Yves here. Depressing to see that Labour subscribes to mainstream, as in neoliberal, economics, which means they are committed to continuing austerity.

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

I mentioned yesterdaythat James Meadway, who is John McDonnell’s chief economic adviser, had dismissed modern monetary theory out of hand at the weekend, in the process committing Labour to the austerity agenda which, right now, is pretty much the only known alternative in town.

I was amused, and not surprised, to note that Jonathan Portes waded into the debate on Twitter, saying in response to a tweet that circulated my work to a number of well-known economists:

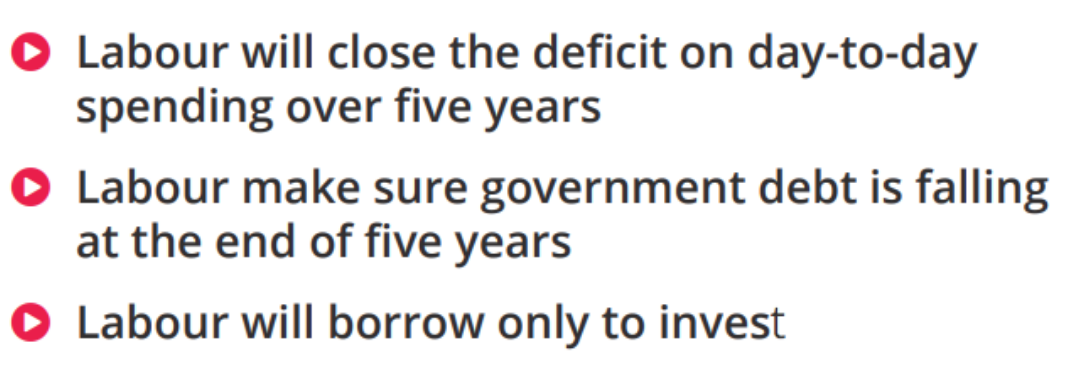

So, the people (Jonathan Portes and Simon Wren-Lewis) who wrote Labour’s fiscal rule that promises balanced current budgets and borrowing only within the constraints of the market (however pro-cyclical that constraint may be, most especially given their vehement dedication to central bank independence), and so guaranteed that Labour will remain committed to the austerity policies that George Osborne and Philip Hammond have been noted for, are also committed to denying that the state may use the very obvious power it has to create money for any purpose bar bailing out banks, as most quantitative easing did.

Just to make sure we know what we’re talking about this is Labour’s Fiscal Credibility Rule, written by Jonathan Portes and Simon Wren-Lewis and adopted by John McDonnell:

Candidly, it’s hard to differentiate this from anything produced in the Brown / Balls era. It is pure neoclassical economic thinking. I think that suggestion, much discussed Simon Wren-Lewis on Twitter yesterday, simply to dismiss the suggestion from someone not familiar with economics that it was neoliberal, needs to be explored.

First, to pick a theme from the blog post of Simon’s that Jonathan Portes highlighted, the macroeconomics on which this ‘rule’ is based has its roots in microeconomics. As Simon has accepted, this is in many ways the difference between neoclassical and MMT economic thinking. But the difference is not minor. The microeconomics referred to makes some pretty major, and almost invariably incorrect, assumptions. I am, of course, aware that these are relaxed on occasions, but the fundamentals remain in the macroeconomics based upon it. In particular, there is an assumption that markets can allocate resources efficiently. And that when doing so they eventually use all available resources, even if it takes time for them to correct to external shocks so that resources are used in this way, with full employment being re-established, as the norm. The model, then, assumes government ultimately need not intervene in markets to create this outcome. Unsurprisingly, as a result, the modelling suggests that there is no reason for the government to run a deficit on day-to-day spending because the markets can be relied upon to sort things out. That there is no evidence to support this assumption is apparently beside the point for Jonathan; that’s what the model says (even if that’s the inevitable outcome of the assumptions made and not the consequence of any observed reality) and so that is what the rule must say as well.

There are also major problems with the macroeconomics based upon these assumptions. In particular, taxation does not play a proper role within it, and nor, come to that, does money. That is because money is simply assumed to transfer value, as does much of tax, but given that we know that is not true of finance, and that taxation plays a much broader role within the economy than this, this macroeconomics is inappropriate as a basis for determining any fiscal rule, for which it can have no answers. Again, then, this model is inappropriate for the task it is being asked to do: it does not address questions of fiscal balance but does instead assume them away, just as this fiscal rule does.

