By Enrico Verga, a writer, consultant, and entrepreneur based in Milan. As a consultant, he concentrates on firms interested in opportunities in international and digital markets. His articles have appeared in Il Sole 24 Ore, Capo Horn, Longitude, Il Fatto Quotidiano, and many other publications. You can follow him on Twitter @enricoverga.

As we speak, the media is debating the crisis in Turkey, generally providing one-sided interpretations of it as due to the sovereignism (nationalism) of Erdogan.

Let’s look at this crisis in detail. It is a story of cultural and economic expansion aimed at acquiring renewed geopolitical weight, an assertive foreign policy offset by a lack of domestic energy resources and a bubble of easy credit financed by foreign (as well as domestic investment). In recent years, a bit of healthy national hubris has played a role as well.

Efforts at Cultural and Economic Expansion

The roots of the Turkish crisis are deep and in my judgment reach back to 1990. After being rejected for membership in the EU, Turkey, then under Ozal’s leadership, tried to create its own place within the new global order. Pressures in this direction were only accelerated by the fall of the Berlin wall and the end of Cold War-style bipolarism. Erdogan is less the inventor than the continuer of a pan-Turkic, sovereignist vision that became strong already in that earlier era.

The many individual pan-Turkic initiatives can be seen in light of a broad ambition to integrate all of the Turkish-speaking republics (in central Asia) under Turkish leadership. A principal instrument of this foreign policy strategy is TIKA (the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency), which operates through a mix of humanitarian aid, infrastructure investments, and support of Turkish businesses that export to “new” central Asian markets.

An internal economic crisis led however to a temporary cool-off of these ambitions. Also motivating this retrenchment was the realization by democratic Turkey that many of the ex-Soviet republics it had been supporting were in fact a bit resistant to a similar concept of democracy. Since then, Turkey has experienced strong economic growth, albeit with several gaping points of weakness, which though papered over by foreign investment have never truly healed.

We then come to the Erdogan period.

An Assertive Foreign Policy

Turkey needs room to grow – not in the sense of physical territory, but in the sense of outlets for exports and, also, places where it can exercise its financial influence. On the central Asian front, it has created devices for building links (such as the CCTS, the Cooperation Council of Turkish-Speaking States), which have, with ups and downs, tried out various approaches.

One aspect of the problem is that Turkey is a nation that exists within a sort of bipolarism. On the one hand, a large part of the country is tightly interwoven with the Middle East (which doesn’t mean that calling a Turk an Arab is a good idea if you want to live out the day). On the other, there is Istanbul, the vanguard of moderate Turkey: one could call it the Western face of the Islamic nation, remembering that it was for centuries Constantinopolis, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Turkish power projection politics has to deal with four fronts: the Western bloc, the Mideast (including the Kurds, a sort of “passion” of the Turkish government), Central Asia, and the Caucasus group. In each of these areas there are regional actors (Iran, Israel, Armenia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria) as well as the big kids on the block (USA, Russia, and, less overtly, Europe and China). Turkish politics has been fairly erratic, involving continual moves to favor its regional interests while trying not to irritate the big kids, on whom it depends for financial support through private investment and energy supplies. The result is a gigantic mess.

On the Mideast front, for example, the participation of Turkey in the Syrian conflict and the war against ISIS has often been rather ambidextrous. When Turkey entered the war against ISIS (whom many have suggested receives support from Turkish sources), the first to suffer the consequences were not ISIS terrorists but the Peshmerga Kurds (allies of the US against ISIS), who were promptly bombarded by the Turkish army. On the Syrian front, Turkey’s actions have been similarly ambivalent, first pushing for the fall of Assad (who was in turn supported by Iran and Russia), but then becoming a lukewarm supporter of the Syrian strongman. All of this can however be explained without much difficulty.

