Yves here This post may seen a bit abstract, but it attempts to map out how to increase democratic accountability and counter the influence powerful private sector interests have over major international institutions. While another response has been to try to bolster national sovereignity, that can’t go very far in a world where economies smaller than the US and China (or ones that are or have been forced to autarkies, like India, Russia, and Iran) operate through regional trade blocs.

The shortcoming of nationalism as a response to how the global wealthy have succeeded in using their ability to arbitrage markets to foment a race to the bottom in environmental, regulatory, and labor standards is that it often winds up being dominated by right wing interests that play upon xenophobia and by design don’t address the problems of mobile capital and long supply chains. So “embedded internationalism” isn’t quite a solution, it at least helps clarify the nature of the problem and where some approaches might lie.

By David Adler (@davidrkadler), a political researcher. Originally published at openDemocracy

Progressives must urgently develop a new vision for international institutions, or they will be reshaped in the image of our opponents.

This article is part of a series by openDemocracy and the Bretton Woods Project on the crisis of multilateralism. The views expressed are those of the author’s only, and are not necessarily representative of either organisation.

A coup is underway at the World Bank, and no one is watching. On Friday, 5 April, the executive directors of the world’s most powerful multilateral bank voted unanimously to appoint David Malpass — a staunch supporter of Donald Trump and fierce critic of “globalism” — as its new president.

The decision honoured the ‘gentleman’s agreement’ that allows the US president to install an ally at the helm of the bank — despite a hard-fought campaign to allow for an open selection. The direction of the bank will now be set by a man who believes that multilateralism has “gone substantially too far” to obstruct the America First agenda.

But beyond the pages of the Financial Times, these proceedings have barely dented public discourse. Malpass will begin his five-year term without a single street protest or a single press statement by a major political party.

The silence is puzzling. The World Bank, like its partner the IMF, has huge costs. The United States alone contributes $155 billion of taxpayer money to the bank — more than double what it spends on food stamps each year. These institutions also have huge consequences. As the Bretton Woods Project has revealed, the World Bank and the IMF continue to demand austerity and drive privatization across the global south. The scale and scope of these institutions suggests that their management should invite serious public scrutiny.

But they do not — and this is not an accident. International institutions are intentionally insulated from democratic demands. A very generous reading would suggest that this is because international institutions must be protected from the vagaries of the electoral cycle. Their democratic deficit is, according to this view, a virtue. International institutions could never withstand grassroots intervention.

But this strategy has now — clearly and dramatically — backfired. By closing themselves off from public view, these institutions made themselves easy targets for political entrepreneurs seeking a scapegoat for their domestic crises. The European Union, the United Nations, NATO — international institutions have become the bogeymen of populist movements around the world. There are important reasons to revile these institutions, but they are rarely those cited by the blustering Brexiteers or MAGA chuds.

In other words, if democracy once appeared as the great danger to the integrity of international institutions, technocracy has revealed itself as their true existential threat.

It is time, then, to bring the politics back in — not only as a strategy for building a new internationalism, but also as a necessary defence against the alt-globalist agenda that is climbing its way to the very top of our international institutions, one quiet coup at a time.

II.

But what, exactly, does this mean? How should we make sense of the struggle to reclaim international institutions? And what are the strategies to get there?

To answer these questions, it is helpful to set out the terrain.

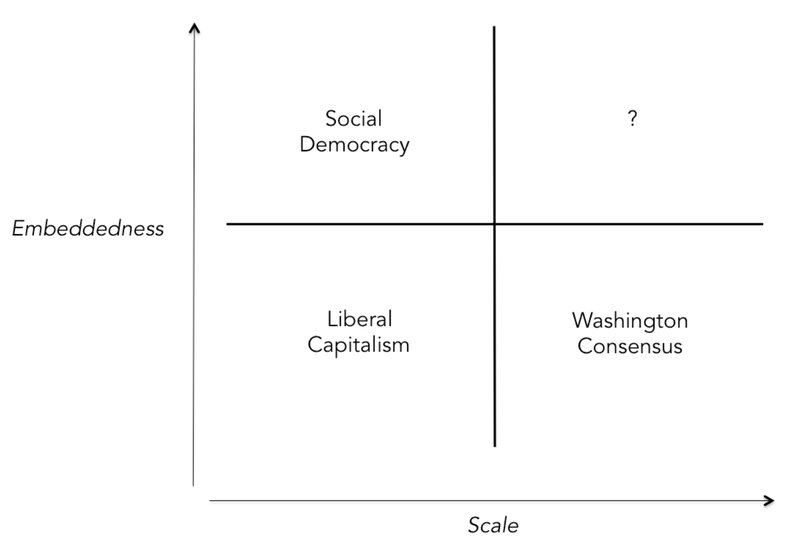

I map the political economy of this struggle across two axes. The first is embeddedness: the extent to which markets are anchored in society. At one end is laissez faire capitalism, a free market unconstrained by moral considerations and economic regulations. Everything here is a commodity, including human life and the earth itself. The axis therefore moves upward toward decommodification, enshrining protections that limit the exploitation of resources like labour and land.

