Yves here. While most readers probably accept the idea that letting banks run wild did more for financiers than the real economy, it’s still important to test the idea empirically.

By Josh Ryan-Collins, PhD, Head of Research at University College London’s Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. He was previously Senior Economist at the New Economics Foundation (NEF). Originally published at Evonomics

In academic and policy circles there is deep mistrust of public sector involvement in credit allocation, much more than in the credit allocation decisions made by commercial banks. This mistrust continues, despite the financial crisis of 2007–08 demonstrating the huge dangers of a deregulated credit market. Whilst, post-crisis, financial regulators have begun to develop policies aimed at reducing lending in certain sectors, calls for proactively directing finance to support desirable sectors of the economy have largely been ignored.

In a new UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP) working paper, co-authored with Dutch economists Dirk Bezemer and Lu Zhang and Frank van Lerven, we examine the theoretical, historical and empirical evidence around credit policy and its effects on the allocation of credit.

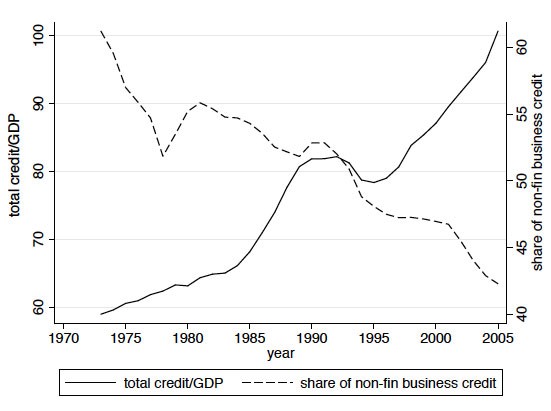

Our motivation, aside from the crisis, is the remarkable ‘debt shift’ in advanced economies over the past 40 years which has seen banks move away from their primary textbook role of lending to non-financial firms to support productive investment. Whilst total bank credit has roughly doubled relative to GDP since the early 1970s in advanced economies, the share of credit supporting firms has actually fallen, from 60% to 40%. The vast expansion in lending has been mainly to support households to buy houses and, to a lesser extent, consumer goods and the purchase of financial assets.

Total credit and business credit share in advanced economies, 1973–2005. Data is averaged across 17 advanced economies.

Mortgage and other asset-market lending typically does not generate income streams sufficient to finance the growth of debt. Instead, the empirical evidence suggests that after a certain point relative to GDP, increases in mortgage debt typically slows growth and increase financial instability as asset prices rise faster than incomes.

These new empirical findings support a much older body of theory that argues that credit markets, left to their own devices, will not optimise the allocation of resources. Instead, following Joseph Schumpeter’s, Keynes’ and Hyman Minsky’s arguments, they will tend to shift financial resources away from real-sector investment and innovation and towards asset markets and speculation; away from equitable income growth and towards capital gains that polarises wealth and income; and away from a robust, stable growth path and towards fragile boom-busts cycles with frequent crises.

This means, we argue, there is a strong case for regulation, including via instruments that guide credit. In fact, from the end of World War II up to the 1980s, most advanced economy central banks and finance ministries routinely used forms of credit guidance as the norm, rather than the exception. These include instruments that effected both the demand for credit for specific sectors (e.g. Loan-to-Value ratios or subsidies) and the supply of credit (e.g. credit ceilings or quotas and interest rate limits).

In Europe, favoured sectors typically included exports, farming and manufacturing, while repressed sectors were imports, the service sector, and household mortgages and consumption. Indeed, commercial banks in many advanced economies were effectively restricted from entering the residential mortgage market up until the 1980s. Public institutions — state investment banks and related bodies — were also created to specifically steer credit towards desired sectors.

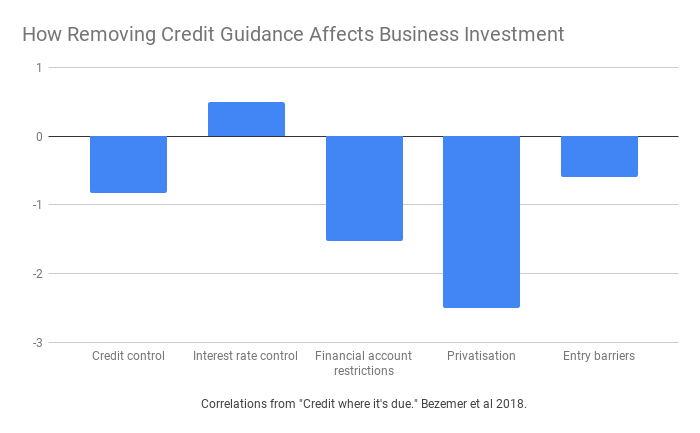

The financial liberalisation and deregulation of the 1980s saw the gradual removal of credit guidance and credit control policies which were seen to distort the efficient allocation of capital. This was a key element of the ‘Washington Consensus’ pushed by the World Bank and the IMF to developing countries. Many State Investment Banks were also privatised.

Our empirical investigation of the relationship between credit policy and credit allocation examines two time periods with different samples. Firstly, for the 1973 to 2005 period, for advanced economies, we find that the liberalisation of credit markets and removal of credit guidance is significantly associated with a lower share of lending to non-financial firms, supporting the Schumpeter-Keynes-Minsky hypothesis.