A Shortage of Domestic Energy Resources

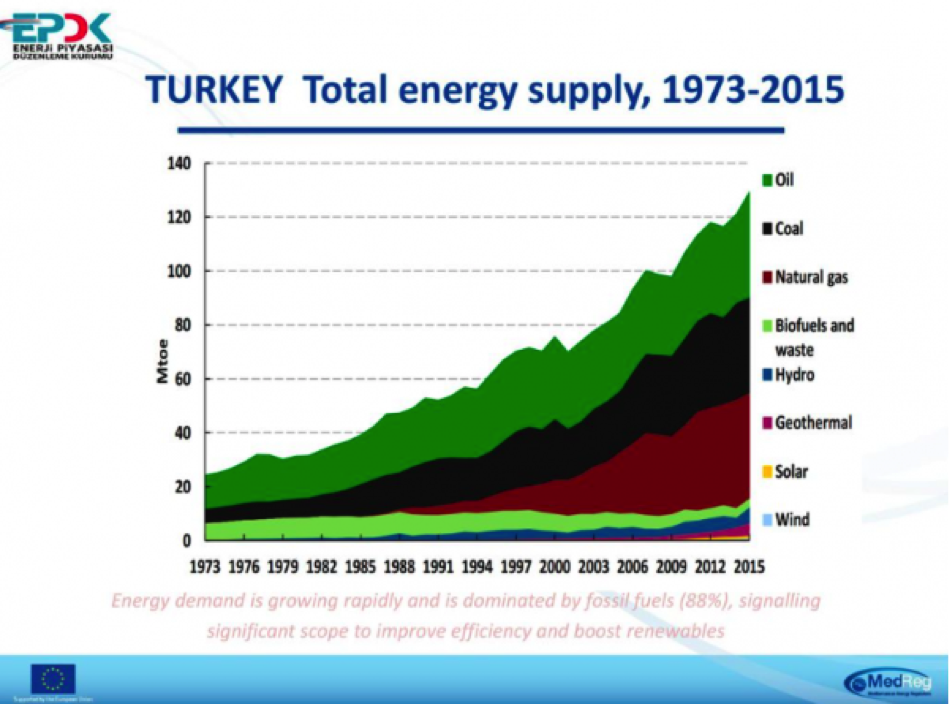

In fact, in order to power its industries, Turkey needs a quantity of energy that it cannot provide by itself. As this graph by the Turkish statistics office shows, its energy domand has grown very quickly.

This motive underpins a series of alliances, such as one assuring a chunk of the energy coming through the Baku (Azerbaijan)/Tbilisi (Georgia)/Ceyhan (Turkey) pipeline, or BTC for short, along the route of the Caucasus.

The struggle for oil pipelines is in turn wound up with that for natural gas. According to an analysis by Oxford University (data from 2016), Russia and Iran are Turkey’s major gas suppliers. However, Iran has reduced its gas exports to Turkey. Turkey has therefore had to fall back on Russia. It is maybe not an accident that after Trump’s declarations (which were not connected to gas sales), Erdogan immediately phoned Putin.

Putin is in any case a curious ally. Earlier, during the Syrian conflict, he and Turkey were on opposite sides, with Turkey part of the alliance between the USA, EU, and various and sundry rebels hoping to depose Assad. RT went as far as to assert that Turkey was consorting economically in broad daylight with ISIS, and Israel seconded the accusation. After a series of Russian strategic bombardments cutting the supply lines of traffickers smuggling oil into Turkey (operations of which the Turkish government claimed ignorance), Erdogan decided it was sensible to make overtures to Putin. Did all of this activity benefit the Turkish people? Not much. In fact, the continual vacillations of Turkish foreign policy have created considerable confusion among historical (Western) allies while irritating potential regional allies (Iran, Iraq) and the big Russian brother.

A Bubble of Easy Credit Fueled by Foreign Investment

Beside the international situation, there is also a (degenerating) financial situation. Turkey has grown quickly in recent years, but in a way that has been tilted toward financial markets and easy speculation (for example retail and homebuilding) at the expense of production and infrastructure investment.

