Yves here. As you’ll see, the authors below find that industrial policy produces net benefits even after retaliation, which on average lowers the revenue gain benefit to the companies receiving the industrial policy support by 25%. The authors seem to shade this finding in the direction of emphasizing that the cost of achieving an expected level of export benefit are lower than naive calculations might assume. But given how allergic the US and neoliberal infested Eurospehere are to explicit industrial policy (as opposed to by default, as in as a result of powerful interest groups lobbying for bennies), this finding counters the belief in a hands-off approach. And as many have pointed out, including yours truly, the history of Trump 1.0 confirms the idea that tariffs alone, without other supporting policies, will not be sufficient to generate much return of manufacture to the US.

However, there is at least one reason for caution in applying this finding to the US and Europe. As is becoming more and more widely recognized, what passes for leadership in these countries can’t manage its way out of a paper bag. So it is an open question as to whether these countries could design and implement effective industrial policies.

By Yusheng Feng, Haishi “Harry” Li, Assistant Professor of Economics University of Hong Kong, Siwei Wang, PhD candidate Wuhan University, and Min Zhu. Originally published at VoxEU

Industrial policy is increasingly implemented worldwide, with many policymakers and researchers highlighting its benefits. However, the cost of industrial policy remains less understood. Using Chinese firm-level data, this column shows that higher industrial subsidies raise the likelihood and severity of foreign anti-dumping and countervailing duties at each investigation stage. These retaliatory tariffs wipe out roughly a quarter of the firm revenue growth the subsidies would otherwise create. Neglecting this channel may lead governments to overstate the net benefits of industrial policy and fuels deeper trade frictions and geoeconomic fragmentation.

