Lambert here: Then there’s insurance. And re-insurance…

By Manthos Delis, Professor of Financial Economics and Banking, Montpellier Business School, Kathrin de Greiff, PhD candidate in Banking and Finance, University of Zurich and Swiss Finance Institute, and Steven Ongena, Professor in Banking, University of Zurich and the Swiss Finance Institute; Research Fellow, CEPR. Originally published at VoxEU.

The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement to limit the rise in global warming to 2°C compared to pre-industrial levels requires massive reductions in CO2 emissions in the next decades and near zero overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the next century onward. The limiting of total carbon emissions will leave the majority of fossil fuel reservesas ‘stranded assets’ (Carbon Tracker Initiative 2011, 2013, McGlade and Ekins 2015), with companies owing fossil fuel unable to use most of their reserves. The large fraction of potentially unburnable fossil fuels poses substantial financial risk to fossil fuel companies. Nevertheless, fossil fuel firms still largely invest in locating and developing new fossil fuel reserves (Carbon Tracker Initiative 2013). This ongoing investment, together with the already large fraction of potentially stranded assets, suggests that financial markets neglect the possibility that fossil fuel reserves become ‘stranded’ resulting in a ‘carbon bubble’, i.e. that fossil fuel firms are overvalued.

The potential effects of a carbon bubble on financial stability have been recently discussed in the academic literature (Weyzig et al. 2014, Schoenmaker et al. 2015, Batten et al. 2016) and are increasingly appearing on the agenda of regulators and supervisors (Bank of England 2015, Carney 2015, ESRB 2016). However, there is no clear evidence if whether, and to what extent, investors price the risk of unburnable carbon. Studying equity markets, recent research identifies an insignificant impact of climate/technology news on fossil fuel firms’ abnormal returns (Batten et al. 2016, Byrd and Cooperman 2016). This insignificant impact could be due to investors’ difficulties in assessing credible future climate policies and their impact on carbon-intense sectors, to investors believing in climate policy inaction, or to already accurately priced risk of climate-related stranded fossil fuels (Batten et al. 2016, Byrd and Cooperman 2016). Thus, we are missing insights into the effect of climate policy risk on the pricing of financial products.

Is There a Carbon Bubble in the Corporate Loan Market?

In a recent paper, we provide the first evidence for climate policy risk pricing, using evidence from the corporate loan market (Delis et al. 2018). Carbon-intensive sectors are largely debt financed, implying that the impact of stranded fossil fuels can easily spill over to the banking sector. This almost naturally generates the question of whether banks consider the risk that fossil fuel reserves will become stranded when originating or extending credit to fossil fuel firms. Essentially, this implies that if banks thoroughly consider the risk of climate policy exposure in the pricing of corporate loans, then no carbon bubble exists in the credit market.

Ideally, our main explanatory variable illustrating climate policy exposure would be the amount of stranded assets of a fossil fuel firm. However, such detailed estimates are not available. In principle, a devaluation of fossil fuel reserves can be caused by changes in regulation (policies), technologies, or carbon prices. Climate policies involve direct environmental regulations (e.g. pollution outputs and inputs) as well as stimulating the development of alternative technologies (for example, by subsidising instruments. The probability of stranded fossil fuel reserves is thus higher in countries with higher climate policy stringency. Therefore, we proxy the risk of stranded fossil fuel reserves by the risk of climate policy stringency, i.e. whether a country places considerable effort in climate change policies. A fossil fuel firm owing exploration rights for reserves in a country with strict climate policy faces a higher probability of reserves being stranded than a firm with fossil fuel reserves in a country with loose climate policy.

This implies that we require information on the total amount of fossil fuel reserves of firms across countries. As these data are not readily available in conventional databases, we hand-collect them from firms’ annual reports. Some firms hold fossil fuel reserves in more than one country, so we construct a relative measure of reserves for each firm, in each country, and in each year. Finally, we generate a firm-year measure of climate policy exposure (risk) from the product of relative reserves and either one of the Climate Change Cooperation Index (C3I) by Bernauer and Böhmelt (2013) or the Climate Change Policy Index (CCPI) by Germanwatch. These country-year indices, respectively available for the periods 1996-2014 and 2007-2017, reflect environmental policy stringency and thus risk.

