By Walter E. Fluker, Professor of Ethical Leadership, Boston University. Originally published at The Conversation

Director Martin Doblmeier’s new documentary, “Backs Against the Wall: The Howard Thurman Story,”is scheduled for release on public television in February. Thurman played an important role in the civil rights struggle as a key mentor tomanyleadersof the movement, including Martin Luther King Jr., amongothers.

I have been a scholar of Howard Thurman and Martin Luther King Jr.for over 30 years and I serve as the editor of Thurman’s papers. Thurman’s influence on King Jr. was critical in shaping the civil rights struggle as a nonviolent movement. Thurman was deeply influenced by how Gandhi used nonviolence in India’s struggle for independence from British rule.

Visit to India

Born in 1899, Howard Washington Thurmanwas raised by his formerly enslaved grandmother. He grew up to be an ordained Baptist minister and a leading religious figure of 20th-century America.

In 1936 Thurman led a four-member delegationto India, Burma (Myanmar), and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), known as the “pilgrimage of friendship.” It was during this visit that he would meet Mahatma Gandhi, who at the time was leading a nonviolent struggle of independence from British rule.

The delegation had been sponsored by the Student Christian Movement in India who wanted to explore the political connections between the oppression of blacks in the United States and the freedom struggles of the people of India.

The general secretary of the Indian Student Christian Movement, A. Ralla Ram, had argued for inviting a “Negro” delegation. He saidthat “since Christianity in India is the ‘oppressor’s’ religion, there would be a unique value in having representatives of another oppressed group speak on the validity and contribution of Christianity.”

Between October 1935 to April 1936, Thurman gave at least 135 lectures in over 50 cities, to a variety of audiences and important Indian leaders, including the Bengali poet and Nobel laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, who also played a key role in India’s independence movement.

Throughout the journey, the issue of segregation within the Christian church and its inability to address color consciousness, a social and political system based upon discrimination against blacks and other nonwhite people, was raised by many of the people he met.

Thurman and Gandhi

The delegation met with Gandhi towards the end of their tour in Bardoli, a small town in India’s western state of Gujarat.

Gandhi, an admirer of Booker T. Washington, the prominent African-American educator, was no stranger to the struggles of African-Americans. He had been in correspondence with prominent black leadersbefore the meeting with the delegation.

As early as May 1, 1929, Gandhi had written a “Message to the American Negro”addressed to W.E.B. DuBois to be published in “The Crisis.” Founded in 1910 by DuBois, “The Crisis” was the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Gandhi’s message stated,

“Let not the 12 million Negroes be ashamed of the fact that they are the grandchildren of slaves. There is no dishonour in being slaves. There is dishonour in being slave-owners. But let us not think of honour or dishonour in connection with the past. Let us realise that the future is with those who would be truthful, pure and loving.”

Understanding the Idea of Nonviolence

In a conversation lasting about three hours, published in The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Gandhi engaged his guests with questions about racial segregation, lynching, African-American history, and religion. Gandhi was puzzled as to why African-Americans adopted the religion of their masters, Christianity.

He reasoned that at least in religions like Islam, all were considered equal. Gandhi declared, “For the moment a slave accepts Islam he obtains equality with his master, and there are several instances of this in history.” But he did not think that was true for Christianity. Thurman asked what was the greatest obstacle to Christianity in India. Gandhi replied that Christianity as practiced and identified with Western culture and colonialism was the greatest enemy to Jesus Christ in India.

The delegation used the limited time that was left to interrogate Gandhi on matters of “ahimsa,”or nonviolence, and his perspective on the struggle of African-Americans in the United States.

According to Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s personal secretary, Thurman was fascinated with the discussion on the redemptive power of ahimsa in a life committed to the practice of nonviolent resistance.

Gandhi explained that though ahimsa is technically defined as “non-injury” or “nonviolence,” it is not a negative force, rather it is a force “more positive than electricity and more powerful than even ether.”

In its most practical terms, it is love that is “self-acting,” but even more – and when embodied by a single individual, it bears a force more powerful than hate and violence and can transform the world.

Towards the end of the meeting, Gandhi proclaimed, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

Search for an American Gandhi

Indeed, Gandhi’s views would leave a deep impression on Thurman’s own interpretation of nonviolence. They would later be influential in developing Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance. It would go on to shape the thinking of a generation of civil rights activists.

In his book, “Jesus and the Disinherited,”Thurman addresses the negative forces of fear, deception and hatred as forms of violence that ensnare and entrap the oppressed. But he also counsels that through love and the willingness to nonviolently engage the adversary, the committed individual creates the possibility of community.

