Jerri-Lynn here: This post examines US data and finds that the majority of kidney exchanges continue to be performed within hospitals – a fragmented market that imposes a large efficiency cost.

I wonder whether the authors are missing some details about why this is the case. These might include doctors not trusting the transportation arrangements for inter-hospital exchanges, particularly who is legally responsible for the organ during transportation and handoff, and thus prefer to conduct the entire operation in house.

Additionally, the parties involved might prefer completing transplants all under one roof, as such an arrangement would allow donors to see the patients who benefit from the exchange (perhaps?), or to be able to thank various parties and participants in the transfer chains.

Readers? Any thoughts? This is an area I know very little about but hope to foster discussion by posting this piece.

By Nikhil Agarwal, Itai Ashlagi, Eduardo Azevedo, Clayton Featherstone, Omer Karaduman. Originally published at VoxEU

National kidney exchange platforms significantly boost the number of life-saving kidney transplants by finding complicated exchange arrangements that are not possible within any single hospital. This column examines US data and finds that the majority of kidney exchanges continue to be performed within hospitals, suggesting a fragmented market that comes at a large efficiency cost. National platforms may need to be redesigned to encourage full participation, with reimbursement reform.

A transplant is a life-saving treatment for patients with kidney failure. Unfortunately, most patients will never receive a transplant because there is a severe shortage of kidneys. The waiting list for deceased donor kidneys now exceeds 100,000 patients. Some patients are lucky enough to receive donations from living donors: friends, relatives, and rare Good Samaritan donors (Matthews 2017).

But many patients who have a potential living donor cannot receive a transplant directly because they may not be biologically compatible. These incompatibilities occur because of blood type and because of the patient’s immune response to the donor’s proteins. Many patients with a willing donor remain unmatched because of biological compatibility.

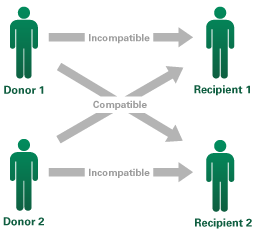

Kidney exchange is an innovative way to increase transplants. The idea is to find exchanges between pairs of patients and donors (Rothet al. 2004). For example, suppose Alice is willing to donate a kidneyto Benbut is incompatible; and Charlie and Debbie are in an identical position. However, it may be possible to transplant Alice’s kidney to Debbie and Charlie’s kidney to Ben (see Figure 1). Such a two-way swap enables both patients to receive a transplant, with each patient’s related donor only donating one of their kidneys.

Figure 1

Although Donor 1 is willing to donate a kidney to Recipient 1, and Donor 2 to Recipient 2, they are incompatible. However, it may be possible to transplant Donor 1’s kidney to Recipient 2, and Donor 2’s to Recipient 1.

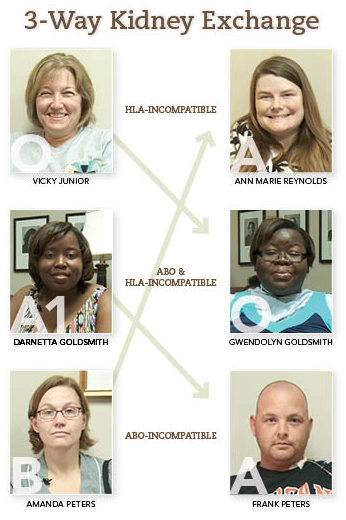

This basic principle has been extended to three-way swaps and even a six-way swap.1 Good Samaritan donors can also enable kidney chains, where each donates a kidney to a stranger, to transplant many more patients.2

Figure 2 A three-way exchange is also possible, extending the basic principle of the two-way exchange

Source: UAB News,The University of Alabama at Birmingham.

From 2008 to 2014, kidney exchange has grown from 300 transplants per year to 800 transplants per year. The system grew from one-off arrangements made by individual doctors or hospitals that were treating many patients, to a small consortia of hospitals, and finally to national kidney exchange platforms. These platforms use systematic computer algorithms that are able to find more complicated arrangements, such as kidney chains and three-way or four-way swaps. The algorithms are most powerful when a large number of patients and donors are all registered on the same system.

This evolution and growth of kidney exchanges have resulted from a mix of practical experimentation and academic studies. Medical doctors, economists, and researchers from various disciplines were involved with the creation of some of the first large kidney exchange platforms, and continue to work towards finding ways to better match patients and donors (Shute 2015, Roth et al. 2007, Rees et al. 2009, Anderson et al. 2015). By 2014, the national platforms were responsible for about 400 transplants per year.

