Yves here. The idea that the effect of tax evasion means that the rich are even richer than they appear ought to be obvious, yet the notion is almost entirely absent from discussions of income and wealth inequality. Not surprisingly, in classic drunk under the streetlight behavior, some analysts do adjust income inequality data for the effect of transfers, which lowers the apparent level of inequality, without trying to adjust for what is almost certainly the much larger impact of tax evasion. Gabriel Zucman, one of the co-authors of this post, has estimated in his important bookk The Hidden Wealth of Nations that 8% of global household wealth is in tax havens, which gives a feel for the magnitude of tax evasion.

By Annette Alstadsæter, Professor, School of Economics and Business, Norwegian University of Life Science, Niels Johannesen, Professor of Economics, University of Copenhagen, and Gabriel Zucman. Assistant professor, UC Berkeley. Originally published at VoxEU

Who evades taxes in developed economies? The question is fascinating in its own right and matters a great deal for the study of inequality because scholars typically rely on tax records to estimate the concentration of income and wealth (e.g. Piketty et al. 2018). If the rich dodge taxes more than the poor, tax records will underestimate inequality.

In recent research (Alstadsæter et al. 2017), we set out to estimate how tax evasion varies with wealth and to correct inequality statistics for differences in evasion rates. We conduct a detailed investigation of the case of Scandinavian countries, where particularly good data exist. We start our examination with audits conducted randomly by tax authorities. These audits are the current ‘gold standard’ in the literature to measure tax evasion (e.g. Kleven et al. 2011), but they have a key limitation: they do not satisfactorily capture tax evasion by the very wealthy, because they fail to detect sophisticated forms of evasion involving anonymous shell companies and secret offshore accounts.

Exploiting Leaked Data to Shed Light on tax evasion in Scandinavia

To bridge this gap, we use new data leaked from offshore financial institutions and information from recent tax amnesties. These new data sources enable us to capture the forms of tax evasion conducted by households with dozens of millions of dollars in wealth. They allow us to shed a bright light on a world that is not typically observable to researchers. By combining leaked data, amnesty data, and random audit data, we can thus provide a much more comprehensive picture of how much each social group evades in taxes than was available until now.

The first leaked dataset we use is a trove of data leaked from HSBC Switzerland, later known as the ‘Swiss leaks’. In 2007, an employee extracted the internal records of the bank and turned the data over to the French government. The leaked documents included the complete internal records of the more than 30,000 clients of the bank. At the time, HSBC Switzerland was a major actor in offshore banking, managing assets of about $120 billion, or approximately 5% of all the foreign wealth managed by Swiss banks.

This HSBC leak is a unique source of information to study tax evasion because the leak is a random event and because it comes from a large and arguably representative offshore bank. Who owned the wealth hidden in that Swiss bank at the time of the leak?

We find that the wealthier you were, the more likely you were to hide assets at HSBC Switzerland. Moreover, for those who concealed assets in HSBC Switzerland, tax evaders hid on average the equivalent of 40% of their true wealth (with no trend across the wealth distribution). As a result, although HSBC Switzerland had dozens of thousands of clients at the time of the leak, the wealth held there was concentrated in just a few hands.

In a second step, we conduct a similar analysis in other samples of individuals with offshore wealth, namely owners of shell corporations exposed in the Panama Papers, and taxpayers who voluntarily disclosed previously hidden offshore assets by using tax amnesties. We find similar patterns in all these samples. In all cases, offshore wealth appears to be extremely concentrated at the top of the wealth distribution: by our estimates, 50% of offshore assets belong to the wealthiest 0.01% households, and around 80% belong to the wealthiest 0.1%.

