By Raj Chetty, Professor of Economics, Harvard University, Nathaniel Hendren, Assistant Professor of Economics, Harvard University, Maggie R. Jones, Senior Economist and Income Research Lead, U.S. Census Bureau , and Sonya R. Porter, ssistant Center Chief of Research, Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications, U.S. Census Bureau. Originally published at VoxEU.

Racial disparities in income and other outcomes are among the most visible and persistent features of American society. The sources of these disparities have been studied and debated for decades, with explanations ranging from residential segregation and discrimination to differences in family structure and genetics.

Most previous work on racial disparities has studied inequality within a single generation of people. In a new study, we analyse how racial gaps change across generations. Using de-identified data covering 20 million children and their parents, we show how race currently shapes opportunity in the US and how we can reduce racial disparities going forward.2

Finding #1: Hispanic Americans are moving up in the income distribution across generations, while Black Americans and American Indians are not.

We study five racial and ethnic groups: people of Hispanic ethnicity and non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Asians, and American Indians. By analysing rates of upward and downward mobility across generations for these groups, we quantify how their incomes change and predict their future earnings trajectories.

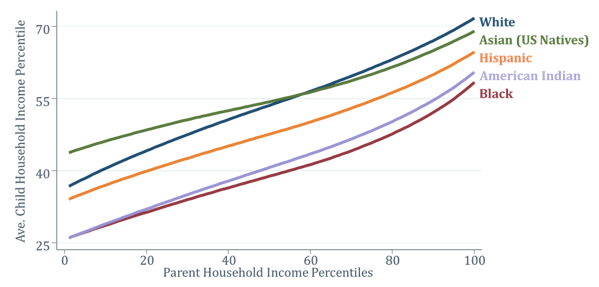

Figure 1 Children’s incomes vs. parents’ incomes, by race and ethnicity

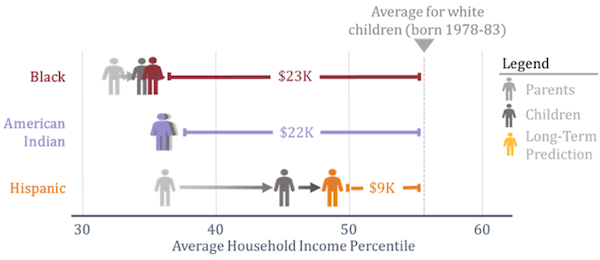

Hispanic Americans have rates of upward income mobility across generations that are slightly below those of whites. Hispanics are therefore on a path to moving up substantially in the income distribution across generations, potentially closing much of the present gap between their incomes’ and those of white Americans.

Asian immigrants have much higher levels of upward mobility than all other groups, but Asian children whose parents were born in the US have levels of intergenerational mobility similar to white children. This makes it more difficult to predict the trajectory of Asian Americans’ incomes, but Asians appear likely to remain at income levels comparable to or above white Americans in the long run.

In contrast, black and American Indian children have substantially lower rates of upward mobility than the other racial groups. For example, black children born to parents in the bottom household income quintile have a 2.5% chance of rising to the top quintile of household income, compared with 10.6% for whites.

Growing up in a high-income family provides no insulation from these disparities.American Indian and black children have much higher rates of downward mobility than other groups. Black children born to parents in the top income quintile are almost as likely to fall to the bottom quintile as they are to remain in the top quintile. By contrast, white children born in the top quintile are nearly five times as likely to stay there as they are to fall to the bottom.

Because of these differences in economic mobility, blacks and American Indians are ‘stuck in place’ across generations. Their positions in the income distribution are unlikely to change over time without efforts to increase their rates of upward mobility.

Figure 2 Changes in income across generations, by racial group

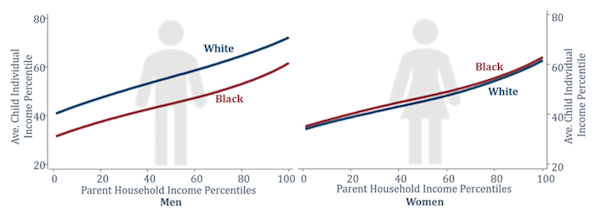

Finding #2: The black–white income gap is entirely driven by differences in men’s, not women’s, outcomes.

Among those who grow up in families with comparable incomes, black men grow up to earn substantially less than the white men. In contrast, black women earn slightly more than white women conditional on parent income. Moreover, there is little or no gap in wage rates or hours of work between black and white women.

We find analogous gender differences in other outcomes: black-white gaps in high-school completion rates, college attendance rates, and incarceration are all substantially larger for men than for women. Black women have higher college attendance rates than white men, conditional on parental income. For men, the gap in incarceration is particularly stark: 21% of black men born to the lowest-income families are incarcerated on a given day, far higher than for any other subgroup.

Figure 3 Children’s incomes versus parents’ incomes, for black and white men and women

Finding #3: Differences in family characteristics – parental marriage rates, education, wealth – and differences in ability explain very little of the black–white gap.