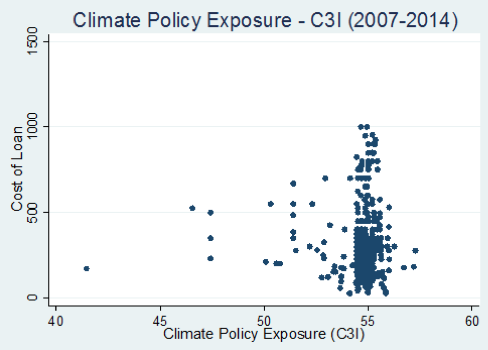

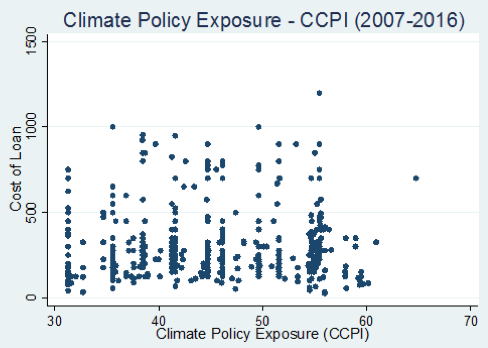

Figure 1 Climate policy exposure and the cost of loan

Note: The cost of loan in basis points is defined as the loan spread plus any facility fee.

Our baseline analysis compares the loan pricing of fossil fuel firms to non-fossil fuel firms and the loan pricing among fossil fuel firms based on their climate policy exposure. We strengthen the validity of this model via the fielding of many control variables and fixed effects (e.g. loan type and purpose, bank*year, and firms’ country fixed effects). As relevant environmental policy initiatives are recent, our analysis covers the period 2007-2016. We identify further differences in loan pricing by comparing, in the pre- and post-2015 periods, the terms of lending of fossil fuel to non-fossil fuel firms based on their climate policy exposure. The year 2015 signals a turning point because of the Paris Agreement and the intensified discussion of a carbon bubble.

Our Results: No Evidence of Pricing of Climate Policy Risk Prior to 2015, Some Pricing of Risk after 2015

Our results from the full 2007-2016 sample are consistent with a carbon bubble in the corporate loan market.

- We find no evidence that banks charge significantly higher loan spreads to fossil fuel firms.

- We find some evidence for higher loan fees to fossil fuel firms, but even these results are economically small and not robust across different specifications.

- However, when looking into the post-2015 period, we find the first evidence that banks increased their loan spreads to fossil fuel firms that are significantly exposed to climate policy risk. The economic significance is rather small: a one standard deviation increase in our measure of climate policy exposure implies that risky fossil fuel firms from 2015 onward are, on average, given a 2-basis points higher AISD compared to less-exposed fossil fuel firms, non-fossil fuel firms, and themselves before 2015.

To give an impression of the magnitude of this effect, the 2-basis point increase implies an increase in the total cost of the loan with a mean amount ($19 million) and maturity (four years) of around $200,000. Then, we hand collect data on the dollar value of fossil fuel reserves and find that the mean fossil fuel firm in our sample holds approximately $4,679 million in such reserves. Thus, it seems unlikely that the corresponding increase that we identify in the post-2015 period covers the potential losses from stranded assets.

We further investigate this finding by using the actual value of the holdings of proved fossil fuel reserves, instead of simply examining average differences between the fossil fuel and non-fossil fuel firms. Retaining the dichotomy between the pre-2015 and post-2015 periods, we find that a one standard deviation increase in our measure of climate policy exposure implies an AISD that is higher by approximately 16 basis points for the fossil firm with mean proved reserves scaled by total firm assets in the post-2015 period versus the non-fossil fuel firm. This implies an increase in the total cost of borrowing for the mean loan of $1.5 million. This extra cost of borrowing represents noticeable evidence that banks are aware of the climate policy issue and started pricing the relevant risk post-2015.

