Yves here. This article pre-supposes that readers understand that most leveraged lending is taking place as a result of private equity, via two routes. First, private equity funds use a great deal of borrowed money when buying companies. One of the biggest sources is so-called leveraged loans, which are normally originally made by banks, but are quickly syndicated to other players, mainly investors (in the old days, foreign banks were major syndicate loan buyers). Second, one of the biggest buyers of leveraged loans are credit funds…which are managed by private equity firms. Mutual funds and life insurers are also significant buyers of leveraged loans.

Note that in the US, regulators have been reluctant to regulate investors like public pension funds, institutional investment funds, endowments and foundations. Maybe it’s time to re-examine that “grownups can take care of themselves” assumption when their excesses can blow back to the overall economy.

By Dirk Schoenmaker, Professor of Banking and Finance at the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam. Originally published at VoxEU

Leveraged finance is booming, just as it was in the run-up to the Global Crisis. As before, central banks are bystanders, with only banking instruments for macroprudential policy. this column argues there are unused regulatory powers that can rein in investment funds. A cross-sectoral approach would help to rein in the current unsustainable levels of leveraged finance.

Some movies feel like a replay. Can we do anything to prevent a sad ending to the current boom-bust cycle, which resembles earlier financial crises? The deal-making engine driving M&As, fuelled by high valuations and cheap leveraged finance, is running at full power.

Central bankers and supervisors warn about overheating to no avail. Supervisors take some action on banking, but that drives business to alternative investment funds. After the Global Crisis, Brunnermeier et al. (2009) warned against this sectoral focus. They called for a system-wide approach to macro-prudential regulation. In earlier work (Schoenmaker and Wierts 2015), my co-author and I showed how supervisors could apply a minimum leverage ratio to alternative investment funds (hedge funds, for example) to slow the growth of their balance sheet. This instrument has not – yet – been activated.

Euphoria

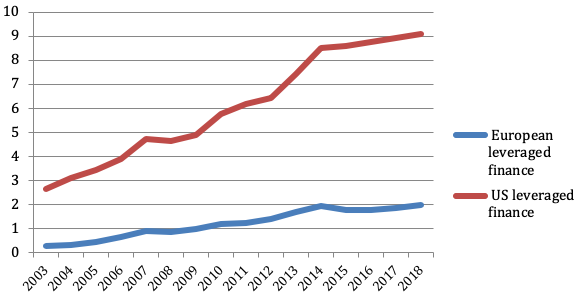

Leveraged finance is made up of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds for non-investment-grade firms that are highly indebted. These firms are often owned by private equity. Figure 1 shows that leveraged finance has doubled since the global crisis.

Figure 1 Leveraged finance in Europe and the US (US$ trillion)

Source: BIS (2018).

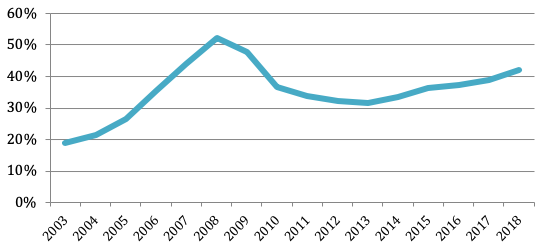

Moreover, the share of leveraged loans is increasing, just as immediately before the global crisis (Figure 2). Debt financing with thin equity stakes is risky. When the economy turns, equity is quickly wiped out, leading to failure.

Figure 2 Leveraged loans as share of total leveraged finance (%)

Source: BIS (2018).

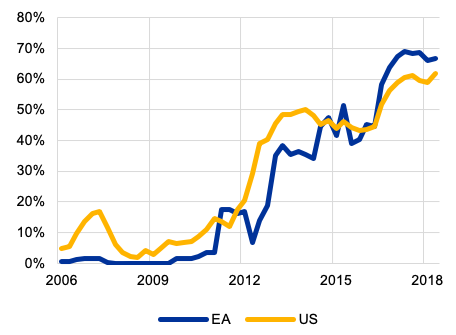

A final point of worry is the increasing share of covenant-lite leveraged loans, which is rising fast to about 60 to 70% (Figure 3). Increased amounts of financing, plus loosening of standards, are both signs of a boom with strong competition and overtrading. In the search for yield in the current low-interest environment, both banks and investment funds are driving the leveraged finance market.