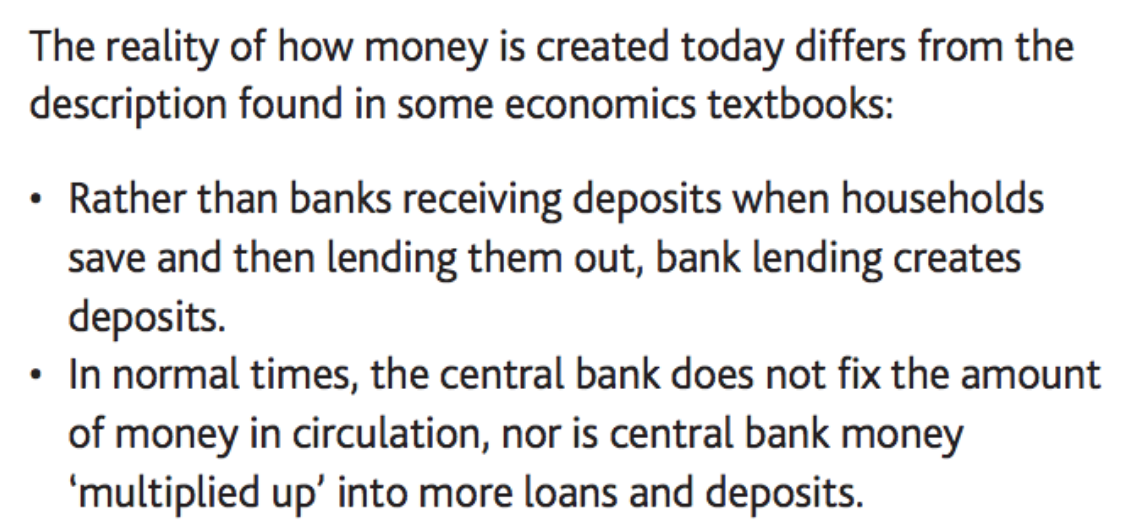

Thereafter the microeconomic assumptions underpinning this macro gets what it says about money wrong. As the Bank of England had to say in 2014:

The reference to ‘some’ economics textbooks might, appropriately, be read as referring to the vast majority of neoclassical textbooks.

This means it is not true that, as Simon claimed, that the main difference between neoclassical theory and MMT was that the former relies upon monetary policy to control inflation and the latter of lies upon fiscal policy to do so, although that is undoubtedly true, and it so happens that because monetary policy is dead in the water only one of the two can now work. Instead, the real difference is much more fundamental.

Most especially, the differences come at three levels. First, MMT looks at the world from a macro perspective, not a micro one. In other words, it is macroeconomics. That might make it fit for the purpose of managing the macroeconomy.

Second, MMT ascribes appropriate functions to tax and money that actually recognise the way in which they really do play a role in the economy, and which, in the case of money fits with the Bank of England’s description, noted above.

And third, MMT does not assume that the market economy automatically uses all resources available within the country, and nor does it assume that the market delivers economic balance at full employment. Given that these assumptions reflect reality, unsurprisingly it suggests a somewhat different approach to macroeconomics to a model based upon inappropriate macroeconomic assumptions. In particular, it presumes that the state might have a role in creating full employment, and might need to spend to achieve that purpose, and what is more it appreciates that in the process all that it is doing is creating the capacity to pay any necessary tax to control inflation, which is a desirable objective of macroeconomic policy, but one that is not nearly as important as delivering sustainable well-being for those who wish to work, and those they wish to support, within a country.

Jonathan Portes might be with James Meadway in rubbishing MMT then. I’m willing to believe that what he says is true in this regard. But what it also means is that he is willing to promote macroeconomics that is based on inappropriate assumptions and models, that cannot say anything useful on fiscal balance because it is assumed that there is nothing to say, and makes balancing the government’s books more important than any other economic priority. I’d suggest that’s getting most things wrong, from the basics to the assumptions to the objectives to the policy prescriptions. But no doubt Jonathan Portes will handle the criticism by dismissing me as he did his co-author Howard Reed, which I am sure he was chuffed about.

Richard Murphy, please continue to make your valuable contribution to illuminating the policy options that the UK Government has. Persistence and patience are extremely important to achieving long-term political goals. The people who deride your contributions are doing what they think is necessary to protect their position. They will be proven wrong provided that enough people continue to make cogent and accessible arguments based on an accurate understanding of the fiscal policy options available to a government that issues an unpegged currency.

The IMF predicted Greek GDP would have recovered by 2015 with austerity.