As he explains, the act of love as redemptive suffering is not contingent on the other’s response. Love, rather, is unsolicited and self-giving. It transcends merit and demerit. It simply loves.

A growing number of African-American leaders closely followed Gandhi’s campaigns of “satyagraha,” or what he termed as nonresistance to evil against British colonialism. Black newspapers and magazines announced the need for an “American Gandhi.”

Upon his return, some African-American leaders thought that Howard Thurman would fulfill that role. In 1942, for example, Peter Dana of the Pittsburgh Courier, wrotethat Thurman “was one of the few black men in the country around whom a great, conscious movement of Negroes could be built, not unlike the great Indian independence movement.”

King, Love and Nonviolence

Thurman, however, chose a less direct path as an interpreter of nonviolence and a resource for activists who were on the front lines of the struggle. As he wrote,

“It was my conviction and determination that the church would be a resource for activists – a mission fundamentally perceived. To me it was important that the individual who was in the thick of the struggle for social change would be able to find renewal and fresh courage in the spiritual resources of the church. There must be provided a place, a moment, when a person could declare, I choose.”

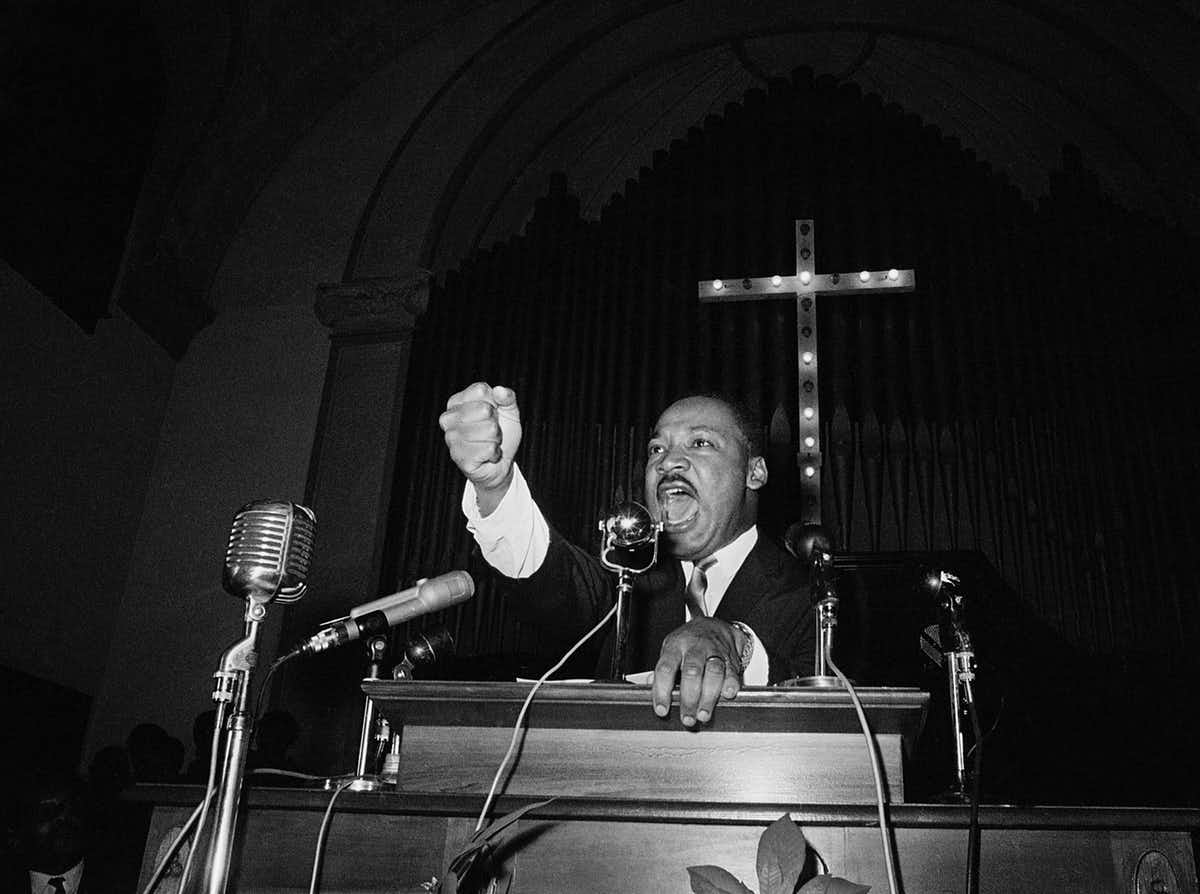

Indeed, leaders like Martin Luther King did choose to live out the gospel of peace, justice and love that Thurman so eloquently proclaimed in writing and the spoken word, even though it came with an exacting price.