Figure 3 Covenant-lite leveraged loans (% of leveraged loans)

Source: ECB (2018).

Minsky’s (1986) financial instability hypothesis distinguishes five stages, from boom to bust:

1. credit expansion, characterised by rising assets prices

2. euphoria, characterised by overtrading

3. distress, characterised by unexpected failures

4. discredit, characterised by liquidation

5. panic, characterised by the desire for cash

We are now well into the second stage of euphoria, close to the third stage, in which there is an accident waiting to happen that will cause a collapse of the leveraged finance market, and possibly the wider financial system.

Current Sectoral Approach

Central banks are warning that current loan volumes and loose standards are not sustainable (Bank of England 2018, ECB 2018, Goel 2018). But nobody is listening. Business continues as long as the music plays.

Supervisors give guidance to banks, for example, that a company’s gross debt should not exceed six times its EBITDA. But they are not addressing non-bank financial intermediaries, such as insurers, pension funds, investment funds, hedge funds, and private equity. The Bank of England (2018) shows that about one-third of leveraged loans are held by banks, one-third by insurers, and pension funds and the remaining one-third by hedge funds and open-ended investment funds.

As we would expect in differing sectoral regulations (Cizel et al. 2019), there is anecdotal evidence that leveraged finance business is moving to non-banks in response to tightening banking requirements. There is therefore a need for a sector-wide approach.

System-Wide Approach

In earlier work (Schoenmaker and Wierts 2015), my co-author and I showed how a minimum leverage ratio could slow the growth of the balance sheet of financial intermediaries. With a fixed leverage ratio (i.e. equity/total assets), equity is the constraining factor for growth of total assets.

Banks (and insurers) face such a leverage ratio. The Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (2011/61/EU) enables supervisors, among other things, to maximise the leverage of investment funds, including hedge funds and private equity. A maximum leverage requirement (where leverage equals debt/equity) is equivalent to a minimum leverage ratio (Schoenmaker and Wierts 2015).[1]. A minimum leverage ratio of 5% is, for example, equivalent to a maximum leverage of 19.

So far, securities supervisors have not activated this leverage requirement for investment funds. A major problem for sectoral regulation is that different supervisors follow different approaches, each one using the language that sector, and so are not aware of similarities. Non-bank supervisors also tend to be more lenient than bank supervisors on the prudential front.

Macroprudential supervision needs to be applied system-wide to avoid regulatory leakages (Cizel et al. 2019). First, we propose to maximise leverage of investment funds that are involved in leveraged finance, through collateralised loan obligations or high-yield bonds. This forces securities supervisors to use the powers they have. Second, the guidance on leveraged finance for the borrowing companies (gross debt should not exceed six times EBITDA) should be given to all suppliers of finance. In the Netherlands, we have good experience with applying borrower-based requirements (such as maximum loan-to-value ratios for mortgages) to all financial intermediaries.

A cross-sectoral approach could help macroprudential authorities to rein in the current unsustainable levels of leveraged finance.

See original post for references

https://www.oaktreecapital.com/docs/default-source/memos/the-seven-worst-words-in-the-world.pdf?sfvrsn=4

Always a good idea to pay attention to Howard. This from Sept. 2018.

chewiitup

Thank you.

Central banks, with their many years of Quantitative Easing and negative real interest rate policies, are not without responsibility in this matter. The dainty policy pirouette that pushed up the market price and lowered interest rates of junk bonds in late December might have bought the time for both debtors and creditors, but that’s about it. Have seen wildly varying estimated totals of this debt, so I appreciate the charts from the BIS and the summary of Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis. Seems to me that the nature and volume of this debt, including ‘covenant-lite’ leveraged loans, bears a family resemblance to the subprime mortgage debacle that contributed to the financial crisis in 2008.

Is this one reason why vampire capitalists are able to take over healthy companies, suck out all the value, and screw the employees?

Yes. It is also similar to subprime mortgagees that got bundled and suddenly became investment grade.

Many of the institutional investors have to hold bonds, but that is unappealing with ZIRP. So people are willing to create bonds with higher yields that are more appealing. As a small investor, if I want equity-like returns and risk, I buy equities. I own bonds as a diversifier and to reduce volatility.

