Jerri-Lynn here. This latest DeSmogBlog fracking post discusses the damage fracking is causing, by triggering earthquakes and contaminating water supplies.

For those who may have missed it, I also suggest you read this important September post, The Fracking Industry’s Water Nightmare: Injection Wells Damage Production Wells, Rising Disposal Costs Will Increase Industry Losses. It’s not necessary to read the earlier post if you only have time for the latest.

By Justin Mikulka, a freelance writer, audio and video producer living in Trumansburg, NY. Originally published at DeSmog Blog

The first known oil well in Oklahoma happened by accident. It was 1859 and Lewis Ross was actually drilling for saltwater (brine), not oil. Brine was highly valued at the time for the salt that could be used to preserve meat. As Ross drilled deeper for brine, he hit oil. And people have been drilling for oil in Oklahoma ever since.

Lewis Ross might find today’s drilling landscape in the Sooner State somewhat ironic. The oil and gas industry, which has surging production due to horizontal drilling and fracking, is pumping out huge volumes of oil but even more brine. So much brine, in fact, that the fracking industry needs a way to dispose of the brine, or “produced water,” that comes out of oil and gas wells because it isn’t suitable for curing meats. In addition to salts, these wastewaters can contain naturally occurring radioactive elements and heavy metals.

But the industry’s preferred approaches for disposing of fracking wastewater — pumping it underground in either deep or shallow injection wells for long-term storage — both come with serious risks for nearby communities.

In Oklahoma, drillers primarily use deep injection wells for storing their wastewater from fracked shale wells, and while the state was producing the same amount of oil in 1985 as in 2015, something else has changed. The rise of the fracking industry in the central U.S. has coincided with a rise in earthquake activity.

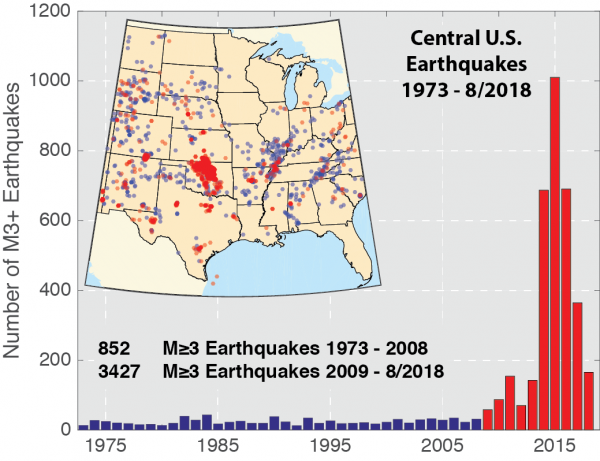

From 1975 to 2008, Oklahoma averaged from one to three earthquakes of magnitude 3 or greater a year. But by 2014, the state averaged 1.6 of these earthquakes a day. It now has a website that tracks them in real time.

[FAQ] Oklahoma now has more earthquakes on a regular basis than California. Are they due to fracking? https://t.co/itV3IvKoLp #OklahomaStateHoodDay pic.twitter.com/fXM2KCO10P

— USGS (@USGS) 16 November 2017

The state has been reluctant to link the two, however.

In 2015 E News reported that the oil industry in Oklahoma, including Harold Hamm, CEOof fracking giant Continental Resources, pressured state scientists to avoid acknowledging the link between earthquakes and drilling waste disposal: “Oklahoma’s state scientists have suspected for years that oil and gas operations in the state were causing a swarm of earthquakes, but in public they rejected such a connection.”

As DeSmog noted in recent election coverage, a top issue in the latest race for a seat on the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, the state agency that regulates oil and gas activity, was earthquakes caused by deep injection wells used to dispose of fracking wastewater.

Incumbent Republican Bob Anthony easily won that election, with financial help from Hamm and others in the oil and gas industry.

Wastewater Injection Wells and Earthquakes

Recently published research led by the University of Texas at Austin offers further insight into the link between fracking wastewater injection wells and earthquakes.

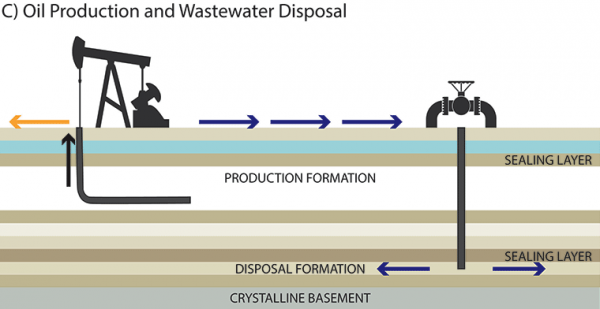

Injection wells for fracking wastewater work by pumping these fluids into geologic formations with porous stone that can act as storage areas. Theoretically, the water will stay where it was pumped.

