By Arthur Dyevre, Professor of Empirical Jurisprudence, Monika Glavina, PhD student in Law, Nicolas Lampach, Postdoctoral researcher, Michal Ovádek, PhD student, and Wessel Wijtvliet, Researcher, all of KU Leuven. Originally published at VoxEU

Twenty-eight months after the Brexit referendum, EU laws, regulations, and doctrines continue to apply to UK residents and state officials. This column shows that UK judges and litigants have already started to move away from EU law in anticipation of Brexit, with judges submitting 22–23% fewer questions to the European Court of Justice since the referendum. The broader lesson for the future of supranational legal systems is that effective disintegration may precede formal withdrawal, or may occur even if formal withdrawal is delayed or does not come about.

The impact of the Brexit vote on the British economy has already received a fair share of attention in the economic literature, with studies examining the effect of the referendum on stock prices (Breinlich et al. 2018, Davies and Studnicka 2018), GDP growth (Born et al. 2018), bond yields (Chadha et al. 2018), and UK exports (Crowley et al. 2018). The uncertainty generated by the referendum, though, has implications that go beyond trade flows, stock market fluctuations, and investment decisions and extend to the UK’s political, social, and legal institutions.

In a recent paper, we investigate the effect of Brexit uncertainty on the legal institutions that underpin the application of EU law in the UK, which allow UK courts to pass on cases to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) (Dyevre et al. 2018). We find that UK judges submit 23–30% fewer references to the ECJ after the Brexit referendum, compared to a counterfactual scenario.

The Preliminary Reference Procedure and Uncertainty

The preliminary reference mechanism, which is legally enshrined in Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, is a foundational feature of EU law enforcement. It allows judges to refer questions concerning interpretation of EU law to the ECJ. The ECJ then rules on the case – taking on average 18 months – after which the referring court is mandated to implement the ECJ ruling in the domestic case. Importantly, litigants do not have the right to have a question referred to the ECJ. The operations of the EU legal order thus rest on a decentralised system in which national courts act as gatekeepers and compliance partners of the ECJ. Unlike in hierarchical, centralised judiciaries, the ECJ cannot step in to restore compliance by reversing the decisions of reticent national courts. This makes the EU legal order highly vulnerable to uncertainty.