By 2015 it was down 27% and still falling.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

The “private debt” component was going down with deleveraging from a debt fuelled boom. The Troika then wrecked the Greek economy by cutting the “public debt” component and pushed the economy into debt deflation.

Richard Koo had to explain it to the IMF, even though it’s very straight forward (see above).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

The graph is at 15.30 mins. for the UK and we are still paying down debt from that debt fuelled boom and in a balance sheet recession.

Our Government is keen on austerity when they need to maintain the money supply to keep debt deflation at bay.

Simon Wren-Lewis has been in parallel with MMT in arguing that austerity was the wrong thing to do in the aftermath of the financial crisis. So why would his fiscal rule disallow fiscal stimulus during recession?

Murphy should have included the lines directly below “Labour will borrow only to invest”. The lines say “When the Monetary Policy Committee decides that monetary policy cannot operate (the “zero-lower bound”), the Rule as a whole is suspended so that fiscal policy can support the economy. Only the MPC can make this decision.”

This is far from MMT, but it isn’t “austerity is the medicine for recessions” either.

Yes it is. Monetary policy is ineffective in addressing slumps, yet that is what Labour wants to use until it can’t be used any more. Multiple contacts with separate routes into the Fed say the Fed will never admit it publicly, but privately circa 2013 pretty much everyone was convinced the super low interest rate experiment had failed and they needed to back out of it as rapidly as they could, since they wanted interest rates at at least 2% so as to have positive real yields plus somewhere to drop them (recall prior to the Greenspan put of the dot-bomb era, the Fed would drop rates low for only one quarter and then re-normalize them).

Low interest rates stimulate business activity only in businesses where the cost of money is the biggest cost of doing business, such as banking and financial speculation. In other businesses, the cost of funding can constrain business expansion, but an owner ins’t going to say, open a new store just because money is on sale. He’ll expand if he sees a commercial opportunity.

Super low rates increase asset prices, which as we have seen in the US has the effect of increasing inequality by among other things increasing housing costs (see the drop in homeownership and the increase in rents). Economists have now concluded that higher levels of inequality are bad for growth.

If monetary policy is ineffective in addressing slumps like you said, then interest rates will hit the zero lower bound quickly. Accordingly the fiscal rule then gets suspended “so that fiscal policy can support the economy”. This is plain as daylight not austerity at all costs!

Maybe Labour should simply announce that they will not adopt any policy with a proven track record for trashing economies and racking up massive debts. That would put paid to austerity right then and there. This thing where countries go back again and again to do things that don’t work is exasperating. It reminds me of something that I heard once. You want to know the difference between a rat and a human in a lab maze where one corridor leads to a dead end? The rat will stop going down that corridor.

I do find it depressing and really it is my biggest issue with the party right now (I am a paid up member FWIW).

I think the comment from Jason above is somewhat fair. But I am a long way down the MMT path now and really do want to see something far more radical on economic policy.

That said, the political situation re the UK MSM and the accepted public narrative does require careful navigation.

So how, again, did the neoliberal machinery come to dominate policy and power? There’s these wise people, speaking gently and with cautious phrasing and respectful tone and so forth, telling us that macroeconomic insights and prescriptions ought to be the correct basis and fundamentals for unpegged national economies. How do those principles and practices he forced onto the political economy, e way the neoliberal straitjackets and garrotes have been forced onto it to date?

This is not some rarified mutual-respect-between-peers academic debate. The polite tone and tenor of the the minatory and hortatory offerings of folks like the author don’t seem to me to be likely to lead to “change” in what needs to be seen as a battle, with unconditional victory as the only acceptable outcome.

That’s surely how the ruling elite is operating, catalyzed by calls to arms like the Powell Memorandum and confirmed by folks like Warren Buffett, he of “Of course there’s class warfare, and my class, the rich class, is waging it. And we have largely won.”

It’s interesting to contrast to http://thehill.com/homenews/house/390898-dem-leaders-embrace-pay-go

I.e. it’s all part of the resistance don’t you know. “Now that Trump is off the reservation regarding pay-go, we’re going to make it a centerpiece.”

But the same can’t be said for Labour in the UK. It’s not like the Tories are off the reservation regarding pay go (or balanced budgets, aka austerity). In which case, why drink the same kool aide? Is it the authority mystique?