Re-injecting produced water underground is not unique to fracked oil production. However, shale formations where fracking occurs require a different approach to wastewater, and their deep disposal wells in particular are linked to earthquakes.

During conventional oil production, produced water often is pumped back into the oil reservoir in a process known as “enhanced oil recovery.” This produced water replaces oil that has been pumped out of the reservoir, helping maintain pressure under ground and squeeze out even more oil in the future.

Due to the geologic nature of shale formations, drillers can’t pump produced water back into them after the shale is fracked and has produced oil and gas. Instead, they transport wastewater to areas where injection wells can be drilled into porous rock and the wastewater can be pumped down. Those injection wells can be either deep or shallow.

Unlike with enhanced oil recovery, these wastewater injection wells increase pressure below the surface, and when deep enough (along with other factors), lead to earthquakes.

Annual number of earthquakes with a magnitude of 3.0 or larger in the central and eastern United States, 1970–2016. The long-term rate of approximately 25 earthquakes per year increased sharply starting around 2009, which coincides with the surge in the fracking industry. Credit: U.S.Geological Survey

And yet not all fracking areas see the same level of human-caused earthquakes, and in this new paper from the University of Texas, researchers lay out the factors known to increase the likelihood that injection wells cause earthquakes.

In Oklahoma, they conclude those factors are threefold: produced water injection rates, cumulative volumes of produced water, and wells’ proximity to a layer of rock known as the “basement.”

In other words, this study reports that the likelihood of earthquakes will increase as companies pump wastewater into the ground at higher rates and at greater volumes, both of which increase the pressure of the water underground and the rate at which it is applied.

Proximity to the “basement” refers not to the actual depth of the injection well but how close it is to a typically deep and old layer of rock called the basement.

This study cited another recent scientific paper which pinned this well proximity to the basement layer as the main factor triggering seismic acitivity. This is most likely because, as the researchers wrote: “Large faults are expected to be more prevalent at greater depth, particularly in old, brittle basement rocks that have been subjected to different stresses over long times.”

The depth of the basement can vary greatly across the United States, but the deeper an injection well, the more likely it will be close to or penetrate this layer.

Earthquakes are a bigger issue in Oklahoma compared to other large U.S. shale plays, such as the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and Permian Basin, according to the University of Texas study, which says the major difference is that Oklahoma’s wastewater is injected into wells deeper and closer to the basement layer, while other, less-earthquake-prone shale basins have shallower injection wells further from this rock layer.

This raises an obvious question: If Oklahoma’s earthquake activity shot up as the state’s oil and gas industry began injecting fracking wastewater into deep wells close to the basement layer, then why not use shallower wells? Especially when considering cost of deep injection wells may be two to three times more than shallower wells, as this paper notes.

The fracking industry should be eager to save money and put to rest questions about earthquakes, right?

Unfortunately, shallow wastewater injection wells come with their own suite of potential problems.

Shallow Injection Wells More Likely to Contaminate Aquifers

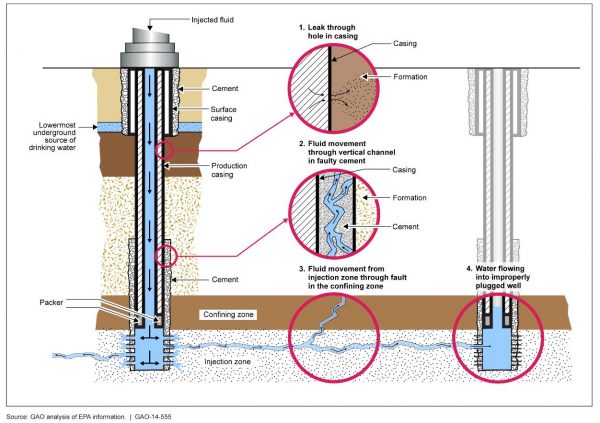

The closer a company injects fracking wastewater (and all the salts and pollutants that may come with it) to aquifers supplying freshwater for drinking and agriculture, the more likely those aquifers will be contaminated. In the recent University of Texas paper, researchers call out this increased likelihood in the country’s highest producing shale play, the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico.

Simply put, high pressure flows to areas of low pressure. Placing a lot of contaminated water under pressure below ground raises the risk of that higher pressure being released “through faults or fractures or through abandoned oil wells that have not been properly plugged.”

And if those pathways lead to an aquifer a community uses as a freshwater source, then there is a problem.

Credit: GAO review of injection wells

“There were over half a million oil wells drilled in the Permian Basin within the past century, with many abandoned or orphaned wells that could provide pathways for overpressured fluids,” wrote University of Texas researcher Bridget Scanlon and her colleagues in their recent paper.