The first axis could also be described by its more modern inverse, financialisation: the extent to which elements of society present themselves as opportunities for financial speculation. To disembed is to financialise. To re-embed is to definancialise.

The second axis is scale: the level at which political activity is organized, from the national to the global.

Figure 1: The Axes of Internationalism

The map tells the story of a century of political conflict.

In its first half, the primary conflict occurred along the axis of embeddedness at the national level. A Gilded Age of capitalism witnessed the emergence of a consolidated national bourgeoisie, which built new institutions — peak associations, political machines — to disembed the economy. New workers’ movements then organized their own institutions at the national level — trade unions, political parties — in order to demand that governments combat inequality, provide decent jobs, and enshrine new rights to services like healthcare and goods like housing. Social democracy was born.

The latter half of the century activated the second axis. Having been tamed at the national level, capital went global, chasing opportunities in countries where the economy was far less constrained by embedding regulations. Of course, they did not encounter those countries in a natural state of disembeddedness. Rather, this process required the construction and mobilization of institutions that would clear the way for international investors.

The World Bank and the IMF, dangling the carrot of development resources, were refashioned to play this role. Promoting their ‘Washington Consensus,’ these institutions acted as vehicles for a global disembedding of the economy — both directly, in the cases of countries that agreed to the terms of structural adjustment; and indirectly, in the cases of countries who were forced to compete with them, applying pressure to undo the progress of the social democratic arrangement.

In other words, capital and labour have been caught in a game of cat and mouse across the quadrants of this map. Capital first scurried to enshrine its interests at the national level, then labour caught up and contested. Capital scurried to reconstruct the global economy in its image — but no social movement has emerged to contest it at that scale.

Indeed, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008, new political movements tended to point toward more familiar quadrants of the map. Right-wing populists from Nigel Farage to Donald Trump heralded a new model of national neoliberalism: shifting back on the axis of scale while demanding a deeply disembedded economy — Singapore-on-Thames, or the Trump tax cuts. Their left-wing opponents similarly called to reassert the primacy of the nation, but with much stronger social protections. Globalization, both agreed, had gone too far.

But in calling to return to the nation, the new social democrats failed to learn the lessons of the past. Capital, now globalized, has the upper hand against individual nations that hope to contest it. It can slither between borders, and hide out in havens. The mouse is out of the bag — now we must train the cat to find it.

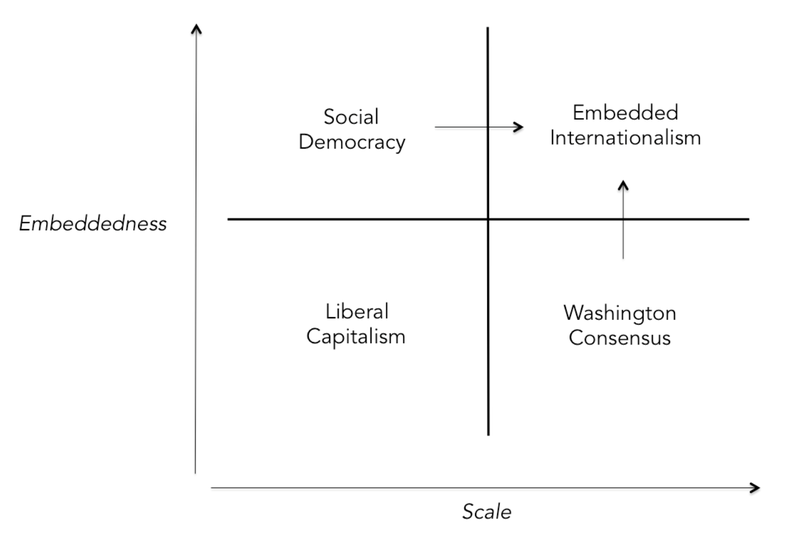

In other words, our task is to push into the missing quadrant — to re-embed the institutions that govern the global economy: an embedded internationalism.

Figure 2: Strategies for Embedded Internationalism

But how, exactly, do we get there?

The map provides some ideas. In particular, it suggests two lines of strategic attack that we must pursue simultaneously.

The first is contestation: igniting a transnational debate that links social movements around the world in a single conversation about our international institutions — scaling up along the x-axis. The last half-century of globalization has made our national debates increasingly alike in content, focused on transnational issues like trade and finance in a global economy. But they remain fragmented in form: few social movements or political parties coordinate their platforms across borders. Scaling up means integrating these national debates to match the scale of their issues.