The natural question is, “Who is financing these inflows?” Europe, or more accurately European banks, has decided that it is in its (its banks’) interest to make short-term loans and real-estate mortgages in Turkey rather than in its domestic markets (particularly cash-strapped Italy, Spain, and France) The three banks most deeply implicated are located in three nations each traversing serious economic difficulties: Unicredit in Italy, BNP Paribas in France, and Banco Bilbao in Spain.

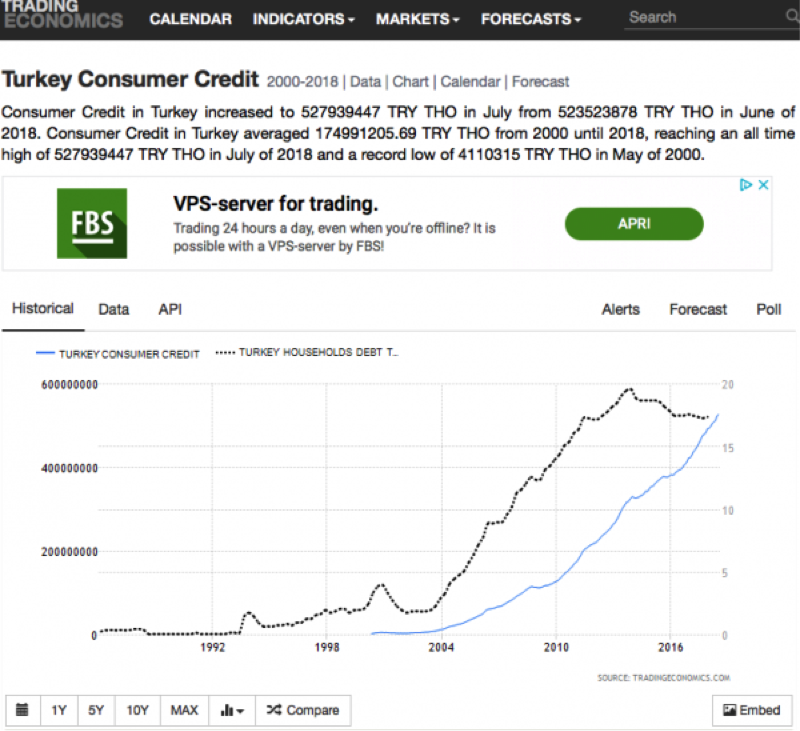

The indebtedness of Turkish businesses and private citizens is sufficiently serious as to make comparisons with the American financial crisis of 2006-2008 not unreasonable.

