Yves here. Since the economists mentioned below got in quite a fistfight, I’ll only add one observation: the notion that higher taxes mean entrepreneurs would leave is nonsense. Starting a new business requires above all customers. A foreign transplant won’t have them and will be disadvantaged in acquiring them. And that’s before these pundits having no clue as to how hard an international move is when you don’t have an employer sponsoring it. Already rich people may give up their citizenship, but that’s a different category.

By Enrico Bergamini, Research Assistant at Bruegel, and previously a data science consultant for the NGO Action Aid. Originally published at Bruegel

During a panel at Davos, Dell founder Michael Dell was asked about his opinion on the proposal of a 70% top marginal tax rate; he replied: “Name a country where that has worked. Ever.”

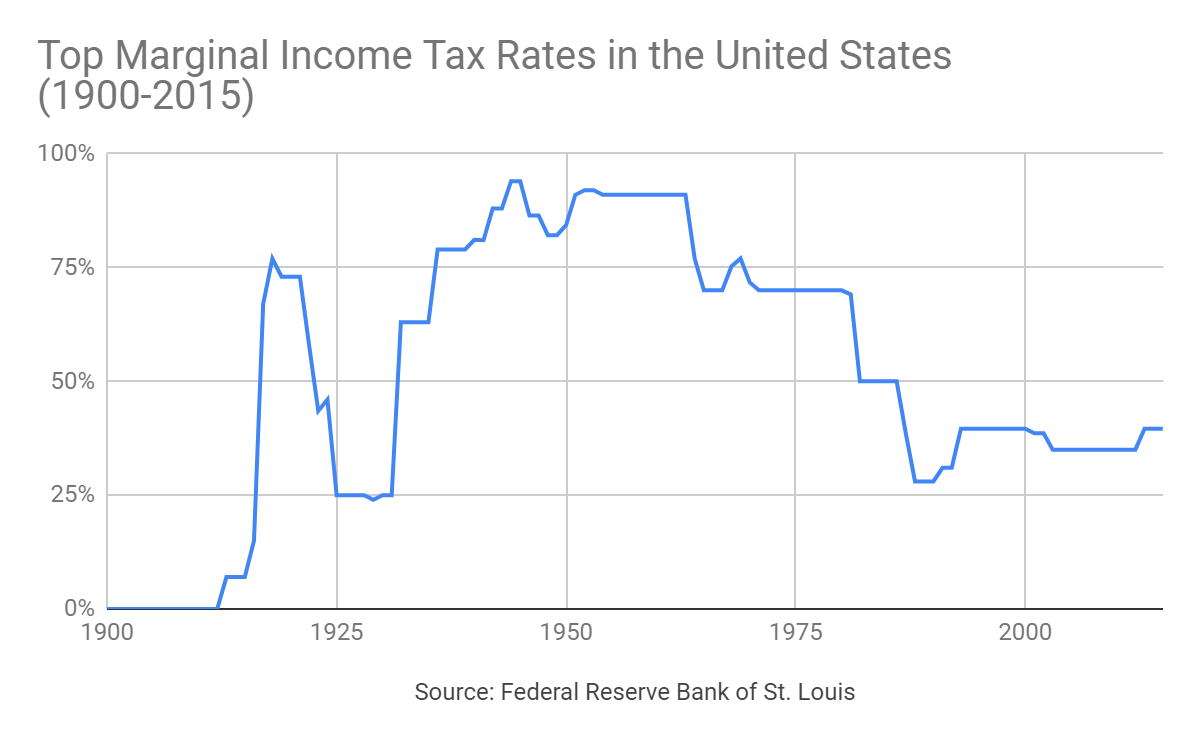

Co-panelist Erik Brynjolfsson (MIT) names the United States, in between the 1930s and the 1960s, when the average top rate was higher than 70%, with peaks of 91%.

On January 4th, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – newly elected Congresswoman and rising star of the Democratic Party – proposed in an interview with 60 Minutes to raise the tax rate to 70% on incomes above $10 million.

The tax, she explained, is meant to finance her plan for a Green New Deal: an ambitious programme of investments in carbon-free infrastructures and jobs, across various sectors, in order to decarbonise the economy by 2030. Ocasio-Cortez argued that, if taken in a historical perspective, this is far from a radical idea. Under Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency in the 1950s, top marginal tax rates were as high as 91%, coming from the 73% of 1920 and still as high as 70% in 1980

This proposal kick-started a heated debate, not only about the technical calculations of top marginal tax rates but also on the progressivity of tax systems and the role of different economic policy instruments in fighting inequality.