The Impact of Market Fragmentation

In a recent study we found that, despite the growth of these national kidney exchange platforms, the majority of kidney exchanges continue to be performed within hospitals (Agarwalet al. 2018). Hospitals only sign up a fraction of their patients with national kidney exchange platforms, while many hospitals do not participate in any of the national platforms. And, even among most hospitals that do participate, kidney exchanges tend to be performed internally.

The evidence suggests that not only is the market fragmented, but this fragmentation has a large efficiency cost that reduces the total number of transplants performed. National platforms, because of their size, can find more transplant possibilities and therefore match a greater fraction of patients than any single hospital can.

-

- First, we found that hospitals conducting their own matches are more likely to perform inefficient matches. For example, models show that it is almost never optimal to transplant a blood-type-O donor to a patient that does not have blood type O in a kidney exchange. This is because a blood-type-O donor is universally blood-type compatible and his or her organ can usually be used to set up a larger cycle or chain. Yet, individual hospitals are two to four times more likely to perform this type of inefficient transplant than national platforms.

- Second, we used detailed data on transplants and knowledge of the matching algorithms to estimate how size influences the ability of a hospital or platform to perform kidney exchanges. We found that individual hospitals are too small to perform efficiently. According to our estimates, improving the matching via coordination through the large national platforms can increase the total number of kidney exchange transplants by 25-55%. This corresponds to a waste of 200-440 transplants per year.

Policy Implications

From a policy perspective, these findings suggest that we need to understand the reasons why hospitals do not participate more in national platforms, and design policies to increase participation.

There are two primary reasons why hospitals do not fully participate in kidney exchange platforms:

- First, current platform rules give incentives for hospitals to hoard easy-to-match patients and donors. Using these easy-to-match patients and donors in internal exchanges can often help the hospitals transplant other patients, while submitting them to a national platform may leave these patients un-transplanted. But registering the easy-to-match patients and donors brings a greater benefit to the kidney exchange system as a whole. Thus, current platform rules often put the hospitals in the difficult position of having to choose between helping their own patients or doing what is bestfor the system as a whole.

- Second, hospitals have to incur unreimbursed costs of participating in kidney exchange platforms. These include hiring additional transplant coordinators, performing additional medical tests, and paying platform fees. These costs are not covered by Medicare or insurance companies and can be a barrier to participating in kidney exchange platforms, particularly for small hospitals.

Both of these problems can be fixed using simple policies. Redesigning platforms with an eye towards encouraging full participation can alleviate the first problem. The platform can prioritize patients at hospitals that register altruistic donors as well as their easiest-to-match patients and donors, which could encourage hospitals to register those patients. These easy-to-match patients and donors are essential in arranging kidney exchanges. For example, altruistic donors are necessary for starting kidney chains that enable transplants for many patients. Hospitals should be encouraged to register altruistic donors at national platforms, which can set up long kidney chains.

Fixing the second barrier calls for reimbursement reform, both at the federal level and at the individual insurer level. This concern has been voiced by researchers and by the medical profession as well, who have proposed ways in which to alleviate this problem (Rees et al. 2012).

These lessons may be applied more broadly. Most European countries that have a national kidney exchange platform require full participation and do not face this free-riding problem (possibly due to the structure of the health system). However, each of these platforms is small and some countries, such as Austria and the Czech Republic, and Italy, Spain, and Portugal, have been trying to combine their platforms. Just like some hospitals do in the United States, these countries have so far shared only the patients and donors that they cannot match internally, leading to poor results. The results from this study can explain some of the challenges and potential solutions in this endeavour.

There are many other approaches currently being explored to expand kidney exchange, and make it a more effective tool so that patients currently waiting for a kidney can get a transplant. One idea, proposed by researchers at Boston College, is to find ways in which all kidney patients with living donors are incentivised to participate in kidney exchanges by utilizing the deceased donor pool (Sönmez et al. 2017). Another proposal is to use kidneys from deceased donors to initiate kidney chains (Haynes and Leishman 2017). These innovations hold the promise of vastly expanding the number of kidney transplants that may be possible.

References

Agarwal, N, I Ashlagi, E Azevedo, CR Featherstone, Ö Karaduman (2018), “Market failure in kidney exchange”, NBER Working Paper No. 24775.

Anderson, R, I Ashlagi, D Gamarnik and AE Roth (2015), “Finding long chains in kidney exchange using the travelingsalesman problem”, PNAS 112(3): 663-668.

CBS News (2018), “Patients of six-way kidney swap meet for the first time”, video, 20 January 2018.

Matthews, D (2017), “Why I gave my kidney to a stranger — and why you should consider doing it too”, Vox.com, 11 April.

Pope, A (2018), “Nation’s longest single-site kidney chain passes 100”, Alabama Newscenter, 19 August.