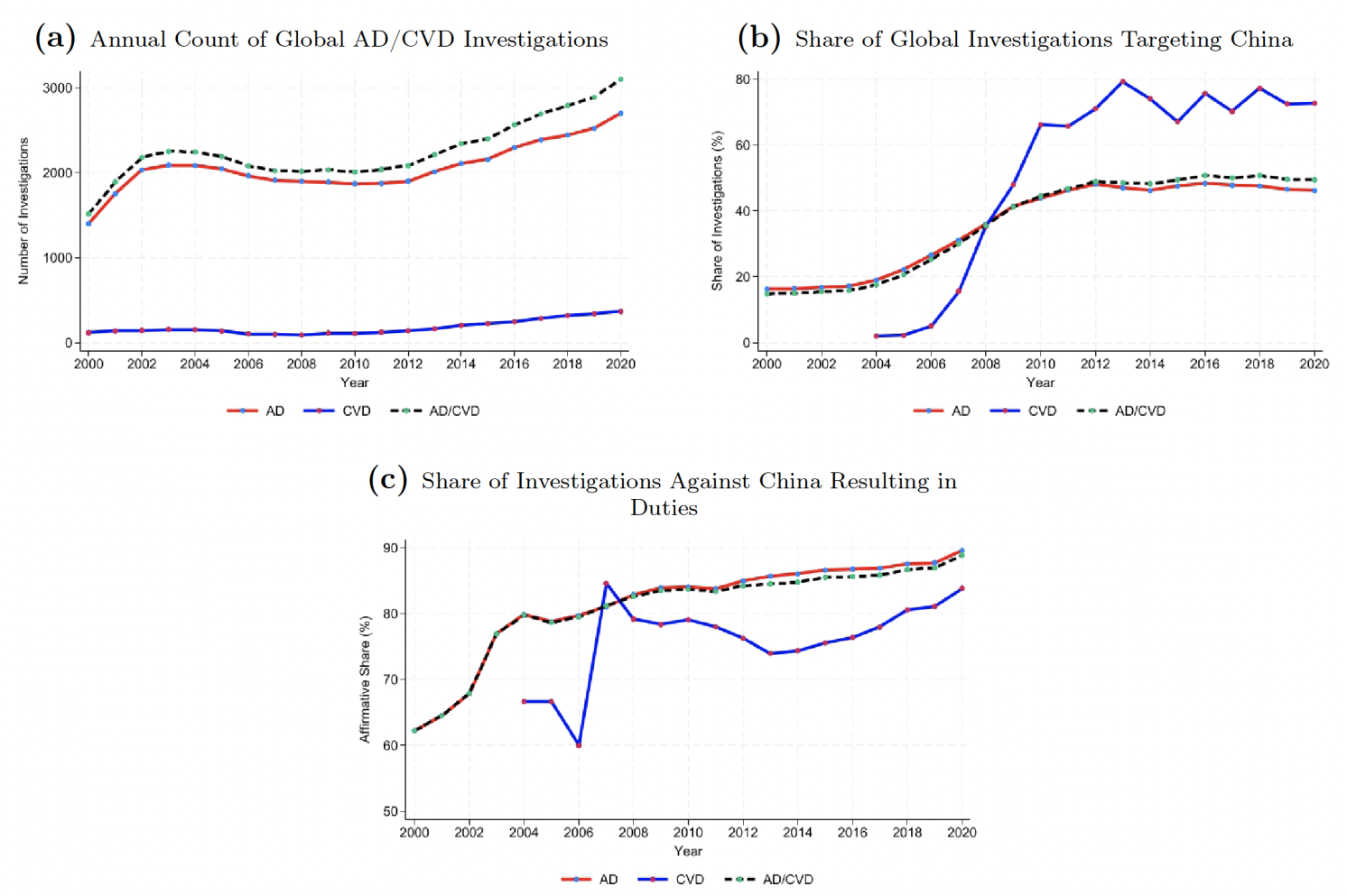

Over the past two decades, China has become the primary target of antidumping and countervailing (AD/CVD) investigations globally, accounting for roughly one-third of all cases, as Figure 1 illustrates. Both the frequency of investigations and the share resulting in duties have increased significantly. By 2020, around 15% of Chinese exports to the US were subject to AD/CVD tariffs.

Figure 1 Trends in global AD/CVD investigations and China’s exposure

Notes: Figure 1 illustrates trends in global AD/CVD investigations from 2000 to 2020. Panel (a) reports the annual count of investigations worldwide. Panel (b) displays the share of these investigations that targeted China. Panel (c) presents the share of investigations against China that resulted in affirmative outcomes (i.e., the imposition of duties).

Source: Temporary Trade Barriers Database (Signoret et al. 2020) and authors’ calculations.