If I didn’t know anything about Corbyn, it would suggest he’s getting ready to pull an Obama, “I would love to do xyz, but I have this gun pointed at my head.” [A gun that Obama himself was holding.] Maybe Corbyn is letting this issue lay fallow as he fights on other fronts? Who knows. But Corbyn would find that fighting and winning the debate on fiscal spending is the one and only battle, really. Everything else flows from that.

“First, MMT looks at the world from a macro perspective, not a micro one. ”

For me, this is at the heart of the matter. If your perspective boxes you into certain conclusions it’s hard to think any other way unless you change the perspective.

I had an orchestration teacher get me to lay out the Main Title score to Air Force One across the floor and stand on a chair to “see the big picture.” From that vantage point it was clear that Goldsmith was imitating old protestant hymns.

So, it would seem, are the current crop of political-economist policy makers; “Onward Christian Soldiers,” “A Mighty Fortress is Our God,” etc.

Not God, but similar. Neoclassical belief seems to be (e.g. in the Lendable Funds Theory) that Money is a force that comes to the Economy from outside and makes everything right, and equilibrated. Definitely a parallel.

When we come along and say that that force is really just something that we made up, of course they hate it.

Chaining itself to austerity, to Brexit, consuming itself over what seems to be a largely manufactured row over “anti-semitism”, which appears meant to hide a bigger row between the Tory-lite Blairites and more traditional Labour, the Party seems bent on neutering itself in order to snatch defeat out of the jaws of victory.

IMO, fighting for such things as preserving the NHS, social housing, basic regulations (pensions, building safety standards), working railways, university grants (instead of rent-seeking loans) would be healthier for the UK. They are concrete issues, they affect daily lives, and only government can do them. That would give the party purpose and the opportunity to lead Parliament.

It’s about time to retire this myth of there being a Fiscal Policy and a Monetary Policy, and with the the so-called “independence of the central bank from the treasury.”

The difference between them is that with fiscal policy money can go to the poor. With monetary policy money only goes to the rich.

Too bad. The left shooting itself in its own foot is … disturbing. I’ve heard similar dismissals of MMT from Bernie Sanders too (although, in fairness, Bernie hired MMT’s Stephanie Kelton).

I’d argue this is more of Boss Tweed’s motto: “I don’t care who people vote for as long as I can select the candidates.” It won’t matter who is in office, ordinary people will be screwed. Mark Blythe argues that one can either have a gold standard (with its built-in deflationary bias) or democracy, not both. I’d add that one can either have MMT and its policies (e.g. Job Guarantee) or an oligarchy. Democracy with austerity is simply self-deception (see the Princeton Study demonstrating the U.S. is an oligarchy). The problems are systemic, not amenable to individual solutions. That’s what that “macro perspective” handles.

Labour risks making itself obsolete, too. After all, Dilma Rousseff adopted austerity despite her “left-ish” leanings, and look what it got her.

Adam said it well.

I wonder if Mitchell would be so optimistic re Brexit if he assumed neolib austerity would be continued.

Meadway, Portes, and Wren-Lewis’s blinkered obsession with neoliberal austerity reminds me of something in today’s Michael Hudson autobiography:

“One of the top investment analysts for the Royal Bank decided to become the head of personnel. He said he thought that it’s a personality problem that economists can’t understand how the world works, that there’s a particular kind of dumb person that becomes an economist. It’s a kind of autism, of thinking abstractly without a sense of economic reality.”

Richard Murphy is so good he just leaves me grinning. These pols are such economic clodhoppers it’s like lambs to the slaughter. Jacobin had a good history on some of this nonsense yesterday. But nothing so hard-nosed and factual as Murphy.

You’re right the politicians sit there in their debating chambers receiving a nice fat salary and can’t even be bothered to ask themselves how the country creates its money. A blight on society is the appropriate term for the majority of them!

http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2018/07/25/the-treasury-admit-that-tax-does-not-fund-government-spending-as-modern-monetary-theory-suggests/

https://www.carolinelucas.com/latest/financial-times-mark-carney-boosts-green-investment-hopes

One graph from the MMT people of the US, and one from a central banker, Richard Koo, of Japan.

(He worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York).

They both show how dangerous reducing the deficit is and both show a Government surplus precedes financial crises.

This is the US (46.30 mins.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ba8XdDqZ-Jg

There are three terms that sum to zero.

If the Government is going positive, something else is going negative, which is the private sector. Clinton reduced the Government deficit and drove the private sector into debt leading to the dot.com bust.

Richard Koo shows the flow of funds within the Japanese economy, which sums to zero (32-34 mins.).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

(You may note he expects other central bankers to be familiar with this chart.)