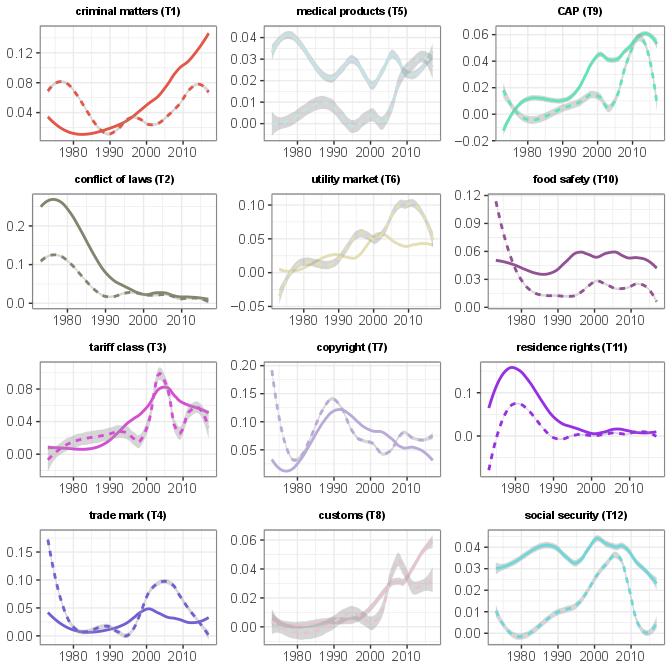

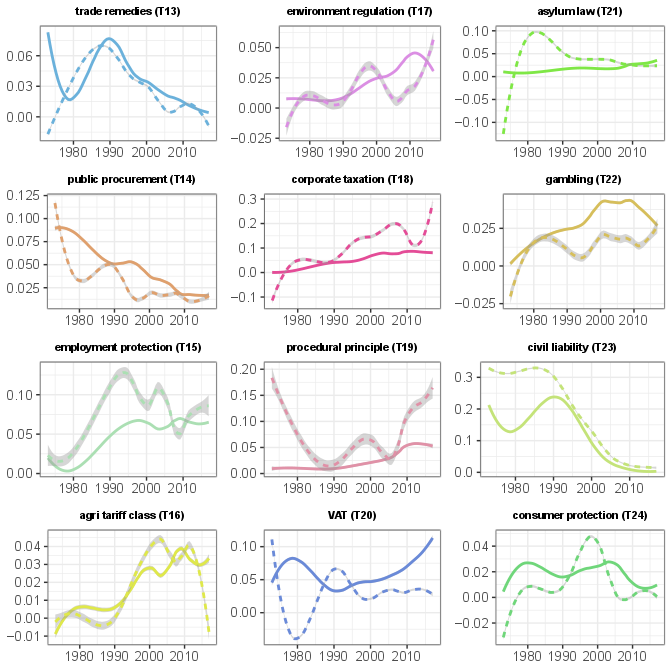

Preliminary references have always been at the heart of EU law, permitting the ECJ to develop legal doctrines and assert its role in EU integration. Domestic courts have also been submitting references at increasing rates, referring more than 9,000 cases between 1961 and 2017. As shown by the topic model in Figure 1, most cases pertain to core EU policies such as the common agricultural policy, tariffs, VAT rules, and various aspects of the internal market.

Figure 1 Dynamic topic model of cases referred to the ECJ by national courts between 1973 and 2017

Note: Dashed line indicates topic proportion for UK courts. Solid line shows topic prevalence for the courts of the other EU member states.

The Brexit referendum and the inability to quickly settle the terms of exit have created considerable uncertainty, which puts UK judges and litigants in a delicate situation. Why submit a reference to the ECJ if, by the time it is announced, the preliminary ruling might have no legal authority? Moreover, litigation and litigants’ argumentation strategy being endogenous to judicial decision making, litigants will adapt their choice of arguments to what they believe the judges are likely to accept. As a result, knowing that it will be harder to convince a UK judge to request a preliminary ruling, litigants may choose to prioritise domestic law arguments over EU law arguments. Such a flight-to-domestic law may precipitate the unravelling of legal integration even if Brexit, in the end, does not materialise.

Comparing a World with Brexit to a World Without

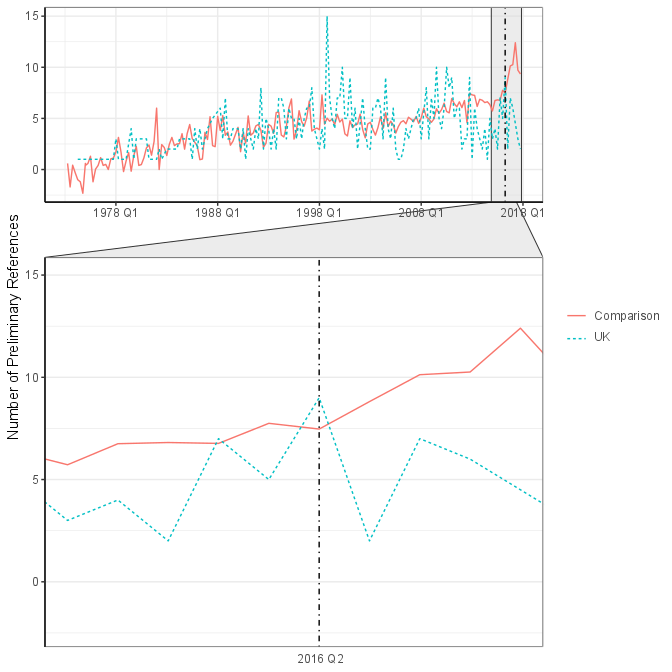

We may be tempted to assess the effect of Brexit by simply comparing the referral rates of UK courts before the referendum to their referral rates post-referendum. If we do this and look at quarterly referral counts (how many Article 267 references are submitted by British courts every quarter), we do, indeed, find post-referendum referral rates that appear low. In the second quarter of 2016 (April–June), UK courts submitted nine references, but only three in the third quarter immediately following the referendum. However, it is difficult to attribute this to a Brexit-effect for several reasons. First, relative to the size of the UK’s population, referral rates for British courts have traditionally been below the EU average. Second, referral rates exhibit strong quarter-to-quarter fluctuations. Typically, judicial activity tends to be lower in the third quarter of any year, as it coincides with the judicial holiday. Finally, there are all the confounding factors that can affect referral propensity, such as lower intra-EU trade (EU law is largely about trade in goods), lower public support for the EU (judges who don’t like the EU also don’t like the ECJ), variations in migration patterns (if fewer people cross borders, there are fewer instances where EU law can be invoked), and so on.