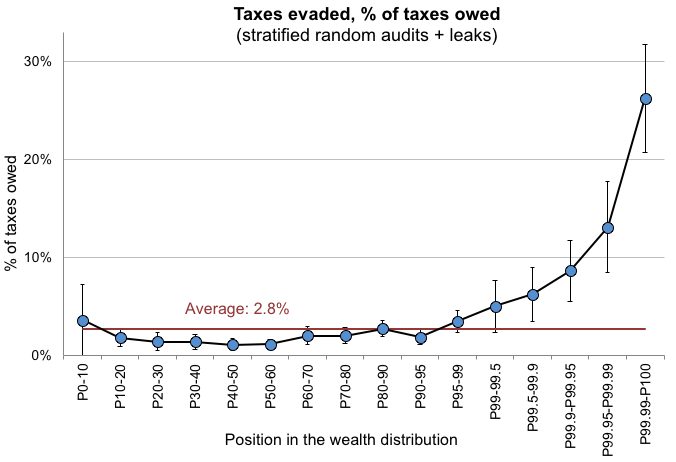

The Richest Households Evade About 25% of Taxes Owed by Concealing Assets and Investment Income Abroad

When we apply this distribution to available estimates of the macroeconomic amount of wealth hidden in tax havens (Zucman 2013, Alstadsæter et al. 2018), we find that the top 0.01% richest households evade about 25% of the taxes they owe by concealing assets and investment income abroad. Throughout our research, we maintain a clear distinction between legal tax avoidance and illegal evasion. Thus, this estimate only takes into account the wealth held offshore that evades taxes; it excludes properly declared offshore assets. When we add the tax evasion detected in random audits, total evasion in the top 0.01% reaches 25-30%, versus 3% on average in the population (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The ratio of taxes evaded to taxes owed, by wealth group

Do our findings apply to other countries? We certainly do not claim that the pattern of evasion by wealth group that we found in Scandinavia holds everywhere as a universal law. If anything, tax evasion among the rich might actually be even higher in other developed economies, given that Scandinavian economies rank among the countries with the strongest respect for the rule of law, highest tax morale, and lowestamount of wealth held in tax havens (Alstadsæter et al. 2018). Down the wealth ladder, other developed economies are likely to have low levels of evasion (like Norway, Sweden, and Denmark), because most economic activity takes place in the corporate and public sectors, where third-party reporting strongly limits tax evasion.

Why Do the Rich Evade Taxes? Because They Can

Why do the rich evade so much? Because for them tax evasion is possible: there is an industry – in Switzerland, Panama, and other tax havens around the globe – that provides wealth concealment services to the world’s wealthiest individuals. This industry typically only targets the very wealthy (people with more than $20 million or sometimes $50 million to invest), as serving too many would-be evaders would increase the risk for these banks and law firms that they would be discovered violating the law. Moderately wealthy individuals (below the top 0.1%) do not have access to these services and therefore do not evade as much tax. Further down the ladder, the majority of the population only earns wages and pension income, which cannot be hidden from the tax authority.

Because it is unevenly distributed across wealth groups, tax evasion has important implications for measured wealth inequality. In Norway, for instance, the wealth share of the top 0.01% increases by around 25% when accounting for hidden offshore assets.

Our final results relate to policy discussions on the ongoing fight against offshore tax evasion. We show that disclosures of offshore wealth under the tax amnesties were associated with sharp increases in reported wealth, capital income, and tax liabilities, but no increase in outcomes associated with legal tax avoidance. These results imply that the potential revenue gains from policies that effectively deter offshore tax evasion are considerable. Past crackdowns on offshore tax evasion mostly induced tax evaders to shift assets to safer havens (Johannesen and Zucman 2014) rather than to disclose more assets at home (Johannesen et al. 2018). However, it remains to be seen whether the most recent enforcement mechanism, automatic information exchange, can significantly reduce the supply of wealth concealment services.

To reduce top-end evasion significantly, it is key to shrink the supply of wealth concealment services. This can be done by changing the incentives faced by the law and financial firms in tax havens, for instance by applying trade tariffs to non-cooperative tax havens and steep financial sanctions to the firms found abetting tax dodging (Zucman 2015).

See original post for references

Thank you for this – it agrees with my own observations, that tax evasion, in Europe in particular, is rampant among the super-rich.