For the Washington Post, Jeff Stein – with the help of tax experts such as Mark Mazur (Tax Policy Center), Joel Slemrod (University of Michigan) and Ernie Tedeschi (Treasury Department of Obama’s White House) – tries to assess the implications of this tax policy.

Mazur calculates that it could raise $720 billion over the next decade, affecting 0.05% of the US population (around 16,000 households), although the estimate is likely to be much smaller because of the changing behaviour of the millionaires.

Paul Krugman steps into the debate in a New York Times op-ed, reframing Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal not as a radical socialist idea, but as an economically sound proposal, even moderate if viewed from a historical perspective.

Krugman quotes the Diamond-Saez (2011) calculation of the 73% optimal top marginal tax rate, as well as the ideal rate found by Romer & Romer(2011), which was higher than 80%. He challenges the Republican trickle-down arguments for tax cuts as based “on research by … well, nobody”, showing a non-negative correlation between economic growth and top marginal tax rates.

But what would be the economic justification for high top marginal income rates? Krugman builds the argument on diminishing marginal utilities and competitive markets. The former imply that an extra dollar of income is more useful to low-income families than to richer ones.

If each agent is paid her marginal utility, marginal top tax rates could even, theoretically, be up to 100%. The obvious tradeoff is that this would totally eliminate any incentive to work more, and hurt economic growth and innovation.

However, in case of non-perfectly competitive markets, where market failures such as monopolies and rents are present, the optimal marginal tax rate that maximises social benefits and aggregate welfare can be quite high.

John Cochrane replies to Krugman’s arguments by pointing out that the 70% calculations are based on arbitrary assumptions, and that Mirrlees (1971) calculates an optimal rate of 0% starting from different assumptions.

Cochrane writes that Saez-Diamond calculations do not include federal and local state taxes, and that the ‘disincentive’ argument does not account for human capital decisions that individuals might take: “And, like the decision to relocate, it depends on the total tax bite, not just the marginal tax bite. How much will I earn, after all taxes – what lifestyle will I lead – if I go to med school, or just stay where I am?”

Clive Crook, on Bloomberg, highlights the technical difficulties of calculating optimal tax rates, drawing attention to the fact that Saez & Zucman (2011) estimate a range between 48-76% where the optimal tax rate might lie. Also, Crook argues that, economically, it is a very questionable proposal; the risk is that the most successful entrepreneurs would emigrate, which would have costs higher than a loss of tax revenue.

But what Crook finds as the main problem with social-welfare-maximising policies is that, by grounding arguments in diminishing marginal utilities, they ignore questions of justice and liberty: “Whether some of the rich might deserve to be rich because of the work they’ve done, the risks they’ve taken, or the ideas they’ve come up with is irrelevant.”

Garrett Watson, at the Tax Foundation, underlines the risk that innovation processes will be hampered by higher marginal tax rates, quoting empirical evidence from a 2018 working paper by Charles Jones.