Rees, MA, JE Kopke, RP Pelletier, DL Segev, ME Rutter, AJ Fabrega, J Rogers, OG Pankewycz, J Hiller, AE Roth, T Sandholm, MU Ünver, et al. (2009), “A nonsimultaneous, extended, altruistic-donor chain”, New England Journal of Medicine 360:1096-1101.

Rees, MA, MA Schnitzler, EY Zavala, JA Cutler, AE Roth, FD Irwin, SW Crawford, AB Leichtman (2012), “Call to develop a standard acquisition charge model for kidney paired donation”, American Journal of Transplantation 12(6): 1392-7.

Roth, AE, T Sönmez and MU Ünver (2004), “Kidney exchange”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(2): 457–488.

Roth, AE, T Sönmez and MU Ünver (2007), “Efficient kidney exchange: Coincidence of wants in markets with compatibility-based preferences”, American Economic Review 97(3): 828-851.

Shute, N (2015), “How an economist helped patients find the right kidney donors”, NPR, 11 June 2015

Sönmez T, U Unver and MB Yenmez (2017), “Incentivized kidney exchange”, Boston College Working Papers in Economics 931 (revised 2018).

Haynes, CR, and R Leishman (2017), “Allowing deceased donor-initiated kidney paired donation (KPD) chains”, OPTN/UNOS Kidney Transplantation Committee, concept paper.

Endnotes

1 See https://www.cbsnews.com/video/patients-of-six-way-kidney-swap-meet-for-the-first-time/

2 See https://www.alabamanewscenter.com/2018/08/19/nations-longest-single-site-kidney-chain-reaches-100/

I fail to see how a human being can associate ‘market’ and ‘kidney exchange’ in a single sentence.

One can paraphrase Dani Rodrik and say ‘you can have two but not all three’.

Are you claiming that there is some sphere of human or natural interaction that is not best described and embodied as a market? You’d best keep those thoughtcrimes to yourself “Jeff”, or you’ll be whisked off to the TINA camps before you can intone the Thatcher Catechism* 3 times.

* “There is no such thing as society”

“The market in kidneys is illegal, so people have to use a half baked kidney exchange program, so many of them die.”. That said even the current half baked system is a big improvement vs the previous go find the most compatible donor who loves you enough to have major surgery for free system. I guess any dollar going to a donor is a dollar not going into the pocket of a doctor or hospital or insurance company, so it’s somewhat understandable that they would all of a sudden get religion about not mixing money and healthcare…

A market without money or other compensation to the provider? Everybody in this situation – hospital, doctor, academician, etc. – gets paid, except the donor ! If I may, the devil’s advocate asks: “why not pay donors?”. Giving up a kidney has an actuarially-calculable cost in lost years of life, upfront risks, greater exposure to disease, etc. Why not set up a regulated market, total transparency to guard against criminal abuse like the reputed Chinese habit of harvesting organs from executed prisoners, just for kidney donations? One hundred thousand people just in the USA waiting for kidneys – most will die without a transplant. And I would wager a large sum of money that with a justly high price, say $250,000, the donor pool would be over-subscribed.

How is this any different for a donor than working for thirty years in a dangerous job that takes 15 years off your life?

Now Jeff’s comment above takes the moral absolutist high ground – which rejects outright any donor compensation. Rather he says anyone advocating for donor comp is not human.

I’m interested in other ethical arguments. I think we are already well down the road to donor comp already with the US for-profit health system. Making excessive profits on sick people is the industry standard, no?

Hey, paying for kidneys works just great in Rural India and other places! https://qz.com/india/755854/top-indian-hospitals-are-buying-kidneys-from-poor-villagers-to-sell-to-rich-patients/ And people like Dick Less Cheney, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2012/03/28/cheneys-million-dollar-heart-stirs-health-care-debate-who-lives-and-who-dies/, will always find their way to the top of the queue. And then you have the Chinese ‘efficiency” solution: cut the organs out of executed prisoners. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1165416/Chinas-hi-tech-death-van-criminals-executed-organs-sold-black-market.html At least in the lede case, a corrupt official is the ‘donor.’ So he had his years of hedonic pleasure.

Another reason why people tend to hate “economists.”

From a retired nurse, with a little exposure to the wonderful world of markets in the medical setting, may I dare to say, “F@CK YOUR MARKET EFFICIENCY ‘SOLUTIONS.’”

I’ve looked, but there is no compendious and satisfactory answer I would accept to the complex question, “What is a human life worth?” Given all the manifold things that humans do with their lives, in relation to other humans. I’d value Cheney’s, Kissinger’s and other such “lives” at a very large negative number. But that’s just one vote.

