoxEU

While the Trump administration’s proposed tariff increases on Chinese imports have grabbed the headlines, few realise that other trading partners have also raised tariffs on Chinese trade. This column examines the effects of the EU removing China from its General System of Preferences in 2012. As a result of the move, $242 billion worth of EU imports from China were subject to higher tariffs, raising EU customs revenue by an estimated $4 billion.

Trade policy is grabbing the headlines to a degree not seen for years. US President Trump announced possible tariff increases on Chinese imports totalling $160 billion (Keynes and Bown 2018). However, few realise that other trading partners have raised tariffs on Chinese trade as well. Findings by the Global Trade Alert document a sharp increase in the share of Chinese exports facing tariff increases from 2014, predating the election of President Trump (Evenett and Fritz 2017: 64). Assessments of trade policy dynamics can be skewed by loud and transparent policy changes while hidden forms of policy intervention go unremarked.

In this column, we document two observations that have been neglected in the current debate. First, the EU raised tariffs on products from China between 2013 and 2015 when it removed the country from the General System of Preferences (GSP). Second, the EU might face a conflict of interest with respect to lower tariffs since customs duties constitute a sizeable share of the overall EU budget. Following our estimates, the removal of China from the GSP resulted in about $4 billion of additional customs revenue. This is substantial if we compare it, for example, to the cost of Brexit which amounts to the UK’s net contribution of roughly $12 billion in 2016.

Promoting China and Charging Higher Tariffs

To understand how the EU increased tariffs on Chinese products, first we recall that members of the WTO agreed to a most-favoured nation (MFN) principle. Simply put, this principle states that whatever tariff schedule a country determines applies to all WTO members. Hence, the EU cannot charge higher tariffs on goods, for example, from China than from the US. The two permitted departures from this principle are free trade agreements (FTA) and the General System of Preferences (GSP). The latter is a formal system of exemption from the general rules of the WTO to lower tariffs for poor countries, without also reducing tariffs for rich countries. Importantly, each country unilaterally decides which countries and products can benefit from GSP – with other countries and products facing MFN tariff rates.

In the case of the EU, in 2013 China qualified for GSP with about 60% of its exports to the EU benefitting from lower tariffs. However, in December 2012 the EU announced the removal of GSP benefits for Chinese products in most sectors starting from 1 January 2014, as they were deemed competitive on the European market. Moreover, China was removed entirely from the list of GSP beneficiaries in the following year as it no longer satisfied the condition of being classified by the World Bank as a lower-middle-income country for three consecutive years (Art. 4.1(a) of the EU regulation 978/2012).1As a result, Chinese exports to the EU were then subject to higher MFN duties.

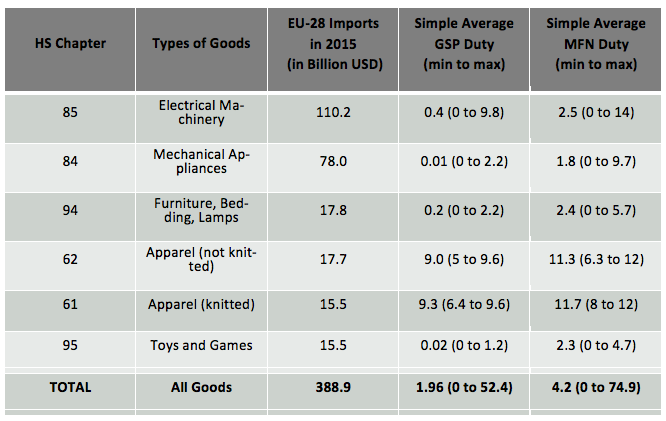

Descriptive statistics show that EU MFN duties were on average 4.2% in 2017. As for the EU GSP schedule, the average is given by 1.96%. It should be noted that over 98% of EU imports from China face MFN tariff rates below tariff peaks, that is, below 15%. In terms of tariff lines, only 102 out of 4,626 products exported by China (at the 6-digit HS code level) face such tariff peaks. Compared to the 25% tariff rates recently announced by the Trump administration for over 1,300 tariff lines, the EU’s move on China was much smaller – only 17 MFN tariff lines are equal to or above 25% (affected products are seafood, wine, and tobacco).