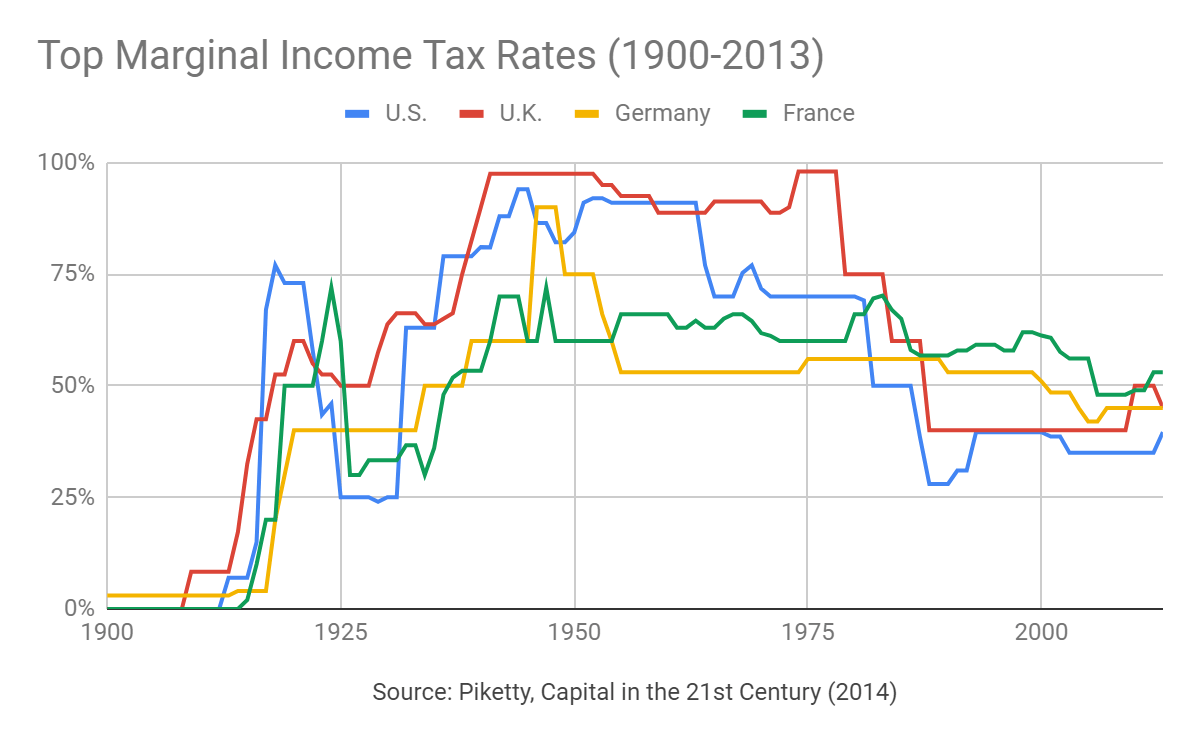

By contrast, Pasi Kuoppamäki, chief economist of Danske Bank A/S’s Finland branch, writes on the Hill that Nordic countries – although each helped by having a smaller population – have been able to make high taxation work well without harming innovation or incentives to work, while providing comprehensive welfare policies.

On Bloomberg, Noah Smith also endorses the proposal as “far from radical[,] and economically well-grounded”. And further, the key issue in his view is to go beyond this plan and reform the corporate and capital-gains tax systems, enlarging the base of high earners, and probably using wealth taxes.

Tyler Cowen, Michael Strain and Karl Smith join in a debate with Noah Smith on the economics of Ocasio-Cortez’s plan for a top marginal tax rate. They express several concerns about the effectiveness of such a plan in fighting inequality, a plan that would foster tax avoidance schemes and hamper innovation processes. Karl Smith points out: “What makes these systems redistributive is not punitive tax rates on the rich, but broad-based taxes that are used to fund a universal basic income for everyone.”

On avoidance, Aparna Mathur (American Enterprise Institute) explained that elasticities of high-income individuals, that have a much higher capacity to avoid taxes, would result in a government revenue 27.8% lower than the calculations made in a static scenario.

She proposes alternative solutions, such as an X tax – as suggested by Carroll and Viard (2012) – that would distort incentives less, or a carbon tax that also would also entail redistributive mechanisms (a point elaborated upon in a recent Bruegel Blueprint, written by Grégory Claeys, Gustav Fredriksson and Georg Zachmann)

The Bloomberg editorial board argued that Ocasio-Cortez’s idea is unwise, but worth discussing: Since the revenue needs of the government will rise in the future, both for social-security spending and for tackling climate change, they suggest to focus on closing loopholes and broadening the tax base before raising the rates.

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, of the University of California and Berkeley, address these concerns in an op-ed for the New York Times.They reply to the objections, showing that high top marginal tax rates are not correlated with slower economic growth (not only in the United States=, but also in Japan between 1950 and 1982).

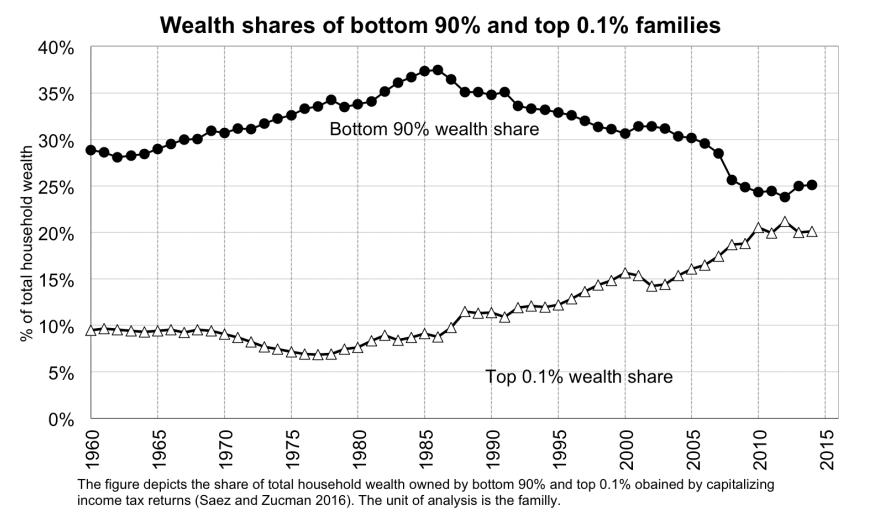

Their main point, though, is of a political nature. While in the US, incomes in the lower half of the distribution have stagnated for 30 years, the top 0.1% saw an increase of 300%, and the 0.001% of 600%.