In a word, we need to get international institutions back on the ballot, calling on progressive politicians to outline their own vision for institutions like the World Bank, IMF, ILO, and the UN.

The second is democratization: demanding reforms that shift power away from the technocrats and toward regular people — re-embedding along the y-axis. We might start by killing the ‘gentleman’s agreement’ that allows the US and the EU to install their allies at the head of the World Bank and IMF, respectively. But we should also call to introduce democratic representation at the heart of these institutions, allowing countries to elect members of their governing council.

These may sound like pipedreams. But the perverse power structure of our international institutions means that a progressive president in the White House or prime minister at Number 10 could radically shift the momentum in favour of these proposals. After all, countries like the US and the UK hold key purse strings. If contestation can push their governments to table serious democratization reforms — to raise the voices of small countries around the world — these proposals will get a hearing.

Of course, not every institution can be salvaged in the process of re-embedding the global economy. Consider the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a wing of the World Bank Group that oversees private sector investment in developing countries. The IFC today acts as little more than an engine for financialisation, turning public wealth into financial products that can be traded across the financial sector. A bold agenda for global re-embedding would simply abolish the IFC full stop.

But new institutions can be proposed in its place. Progressives around the world are crying out to coordinate their demands and fight together to constrain the global oligarchy. All it takes is one progressive government with the courage — and the imagination — to propose new institutions to do so: worker ownership funds, green transition institutions, tax justice authorities. Even proposals that are introduced unilaterally will soon attract international participation. If the US builds it, in particular, they will certainly come.

Critics like Adam Tooze suggest that efforts to reclaim and transform the international institutional order are “quixotic,” because the global economy is too fluid, too volatile to be ordered in this way.

But laissez faire was planned, and globalization was, too — and now David Malpass is preparing to remould them. Progressives should take a page from the playbook of their opponents and develop a plan to roll out new institutions for the re-embedding of the economy, rather than simply relying on ad-hoc interventions to roll back the mistakes of the past.

III.

On the eve of Trump’s inauguration, the United States was poised to retreat from its role as the driver of global disembedding. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was dead. America First was alive. And virtually every international institution had earned the ire of the incoming president. “If the word ‘isolationist’ has any meaning, [Trump] qualifies as one,” the FT reported.

But now we can see that the right-wing populist project is more dangerous than it first appeared. Far from rejecting international institutions — scaling back from the global level to the national one — Trump and his allies are mounting their take-over. The objection to the Washington Consensus, it turns out, was not that it did not serve their interests. It was that it did not serve them well enough. This is what David Malpass means when he says that multilateralism has gone “too far.”

It is all too easy for progressives to dismiss international institutions as the machinery of global capital, and to focus where power appears closer at hand.

But we cannot afford to play peek-a-boo politics: just because we don’t talk about the World Bank and the IMF doesn’t mean that they are not still there. As the mess of Brexit has definitively demonstrated, power at the international level is a prerequisite for sovereignty much lower down, particularly in countries that lack the geopolitical weight to set the international agenda. We must therefore develop our own vision of international institutional change, or else they will be reshaped by our opponents.

The first steps of this strategy are now clear. We must contest globally, reminding people and parties around the world that international institutions are theirs for the taking. And we must demand democracy, reigniting our imagination about how to transform them.

But the prospects for such a transformation are far better than they may appear. The unanimous appointment of an anti-globalist like David Malpass at the helm of a hyper-globalizing institution like the World Bank should be an inspiration to all of us — that radical change may be around the corner.

Let’s work out what’s wrong with their half-baked neoliberal ideology and its underlying economics, neoclassical economics.

“Everything is getting better and better look at the stock market” the 1920’s sucker that believed in free markets

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Irving Fisher 1929.

The 1920’s neoclassical economist that believed in free markets knew this was a stable equilibrium.

Better shelve this for a few decades until everyone has forgotten.

Now everyone has forgotten we can use it for globalisation.

I don’t know who the architects of globalisation were, but I do know they weren’t very bright.

Just because people have forgotten what’s wrong with neoclassical economics, it’s still got all its old problems.

Running an economy on neoclassical economics.

The 1920s roared with debt based consumption and speculation until it all tipped over into the debt deflation of the Great Depression.

No one realised the problems that were building up in the economy as they used an economics that doesn’t look at private debt, neoclassical economics.

What’s the problem?

1) The belief in the markets gets everyone thinking you are creating real wealth by inflating asset prices.

2) Bank credit pours into inflating asset prices rather than creating real wealth (as measured by GDP) as no one is looking at the debt building up.

Let’s have another go.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

Whoops!

1929 and 2008 look so similar because they are; it’s the same economics and thinking.

The global economy never stood a chance.

The neoliberal ideology told elites what they wanted to hear and they couldn’t resist it.

It is much easier to see the flaws in Left wing ideologies.