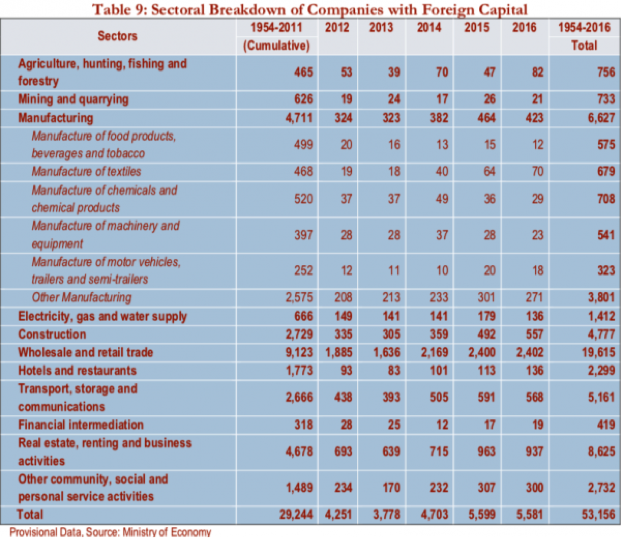

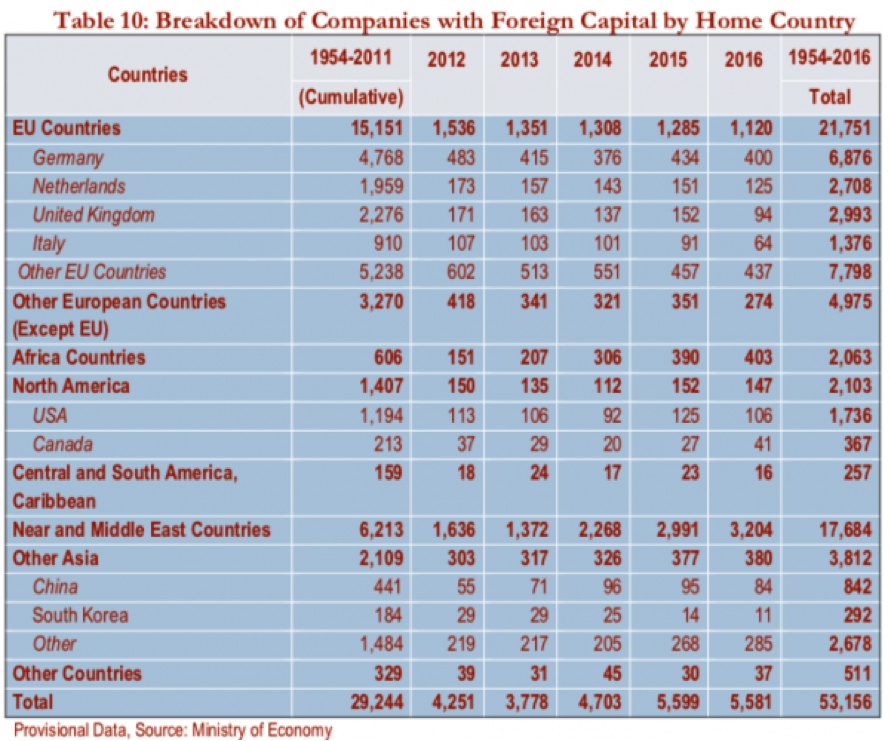

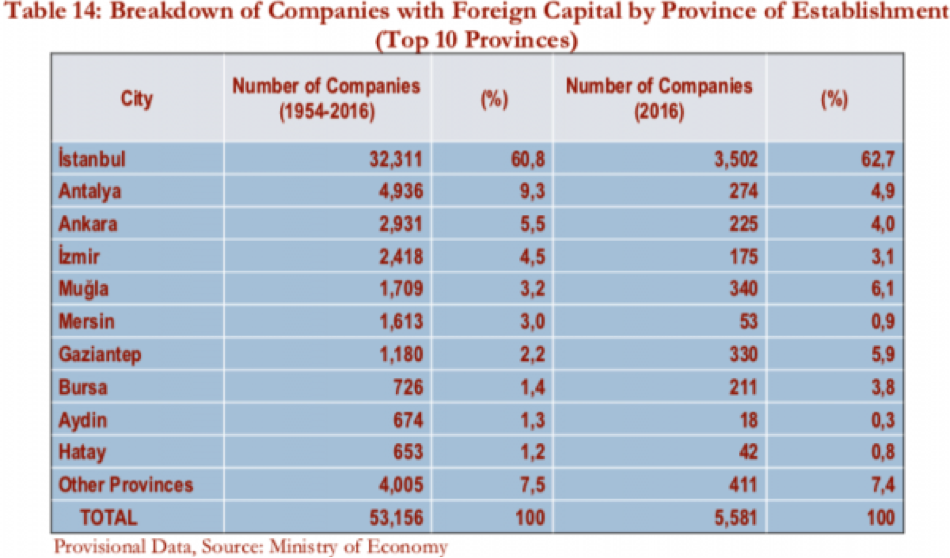

If we look at the table above, we notice that the sectors where easy credit can create rapid short-term growth (wholesale and retail, hotels and restaurants, real estate, financial intermediation, etc.) constitute a major component of foreign investment in the Turkish economy. They are followed by the manufacturing sector, which naturally involves a high level of energy consumption.