In their view, proposals like Ocasio-Cortez’s have more to do with preserving a Japan-style liberal democracy, rather than paving the way for authoritarian reactions that result from years of negative income growth rates for a large part of the population.

If the concentration of incomes at the top coincides with concentration of power, higher tax rates are meant to shelter society from the dangers of plutocracy more than to finance investment plans or the welfare state.

This op-ed raised many reactions both from the left and from the right. Greg Mankiw criticised the political argument by commenting that most of the people that are earning high incomes earned their wealth honestly and have less political influence than commonly thought.

Chris Dillow, from a Marxist perspective, argues that the excessive political influence of the rich cannot be solved by a socialist-democrat state intervention, which would be insufficient to mitigate the failures of capitalism.

The debate was pushed, two days later, by the proposal of a tax reform by the Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren. This plan would introduce a wealth tax on the ultra-rich, a novel element in the history of US tax system.

The proposal is based on an analysis by Saez and Zucman: a 2% tax on the wealth that exceeds 50 millions, and an additional surplus tax of 1% on households with a net worth of more than $1 billion. These taxes would raise, according to their calculations, $2.75 trillion for a 10-year timespan (1.0% of GDP per year), affecting 75,000 households – a group smaller than the 0.1%. According to Saez and Zucman, the ultra-rich tax would be able to raise $212 billion for 2019.

They present an estimate by Piketty, Saez and Zucman (2018) that the tax burden on the wealth of the richest 0.1% households (including local, state and federal taxes) would be 3.2% for 2019, lower than the burden on the 99%, estimated at 7.2%. They claim that the ultra-rich tax would raise the burden on the 0.1% to 4.3%.

The revenue generated, Senator Warren explains in an interview, could be funneled into childcare and healthcare proposals, and to reduce student debt.

Yet the main objective, in the Senator’s words, is to help to level the power dynamics in Washington, reducing the amount of political influence that the economic elite can achieve: “It’s about making democracy work better, and it’s about making the economy work better… When you ask me about the centerpiece [of this proposal] it actually starts with an anti-corruption bill that tries to reduce the influence of money in Washington.”

Warren’s proposal was defended by noted tax experts and by Paul Krugman in the New York Times, arguing that, although radical, it would raise the average tax rates on the richest 0.1% to 48%, up from 36%.He added that it would be feasible – looking at Denmark and Sweden, where higher taxes did not lead to higher fiscal evasion – if adequately enforced.

On Bloomberg, while Noah Smith favoured a wealth tax meant to reduce income inequality as a better plan than many of the alternatives, Harvard’s law professor Noah Feldman expressed concerns as to the constitutionality of such a tax, shared by another candidate for the 2020 elections, Michael Bloomberg. As in the case of the Ocasio-Cortez proposal, many commentators put forward the argument that these type of taxes would hamper innovation and entrepreneurship.

European Trends

This chart from Piketty’s ‘Capital in the 21st Century’ depicts a decreasing trend in top marginal tax rates from a historical perspective, in a comparison between France, Germany, the UK and the US. The share of national income for the top 1% has been on the rise in many European countries.

The late Anthony Atkinson proposed a 65% top tax rate for the UK in ‘Inequality. What can be done?’ (2015), and also Piketty called for a rethinking of top marginal income rates in Europe.

Of course, as mentioned by Grace Blakeley, the situation on the European side is much more complex and would require capital controls to be effective.

However, if Europe is to accept the preoccupations for democracy expressed by Saez and Zucman, it should have a debate on high-income taxation.

Lots to chew over here but I will comment on three viewpoints here. The first is the Bloomberg editorial board where “they suggest to focus on closing loopholes and broadening the tax base before raising the rates”. I put that through my Bloomberg translator and it comes out the other end as “find more and ways to put taxes on wage-earners and even salary earners but not the billionaires!”

The second is Warren’s idea of how revenue “could be funneled into childcare and healthcare proposals, and to reduce student debt”. Perhaps I am biased but those recommendations seem to benefit the credentialed classes the most and only at best ameliorate the problems without going into any root causes. Besides – reducing student debt? Really? Throw more and more money down that multi-trillion dollar rat-hole? Is that her day job showing through?