We also document a direct negative effect of climate policy exposure on the maturity of loans to fossil fuel firms in the post-2015 period.Moreover, we show a tendency of fossil fuel firms to obtain slightly larger loans compared to non-fossil fuel firms when environmental policy becomes more stringent. Even though the respective increase in loan amounts is economically rather small, our finding is in line with a substitution effect due to higher environmental policy risk from ‘lost’ access to equity finance toward bank credit. Finally, we document a slightly higher loan pricing to fossil fuel firms by ‘green banks’ (i.e. those participating in the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative) when climate policy risk increases.

Very interesting idea.

But shat is the term of the loans looked at?

“We strengthen the validity of this model via the fielding of many control variables and fixed effects”

“Many control variables” often serve to over fit a model.

> Our Results: No Evidence of Pricing of Climate Policy Risk Prior to 2015, Some Pricing of Risk after 2015

Huh. That’s a reason for optimism, I hope.

The day will inevitably come when the fossil companies will be shuttered. I would expect that what remains of our taxpayers will then be signed up to pay for the privilege.

I tried to go to the original paper via VoxEU, but it is paywalled at CEPR. 2 bps hardly strike me as a lot and perhaps not statistically significant. My most immediate questions are:

How big is the sample pre- and post-2015?

Are the companies with fossils exposure borrowing from the same banks at the same time or is there some bias here?

How predominant is lending to shale players which I would regard as riskier?

Having said that, it would be really interesting if it were true…

Try this link, it may be a slightly different version of the paper.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3125017

Perhaps an additional factor is that the banks may be pricing in that the extraction methods being financed may be riskier (deep water drilling, extreme cold in other areas) so even the non-shale firms borrowing the money are becoming riskier as the easier reserves have been tapped.

The paper does adjust for political instability factors.

After watching the US banks and the USA housing bubble in 2008, I don’t expect much leadership from banks as far as penalty rates for petrochemical producers.

The full paper has this statement: “We posit that this finding either suggests the existence of a carbon bubble due to the non-pricing of environmental policy exposure of fossil fuel firms or shows that banks specifically disregard the possibility that environmental policy will lead to considerable losses from stranded assets.”

BTW, why are these papers always double spaced after the abstract?

Is it because that is the format sent to reviewers?

It might save a few trees if the papers were single spaced for final issuance.

Thanks, will check out the paper.

Most US (and Canadian, maybe more?) academic papers must follow the Chicago Style Manual of Style (that’s paywalled but Wiki has some info here), which requires double spacing throughout, presumably so the profs have lots of room to write nasty things. See Modesto CA Junior College (no paywall).

In Mexico’s 2015 Gulf oilfield lease auctions, interest was low. People blamed the fact that oil was $40 per barrel.

In the Gulf oilfield lease auctions two months ago, interest was low even with oil at $70. Political analysts blamed the fact that Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a center leftist, most likely will be elected President. He has pledged to review these leases as well as current President Enrico Pena-Nieto’s neoliberal energy sector “reforms”.

I suspect the oil companies were looking beyond these more ephemeral issues.

https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/only-muted-interest-in-oil-and-gas-auction/

When I think about fossil fuels I think about piston aircraft & turbine jet fuels. Jet fuel is what the engines on airliners & freighters, & fighters were designed to burn. Even rocket fuels are now mostly kerosene which is essentially what jet fuel and diesel trucks use.

It is for the aviation industry and its applications that will be the last and longest place where fossil fuels will be used. It is because we do not have another fuel that provides the BTUs, the bang for the buck that gets these aircraft off the ground and keeps them in the air for limited and long periods of time.

For the investor then the calculations as to what aircraft demands will be over the next 200 years would direct what sort of fossil fuel banking supports one would most rationally make over the long term.