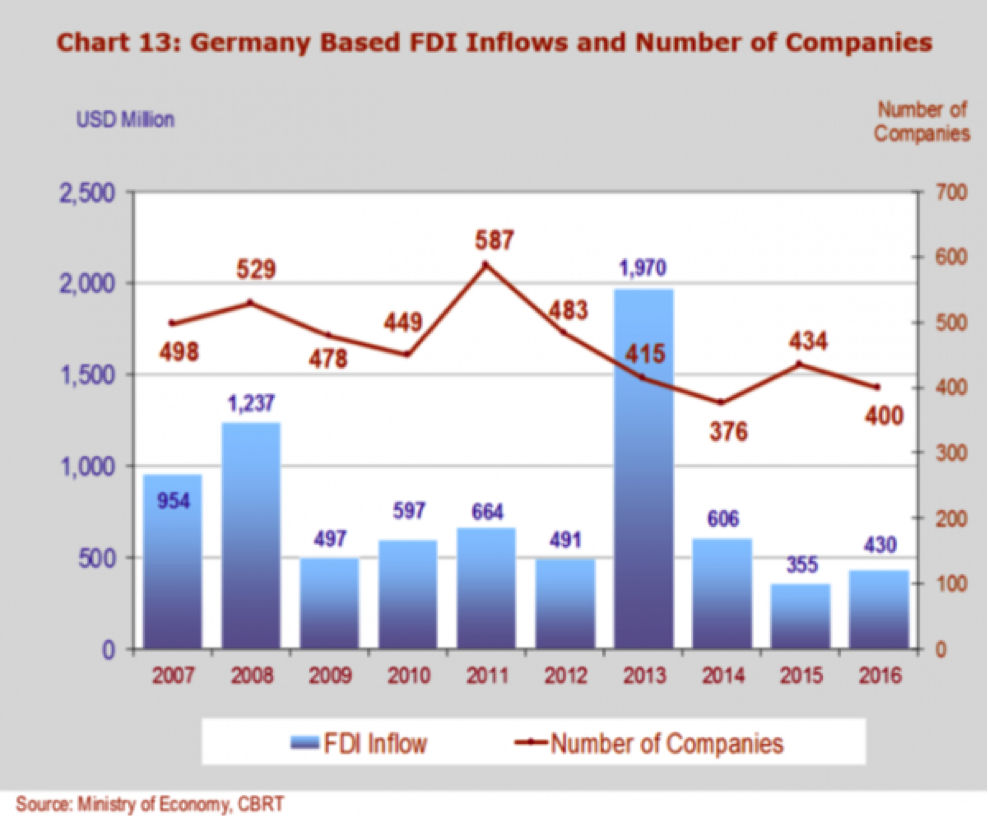

The Turkish banks are exposed to foreign currency-denominated loans that Turkish businesses are now, with the collapse of the Turkish lira, finding difficult to repay. Three of these banks are owned by the three European banks mentioned above, and there are also many other European banks with exposure; judging from the percentages seen in the table, German institutions figure here prominently as well.

It is claimed that the Turkish banking system faces about a 3% rate of bad loans. But numerous media sources report that there are additional restructured loans that might reach as high as 10%, a worrisome number. Passing now to European banks, Reuters reports that Banco Bilbao is exposed to the tune of 14%. Unicredit, and to be precise its stake in the Turkish bank Yapi Kredi, is under scrutiny of Goldman Sachs, who deems the Italian bank at risk due to Kredi being so heavily exposed in capitalization terms. BNP Paribas looks like it will have to take about 1.1 billion Euro in writedowns.

Where has the money that foreign and Turkish banks loaned or invested in Turkey gone? Private consumption – houses, cars, and consumer objects – has in the last 15 years become a giant bubble. The graph below, from this site, shows how Turkish household debt and consumer credit have grown. It isn’t difficult to see that the current Turkish crisis has clear underlying causes to be looked for in at least 15 years of “blissful” finance.