At least Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in her proposals seems to be trying to restructure the American economy for some of the challenges – and realities – of the 21st century. Maybe what she is really saying is that it is best to make these changes now before as time goes we have no choice and not enough resources to carry it out.

This is a great post Yves, thank you.

Very timely. I am having a now month long discussion with my uni-aged son on marginal taxes and MMT. He called yesterday to discuss ideas for a paper he is writing following a classroom discussion on AOC’s proposal. Seems the Professor had to explain to a roomful of uni juniors the concept of progressive, marginal and flat tax rates. Sigh, one step at a time.

Sorry Rev, mistakenly replied to your comment here above.

“close loopholes” is a throwaway argument. It’s very much ‘lucy and the football’ stuff. We’ve seen the fits that private equity and hedge funds throw when someone dares to sniff around their beloved ‘carried interest’ loophole.

Lambert loves to point out the ‘public option’ concept serves the same function to water down demands for single-payer.

Let us choose medicare or the tapeworm if we want because real freedom is being able to chose the parasite we want!!!

One can hear the voices who will say, “If the government raises the tax rates, the wealthy will find a way around them.”

But if that statement were true, the wealthy would be fairly agnostic about tax rates going up.

Given the pushback from the wealthy who are quoted in the media, they do expect to feel some financial pain if rates go up.

Though Krugman is often a joke, his point is well taken in this debate. I sense that most Americans know they’re getting a very raw deal, but have trouble articulating why. Attacking economic rents should be a very powerful political play. The ongoing Purdue Pharma trials might open up the first battle front against such rents. Drug pricing in this country is already out of control, but the details leaking out about Purdue and Insys shed light on deeply corrupt elite behavior that destroys the lives of ordinary Americans. I can’t tell if it’s like the moment when it became politically feasible to attack big tobacco or not, but it feels like it to me. If rents and privileges in Pharma can be attacked, perhaps other monopolistic industries will face greater scrutiny and political consequences.

Krugman really prostituted himself via his loyalty to Team Dem as represented by Obama and Clinton. Many people noted a turn in a very bad way after he was invited to a small dinner with Obama. Krugman was very good in the runup to the crisis and through that early-mid 2009 dinner. Then he became an apologist. Maybe we are going to get some of the old Krugman back. I hope so; he was a good friend to the blog in its early days and I didn’t like having to start shredding him and later just ignore him (I’m clearly just an ankle biter, but still…).

He’s a kind of weathervane, in that sense. He was still decent at least as late as mid-2009, when he pushed for nationalizing the big banks.

He’s also a good demonstration of why the fall of the house of clinton was so important. As bad as the mccarthy-ite smearing around russia has been, it would have been so much worse with clinton in charge. Trump’s love/hate relationship with the permanent government has kept everyone in power from being united against the left resurgence.

Obama must have shown him the bed with the bloody horse’s head. Or maybe PK is just vulnerable to a master charmer and flatterer.

Do we ask economists to weigh in on whether there should be racial equality? Whether it should be legal for men to harass and assault women? Whether children should be separated from their parents at the border? Why look to them to answer whether and how to redistribute wealth?

Besides the fact that economists seem to contribute very little to any discussion outside of factually reporting data, does anyone believe they are not going to look for any reason they can find to undercut arguments that their patrons’ wealth should be redistributed?

It’s like asking Machiavelli if the Medici’s should be taxed at a higher rate.

Agree. Conservative Inc. – neo liberal, neo-cons do not want a real debate about taxes as it will likely go against the interests of their sponsors, and economists all pretty much belong to Conservative Inc.

My favourite is that the 1% pays most of the taxes. This may be true, but then the 1% gets most of the benefits of government. Who benefited from the Iraq war? Who benefits from the Military Industrial Complex?

Absolutely! Mega wealthy become so through inheritance, being very lucky, taking advantage of all the benefits of the country, the hard work of others and their own hard work and ambition for which they can be rewarded. The BS will fly but the question is simply does anyone really “deserve” to have a billion dollars more than 99.9% of everyone else for any reason.

Yes, the ultimate numbers are arbitrary but saying enough is enough at 10mm, 50mm, 100mm or whatever is not going to deincentivize the our next generation of “visionaries”. Only a narcissist or sociopath believes they are that more valuable than everyone else but we’ve grown many of them in recent decades.

As someone who studied Sociology, I’m angry that Economic has come to be used in the national discussion more than all the other social sciences combined (sociology, anthropology, psychology, political science, linguistics, history).