But I don’t have requirements on what I can own, other than what the IRA and 401k rules are. The institutional investors have rules (written or by convention) defining what their portfolios need to look like, so they are the targets for the salesmen. So the 2008 financial crisis was largely driven by the smart money. It is likely that the next crisis will also be driven by the smart money as they don’t seem to have learned anything other than they will be bailed out.

this is why you need positive interest rates.

at ZIRP the leveraged speculators will buy all the productive assets, and when they run into trouble they will force a bailout on the rest of the population “otherwise the people will lose their jobs”.

Or at least regulators that regulate. I have trouble accepting that ZIRP implies or is the cause of this financial orgy. I have read this many times and still don’t buy it. IMO wealth concentration rather than ZIRP is closer to the causes, or a combination of both.

There were financial orgies before “zirp” and will be after “zirp”. Creating artificially high rates won’t help.

Although I fully agree with the proposition of this article – i.e. central banks are essentially bystanders watching unconstrained leveraged debt markets – I wish I could agree with the author’s recommendation. Lawmakers and macroprudential authorities have allowed the growth of obscure private capital markets that thrive on misrepresentation and dishonesty. A fundamental tenant of markets is information symmetry, i.e. relevant information is known to all parties of a transaction. Institutionalization of this tenant was central to creation of the SEC and securities regulation on disclosure. Debt markets today assume sophisticated debt players can assess credit risks and allocate capital using their own expertise. However, in our era of easy money, it is caveat emptor, and too many money managers value deal origination over deal quality.

This reminds me of JD Alt’s latest insight about the viability of capitalist businesses. That they should be analyzed according to some stricter assessments as to just how much profit they can be expected to reasonably gain. To curtail all this leverage to nowhere. And to limit the race to the bottom for capitalism itself. Equity has been loosely defined and regulated to be everybody’s free lunch. Even a good product cannot last forever and a frivolous one is simply destructive.

Believe the prevailing view of ‘insider’ economists with policy influence is that we remain in a period of ‘secular stagnation’ in which “even improved financial regulation is not necessarily a good thing — and that it may discourage irresponsible lending and borrowing at a time when more spending of any kind is good for the economy.”

Saving for one’s retirement, the education of one’s child, for medical care, financial support for oneself or one’s family members due to aging or injury, a vacation, etc. is deemed to be economically damaging.

https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/16/secular-stagnation-coalmines-bubbles-and-larry-summers/

Assuming that this remains the prevailing view of economic and monetary policy makers, then I feel that the nation’s monetary system needs to be fundamentally restructured. This also raises the question in my mind of whether capitalism can work in a debt-based fiat monetary system.

“Business continues as the music plays” reminds one of the remark CEO Chuck Prince made to the FT in 2007:

“[A]s long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.”

Our knowledge of the basics is worse than it was 5,000 years ago.

When mankind first learned to write, there were “Jubilee Years” as they had already learnt that compound interest rises faster than society’s ability to pay it. To ensure society didn’t fall apart they had some debt forgiveness built in.

Today we are unable to comprehend that as compound interest is an exponential function it will rise faster than society’s ability to pay it and we think all debt can be paid.

That pretty much sets the scene for what must be one of the most ridiculous eras in the history of mankind.

To expect anyone to grasp more complicated matters like the dangers of securitisation is just absurd.

We released the power of finance, which was the power of debt and didn’t have a clue what we were doing. We used future prosperity to inflate asset prices today with bank credit, e.g. real estate.

It’s daft really, but that’s all it was.

We didn’t realise what we were doing because:

1) Neoclassical economics makes you think inflating asset prices creates real wealth

2) No one understood the monetary system and how bank credit really works

Even Ben Bernanke thought banks were financial intermediaries. He couldn’t understand debt deflation or how bank credit is a claim on future prosperity.

In 2014 the central banks started revealing the truth about how banks really work, starting with the BoE.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

How neoclassical economics became the economics of globalisation is a mystery as it’s always had the same problems.

The 1920s roared with debt based consumption and speculation until it all tipped over into the debt deflation of the Great Depression.

No one realised the problems that were building up in the economy as they used an economics that doesn’t look at private debt, neoclassical economics.

1920s – debt fuelled boom

It feels like there is lots of money about because there is, money is being created from all the new loans.

1930s – debt deflation of the Great Depression.

It feels like there isn’t much money about because there isn’t, money is being destroyed by all the repayments.

Debt deflation is caused by a shrinking money supply.