In a second sample sample, for the 2000 to 2013 period, we use a wider sample of countries, including emerging markets. In this period, there has been somewhat of a shift by financial regulators back towards the use of credit controls, following the emerging market economy crises’ of the late 1990s and early 2000s and, in advanced economies, following the global financial crisis of 2007–08. However, for this period we do not find a significant relationship between the introduction of these ‘macro-prudential’ policies and the share of lending to non-financial firms.

We hypothesise this may be related to post-2000 interventions being primarily focused purely on financial stability concerns rather than economic growth and the need to steer credit towards productive sectors of the economy. We conclude that both types of credit policy may be needed.

The debate about the pros and cons of credit guidance is not a closed case and the empirical evidence presented in our paper raises as many questions as it answers. More detailed empirical and qualitative research, examining examples where credit guidance policy has been both successful and less so, is required going forward.

However, given the huge challenges facing modern economies, not least the need to rapidly transition to low-carbon economies, financial policy-makers should be encouraged to experiment with credit guidance policies to support sustainable and inclusive growth, while also maintaining a focus on financial stability issues. To do so, greater collaboration between central banks and ministries of finance and industrial policy will likely be necessary.

Read the full working paper:

Credit where it’s due: A historical, theoretical and empirical review of credit guidance policies in the 20th century

Josh has written a good book on the financialization of British real estate. He cites an article by my colleague Dirk Bezemer, with whom I’ve written a number of articles. NC readers may want to look at the writings of both these guys.

A reference would be appreciated.

There are paragraphs in this article that should be written in the walls of the oval office and equivalent places elsewhere

This post seems to be in lock-step with yesterday’s “Other People’s Blood” post. The insanity of the 80s. But, to be clear, It was policy too. We need an Insane-o-meter to measure in real time when we are totally off our rockers. The role of symbolic stability that money and finance serve to create is such a sad, but durable, illusion. Because it’s laughable to think that analysis uses logic so illogically – as an analysis of “financial stability.” Which doesn’t exist. Social stability does exist – but the two are so loosely connected as to be independent. There’s a time lag of denial and/or exuberance before anybody even realizes, Hey, something isn’t working here. Maybe a policy to prevent delusion is what we need.

Consider Miami during Reagan’s time and Hudson’s experiences [waves] ….

I met one of the pilots who flew guns to the Contras out of a small airfield in Louisiana. He was a real nutcase “True Believer,” who also got off for “accidentally” killing his (admittedly rotten, I met him too,) son in law. They went out hunting and M tripped over a log, fell down and his shotgun went off. Unfortunately, the son in law was in the field of fire. Strangely enough, someone else that I knew inside the Sheriff Department later told me that the joke running around the place was that M’s pump shotgun “accidentally” went off twice into the son in law’s back. That was the tale the number of pellets taken out of the body told. If anyone could be described as having “snake eyes,” M could.

Just down the road from the little airport near Abita Springs which sent so many belligerent bibles over to Central America is the site of the Dixie Ranch, where the CIA trained many of the Cubans used in the Bay of Pigs attack.

The gunrunning was also being done out of the airport in Mena, Arkansas. A certain William Jefferson Clinton was governor of Arkansas during most of the Iran Contra affair.

Miami, on the other hand, has always been crazy. I grew up there, I should know. Why, the locals used to joke about Dick Nixon visiting his “bud” Bebe Rebozo on Key Biscayne so often.

Yep. There is a lot of crazy to be found in the Deep South of the United States.

“There is a lot of crazy to be found in the Deep South of the United States.”

Like saving beaver at the crack of dawn after Christmas eve before white shoe law man has an important docket that morning … something about SF dude family stuff tragedy…

Indeed;

“Died in livin’ color,”

“Lived in black an’ white.”

Did I mention hall way … decorum … sigh …

What happens when fear goes so far it doesn’t – isn’t viable to the eye anymore and only …. a few with mental teeth like nubs … can see it.

Living with fear. It’s the modern way.

“The Helot’s Guide to Etiquette.”

Whats an indavidual to do …. when the environment said …

Hi ho. Just woke back up. Running on a very irregular sleep/wake pattern lately. (Mirroring the wife’s pattern. What fun.)

Yes, Pragmatism is an artifact of environmental factors, ain’t it.

Greetings from the Crazy South.

Richard Werner also talks (great speaker) and has written books worth reading IMHO about credit guidance and how for example it once allowed the Asian tigers to emerge.. while changing the industrially focused policies, particularly at BoJ, has been detrimental to Japan’s economy.

Also:

“In academic and policy circles there is deep mistrust of public sector involvement in credit allocation, much more than in the credit allocation decisions made by commercial banks.”

– might then credit guidance by adapted where possible in a profit oriented system to broadly support progressive goals that a wide admission of MMT for public benefit might allow? Kind of like a less controversial complement of MMT?

My worthless 2bob is as some have noted: the managerial … cough MBA indoctrinated running everything, have watched more than a few industries lose knowlage about – doing a thing – as the experience was made redundant or took a hike – insert fresh malleable try hard’s that will sell it all for a lifestyle buff so they can Flexian [tm] their way to the top.

Everyone around here should know the part equities played in all this.

Deplorado … just a heads up … be careful with Werner and do your homework, bit duplicitous.