Sociology had a much higher profile in the 1960s back when leading sociologists like Talcott Parsons were cheerleaders for the (admittedly liberal, 70% top tax rate) establishment. Now that the social sciences have moved left and politics has moved right, the media aren’t inviting them on very much anymore, except for stars like Cornell West and Skip Gates.

I have also come to understand this in recent years starting with reading the work of David Graeber- an anthropologist from the London School of Economics.

I have a strong quantitative and math background and am always amazed that economists try and pass themselves off as quantitative scientists. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky won the Nobel in Economics (not a real Nobel, by the way) by proving that the fundemental assumptions of the trade are pure hookum. My opinion is that economists are just modern-day charlatans justifying wealth inequities for neo-cons.

Strangely enough my economics classes (introductory level macro and micro as part of studying accounting) made clear, both in texts and through the professors lectures that economics provides no insight or guidance whatsoever into questions of right and wrong or justice and that it leaves out many real world consequences as externalities. The best it can hope to do is make not-too reliable predictions of the strictly economic effects of a policy and those predictions are further restricted by what the models leave out. This was a small university in BC so I would assume we weren’t of great concern for neoliberal indoctrination but the professors also taught at SFU and UBC, the two big institutions here. I recall talking with my macroeconomics professor as we walked down the hall and saying “I’ve never before studied a field where it’s so common to hear experts say in effect: ‘That may be all well and good in practice, but it will never work in theory!’ and STILL be taken seriously. It got a good laugh out of him and he agreed with the essence of the statement.

As for Krugman – I agree he really went off the rails in 2016. He wasn’t alone. That was the year I found that many people I previously considered at least moderately rational to be as crazy as birthers and Iraq WMD true believers.

YV mentions this in the preface to his book “Foundations of Economics”. Human behaviours are mostly never factored in modern economics in the real world or taught in academic level (undergraduate courses and subjects).

If someone is going to attack big pharma, hopefully there will be a better result than the attack on big tobacco.

I don’t have the figures at my fingertips, but the court settlement against the tobacco companies was for a very large amount. After the settlement, it seemed as if all the stakeholders patted themselves on the back for a job well done and moved on. Big tobacco on the other hand raised the price of cigarettes right away around $.50/pack IIRC, and a quick back of the envelope calculation shows the tobacco companies got back all the $$$ they paid to settle extremely quickly, within a year or two. Not only that, but the money was supposed to be distributed to individual states and some states decided to take the lottery route and took a lesser amount up front rather than a higher amount doled out over many years.

It is a different situation with pharma – we’re talking about a harmful product vs an ostensibly helpful one with medications. And the problem is price gouging/rent seeking, whereas with tobacco it was health concerns, so hopefully a price cap or increased corporate tax rate (better yet, both) would be the result if there is to be one at all.

If these corporations are to be brought to heel, the punishment needs to hurt. It can’t be just a slap on the wrist, cost of doing business fine, which arguably was all that happened with the tobacco settlement.

Not a word about $21 trillion disappeared into the center courtyard and Power Rings of the Pentagram. Nor, I’ve lost track of the bidding, but maybe $7 trillion dumped into the laps of the Banksters. Along with how many million “homes” of mopes? And just a passing reference to the trillions “encumbered” by punitive and fraudulent “student loans.” Speaking of distortions, though of course the current state of the political economy is, by definition, “reality.”

That’s a lot of Big Macs and Large Fries…

I’ve been raising the idea of a cap on personal wealth on Twitter, arguing that the extremely wealthy use their money to buy the government, then dominate and subvert it to further enrich and benefit themselves. As noted above, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman apparently made similar points in their op-ed in the NYT:

Isn’t there also a quote going around about having either extremes of wealth inequality or democracy, but you can’t have both?

I like the strategy of emphasizing the political issues, rather than budgeting and revenue. If we make this debate just about the latter, that cedes the ground to economists and pundits. This should be a moral and political issue. What kind of society do we want to be?

So much hand-waving by alleged economists. Beardsley Ruml, New York Fed Cahair, had the goods on taxes in 1946:

Where has this been tried before? Answer: The United States from roughly the ’40s through the ’70s. Did the economy grow well? Yes, quite well, thank you. Now, you economists, your mission is to prove that this is theoretically impossible. Really, have we all fallen down the rabbit hole? Where is that little boy when you need him?

The last sentence assumes facts not in evidence. I remember the internet in the early ’90s. Almost all software was free. Innovaters released their programs in order to gain acclaim and admiration. Of course there were entrepreneurs like Bill Gates and Paul Brainerd and John Warnock and Dan Bricklin who wanted to make a lot of money, but there was also Phil Katz, who got comfortably well-to-do on PKZip without being an asshole about tracking down people who used the program without sending him a contribution. I firmly believe the people who are getting the kind of money that would be in a 100% tax bracket do not contribute to social welfare but instead cause a great deal of harm. I do not believe Sheldon Adelson got that rich legitimately.

seriously, and if adelman wants to leave I’ll help him pack.