Black children are much more likely to grow up in single parent households with less wealth and parents with lower levels of education – all factors that have received attention as potential explanations for black-white disparities. But, when we compare the outcomes of black and white men who grow up in two-parent families with similar levels of income, wealth, and education, we continue to find that the black men still have substantially lower incomes in adulthood. Hence, differences in these family characteristics play a limited role in explaining the gap.

Perhaps most controversially, some have proposed that racial disparities might be due to differences in innate ability. This hypothesis does not explain why there are black–white intergenerational gaps for men but not women. Moreover, black-white gaps in test scores – which have been the basis for most prior arguments for ability differences – are substantial for both men and women. The fact that black women have outcomes comparable to white women conditional on parental income despite having much lower test scores suggests that standardised tests do not provide accurate measures of differences in ability (insofar as it is relevant for earnings) by race, perhaps because of stereotype anxiety or racial biases in tests.

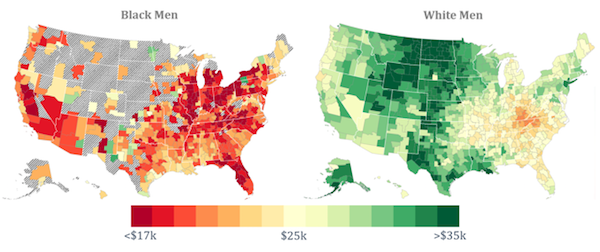

Finding #4: In 99% of neighbourhoods in the United States, black boys earn less in adulthood than white boys who grow up in families with comparable income.

One of the most prominent theories for why black and white children have different outcomes is that black children grow up in different neighbourhoods than whites. But, we find large gaps even between black and white men who grow up in families with comparable income in the same Census tract (small geographic areas that contain about 4,250 people on average). Indeed, the disparities persist even among children who grow up on the same block. These results reveal that differences in neighbourhood-level resources, such as the quality of schools, cannot explain the intergenerational gaps between black and white boys by themselves.

Black–white disparities exist in virtually all regions and neighbourhoods. Some of the best metro areas for economic mobility for low-income black boys are comparable to the worst metro areas for low-income white boys, as shown in the maps below. And black boys have lower rates of upward mobility than white boys in 99% of Census tracts in the country.

Figure 4 Average incomes for black and white men who grow up in low-income (25thpercentile) families

Finding #5: Both black and white boys have better outcomes in low-poverty areas, but black-white gaps are bigger in such neighbourhoods.

Despite the prevalence of black–white gaps, there is substantial variation in rates of upward mobility for both black and white boys across areas, as illustrated in the maps above. Areas that have higher rates of upward mobility for whites tend to have higher rates of upward mobility for blacks as well. For both blacks and whites, upward mobility is highest for children who grow up in the Great Plains and the coasts and lowest in the cities in the industrial Midwest. One notable exception to this pattern is the Southeast, where whites have especially low rates of upward mobility (relative to other whites nationwide) but blacks do not.

Both black and white boys have better outcomes in neighbourhoods commonly perceived to be ‘good’ areas: Census tracts with low poverty rates, high test scores, and a large fraction of college graduates. However, black–white gaps are larger on average for boys who grow up in such tracts, because whites benefit more from living in such areas than blacks do.

Finding #6: Within low-poverty areas, black–white gaps are smallest in places with low levels of racial bias among whites and high rates of father presence among blacks.

In low-poverty neighbourhoods, two types of factors are most strongly associated with better outcomes for black men and smaller black-white gaps: low levels of racial bias among whites and high rates of father presence among blacks.

Black men who grow up in tracts with less racial bias among whites – measured by testing for implicit bias or explicit racial animus in Google searches – earn more and are less likely to be incarcerated.

Higher rates of father presence among low-income black households are associated with better outcomes for black boys, but are uncorrelated with the outcomes of black girls and white boys. Black father presence at the neighbourhood level predicts black boys’ outcomes irrespective of whether their own father is present or not, suggesting that what matters is not parental marital status itself, but rather community-level factors associated with the presence of fathers, such as role-model effects or changes in social norms.

Finding #7: The black–white gap is not immutable: black boys who move to better neighbourhoods as children have significantly better outcomes.

Black men who move to better areas – such as those with low poverty rates, low racial bias, and higher father presence – earlier in their childhood have higher incomes and lower rates of incarceration as adults. These findings show that environmental conditions during childhood have causal effects on racial disparities, demonstrating that the black-white income gap is not immutable.

The challenge is that very few black children currently grow up in environments that foster upward mobility. Fewer than 5% of black children currently grow up in areas with a poverty rate below 10% and more than half of black fathers present. In contrast, 63% of white children grow up in areas with analogous conditions.

Implications

Differences in rates of mobility out of and into poverty are a central driver of racial disparities in the US today. Reducing the black–white gap will require efforts that increase upward mobility for black Americans, especially black men.