Two observations to add: first, that offshore tax havens are overflowing with money from nowhere that belongs to no one. The list of shareholders in private funds is routinely filled with shell companies with nondescript names – and in many cases, with listed addresses in European “banking centers” (read: tax havens), e.g., Luxembourg, Isle of Man, Guernsey, Malta, etc.

Second: no one in Europe seems to own anything, at least compared to the U.S. The average person on the street may own a flat (though more likely not) and have some minimal savings, but not much in retirement savings, since they are more likely to rely on a pension. And European pension plans – government or corporate – have some assets, but are more likely to be pay-as-you-go.

So who owns everything in Europe?

Look up European companies individually, and some are publicly traded (but who owns the stock?), but many are simply listed as “private”. And when you dig even further, those “privately held” companies are routinely held in a maze of shell companies that own each other, the net result being that real control is obscured and taxes don’t get paid. The most glaring example is IKEA, which is “owned” by a complex network of “non-profit” shell companies, with a minimum of taxes getting paid – even though the family still seems to have complete control over the operation.

And remember that statistics like the Gini coefficient get calculated from tax revenues. But if tax revenues for the 0.01% are a work of legal fiction, how accurate is the final statistic? And likewise with measures of the distribution of wealth – if some of the largest companies in Europe are “owned” by “non-profits” or offshore shell companies, and not by the families that really control them, how accurate are the statistics showing a supposedly egalitarian society?

Thank you and well said.

Further to your reference to shells and their jurisdictions, they are often used to conceal (beneficial) ownership of British real estate and football clubs.

It’s amazing that the biggest landowner in the United Kingdom and a bastard descendant of Charles II, the Duke of Buccleuch, appears to benefit from the use and fruits of 460k acres, but not own any of it.

The in laws of David Cameron own estates in Oxfordshire (Ginge) and on Jura through similar networks.

Ken Bates acquired Chelsea Football Club through networks in Mauritius.

Thank you, Yves.

Just a few things to add:

Herve Falciani, the former HSBC employee responsible for the leaks, was arrested in Barcelona, where he has lived since 2013, a month ago and is waiting to be extradited to Switzerland, a quid pro quo for Catalan nationalists being held in Switzerland.

One of the killers of Stephen Lawrence was similarly arrested in Barcelona, where he has lived for two years, last week-end. There are Catalan nationalists seeking refuge in Scotland.

Many years ago, when working in Brussels, it was interesting to hear German and EU officials wonder, perhaps knowingly, why the UK was not interested in receiving information obtained by German authorities on tax evasion by UK citizens.

Having worked at Coutts and, at times, the wealth arms of HSBC, BNY Mellon and Barclays, I reckon the above figures are underestimates.

Thank you for this post. Funny that the Panama Papers have fallen off the corporate media radar screen. In addition to the proposed solution by the authors in the last two paragraphs of this article, I would support legislation that funds increased IRS monitoring of both shell companies and funds transfers to and from tax havens, intensive tax audits of the top 0.01% due to the pervasive pattern of illegal tax evasion by members of that segment, and imposes financial penalties and incarceration or deportation of those persons who engage in this illegal behavior in order to deter it. Sanctions should also apply to corporations that locate their offices in offshore tax havens to avoid taxation of their U.S. income through transfer pricing with shell subsidiaries, etc.

The U.S. is among the most benign tax jurisdictions in the world. There is little reason why a narrow segment of the population should continue to be allowed to engage in illegal tax evasion.

I’m not sure I would characterize the U.S. as a ‘benign’ tax jurisdiction. A person contemplating starting a business needs to ramp up revenues pretty quickly to have much left after FICA and regressive state taxes. I reviewed someone’s taxes who grossed $25,000, had taxable income of $13,000, but paid about $6,000 in FICA, state, and federal income taxes. (I say ‘reviewed’: the CPA had already prepared the taxes). The US tax code is set up such that, in order to pay at low rates, one must contribute to a retirement plan. Many small business people don’t think abstractly enough about money to be able to do that. They’re afraid of stocks, perhaps with good reason given the downturns of the last twenty years.