The cold, hard reality that no one wants to discuss is that payroll tax rates need to be raised.

Social Security taxes for the employed are 6.4% (plus employer contribution of 6.4%). And only on the first $115k (approximately) of income.

Medicare taxes are 1.45% (plus employer contribution at the same rate).

So – 12.4% for 20 to 30 years of retirement. 2.9% for comprehensive health care for 20 to 30 years (conservatively).

It’s. Not. Enough.

The federal government spends all money into existence, including Social Security and Medicare dollars. Taxes simply extinguish dollars the government created in the first place. Taxes can reduce inequality, but they do not create federal revenues.

Raising wages without changing the taxation rates would also supply the added revenue you seem to think is necessary.

See Warren Mosler below.

Right, MMT, but the commenter I replied to seemed to think that payroll taxes and SSI premiums aren’t raising enough revenue. I merely suggested an alternative to increasing payroll tax rates.

How about we raise the payrolls before raising the taxes?

“…the government never has or doesn’t have any of its own money. It spends by changing numbers in our bank accounts. This includes Social Security. There is no operational constraint on the government’s ability to meet all Social Security payments in a timely manner. It doesn’t matter what the numbers are in the Social Security Trust Fund account, because the trust fund is nothing more than record-keeping, as are all accounts at the Fed.” (from SEVEN DEADLY INNOCENT FRAUDS OF ECONOMIC POLICY by Warren Mosler)

See here for explanation of how money really works.

If econ 101 suggests (outside neoliberal circles) that you tax what you want to reduce or eliminate, extreme rentier wealth seems an obvious choice. But why do we not tax pollution, or automation, or even talk about it? And why do we focus so much on how much we do or do not tax extreme wealth, but we have nothing to say about taxes on actual earned income for working people, or the way we have effectively penalized small business ownership and employment?

There ARE discussions, lots of them, to tax pollution. Look up the Carbon tax, which has been very much debated, including here at NC, and even in the mainstream press.

As for taxing automation, I agree, I havn’t heard much (or any) talk on a ‘robot tax’.

I tried using this argument many times during my economics schooling, and was told repeatedly that “interpersonal comparisons of utility are not allowed in positive (as opposed to normative) economic science.”* I’m actually a little surprised to see Krugman pulling this argument out (although it’s pretty irrefutable), as it opens the door to a whole lot of other policy arguments that our plutocrats would definitely not like the populace to be entertaining. Once you allow for interpersonal comparisons of utility, it’s obvious that maximizing overall utility would be achieved by taking a dollar from the richest and giving it to the poorest and repeating the process until everyone was….equal. Hence, why my econ profs would never let me stray too far down that line of reasoning.

*For the record, some of them would also argue that money, unlike everything else, is not subject to diminishing marginal returns since it can be turned into anything, and therefore can always be used to procure something with high marginal utility.

It is my understanding that roughly half of US discretionary spending goes to the military. No one seems to be discussing changing that ratio. Half of $720 billion over a decade is an additional $360 billion for the military. Think how many more people we can kill. We can continue the forever wars for another ten years at least. Win win. /s

Yes, I find this truly astonishing.

Looking at how much you pay in tax seems to be to be looking at the issue from the wrong end of the telescope. It is take home pay that matters. Which is kind of how it used to work in Scandinavia (before they caught the globalisation/privatisation/competition/mr markets bug). It may well be that Scandinavians pay (or paid) a higher amount of tax, but their take home pay and standard of living were much higher than in countries with much lower wages/lower taxes.

If I had a net annual salary where I could live quite comfortably, with decent housing, decent transport infrastructure, free education, free healthcare, decent pension provision etc., I would be quite happy even if my gross pay pre tax had been much more than that due to higher taxes.

Clearly, you have failed to get with the rich-person program.

Yes, what do I or 99% of the people care if they tax the 1% at a marginal 70% ? who cares?

Dean Baker also has an interesting article on this topic, underlining the importance of reducing pre-tax income inequality:

https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/pre-tax-income-is-a-problem/

What is essential is that the zeitgeist is rapidly changing for the first time since the Reagan years. It has for decades been politically incorrect to make the observation that some people have more money than they can possibly deserve. If Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, Michael Dell and Howard Shultz worked so hard and were so brilliant, who are we to question their rewards?