In his last letter to Martin Luther King, dated May 13, 1966, Thurman expressed his regret for the time that had elapsed since he and King last spoke. He ended the short note with a rather foreboding quotefrom the American naturalist and essayist Loren Eiseley,

“Those as hunts treasure must go alone, at night, and when they find it they have to leave a little of their blood behind them.”

King, like Gandhi 70 years ago, fell to an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968.

Nonviolence turns our ingrained conceptions of power on its head.

I have always wondered, what creates the space for a Gandhi or a King, versus the millions of non-violent activists over time and space who have simply be summarily murdered, tortured to death, disappeared?

verify first, i’ll venture a reply (sort of) to your great question:

maybe that space is something with such complicated roots that we just don’t get to know.

as for those millions who know they risk being murdered, tortured to death, disappeared, yet choose to act anyway–what creates the space in which they act?

they create it, when they act.

of course, there is more to it than that.

the fact that so many have actually made that choice is pretty amazing, isn’t it?

In the case of India, the British had never had a large occupation army there. They ruled more by inserting themselves into the top rung of a complex nation that had not yet taken on the tightly defined modern form. It also helped that India had been ruled by outsiders for centuries before the British.

Thus, their rule was more dependent on their perceived legitimacy and they did not have the manpower to rule by sheer force. That created the space for Gandhi’s use of non-violence.

In the case of the civil rights movements, a number of factors were at work. One, the deep South was seen by much of the rest of the country as not quite really us. This made it possible for the rest of the country to see white violence in the South for what it was.

Second, given attitudes in the South and in the rest of the country, it was quite clear that violent protest would have been suicidal. Third, the United States was constrained by its Cold War competition with the Soviet Union during an age of decolonization. The “soft power” cost to the US of being seen as on a level with South Africa would have been enormous. JFK was quite conscious of this and spoke of it explicitly. Remember also Vaclav Havel’s comment that the US war in Vietnam kept communism alive an extra 20 years (by providing camouflage for the moral bankruptcy that the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia would have otherwise exposed).

Finally, mechanization of Southern agriculture after WW2 meant that the South was no longer economically dependent on hyper-exploited African-American labor.

None of this is to detract from the historical efforts made by millions of Indians and African-Americans to attain more freedom. It only points to some factors that enabled those freedom struggles to take a non-violent form.

On a completely contrary note, it is worth being aware that another factor behind the support in India for the non-violent path was that it not only got the British out, but it kept the rest of India’s social structure, particularly Brahmin dominance, largely intact. A violent independence movement would almost invariably depended far more on the efforts of ‘lower’ caste people.

if Gandhi inspires people towards good then it is good. People do need inspiration beyond “Greed is good”.

However it is bit of a stretch to make him the cause of India’s independence.

It was rumored earlier, but later declassified papers from British army and Clement Atlee’s letters told a different story, They ruled India basically because of the Indian Army, which was almost at a point of rebellion due to the influence of SC Bose (Mr Gandhi’s bete noire) who had created a rogue Indian National Army outside India which fought alongside the Japanese.

The Indian Army had rebelled once before (in 1857) and led to huge loss of lives on both sides. The Brits did not want a replay.

Gandhi may not have been able to convert the Indian masses at large to his creed of ahimsa. But that the national movement led by him had widely and deeply influenced them to strive for their independence cannot be denied. And these masses increasingly included the ranks of army, police and the bureaucracy. Gandhi’s ahimsa lent him an aura of sainthood and contributed to his leadership. Even his critics who did not necessarily agree with his methods rallied around him. He was able to galvanize the whole nation to the cause of independence. Entire nation was on the move. It was this that daunted the British and not just the likelihood of a new army mutiny.