It’s the same as the MMT chart, but the private sector is split into the corporate and household sectors. It’s something central bankers use themselves.

Richard Koo’s video shows the Japanese Government ran a surplus just before the Japanese economy blew up. It’s a zero sum equation, and so if the Government goes positive, something else has to go negative, which is the corporate sector.

The UK has a trade deficit and its best the Government covers that with its own deficit, rather than drive the private sector into debt (see above).

I’m thinking the trigger for Japan’s recession was an inverted yield curve, just like what happens in the US. I tried to piece together a view of their short term rates and 10Y rates, see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=kO9n , but the 10Y data only goes back to 1989 so it’s hard to go further back to confirm the pattern. Anyways, it looks like their central bank raised short term rates above their 10Y rate, starting 1989. Which would have been equivalent to taking the punch bowl away for their bubble economy.

Here’s a comparable graph for the US: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=kO5K

It was just a massive real estate bubble that burst.

Seeing Richard Koo’s chart it seems like it was the corporate sector that was taking on most of the debt.

Is the formulation of “will borrow only to invest” really so bad? A lot of MMT could be hidden under that there camouflage netting!

The UK is chronically starved of investment (transport, healthcare, defence). Moreover, the boundary between capital and current spending is porous – and I could make it more porous if I used the PFI tricks of New Labour in reverse and cheerfully paid contractors over the odds (who cares, it is MMT and it would buy them off politically) for serviced infrastructure rather than empty buildings.

Ah, but they said borrow? So what? Either borrow gilts until the market pukes and then monetise them (bold but political suicide, possibly) or capitalise a public investment bank with equity and borrow from yourself. Mustn’t admit that monetary and fiscal policy are the same thing, must we? The left can play the shell game too. See also the Metalgeschellshaft and Shimomuran economics.

We have the same problem with the NZ Labour government, who are required by statute to balance the budget except during periods of recession. In order to do any kind of deficit spending, they would need an exemption from Treasury, which they wouldn’t get as Treasury is staffed entirely with captured economists. They are so far down the neoclassical rabbit hole that they regularly make nonsensical policy recommendations that are ignored by both major parties, but it doesn’t harm their credibility on austerity, as they are simply reinforcing what most people intuitively believe.

The only other alternative would be to change the law. This would require widespread public understanding of MMT style principles and the problems with austerity as a prerequisite, or it would be political suicide to try. Unfortunately I see no evidence that the current government is preparing the ground for this – in fact they seem to be well on board with the whole austerity mindset.

Really helpful analysis! I’ve read Wren-Lewis before trying to assess where he fits politically – now I know! His post on MMT reveals so much about himself. “I like a lot about MMT as a set of ideas.” That’s right; and their advocates must always be polite and only interested in “scientific discourse”. And of course while he’s helping out write Labour’s austerian fiscal rule, a politically charged and empowered act, he lectures about the dangers of “schools of thought” like MMT becoming too “political”. Does it really matter if he’s “attracted to the idea of some kind of version of a Job Guarantee” if it’s the last thing he’d ever actually advocate for?

Correct and for Wren-Lewis to argue that a premium must always be paid to the few and no other body for our “settling-up means” is unethical!

It is absolutely stupid to expect any kind of new economic thinking from ANY economist who hasn’t disparaged neoclassical and neoliberal economics and instead has a career in it. Its about time medway and the new economics foundation was brought out about this. Read mirowski or any other great economic thought historian and it becomes obvious! I hope people aren’t surprised by this behaviour.

Simon Wren-Lewis responds, and I think he’s got the better argument than Richard Murphy.

https://mainlymacro.blogspot.com/2018/08/labours-fiscal-rule-is-progressive.html

Excerpt:

“The bottom line is that Richard tries to suggest that you could have more public spending under an MMT type assignment compared to Labour’s fiscal rule. That is also completely wrong, and if anything the opposite would be true. Suppose Labour comes to power in 2022, and nominal interest rates by then are at 2%, and inflation is steady at target. Labour are pledged to substantially increase public investment spending (which is outside the rule), which will put upward pressure on demand, at least initially. That would mean under a conventional assignment interest rates would rise to prevent inflation. But in an MMT world that wouldn’t happen. So in an MMT world how do you stop inflation rising? Either current spending would have to be cut, or taxes increased.

There is only one way that public spending for given taxes could be higher in an MMT world compared to Labour’s fiscal rule, and that is if inflation was not controlled at all. That is not what serious MMT economists would recommend.“