How likely are fracking wastewater injection wells to contaminate aquifers? What is the scope of this problem? As with many aspects of the massive fracking experiment occurring across America, the answer remains unclear.

But the volumes of wastewater from the fracking industry are rapidly increasing and the main way to dispose of that water is via injection wells. And to reiterate, injecting produced water under higher pressures beneath the surface is unique to fracking disposal wells and is not characteristic of traditional oil production methods of wastewater disposal.

Oklahoma Already May Have Issues With Shallow Wells

Evidence in Oklahoma suggests some injection wells may be too shallow to avoid usable water supplies and many drinking water wells are drilled at depths placing them at risk of contamination.

A 2017 report commissioned by the Clean Water Fund found 18 injection wells drilled above the “base of treatable water” (BTW), or the lowest depth at which the state has identified subsurface water that is “in its natural state” and potentially useful for the typical range of human freshwater uses.

In addition to those concerns, the report noted that “6,844 domestic water wells and 175 public water supply wells draw groundwater from below the reported BTW,” which means injection wells could be drilled at similar depths as those drinking water wells.

The Oklahoma Corporation Commission challenged the findings, which were based on its own publicly available data that the agency called “faulty,” and said the 18 injection wells singled out were not injecting into underground sources of drinking water.

While the report did not provide a direct link to any contamination, it suggests the issue of shallow injection wells and drinking water supplies deserves further scrutiny.

The fracking industry is producing record amounts of oil, gas, and wastewater, meaning this problem of wastewater disposal isn’t going away soon and disposal wells are likely to be part of the long-term solution. The Washington Post noted the lack of above-ground options for fracking wastewater disposal in 2015: “Currently there is no way to treat, store, and release the billions of gallons of wastewater at the surface.”

As Scanlon told DeSmog via email, “I think subsurface injection will continue to be an important part of the portfolio [of fracking wastewater disposal].” What remains to be seen is if that subsurface injection of fracking waste ends up mixing with the subsurface fresh water we rely on for survival.

Main image: A flare glows in the background on an Oklahoma unconventional well pad. Credit: Public Herald, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Here’s a question for you: having trained itself to use injection technology to solve the problem, when the current levels have reached capacity, do you think the industry is more likely to (a) find a new technique that will work as well for make go bye-bye, or (b) double down on what they got with an extra dose of ‘innovation’ (including higher pressures) and keep cashing in short-term?

Injecting the brine back into the petroleum reservoir is the old technology, and it works as both recovery enhancement and waste disposal in a conventional (non-shale) play.

Fracking is part a. but they are doing b. for waste.

I wondered about that; why don’t they just re-use the waste water in fracking? It uses huge amounts of water, mixed with noxious chemicals, which then comes back up, mixed with even more noxious chemicals. There’s a step in the logic missing here.

Part of the fracking process is dissolving the salts in the rock to create voids that allow the oil/gas to move. To do that, fresh water is essential. Salt water would not only be incapable of dissolving more salt, it could actually precipitate salt somewhere down there where it wasn’t previously present.

In conventional oil recovery, the waste water is injected back into the reservoir to force more oil out. That’s why this is a problem exacerbated by fracking.

Thank you; I was very puzzled about that.

This issue of fracking and earthquakes is getting bad everywhere. In the UK the shale gas firm Cuadrilla restarted fracking in the outer suburbs of the city of Blackpool back in October and they experienced five earthquakes within the very first days (https://www.ecowatch.com/earthquakes-reported-near-contentious-uk-fracking-site-2614332320.html) and you wonder if this is a portend of more serious earthquakes to come.

Not to worry as the UK Government is on the case. They have suggested raising the levels at which operations have to be suspended if there are any earthquakes felt-

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/09/uk-fracking-rules-on-earthquakes-could-be-relaxed-says-minister

Injecting fluid into rock creates earthquakes. That is essentially all fracking is.

The amount of energy released is IIRC related to how much fluid is injected, under what pressure that fluid is injected, the local geology, and the amount of strain accumulated in the rocks.

Some areas will see a few little quakes, others will see many quakes including relatively large events (M-5ish).

All rocks are under large tidal stress, our moon does that for us.

Earthquakes in Britain will have serious side effects, due to the prominent building method, unreinforced brick walls.

Not really. Tidal stress accumulates at high tide and dissipates at low tide. Its also millimeter scale. Tectonic stresses are kilometer scale.

In my state, my genius Ohioan state rep, the Republican Anthony DeVitis, has legislation that would allow the state to use fracking fluid as a de-icer on state roads due to its high salt content . This of course would not only find a solution for the fracking industry to get rid of its waste, it would create a whole new business to compete with the salt companies that sell salt to cities.