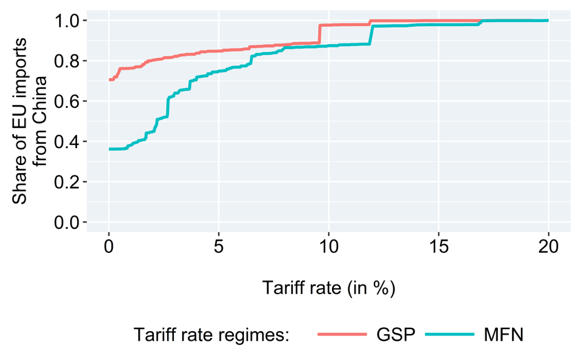

Figure 1 Accumulated EU Imports from China for GSP and MFN

In Figure 1, we show cumulative EU imports from China on the vertical axis. The figure shows that under GSP about 70% of imports were duty-free, while under MFN only 38% face a zero tariff. To further illustrate the difference between GSP and MFN as well as which sectors are most relevant in the bilateral trade, we show GSP and MFN duties in Table 1 for the industries with the largest EU imports from China.

Table 1 GSP and MFN tariffs for the EU’s largest imports from China

When restricting the data set to products (6-digit HS codes) with more than $100 million worth of EU imports from China, we find large tariff increases of up to 12 percentage points for video recording or reproducing apparatus, ball bearings, or parts of ball or roller bearings. Particularly noteworthy is the increase from zero to 6.5% for the $2.5 billion worth of articles of plastics (code 392690). In total, there are 480 products with more than $100 million and 34 products with more than $1 billion worth of imports that faced a tariff increase.

Overall, based on 2015 data, $242 billion of EU imports from China faced a tariff increase. This quiet tariff increase exceeds the scale of President Trump’s far more public threat to raise tariffs on $160 billion of Chinese imports.

Raising Revenue for the EU Budget

We reckon that the removal of China from the list of GSP-qualified countries had a significant fiscal effect.

Lacking actual tariff revenue data, we use tariff rates reported by the WTO combined with import values from UN Comtrade to estimate how much the EU collected in import duties from Chinese products. The dataset used for this analysis covers about 4,600 products (6-digit HS codes) for which we know the import value as well as the MFN and GSP ad valorem tariff.2Given that EU imports from China are stable in the years 2011 to 2016 at around $400 billion, we concentrate on import data from 2013 – the last year before Chinese imports were affected by the GSP withdrawal.

Using this dataset and average ad valorem duties, we calculate that the EU would have collected $6.1 billion if all imported Chinese products benefitted from available lower GSP tariffs and about $12.9 billion if the MFN schedule applied to all imports. Using minimum and maximum duties within 6-digit HS codes, we find a lower and upper bound of GSP customs revenue of $5.5 and 6.8 billion, while for MFN the revenue is between $11.1 and $14.8 billion. The estimated effect of removing China from the GSP of $6.8 billion (or between $4.3 and $9.3 billion) likely overstates the true effect. Rules-of-origin might have prevented utilising GSP so that reduced tariff rates are applied to only a fraction of imports. Nilsson (2011) finds that about 81.6% of EU imports from GSP-eligible countries utilised the GSP, while Keck and Lendle (2012) document a utilisation rate of 63% for imports from China.

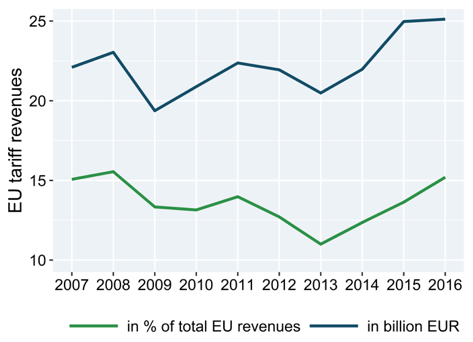

Taking into account these qualifications, how important was the removal of China from the GSP for the EU budget? In 2016, total EU revenue was €132.2 billion, of which customs duties accounted for 15.2%, or €20.1 billion. While tariff revenue is relatively small for rich countries today, the EU is more dependent on such revenue. For a comparison, customs and other import duties as percent of tax revenue are about 1.9% in the US. Typically, the poorer a country, the higher this share. The EU’s share of 15.2% aligns it with developing countries like Cambodia or Burkina Faso.3Notably, EU import duties are collected by member states, which keep 20% to cover administrative costs and pass 80% on to the EU.4Figure 2 shows a sizeable increase in total EU customs revenue when China was removed from the GSP.