Hey! Maybe we humans with our tech could have a referendum on transplants for notorious famous individuals! Thumbs up? Thumbs down?

Well thanks for participating. Next time, please read what I actually wrote rather than what you would like to think I wrote.

Anyway, as you raise India, this would be an example of an unregulated market. Not what I proposed.

However, your point that the rich (E.g. the odious Mr. Dick “Satan” Cheney) would get their kidneys not the saintly poor, well, yes a valid point that could be dealt with in a properly regulated system.

As to “what’s a human life worth” – actuaries calculate this every day. And as we have two kidneys, a kidney donor continues to live. SO – my question for you is – what’s the life of someone who will die without a donated kidney worth? Why not pay someone to donate a kidney for this person who would otherwise die?

And yes, the for profit health system in the USA is already morally and ethically dubious – Medicare for all is the ultimate solution which IMHO will happen when we can mitigate the rule by cartels we live under.

Thanks for the thoughtful response. It leads to other questions, some of which you pose yourself. First off, I believe that not all kidney donors live out the full lives that are presumed above. Insurance actuaries seem to feel that way: https://www.bestlifequote.com/blog/could-donating-a-kidney-put-life-insurance-at-risk/ That is aside from the risks of going into a hospital full of pathogens and fallible humans, and undergoing abdominal surgery.

But donating a kidney is indeed a worthy act.

You answer your own response on what the life of a person who will die (presuming dialysis does not keep them going, or some other medical miracle comes along) without a transplanted kidney — “Actuaries,” our source of morality and eithcs apparently, “calculate this every day.” As a former attorney I might offer that kin wrongful death and other tort actions, lawyers for each side come up with “actuaries” with the acceptable credentials to qualify as “expert witnesses” and said actuaries come up with vastly divergent “values” for human life in very specific situations.

I had in mind a much bigger question, given all that is transpiring in the world today. What is the life of a Yemini peasant, or CIA or special ops wet worker, or even immediate past or present president, worth, in the larger value system of the world? Looks to me like the calculus that integrates all the stuff that “we” are doing, to ourselves and others across the planet, comes up with some kind of imaginary number that would appear to have a negative value.

What kind of political economy do “we the people,” taken as a whole, want to live (and die, horribly or comfortably) in?

Your case that people suck, so we should put the dollars that can save their lives to better use is actually kind of convincing. I guess we do an actuarial calculation of a person’s expected future contribution, then decide whether to send them to the hospital or to a place where judgy nurses insult them as they die so people can feel better about leaving the world. Then spend the money that would have gone to the hospital on climate change or something. “Remember Iraq, bitch! The living will envy the dead in the garbage world you created! Death will be a sweet mercy!”

That’s appealing, but I bet Cheney would just pull some strings like he does in the real world, so we might as well just set up a system that helps sick people IMO.

First time poster, long time lurker, and only really posting since I’m actually on the transplant list. Our society has enough parts of it that are obsessed with “market-based solutions.” Really don’t think we need to have organ donation as one of them.

Agreed – the word ‘market’ used anywhere remotely in connection with organ donation gives me the heebie jeebies.

I think the use of the term devalues the article, which is not really about markets at all but donor exchange platforms. Perhaps it’s being used based on duck typing of the platform concept, but the resemblance is only superficial. I’d prefer that we avoid the term unless we are (God forbid) actually suggesting unleashing neoliberal approaches on the organ transplant market.

I thought markets were famously inefficient, but effective.

Re: The Palace and the Storm.

Why bother to read a story that starts out …a single house stands unscathed… when in the picture there are several houses that appear to be just that?

The root of the problem is the people in need of a kidney, or any other organ, outnumber the supply available. Kidney exchange is feasible since living donors are involved unlike say a heart or liver. The less the ‘market’ is involved in healthcare the better. As others have said the market is not efficient. Financial incentives by hospitals are a problem. Some countries have an automatic donor registration system with an ‘opt-out’ feature. That would increase the potential organ supply. Probably would be impossible to implement in the U.S. due to religious objections.

I did not understand while reading this: why aren’t we just as a society going full bore on signing up organ donors? Like the kind of campaigns we had to reduce drinking and driving or stop smoking?

Someone living life with only one kidney is taking a terrible risk. We are mutilating people when we could be getting organs free from cadavers.

That donated organs come from cadavers is kind of a misconception. They generally come from people that are soon to be cadavers, and are on ICUs in hospitals. Usually from a car wreck. Organs start rapidly deteriorating as soon as a person dies, so you can’t just take an organ from a corpse. Organ donations from living donors are significantly more effective than those from “deceased” donors even so.