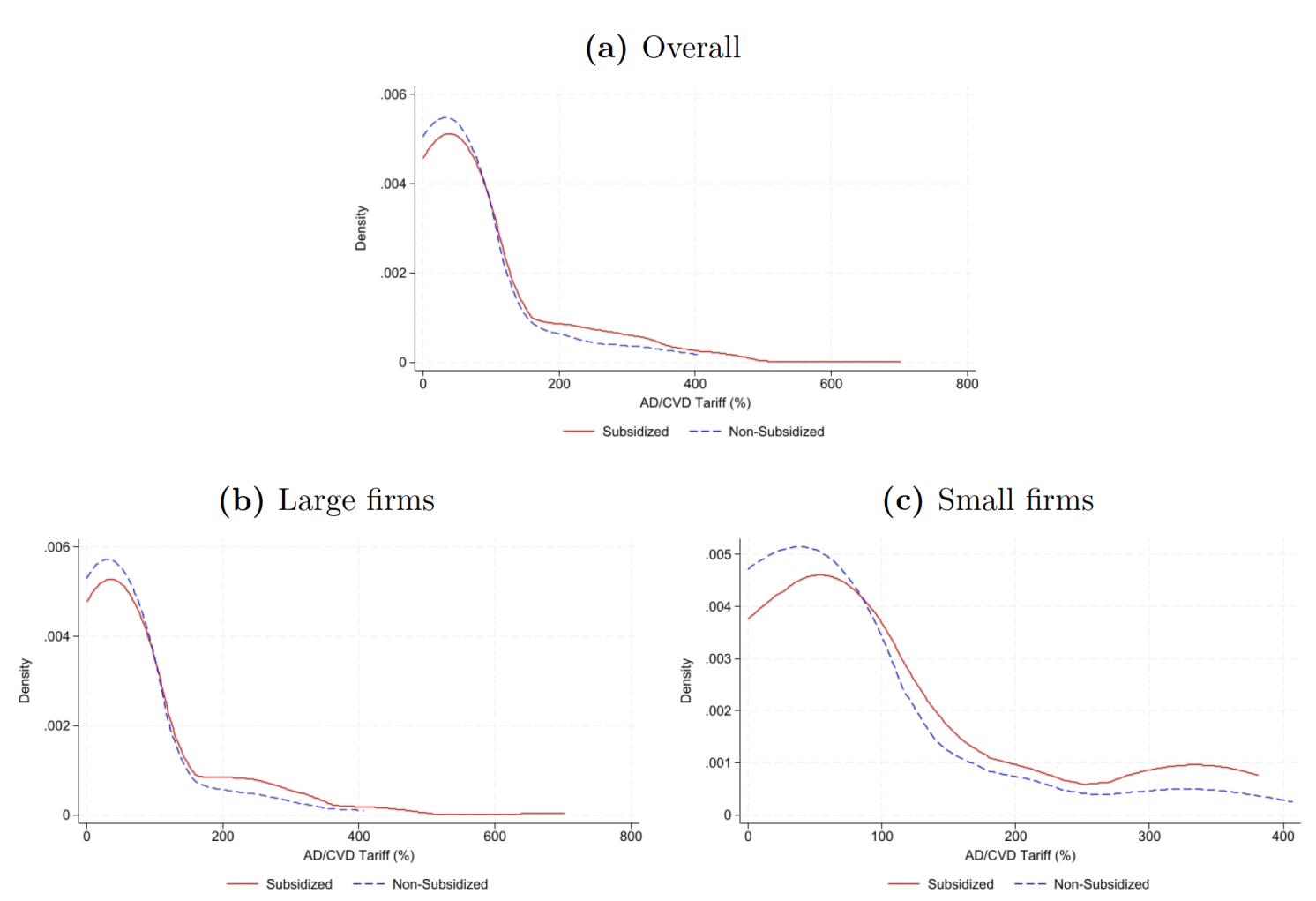

Moreover, subsidised firms are disproportionately affected. Figure 2 shows that the distribution of tariffs for subsidised Chinese exporters is significantly right-shifted compared to non-subsidised Chinese exporters, indicating consistently higher duties. This pattern is robust for both large and small firms.

Figure 2 AD/CVD duty distribution for subsidised and non-subsidised Chinese exporters

Notes: This figure compares the distribution of AD/CVD duty rates between subsidised and non-subsidised Chinese exporters. Panel (2a) presents the overall distribution, where the red solid line represents subsidized Chinese exporters and the blue dashed line represents non-subsidized Chinese exporters. Panels (2b) and (2c) show the distributions separately for large Chinese exporters (above-median assets) and small Chinese exporters (below-median assets), respectively. Firm size is measured using the log of total assets.

Motivated by these facts, in a recent paper (Feng et al. 2025) we examine the impact of Chinese subsidies on foreign AD/CVD investigations by combining comprehensive data on Chinese industrial firms with the global universe of AD/CVD cases against China. We find that higher industrial subsidies lead to more adverse AD/CVD measures at all stages of AD/CVD investigation. Specifically, heavily subsidised products are more likely to receive affirmative AD/CVD rulings, which lead to tariffs. Among affirmative investigations, industrial subsidies also lead to higher tariffs. At the firm level, firms receiving larger subsidies are less likely to be granted firm-specific duties, which are lower than product-level tariffs applied to other exporters of the investigated product. Among those that do receive firm-specific treatment, higher subsidies are associated with higher assigned duty rates.

Retaliatory tariffs offset approximately 25% of the subsidy’s positive impact on firm growth. Researchers estimating the effect of industrial policies should account for the associated increase in AD/CVD duties. Ignoring this subsidy cost creates a downward omitted variable bias because the resulting duties undermine firm growth.