Domestic Politics and Society

On top of all this are ongoing attempts to set up Turkey as a beacon of moderate (Sunni) Muslim civilization. These have involved a number of choices in domestic politics that have aggravated popular discontent – above all, a growing emphasis on religious themes. Although Turkey is a secular state, religion nonetheless plays a fundamental role, and differences between peninsular and western Turkey (Istanbul) contributed to the clashes in Taksim Square. Those protests had their origin in concerns over real estate speculation, but they soon had a major social component as well. An overwhelming portion of the foreign investments went directly to Istanbul, given that foreigners tend to see it as an entirely European city, and therefore (rightly or wrongly) easily understandable by Westerners.

It is not hard to imagine how the populace of Istanbul has felt seriously betrayed by a series of choices by Erdogan, from the veil to prohibitions on alcohol use in the city. This “perception of betrayal” has created mounting tensions between what we can call secular Turkey and the steadily growing populist/Islamist Turkey, tensions that have led to fissures in both civil society and the military. In fact, the huge Turkish military apparatus has always been a shadow organization that protected (and checked) the secularist vision of Atatürk.

These tensions have grown steadily, culminating in the coup attempt against Erdogan a couple of years ago. Erdogan took advantage of the situation, carrying out a series of military and legal actions reminiscent of the Stalinist purges, with thousands of (civil and military) public employees fired and arrested, and the upper echelons of the army lopped off and “cleansed.”

Turkey’s Stubborn Sovereignism

Despite Erdogan’s recent lavish praise of European heads of state from Merkel on, relations between Turkey and other EU members – particularly Germany – have deteriorated. Looking at the graph below showing German investment in Turkey, it isn’t hard to see why.

It is against this backdrop that Erdogan made his latest series of sovereignist declarations. He invoked Allah and the salvation of the nation and asked the Turkish people to convert foreign currency into lira (or gold and other precious metals). These statements have sown panic among the by now highly stressed population, and immediately became a perfect refrain for the (pro-globalization) European media. Unsurprisingly, the banks (particularly Western ones) are terrorized and are trying to extract what they can from the wreckage. Financial institutions are gripped by the fear that Turkey and its businesses and private citizens will be unable to repay their debts.

That Erdogan is sovereignist is hardly a secret. To say that the cause of the Turkish crisis is his sovereignism is a rather one-dimensional interpretation. A more accurate summary is that the crisis is due to a pattern of financial speculation and careless investment that is particularly reminiscent of the American financial bubble that in 2006-2008 completely collapsed.

Thank you to NC.

I can vouch for the easy, short-term and property related credit provided by European banks. The market became very competitive. My manager and veterans, all of whom had been recruited from school by Midland Bank in the 1950s and 1960s, said that “credit had become as cheap as chips” or “commoditised” and it felt like Latin America in the 1980s.

From 2003 – 6, one of the territories I supported from HSBC in London was Turkey. We supported two dozen other markets in Latin America, eastern Europe, the Balkans, South Africa and central Asia. It was cheaper to fund from London (HBEU) than use HSBC Turkey (HBTR) and other local subsidiaries. The hot money was flowing into markets that are also suffering now.

HBTR’s own loan book grew so much, it began deploying staff in London and Dubai to help service clients and hasten the admin. HBTR set up two securitisation programmes domiciled in the Caymans. Some of the loans made by HBEU were rolled into these programmes.

The other odd aspect of the lending was collateralised loans from Turks sheltering their money in Panama and Caribbean islands. HBEU would take a deposit from a Panama / Caribbean entity and lend it to a Turkish company owned by the same individuals behind the Panama / Caribbean entity. Lots of cross firings and guarantees, too. Many deals made no sense, but we turned a blind eye.

Why does this not surprise me? I am asking myself how BBVA (about 70 billion exposure in Turkey) turned a blind eye to the risks of foreign currency loans. I am a BBVA client because I concluded during the financial crisis that it was a little bit more serious banking institution compared with the rest of spanish banks and cajas. Bad conclusion indeed!