To measure the effect of Brexit on British courts, we compare the real-world UK to what the UK would look like had the referendum not taken place. To do so, we construct a synthetic UK from the other bits of the EU that look like the UK, and then compared the real-world UK to this counterfactual. We follow a more data-driven approach, relying on machine learning methods to choose the country attributes associated with referral activity before the Brexit vote and assign weights to countries resembling the UK. This combination of learning models with a weighting strategy has emerged as a powerful alternative to matching algorithms (Stuart et al. 2010, Lee et al. 2010, Westreich et al. 2010). Our learning algorithm assigns high weights to Ireland, France, Germany, and Denmark.

Figure 2 shows that our synthetic UK (solid line) predicts referral rates that are (minus random fluctuations) very close to the real-world UK (dashed line) until the referendum. After that, they diverge. UK judges are referring 22–23% fewer references after the vote than the judges in our synthetic UK. The effect is even larger and reaches 30% when we count the first two quarters of 2018 (this requires dropping some covariates for which data is missing, though). The effect is even larger and reaches 30% when we count the first two quarters of 2018 (though this requires dropping some covariates for which data is missing). Our results are robust to using matching-algorithms or an alternative weighting strategy, showing a small increase in the effect size. Overall, we find strong evidence that the referendum has adversely affected the use of EU law.

Figure 2 Effect of the Brexit vote on EU law application by British judges

The future relationship between the EU and the UK is still in limbo. But our study suggests that the uncertainty created by the political process has already begun to unravel the fabric of the legal institutions that made European integration possible. The broader lesson for the future of supranational legal systems is that effective disintegration may precede formal withdrawal or may occur even if formal withdrawal is delayed or, for some reason, does not come about.

Authors’ note: The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from European Research Council Grant 638154 (EUTHORITY).

See original post for references

Given that Judicial procedures take some time this is not surprising.

I think UK Common Law’s arbitrariness and wide (excessive) latitude offered to judges, compared to continental (Roman) Civil Law, is responsible for this effect.

It would be interesting to compare the decisions of Scottish judges, as Scottish law is more influenced by Civil Law than English law.

There may be an even greater divide coming up between Common Law and the EU as I’ve been told its been openly discussed in Brussels that the remaining Common Law jurisdictions, Ireland and Malta, will be encouraged to move to a more Civil Law system to allow for more cohesion in European law.

Yes. But at the same time, there’s a problem. IIRC, the capital instruments for EU institutions must be under the EU law. A lot of them were issued under English law. Fine, the EU gets an exception for those, but requires all the new ones to be issued under an EU law.

But it’s actually problem for investors. Because they are used to the English law here. It has decades of rulings, precedents etc. for just about anything you run into. And it’s in English. So most of them can read it themselves, and not a second-hand version of a some lawyer working in a law you can’t read or understand, and that may have no previous ruling on it etc.

Great fun for lawyers, but may mean less uptake of the instruments by international investors.

I agree. There’s a detailed and very thoughtful examination of the differences, similarities and — crucially — implications given by a UKSC justice here https://www.supremecourt.uk/docs/speech-141111.pdf

For as long as I can remember (20 years or more), many counties — not just European ones — have due to various economic and political wish-listing wanted to “take business away from London” and New York. They’ve not made exactly stellar progress. Of course, times change and This Time May Really Be Different. And yet, the countries concerned are loathed to do the nitty gritty compromises and trade-offs which that will demand.

It’s no use, for example, harrumph’ing about US thumbscrews being applied to Iranian sanctions (executed by the means of denying access to SWIFT, a current bete noir of EU countries) when the countries concerned won’t run limitless trade deficits to create a sufficiently large pool of non-US$ liquidity nor will they be demonstrably willing to backstop money centre banks. And they certainly don’t seem willing to resist the occasional temptation to treat their courts as biddable pets which can be nudged into favouring certain parties more than others, nor change legal systems in such a way which would allow the flexibility needed to support redress for disputes in the contracts being drawn up by those wishing to enter into complex instruments.

I didn’t mention the NY law, as that’s not applicable for the EU capital instruments right now anyways, but clearly is in the same boat.

With this, two most widely used laws for the issuance of instruments to investors get marginalised by the EU.

Let’s see how well that works.

https://www.npr.org/2018/11/22/670303536/britain-and-eu-have-drafted-a-comprehensive-post-brexit-agreement

Haven’t read it.

There seems to be quite a lot going on behind the scenes.