AD/CVD Duties Become a Significant Subsidy cCost for Heavily Subsidised Firms or Those sSeeking Firm-Specific Rates

We find that a one percentage point increase in a firm’s subsidy rate leads to a 0.16 percentage point rise in the expected AD/CVD tariff for an average firm in the economy (see Table 5 in our paper). Despite this moderate average effect, the highly skewed distribution of subsidy rates means firms in the right tail face significant trade cost. A firm increasing its subsidy rate from the 5th percentile (0%) to the 99th percentile (115%) expects to face an 18 percentage point increase in foreign AD/CVD tariffs.

Moreover, among firms that appeal for firm-specific tariffs, as their subsidy information undergoes scrutiny during the investigation, the tariff increase is substantially larger. We find that a one percentage point increase in the subsidy rate leads to a 2 percentage point increase in the assigned AD/CVD tariff (see Table 4 in our paper). At the same time, the probability of receiving the firm-specific rate falls by 0.7 percentage points (see Table 3 in our paper). Given that the average product-level tariff is 145% while the average firm-specific tariff is 81%, this translates into a 47 percentage point increase in the expected tariff faced by firms potentially eligible for firm-specific treatment.

Tariffs Significantly Erode the Benefits of Subsidies

The intended benefits of industrial subsidies on firm revenue growth, employment and productivity are partially offset by increased foreign trade protection. Using an instrumental variable strategy, we compare five-year revenue growth across firms with different subsidy levels, both with and without controlling for AD/CVD tariffs. We find that when tariffs are omitted, a 1 percentage point increase in the subsidy rate leads to a 1.2% increase in revenue (see Table 10 in our paper). When tariffs are included, the same subsidy yields a 1.5% gain. The 0.3 percentage point difference implies that retaliation offsets approximately 25% of the subsidy’s growth effect. Similar attenuation is observed in firm-level employment (17%) and productivity (30%).

Conclusion

Researchers have shown the widespread use of industrial policies in countries such as China (Barwick et al. 2024) and their resulting trade spillovers into other economies (Rotunno and Ruta 2024). While many policymakers and researchers have highlighted the benefits of industrial policy, (Juhász et al. 2023), our findings reveal a hidden cost: under WTO rules, subsidies lead to more adverse outcomes at every stage of AD/CVD investigations. This mechanism helps explain the recent parallel rise of industrial subsidies and trade protection. The resulting tariffs offset about 25% of the subsidies’ positive effect on firm revenue growth. Policymakers aiming to promote exports should consider how subsidy design shapes trade responses – targeting sectors that impose less foreign harm or relying on alternative, non-subsidy tools that are less likely to trigger retaliation.

See original post for references

“The authors seem to shade this finding in the direction of emphasizing that the cost of achieving an expected level of export benefit that naive calculations might assume.”

Isn’t this sentence missing a part?

Aargh, I keep doing this, revising a sentence on the fly and then not double checking what I did. Fixing.

If I’m not misunderstanding this paper it isn’t really about industrial policy – its specifically about industrial subsidies (just one small element of industrial policy). Its unsurprising to find that there are benefits for growing economies – Japan, Taiwan and ROK all pursued successful policies of providing hidden and not so hidden subsidies for industries in their initial growth stages. Many European countries have done it to various degrees over the years (and continue to do so at an EU level), and Indonesia is going all in on this for their steel industry. It clearly works, despite what conventional economic theory tells us. You could certainly argue that it is the only way to develop an industrial sector when you are facing established incumbents.

I’m a bit sceptical though about using China as an example, because subsidies within China tend to be allocated on a regional basis and are as much about inter-regional competition within China as it is about seeking export success.

So it is an open question as to whether these countries could design and implement effective industrial policies.

No, it’s not. Western political “leadership” is stuffed and beyond redemption.

If I were a reviewer of this paper, I would send it back (with major revisions) for not writing a discussion section on the transferability of their findings to countries other than China. It is hard to imagine the same results for similar policies in Uruguay against the US (and Western) retaliation, with tools including military invasion, funding internal civil wars, corruption of leaders, etc., which are infeasible in China.

But even if we ignore non-economic retaliation, the authors assert their findings’ universality* without supporting arguments.

* They argue that “policymakers” should consider their findings, not “Chinese policymakers.”

Michael Hudson is right. You can’t jack up health care, housing, and education costs to the stratosphere and expect that buying a big chunk of Intel will somehow solve the problem.