But if one has to believe in some kind of spanish press, the turkish BBVA malaise is not to be blamed on bank managers since it is all Erdogan’s fault (link in spanish). This is the kind of stupid, arrogant, FMI-like stupidity than contaminates many supposedly superior and economically knowledgeable western press outlets. We are constantly feed with such shitty coverage.

This is another way to say thanks to NC for providing much better contextualised analysis.

Most really don’t understand just how prevalent hyperinflation has been in the past century, you wouldn’t know unless you were involved in forex or followed currency exchange rates, it’s there in plain sight, but it goes unmentioned…

Turkey (and Mexico) went through extended periods of hyperinflation that was ruinous to both countries, and it’s akin to a financial disease that never leaves even if you lop of 3 or 4 zeroes from the old currency and issue new money, the damage is done.

There is also an expensive military component to Turkey’s problems. Using a recycled Ottoman foreign policy and remembering past territories, Turkey is attempting to occupy parts of both Syria and Iraq while using their fight with the Kurds as an excuse. And they don’t plan on leaving voluntarily either. Even as long as two years ago, Syrian school returning to school in al-Bab were handed a new textbook called “Türkçe Ögreniyorum” – “I am learning Turkish”. Turkish lessons, Turkish signposts, Turkish-trained police and a Turkish post office as well as Turkish hospital administrators have all turned up.

None of this would come cheap and neither Syria or Iraq will give up parts of their countries and people to the Turks. It was OK when Turkey was getting all those convoys of lovely Syrian oil from ISIS but the Russians turned that little operation into toast. There would be a constant outflow of Turkish lira to pay for their military presence as well as paying the Jihadists on their payroll with little to show for it. This is not even considering the constant bleeding of fighting a war against the Kurds in Turkey, Syrian and Iraq. Turkish support will not last forever with these foreign ventures and the Turkish people may eventually say to Erdogan: “Well, this is another nice mess you’ve gotten us into”.

Anyone else read Adam Tooze yet?

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/36950522-crashed

I am about 2/3 through and can’t recommend it highly enough.

This week he published the ‘missing chapter’ from his book. As yet I have not had time to digest it but it is likely relevant here.

https://adamtooze.com/2018/08/19/framing-crashed-4-the-turkish-crisis-the-missing-chapter/

I’m reading it. Was initially cautious given the author’s acknowledged ideological and cultural biases. No need to fear, it is a great, and I think, fair read. i may not agree with all his views, but so far, half way into the book, he is a fair and independent thinker. My take, anyway. The topic itself is great! And he’s a good writer. Meticulously (I think) researched and documented, I give it a strong endorsement.

Sorry if this is a repeat – my first attempt went missing.

Has anyone read Adam Tooze yet?

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/36950522-crashed

I am about 2/3 through and can’t recommend it enough.

He just published the ‘missing chapter’. I have yet to digest it but it seems relevant here.

https://adamtooze.com/2018/08/19/framing-crashed-4-the-turkish-crisis-the-missing-chapter/

I just read the Tooze “missing chapter.” It’s really excellent – thanks for the link, which I’ve passed along to numerous friends who follow developments in the region.

I appreciate hearing about Tooze’s book. I visited his website and blog page. His blog page is full of interesting essays and references to pdfs in on a range of topics. I thought the essay “America’s Political Economy: Inequality in 2D and 3D” [https://adamtooze.com/2018/06/13/americas-political-economy-inequality-in-2d-and-3d/] added some depth (pun intended) to the many discussions of inequality here. There is quite a bit of other interesting material posted.

Surprised no mention of US sanctions as a precipitating factor in the current crisis.

Also no mention that Erdogan believes the West was complicit in the attempted coup.

We have Richard Werner’s “Princes of the Yen” as a step-by-step guide to quickly grow your national economy. If Turkey empowered its central bank governor in that way, it might yet escape the natural consequences of its acts.