I’d say that fossil fuel companies with robust aviation departments will live the longest.

One can look at biofuels which do offer similar Btu types of fuels and DARPA has done R&D in this area with an eye to complete independence from oil in the ground. There is an issue with biofuels when they compete with growth of food.

The best future is the electric road powered by energy capture, meaning geothermal, solar, wind & wave. The ideal is to use batteries to get to the main thoroughfares and from there receive the electrical power necessary to power cars and trucks all across the nation.

R&D for the electric road is in its early stages. However it is definitely a possibility.

While we still will see diesel electric trains running on our rails for a long time, here also we will see a more complete conversion to electric rail systems.

I hope this consideration is of some use to somebody. Thanks

Thank you, Scott1. I (and not just me) have been arguing this for a *long* time, the trajectory is pretty clear, do you think decision-makers? But no! Anyway, thanks for the clear summation, I will use it wherever I can.

Life is going to slow down a good deal as reality sinks in. Aircraft will be lighter-than-air and travel much slower; ground vehicles will be mostly electric, ships will be at least partly wind-driven, and farm machinery will probably be mostly horse powered. I know that sounds like a fantasy, but the Amish (that have farms) do very well financially using horse power. Farms are essentially solar collectors, and horses are solar powered and solar produced.

But they probably won’t be used in cities because of the mess.

Ignoring the Technology Fairy, it certainly looks like aviation will the final refuge of hydrocarbon energy. There are no other solutions that work….yet.

The other major markets, cars and ships, are going to change radically over the next decade. The IMO 2020 decision is going to throw diesel and high sulfur fuel oil markets into turmoil. No one is ready because either they don’t think it will really happen or they figure there will be another, more radical, change soon after.

Diesel should explode in 2020 but then collapse again as first Europe and then other major consuming regions ban diesel engines. HSFO will be a huge problem. Where will it go? Ultimately ships will install scrubbers if the price of diesel explodes high enough over fuel. But then the IMO will start to ban CO2 and not just sulphur; that is why shipowners are unconvinced about 2020.

We need to stop burning oil. Diesel is a horrid fuel so that will go first. Then gasoline.

Good luck trying to make enough green power to run everything!

“Diesel will go first”?

Correct me if I’m wrong (no chemical engineer here) but when you refine crude oil to gas, diesel and kerosene, you always get all three. You can decide a bit which one to emphasize at cost to the others, you can use different crude oil types to get different end results, but more or less you always get all three.

Then, what do you expect to use for trucks, trains and ships if not diesel? Or heating: ~25% here in europe use oil aka diesel, 48% use natural gas. With gasoline aka cars running on gas or diesel, we are basically at a point where we can do without. It will cost a lot in infrastructure, but it’s doable. With diesel not really, and with kerosene “hell no” basically as others pointed out.

A sophisticated refinery can choose between diesel or gasoline. I suppose they could also crack the kero into gasoline if they wanted. So the short answer is that a modern, complex refinery does not have to make all three.

When I said that diesel will go first, I meant for cars…and then trucks.

The home heating market is still a big one for diesel but that will go as well with mainly Germany switching to nat gas or electricity.

Trains might remain diesel but trucks will have to change as well. Road diesel is going to disappear in Europe, and good riddance.

Jet fuel remains a problem until the technology fairy comes back.

What’s to stop an energy extractor from shipping their fossil fuel to another country with higher emission goals?

A new report details how California’s bold plans to reduce oil consumption and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement could be canceled out by the state’s own oil production.

Well, regulation, of course. Oh wait…

This already takes place in practice. Norway is 100% green power (mostly hydro) but exports a massive quantity of gas and oil. The first world “dumps” its low quality diesel and gasoline into Africa and parts of the Middle East. China still burns fuel oil for power. Saudi still burns millions of barrels a day of crude for power, but imports heavy fuel oil and will increase those imports as it increases its refining capacity. Etc.