Fifty years from now, I suspect economists may think that the grand deal to save social security in the ’80s was bad for economic growth. The payroll tax was much, much lower in the 1950s when Americans were starting small businesses in droves. Our workforce participation problem now is almost totally due to the fact that people aren’t starting small businesses the way they did before 2000.

The answer is that it is because they can.

The rich have this mentality that taxes are for us lowly peasants, while they should be entitled to not pay any taxes. You can see this most visibly in the Koch brothers, but there are other examples.

The Panama Papers were very revealing in that regard and I think that the reason why the corporations controlling the mainstream media don’t want to draw more attention is because the rich own the media. It would be friendly fire, so to speak.

In reality, the tax system already favors the rich. Take for example the American tax system. To give an example, capital gains are taxed at a lower rate than wages, especially when you get to the upper middle class brackets. Other things like mortgage interest deductions favor those with lots of property.

The brutal reality is that the system is controlled by the rich for the purpose of making the rich even wealthier at our expense.

I think that the punishment for high net worth individuals engaging in tax evasion should be very harsh indeed. Of course that would mean transforming the current system, a plutocracy pretending to be a democratic society into a society that is genuinely interested in making the common citizen better off.

This is a crucial thing rarely mentioned. From time to time EU authorities say something bold about tax evasion and it is dutifully noticed by the press but is rapidly forgotten by both. A bit of good news is that apple will finally have to pay the 13 billion euro penalty fee in Ireland that was imposed two years ago. This is another point. Once fiscal authorities detect tax evasion schemes, try to end those and impose fees, how many times the rich use regulatory loopholes and lobby to avoid fees or directly obtain fiscal amnesty from friendly governments?

At first I thought the blog was about legal tax evasion/avoidance, but wow 25% of taxes of the top .1% is illegal tax evasion?

Something that didn’t appear to be clarified is if the tax evasion is on total wealth or annual “income” of any kind. And how is that be affected by compound interest on the shielded wealth. Or is that all baked into the headline numbers in the graph?

Just so you know, “tax evasion” = illegal. “Tax avoidance” = legal.

One comment about tax avoidance at the bottom end. From what I have seen, a lot of “independent contractors” making not a lot of money don’t declare a bunch of it. Even though they don’t pay much “income tax”, they are subject to the 15% “self-employment tax” which is FICA. One of the reasons that they are independent contractors is because the employer doesn’t want to deal with that paperwork, or pay the employer’s half (e.g. the nanny tax).

So the tax avoidance at the low end actually has a real negative economic impact on these workers in their later life because it reduces their social security base wages and therefore reduces their social security checks in retirement. It can also delay their ability to receive social security disability as you need to demonstrate 40 quarters of paying into the system to be eligible. This is a big difference from the wealthy who don’t see that they suffer any negative future income impacts due to their tax evasion, unless they get caught.

I know a number of different kind of contractors/mechanics who will cut you a good percentage deal if you tell them you will pay in cash. I am pretty sure that the underground economy is fairly large and mostly all based upon cash transactions.

Thus the desire of the govt/banking/credit card industries to do away with cash.

that’s a good point about their motivation, probably other motives, too, but that certainly sounds right.

Of course the rich (in that time the clergy and nobility) paid not taxes in France before the revolution. I suspect that at least the clergy paid no taxes in any country, and the nobility low to no taxes after the personal service as a Knight went away. It was only the French Revolution that to start with confiscated the church lands and then removed all privilege that the elite paid taxes in France or possibly got their head chopped off. Recall the difficulties of the income tax in the UK in the 19th century. As a result of inheritance and other taxes a lot of estates got sold off.

When the UK tried recently to require the offshore places to have open registers of who owns companies, the offshore domains cried bloody murder (in particular the BVI) as this is a large part of how they get their money and jobs.