Now that is becoming OK to speak the obvious, we are finding that the majority of Americans believe that redistribution of wealth (and its purchased political power) needs to take place. The billionaires (sorry . . . people of means) are reacting like the bankers did a decade ago to Elizabeth Warren with profound narcissistic stupidity and ignorance of the world around them. The economists and the others who pick up the crumbs dropped by the super-rich are in a frenzy to defend the status quo. Are we really going to pay attention to their BS any longer?

Lastly, we need to focus on taxing and redistributing wealth. It has been shown repeatedly that income taxes have little impact on redistributing wealth between generations and classes and may even have adverse effects – for example black athletes who earn substantial income for a short period of time. There is $30-$40 trillion of 1% wealth that needs to be be brought back to the public domain before it is transferred to billionaire babies.

Warren Buffet gave $10 million to each of his kids and said if they can’t get by with that it’s their problem. Seems more than fair to me in terms of a policy and hardly the Russian revolution but it will be a huge fight to even get there.

The most effective tax avoidance scheme is buying congresscritters and having them lower the tax rate for you, and while they’re at it pass the medical industrial support tax known briefly as the ACA so that rich peoples premiums for their numerous doctor visits are ameliorated through subsidies from people who can’t afford to go to the doctor (affordable care for who?)

Neoliberalism is becoming a more and more obvious failure…

Smugnorant. That’s my favorite new word that perfectly describes the billionaire snowflakes that have to rig everything from elections to Super Bowls to placate their fragile egos. We can thank Reagan for spawning the new rash of billionaires by lowering the marginal tax rate.

“Limiting inequality, not revenue collection, is precisely what taxation is for, the core progressive purpose of taxes—including a graduated income tax and the crucial estate tax—in a capitalist society. (And we are here talking about a capitalist society.) As Piketty and other have shown, it is probably the single most effective instrument of “non-reformist reform” for achieving that purpose.

To be crystal clear (because it sneaks in), when I say that taxes are used to “prevent gross inequality,” that does not mean “to fund social programs”; it means, simply and elegantly, to prevent people from becoming too rich.”

MMT has given us the opportunity to decouple federal spending from taxes. Americans have been overtaxed for far too long. It’s not taxpayer money, it’s PUBLIC money, newly issued into existence by Congress every time it spends.

MMT founder Warren Mosler calls for the end of the FICA tax and to raise SS rates to $2,000/mo.

MMT advocate Claire Connelly makes a case against the income tax.

It seems that rather than rely on the government redistributing wealth, which is obviously going to be even more inefficient since they excepted FASAB 56 (https://home.solari.com/fasab-statement-56-understanding-new-government-financial-accounting-loopholes/) and it is no longer necessary to report specifically were the money went, (perhaps to line their own pockets, who will know?). Wouldn’t it be better to redesign the system so that redistribution is less necessary? I’m no economist, but Samuel Adam’s idea of a free market (https://www.ratical.org/ratville/MichaelHudson-JunkEcon.html), that is taxing unearned income at a very high rate rather than to tax earned income seems like the most efficient, and ethical way to go about redistributing wealth in our current system by shifting the earning power. Besides, how can the “right” argue against fee market capitalism? You could still make a profit as a parasite*, but this would significantly reduce the blood letting and perhaps breath enough life into the economy for it to survive. Although I suspect the extravagant demands of the wealthy may still be too much for the working class to bear, especially since it is not the imaginary world of economics that ultimately matters, but the the ecosystems that we depend on to survive. Here again the reduction or removal of rentier income would better align investment with actual resources rather than just claims on resources which, while infinite at least until someone blinks aren’t a very good feedback mechanism. Yes, this realignment could slow the growth of debt and thus the number of people running on treadmills just for the sake of creating debt, but if the goal is to get the pigskin in the end zone then perhaps we also restructure our laws and trade agreements to favor cooperation & open source such that the teams are working together. This would make the task rather trivial and certainly not worth paying to watch, but put significantly more challenging tasks in the realm of possibility, like dealing with ecosystem collapse, global warming, poverty. Isn’t the point to create a world where everyone can spend there days dreaming of what could be, since we have to imagine that world before we can create it. It is not that we should stop supporting those that imagined and created the magnificent world in which we are living, but that was yesterday and there is a whole new set of challenges today that require a whole new way of imagining the world and those currently in charge can’t even imagine it, none the less make it happen.

*That is not to malign parasites as they are a necessary part of any ecosystem; just as with predators, and prey for that matter, their numbers must be kept in balance for the system to remain functional. Note: I’m not talking about the actual people only the roles they are playing.