Figure 2 Total customs revenue collected by the EU between 2007 and 2016

When interpreting the 2013 to 2015 increase in tariff revenue from about €20 to €25 billion, one must examine whether other changes in the EU’s trade policy played a major role. To our knowledge this was not the case since the EU-Korea free trade agreement came into force in January 2015 but had been provisionally in effect since July 2011. Taking this into account and assuming a 70% utilisation of GSP, the switch from GSP to MFN for imports from China raised about $4 billion for the EU budget.

Looking forward, the contribution of customs revenue to the EU’s budget may reduce the bloc’s incentive to liberalise trade, especially in light of revenue losses following Brexit. The March 2018 recommendation by the European Commission to impose an “interim” tax on the revenues of foreign internet giants is another warning of a growing commercial policy-budget nexus. With a “suggested” tax rate of 3%, the Commission expects this imposition to raise €5 billion euros from foreign companies.5Yet another reason to expect a less open EU trade policy in the years to come.

Endnotes

[1] On 20 November 2012, the EU’s GSP reform came into force. It reduced the number of GSP beneficiaries to about 80 countries, while expanding the number of affected tariff lines (regulation 978/2012). Shortly after, the Commission announced regulation 1213/2012in which it reduced the number of country-specific sectors eligible for GSP. China was the country mostly affected by these changes coming into force on 1 January 2014. Finally, China was fully removed from the list of GSP-eligible countries by regulation 1421/2013on 1 January 2015.

[2] We exclude tariff lines (i.e. 6-digit HS codes) for which duties are not ad-valorem. This constitutes 136 commodities which account for less than 1 percent of all EU imports from China.

[3] Data from the World Bank on Customs and other import duties (% of tax revenue) to be found here.

[4] The Official Journal of the European Union, published on June 6, 2014 states that “Member States are to retain, by way of collection costs, 20 % of the amounts collected by them”. It can be found here.

[5] For details see https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/company-tax/fair-taxation-digital-economy_en

See original post for references

The Chinese government has a fundamental existential crisis that they have 20 years to solve.

They have as many 55-70 year olds as 1-15 year olds and they have almost twice as many 45-49 year olds as 0-4 year olds as of 2015. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_China#/media/File:Population_pyramid_of_China_2015.png

So they are demographically at peak productivity now which can last for another 20 years. After that, they have far fewer people to move into the work force to support a growing elderly population. so they are in a race to get wealthy before they get old. If the government is not successful at this, then the social order will likely become social disorder and the government would fall, probably in an unpleasant way.

China does not have a history of successful immigration to fill demographic gaps, unlike the US and Canada. Europe is currently trying to do that but it is causing large social tension, resulting in things like Brexit.

Everything that the Chinese is negotiating is stared at through this lens. Meanwhile our politicians struggle to have a 2-year perspective.

This is just gonna help them out more when automation comes into play.

Maybe this is what their Made in China 2025 policy is all about. To put the emphasis on quality over quantity to not only compete but also to use a smaller work force to boot.

Given that EU imports from China are stable in the years 2011 to 2016 at around $400 billion

Interesting. I would have thought the increase in tariff would have reduced imports and made in-sourcing more attractive. Perhaps it did and maybe the growth in imports from China was less than it would have been otherwise? I guess one could compare to growth in imports in other countries, looking at their imports from China over the same period.

But let’s assume that the growth was the same (i.e. stable) either way. I wonder if this gets back to the transcript from Micheal Hudson that was posted last week: https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2018/04/hudson-report-trump-know-anything-trade.html . Prof Hudson identified that entities in China need to import currency in order to repatriate profits back to the home country. In that particular thread, the conversation was about US corporations in China repatriating profits back to the US. But presumably the same logic applies to EU corporations operating in China as well.

In which case, those exports from China are going to happen regardless of tariffs. In which case, the idea of disrupting the global supply chain to repatriate jobs back to the US is a non-starter. At least for China. I think it would work for other countries that are keeping the dollar strong by buying assets in the US (e.g. Japan, Ireland, UK, Germany, etc)

Maybe we get Chinese corporations to have more of a presence in the US and get them to repatriate their profits back to China, thus making the yuan stronger? It sounds insane, but what else would work change the equilibrium? Getting the US corporations in China to pull up stakes and leave? That seems like a non-starter. I have to admit to being dispirited after reading what Prof. Hudson had to share.

About the only upside to tariffs on Chinese goods is that it provides more tax income for the Fed Gov, per this article. Which if we were worried about funding of the US Fed Gov would be an issue.