This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1287 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser and what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, increasing our staffing, also known as burnout prevention

Yves here. One factoid to file away: rating agencies almost never downgrade bonds before Mr. Market does, as the securities will be trading at or near a level consistent with a lower credit score before the agencies lower the rating.

By Don Quijones, of Spain, the UK, and Mexico, and an editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

But outside Italy, credit markets are sanguine, and no one says, “whatever it takes.”

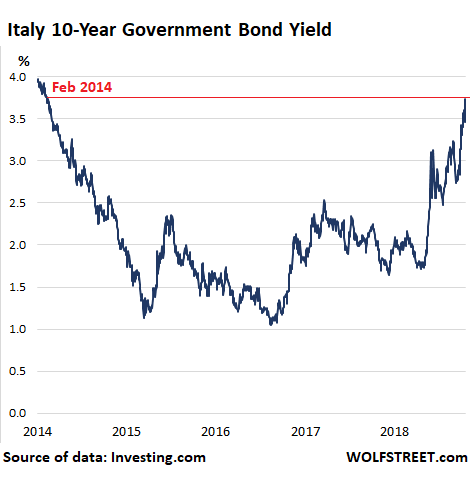

Italy’s government bonds are sinking and their yields are spiking. There are plenty of reasons, including possible downgrades by Moody’s and/or Standard and Poor’s later this month. If it is a one-notch downgrade, Italy’s credit rating will be one notch above junk. If it is a two-notch down-grade, as some are fearing, Italy’s credit rating will be junk. That the Italian government remains stuck on its deficit-busting budget, which will almost certainly be rejected by the European Commission, is not helpful either. Today, the 10-year yield jumped nearly 20 basis points to 3.74%, the highest since February 2014. Note that the ECB’s policy rate is still negative -0.4%:

But the current crisis has shown little sign of infecting other large Euro Zone economies. Greek banks may be sinking in unison, their shares down well over 50% since August despite being given a clean bill of health just months earlier by the ECB, but Greece is no longer systemically important and its banks have been zombies for years.

Far more important are Germany, France and Spain — and their credit markets have resisted contagion. A good indicator of this is the spread between Spanish and Italian 10-year bonds, which climbed to 2.08 percentage points last week, its highest level since December 1997, before easing back to 1.88 percentage points this week.

Much to the dismay of Italy’s struggling banks, the Italian government has also unveiled plans to tighten tax rules on banks’ sales of bad loans in a bid to raise additional revenues. The proposed measures would further erode the banks’ already flimsy capital buffers and hurt their already scarce cash reserves. And ominous signs are piling up that a run on large bank deposits in Italy may have already begun.

It’s not just the banks that are panicking; so, too, are Italian insurers which could face having to shell out more in advance taxes on their premiums as a result of the new budget, assuming it is ever given the green light by Brussels. “We need to be very careful dealing with these issues … because we are one of the pillars of the national system,” the chairman of Italy’s biggest insurer, Generali, said on Tuesday.

Global investors also have big reasons to worry. Italy’s government faces an eye-watering €270 billion worth of bond redemptions in 2019 alone. With interest on Italian government debt rising to its highest level in five years and its biggest margin buyer of the last three years, the ECB, exiting the market, it’s looking like a tall order.

The Bank of Italy is afraid that a vicious cycle is forming over the country’s debt costs. If market tensions don’t ebb, it warns, interest spending could surge above government estimates in 2019-20. Interest expenditures had fallen to €65.5 billion in 2017 from a high of €83.6 billion in 2012, helped along by the ECB’s buying of sovereign bonds as part of its QE program.

In 2012 the yield on Italy’s ten-year bond smashed through the 7% mark. Markets were in a frenzy. And then, Mario Draghi gave his “whatever it takes” speech and unleashed the world’s largest ever QE program.

But that program is ending this year, and at some point next year, the Eurozone’s benchmark interest rates are supposed to begin the long arduous path toward “normalization,” which makes the timing of this gargantuan showdown between Brussels and Rome even more auspicious.

The new big fear is that this month, either or both, Moody’s and S&P, will downgrade Italian debt two notches into junk territory. The potential implications of such a move, not only for Italy but for the European project as a whole, are so huge that many market players are discounting it as a possibility altogether.

“A downgrade to junk could trigger a full-blown (euro zone) crisis,” saidNicola Mai, a portfolio manager at PIMCO, the world’s largest bond investor. “…Which is why I don’t believe the agencies will do it, I don’t think they will want to be the ones causing a crisis in Europe.”

Iain Stealey, a fixed income portfolio manager at JP Morgan Asset Management, concurs. “It would be a very, very big decision, just given the size of the Italian bond market; it makes up something like a fifth of government bonds in the euro zone,” he said. In other words, contagion would spread across the Euro Zone like wildfire.

For the moment, however, that’s not happening. Whereas at the height of the Euzo Zone’s sovereign debt crisis Italy and Spain’s bond yields moved virtually in tandem, today a gulf has opened up between the two.

Since suffering political turbulence in 2016, Spain’s fortunes have diverged from Italy’s. The Catalonian crisis has deescalated. The new minority government, while perilously fragile, is staffed to the rafters with former senior eurocrats who can be counted on to take orders from Brussels. According tothe FT, the country is even regarded by some investors as “semi-core,” in light of its strong economic growth, structural reforms and credit rating upgrades.