Even S. C. Bose’s small splinter Indian National Army was a product, albeit a deviant one, of the larger national movement. Bose was formerly a leading figure in Gandhi led Indian National Congress. It is doubtful also how effective Bose’s small army aligned with the then rapacious Japanese would have been able to deliver India from colonial subjugation. Would not triumphant Japanese have become new colonial masters?

on the same topic as this post, here is an interview with sarah azaransky, author of “this worldwide struggle: religion and the international roots of the civil rights movement” (2016), a book i recommend and consider important:

https://relpubs.as.virginia.edu/this-worldwide-struggle-a-qa-with-dr-sarah-azaransky/

MLK carried thurman’s book “jesus and the disinherited” with him and read it often.

it is still in print and should be required reading today for activists and anyone concerned about “how” we are to meet the disaster we are currently in.

i am sad to see how little comment has appeared at NC so far on this post about howard thurman. i consider it essential if we are to carry anything worthwhile into our collective future that we inform ourselves of the history it recounts. taught by thurman and others, MLK in turn taught people how to choose a level of aliveness and ethics regarding their own victimhood that they did not think themselves capable of. and then they chose it.

a lot has changed since then–the black church, for one. but the lessons of this history and these writings are very much needed now. before we discount them as no longer relevant, we should at least make sure we understand them.

another great discussion is the following piece by professor azaransky, who teaches social ethics at union theological seminary. she has thought more deeply about the current dilemma than most. this piece must be read all the way to the end.

https://tif.ssrc.org/2018/02/28/listening-in-our-disasters/

excerpt:

“For Ella Baker, listening was a democratic norm. Baker was among the greatest democratic practitioners of the last century. Listening is a theme in Barbara Ransby’s exemplary biography of Baker. From her earliest organizing in the 1930s, everywhere Baker went, she listened. In casual conversations, Baker, “a careful reflective listener [could] ascertain what those people, if organized, might be prepared to do politically.” Later, as an advisor to young activists in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Baker insisted SNCC organizers sit on porches for hours, spending weeks in a Mississippi Delta town so they might begin to understand people and the shapes of their lives—all this before official organizing work could begin.”

Thanks for those links, I will follow up and look at them. I too am a bit disturbed by the lack of NC readership response.

Sometimes a person creates a space by virtue of the force of their personality, and perhaps in a lucky few cases that space is big enough to protect them for a while.

I worry a lot about what seems to me the shrinking space in the US, especially with the digital surveillance of….everything.

I guess sometimes the outrage is so large within a person that they see no option but to act, even knowing it could be futile and/or fatal.

thanks for listening.

i am not sure any one person can actually create such a space, or if it can only happen when more than one come together. we tend to idolize “great leaders” and that is often encouraged by media of all kinds. all those in the immediate circle of that designated leader, who surround and support and carry forward the teaching and the action, and without whom the leader could accomplish nothing, seem to become better known only later. often after they die, and their papers go to the archives, and ph.d. students start writing dissertations about them.

how people learn, how they become able, to step up together in the face of a terrifying institutional opponent to articulate an essential moral truth, as MLK’s nonviolent army did, in such a way that they were “coffin ready”, as MLK put it, interests me greatly. and people are doing it now as we converse, all over the world. just thinking of this is the only antidote i know of to the despair of these times.

so maybe it has to do with that–maybe this kind of action really is the only antidote to that kind of despair. maybe it’s not just a matter of outrage, though that is an essential part of it, but also a matter of desperately needing the medicine that only a direct existential confrontation with the present evil can provide.

Compared to military violence, nonviolent action has acres of space, considering it allows virtually anyone to practice it at just about anytime.

Nonviolent action focuses on the individual’s partial or complete withdrawal of their sources of power for the powers that be. Done singly or in small groups this method is mainly symbolic, yet, as Gandhi realized, it still has a salualatory effect on those practicing it.

For nonviolent action to become a revolutionary force, it needs to be widesprad and strategic. Think general strike or mass noncooperation. It requires no less discipline or strategy than military warfare. This is, however, where the space becomes tighter.

Nonviolence has worked as a political force many times in our history. See Gene Sharp’s work on the matter.

And it has one superior trait that armed conflict continually fails at: it can change the dynamic between nonviolent actors and the armed police and military by not employing the “kill or be killed” dynamic. This dynamic is used by militaries the world around, but can lose its power when faced with determined nonviolence. Revolutions are not won unless the armed forces “sit it out” or change sides.

So, Gandhi declares that, in Islam, all are considered equal; the moment a slave accepts Islam he obtains equality with his master; there are several instances of this in history; but that is not true for Christianity.

That was Gandhi’s view.

Now, Islam and Christianity share similar scriptures and are burdened with similar histories of militarism. So, what in the world caused Gandhi to make such a disparaging declaration about Christianity?

politics.

he wanted muslim followers (and muslims detested him because of his hindu saint pretences – this was to have severe consequences at partition of india). christians in india were too few.