Our results show that the black–white gap in upward mobility is driven primarily by environmental factors that can be changed. But, the findings also highlight the challenges one faces in addressing these environmental disparities. Black and white boys have very different outcomes even if they grow up in two-parent families with comparable incomes, education, and wealth, live on the same city block, and attend the same school. This finding suggests that many widely discussed proposals may be insufficient to narrow the black–white gap themselves, and suggest potentially new directions to consider.

For instance, policies focused on improving the economic outcomes of a single generation – such as temporary cash transfers, minimum wage increases, or universal basic income programs – can help narrow racial gaps at a given point in time. However, they are less likely to narrow racial disparities in the long run, unless they also change rates of upward mobility across generations. Policies that reduce residential segregation or enable black and white children to attend the same schools without achieving racial integration within neighbourhoods and schools would also likely leave much of the gap in place.

Initiatives whose impacts cross neighbourhood and class lines and increase upward mobility specifically for black men hold the greatest promise of narrowing the black-white gap.There are many promising examples of such efforts: mentoring programmes for black boys, efforts to reduce racial bias among whites, interventions to reduce discrimination in criminal justice, and efforts to facilitate greater interaction across racial groups. We view the development and evaluation of such efforts as a valuable path forward to reducing racial gaps in upward mobility.

Authors’ note: This column and all figures that appear in it are based on the paper “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective” by Raj Chetty (Stanford), Nathaniel Hendren (Harvard), Maggie R. Jones (U.S. Census Bureau), and Sonya Porter (U.S. Census Bureau). The views expressed in this executive summary are not necessarily those of the U.S. Census Bureau. The statistical summaries reported in these slides have been cleared by the Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board release authorisation number CBDRB-FY18-195

Notes and references can be found at the original post.

A counterpoint–Wealth by religion in the U.S.

Hindus are the richest, followed by Jews etc.

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/11/how-income-varies-among-u-s-religious-groups/

this was done apparently by grouping together all those with spanish surnames as hispanic. analogous to grouping all english speaking americans together without regard to race. the largest part of the spanish surname demographic are Mexicans whose racial demographic is 80% indigenous. NC has a mainly white readership, nothing wrong with that but things like this slip in here all the time. Accuracy in articles concerning race matters, at least to those of us affected by it. this is not a complaint rather an observation.

What you say is not true. If you read the original article, the researchers get self-reported race and ethnic origin from survey data and censuses.

I admit that my eyes glaze over when confronted with endless graphs, charts and statistics. The problem isn’t that we don’t know what ails us…thousands of studies and research projects focusing on poverty and race relations in America are commissioned every year, but none of them reveal anything profoundly new. They confirm in one way or another what we already know to be true. The problem is that neoliberal ideology and its emphasis on “market based solutions” is no solution at all. In fact it is precisely because we are so beholden to the illusion of a divine and perfect market that communities crumble and the people who live in them fester in despair and misery while we wait for an ideologically correct solution that will never come.

The huge problems we face, from decaying public infrastructure, endemic poverty and systemic discrimination to the broken healthcare system and the looming climate crisis, can never be solved from within a system that is fundamentally opposed to the idea of using public money to fund and maintain structures and institutions that benefit all citizens and help the most vulnerable live dignified lives as full members of their communities. If even the threat of apocalyptic annihilation changes nothing…what hope to we have? Does anybody really think Bernie, Liz or whoever is going to rise to power after the Trump fiasco has run its course and usher in a new New Deal?

My not-so-bold prediction: nothing substantial will change until a massive family blogging crisis hits us between the eyes. Then things will change. But likely not for the better.

“Our results show that the black–white gap in upward mobility is driven primarily by environmental factors”

LOL. Really?

This line makes it seem like blacks would do just fine if they lived in nicer neighborhoods and worked hard, maybe cleaned up their yards and smiled more.

Blacks in America have been free, more or less, for perhaps two generations. They are still clustered in ghettos in the North. In the South, the century and a half of post-slavery policies have gutted black communities and destroyed most hope of education.

So, yes, it’s environmental factors. But the factors were put in place and are maintained by whites.

One way to deal with racial differences in economic mobility might be to increase the downward mobility for all, with differentials added to even things out at the bottom.

The dismissal of the neighborhood effect (access to community resources like good schools matters most) is belied by the later statement that black and white boys both do better in good neighborhoods, although white boys do much better; while only 5% of black boys live in such neighborhoods compared to 63% of whites.

Obviously, neighborhoods matter a lot.

Finding #4, was a bit of a revelation, for I thought that equalizing access for blacks to good schools in neighborhoods w/ a large white population would go very far toward closing the income gap, however, did not, but rather the lessening of race bias and the considerable father presence did accomplish such. I haven’t dug deep into this study (and I will try to), but I’m wondering if the low poverty areas in the study included neighborhoods that were all or mostly black or were the neighborhoods all predominantly white?

Of course race is but one category, with the overarching one being economic/financial, since multigenerational wealth ensures economic privilege across many generations . . . . hence, Old Money!