That may be pushing it a little. But it’s not just Spain that’s weathering the tide. Former crisis-country Ireland’s 10-year yield is just below 1%, while Portugal’s 10-year yield at 2.04% remains near historic lows — nothing compared to the wild gyrations it saw during the sovereign debt crisis when at one point it had spiked to 16%.

That the peripheral Eurozone bonds are not moving in sync with Italy’s this time might seem to suggest, as the FT posits, that investors do not regard Italy’s crisis as an existential threat to the Eurozone. That may be the best-case scenario — given how interconnected the Eurozone is and how large a footprint the Italian economy has. But if it plays out that way, and contagion remains contained, there may be no rescue forthcoming for Italy, just as the ECB’s Italian Chairman Mario Draghi warned last week. Of course, if Italy’s government backs down and agrees to play by Brussels’ rules, that may change, but for now there’s no sign of that happening. By Don Quijones.

The ECB has hired BlackRock, “a market power that no state can control anymore.” Read… Why’s the World’s Biggest Asset Manager Advising the ECB on the Health of EU Banks?

Just another reason why the euro needs to be abandoned and the domestic currencies restored. This speculative ‘spike’ would not be allowed to exist had Italy its lira. Italy has no real central bank, has no sovereignty and like Greece, will be crippled forever by the EU bureaucracy. The German deutsche mark (otherwise known as the Euro) is intentionally under priced in order to support German exports which at 10 percent of GDP are the highest in the world.

I believe DB’s chief economist has a better take:

Yes, there’s little to no chance of that happening. The two loonies at Italy’s helm are selling the italian equivalent of “a change we can believe in” and “make America great again” and need the additional public debt to keep the charade going. They are all about public perception and approval (and are very good at that, to the point that other parties are now reduced to near insignificance) and backing down would diminish their standing among the italians, so I don’t see it as a possible outcome. We’re going full in against everyone no matter what.

Yves, you have been saying this since 2008:

debts that can’t be repaid, won’t be.

The european project looks shaky and the euro very soft on this news. The Greeks should have left, but were found wanting a pair at the final moment. The Italians have seen what happened to Greece as a result – all so German and French (mostly) bond holders could be made whole

The whole arrangement is a ‘pig sty’.

The idea of a Europe and a working currency to support it only works if each country gives up its sovereignty entirely. This never happened and that is why the Euro will not be around for ever in its current form.

Eventually, someone is going to take a haircut. Whether it is the banks or the Italians themselves… prolly the latter.

I always hesitate to give people investment advice, esp. in this place, but I would not have one Lira in an Italian bank. Not safe.

Yanis Varoufakis was opposed to having Greece leave the euro and described why long form before becoming Minister of Finance.

We chronicled the 2015 negotiations in great detail and were alone in predicting that they would fail. We also described why leaving the euro would not happen because Greece would suffer even more damage than at the hands of the Troika. First, the majority of its debt is under English law and could not be redenominated into a new currency, so the big benefit of leaving the eurozone in fact would not apply. Second, as we have described at considerable length, it is impossible to launch a new currency in anything less than three years, which realistically is more like five or six. It would take the better part of a year merely to print a new currency, refit ATMs to handle two currencies, and stock the ATMs. Introducing a new currency requires not just that Greek banks code their systems for an additional currency, but that all the other players in the payments system, which includes foreign banks and payment systems processors, do so too.

In the meantime, no one will take drachmas because their banks won’t accept them. You wind up where Greece was in July 2015 when the ECB largely shut down the Greek banking system. Greece started experiencing petrol shortages almost immediately, with fish rotting on the docks. It was on the verge of food shortages in less than three weeks when the sanctions.

Oh, and aside from tourism, none of Greece’s export sectors would benefit meaningfully from a cheaper currency. They can’t export more food (Greece is already not self sufficient in food). Several decent studies looked at this in depth.

Sometimes the only choices are very bad or worse. Leaving the euro is worse.

Not to mention Greece had some very troublesome issues pre EU and might have had something to do with the elites seeking EU membership, too sort it, albeit that does not vindicate the EU from offering credit and not accepting the risks associated post short term balance sheet profit – for a few.

An oldie but a goodie from 2/08 (before the Lehman collapse) these two comedians summed up what central banks and economists still have trouble comprehending:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=mzJmTCYmo9g

Hi Yves , can you if possible expand your coverage to Singapore? There’s not much good commentary available with most of it being the usual ass kissing by western governments and it seems to be quite an important player in the region in political and economic terms. It can make for very good reading for your readers as it’s a hybrid of highly statist but capitalist society with a veneer of democracy slapped on top. There’s a mall here for everything, even prostitution! Inequality is high but infrastructure is in great condition. Education levels are high but it faces productivity issues. It’s quite the standout and I think will help readers refine their thinking even further. A good point to start is joe studwell https://joestudwell.wordpress.com/?s=Singapore&submit=Search . His book Asian godfathers got banned in the country so he must be writing something good. Another one is pj thum, Oxford educated historian who was grilled unfruitfully by the govt for six hours for his take on a government crackdown a few decades ago. Here’s a good starting point for his work – https://youtu.be/2WS-GF3Iu7E

The solution to the Euro’s problem is simple: Kick Germany out of the Euro.

Germany has the resources to handle the transition, and their position as a parasitic exporter within the currency union, along with their disastrous economic policies are the biggest threat to the EU.