Supposedly, these fluids would be cleaned of any hazards such as radioactive material, which is often in the liquids, along with heavy metals and other disastrous and harmful stuff.

The profiteers can always find a lackey to do their bidding, and this piece of legislation shows just how far profiteers will go, regardless of what happens to the environment and its affects on ground water, animal life, human beings or just plain good sense. I really am beginning to hate these people, though as one attempting to practice the buddha-dhamma I try my best to be a person who does not operate on that harmful emotion.

That would be an interesting technology. I don’t believe it exists, Reverse Osmosis is not applicable.

Ha ha, too late:

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.newsweek.com/oil-and-gas-wastewater-used-de-ice-roads-new-york-and-pennsylvania-little-310684%3famp=1

http://www.post-gazette.com/business/powersource/2018/06/14/PSU-study-pans-roadway-brine-drilling-wastewater/stories/201806130183 https://www.desmogblog.com/2018/11/20/american-petroleum-institute-1965-speech-climate-change-oil-gas

https://www.propublica.org/article/wastewater-from-gas-drilling-boom-may-threaten-monongahela-river

Once CA’s aging reactors get bailed-out as carbon neutral…

https://www.commondreams.org/newswire/2018/11/20/beyond-nuclear-opposes-second-license-extension-peach-bottom-nuclear-plant?amp

Thanks for this article.

In this comment section, I’ve been in a lonely place saying (for years!) that fracking can and should be regulated based on what comes out, not what is put in. This article makes that case.

Brine and petroleum- contaminated water is what comes out of every fracked well as waste. If the oil-gas producers of the nation (world) can successfully treat this wastewater to drinking water standards and dispose of salts and sludges in a way that has minimal impact on the environment, then frack away. If not, no fracking.

But what about the earthquakes?

That IS waste disposal.

To be clear, I don’t think they can treat the waste. But if they did, then injecting is not necessary and the injection related earthquakes stop.

FWIW I’m a licensed geologist in several states. Beware! Texas is attempting to eliminate their geology licensing regulations.

Good article. The lack of shrillness in the tone is refreshing.

Small point: Enhanced oil recovery is a general term for techniques that help increase the amount of oil recovered. Injecting produced water into the reservoir during conventional drilling is only one of them.

The term ‘fracking’ is shorthand for the process known as ‘hydraulic fracturing.’ Hydraulic involves the uses of water, by definition.

So, earthquakes are bad. But, using 5 million gallons of fresh water, laced with sand and an unknown (trade secret) cocktail of chemicals, to blast rock, thus releasing oil and gas embedded in the rock, is, in the long term, even worse.

That is, for each well drilled, 5 to 9 million gallons of drinkable water gone for good. Or for a couple of millennia. Companies have recycled the used water to drill other wells, but, I suspect, it is cheaper to find sources of fresh water to use.

Using millions of gallons of fresh water per drilled well, in a semi-arid area such as Colorado’s Weld County, is a major concern to local opponents of fracking.

Eclair:

Focusing on what goes in, discounting what comes out. As the article explains, fracking waste stream is more dangerous than what gets put in during fracking, even considering 0.5 to 5 million gallons of freshwater per frack.

The trade secret stuff has been the focus of just about every green-loving person out there, when the entire operation can be demonstrated as an environments hazard through wastewater. They could frack using water, sand, ricin, uranium, and ebola virus and it wouldn’t matter since the brine and petroleum coming out would be hazardous enough by itself to shut down the operation.

The wastewater, and disposal of wastewater, is the way to end or regulate fracking.

If the well drillers have the water rights (in the states that have “western” water laws), there isn’t anything that can be done to stop them from using that water (given the current politics, R or D), no matter how wasteful or what impact that use will have. So while this is a critical point, it can’t be used to stop fracking. Wastewater (including the injection related quakes) is the key to eliminating and/or regulating oil/gas extraction, especially fracking.

Eclair, redleg,

Go to FracFocus to find out what chemicals have been used in a particular well.

Drilling companies have no rights to water; they usually buy supplies from the owners of water rights. That’s a private commercial transaction and it can mean a lot of money for the water seller. A drilling company would point this out in response to objections to fracking. Trying to convince owners of water rights in the West that they shouldn’t sell water to drilling and fracking companies is a painful endeavor.

I watched the 2010 documentary “Gasland” a couple weeks ago; I had to turn it off about 30 minutes in, because it was so depressing. Finished it a couple nights later.

Recommended.

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0fAsFQsFAs

A new book out by Bethany McLean (Enron reporting fame) makes the case that not a single fracked well is profitable. Fracking is a financial house of cards.