They are put together in a few minutes down the pub, on a Friday lunch time.

Let’s wipe out the Bourgeoisie to create a better society. Another couple of minutes to work out the details and Pol Pot would be ready to go.

The Right put a lot more time and effort into it.

In 1947, Albert Hunold, a senior Credit Suisse official looked for a group of right wing thinkers to form the Mont Pelerin Society and neoliberalism started to take shape. They spent decades searching for suitable ideas to bolt together into a right wing ideology. They made sure all the ideas fitted together and were logically very consistent.

Only time would reveal the flaws in this cleverly, crafted ideology.

2008 – “Oh dear, the global economy just blew up”

Time’s up.

Add another ten years to work out what’s wrong.

For those of us that can be bothered to make the effort, our experts gave up very quickly.

2008 – “How did that happen?”

It was a black swan.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

There it is.

It’s the debt that neoclassical economics doesn’t consider.

Once you get the idea things are wrong at the base it gets easier.

Everyone assumes our current knowledge has built up over time as we learn from past mistakes.

With economics and the monetary the system there is too much to lose from allowing knowledge to develop in the normal way.

Our knowledge of privately created money has been going backwards since 1856.

Credit creation theory -> fractional reserve theory -> financial intermediation theory

“A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence” Richard A. Werner

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521915001477

Everything had been going well for 5,000 years and then the classical economists turned up. Those at the top had been living in luxury and leisure, while other people did all the work.

The European aristocracy were just the same, they lived in luxury and leisure while other people did all the work. The Classical Economists realised they were being maintained by the hard work of everyone else.

The Classical economist, Adam Smith:

“The labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Economics was always far too dangerous to be allowed to reveal the truth about the economy.

How can we protect those powerful vested interests at the top of society?

The early neoclassical economists hid the problems of rentier activity in the economy by removing the difference between “earned” and “unearned” income and they conflated “land” with “capital”.

They took the focus off the cost of living that had been so important to the Classical Economists to hide the effects of rentier activity in the economy.

The landowners, landlords and usurers were now just productive members of society again.

Our knowledge of economics and the monetary system are fundamentally flawed.

Real wealth as measured by GDP? Wealth is relative,not absolute. Consider a balance sheet with money on the right side and productive human time+ effort on the left side e.g. the human productivity balanced by machine and other physical assets. Asset inflation per the value of human contribution.

Further, statistics only applies to the data set and not to any individual data, in this topic, not to an individual’s economic/social standard. A graph of GDP against Gini Index would be interesting . . . at least to me.

hour.

The IMF have done the same as the FED.

They think that PhDs in neoclassical economics provide the best expertise there is, but neoclassical economics ignores the money supply, debt and the role of banks in the economy.

This is why they make the mistakes they do.

The IMF predicted Greek GDP would have recovered by 2015 with austerity.

By 2015 Greek GDP was down 27% and still falling.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

The “private debt” component was going down with deleveraging from a debt fuelled boom. The Troika then wrecked the Greek economy by cutting the “public debt” component and pushed the economy into debt deflation.

It’s not even hard really; you just need to understand the monetary system and where the money supply comes from.

I believe that’s telling the Bosses what they want to hear.

Neo-classical economics assumes money has an intrinsic value which it does not have in this fiat money electronic transfer economy. We now live in a (Game of) Monopoly world in which every year every person “passes go” but every person does not receive the same welfare payment.

Like in Monopoly, the wealth is not in collecting the cash payments but investing in the real estate and infrastructure. A “lucky” person could conserve his cash and come out ahead in the first rounds but will lose the game. The game is won by investing in real estate.

“It says that democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible: we can combine any two of the three, but never have all three simultaneously and in full.” [Dani Rodrik]

Corollary theorem.

Doesn’t calling something a “corollary theorem” suggest a proof exists somewhere????

Isn’t Adler providing a two-variable theory, looking for data to test?

If the author wants to rebut Tooze, who claims that trying to tame international financial institutions is quixotic because the global economy is too fluid to be ordered, he should reconsider what I’ve quoted. I’m still very much paddling about in the shallow end of the pool in this area. But Helleiner’s States and the Reemergence of Global Finance suggests that the supposed taming of national capital was, as we know, only temporary, and that the breakdown of that national-level taming was directly connected to chasing opportunities internationally.

In the post-WWII period, it seems that much hinged on whether or not capital controls regulating international flows could be maintained to prevent national capital from fleeing/undoing national economic projects. E.g. if France wanted to keep interest rates low to encourage local investment, they would need to limit capital flight to higher interest areas. At Bretton Woods both Keynes and White stressed that capital controls would need to be cooperative — enforced by both the originating and destination countries — if they were to be effective. Helleiner charts how, over time, the US and Britain, with the US increasingly in the lead, came to steadily oppose cooperative controls. For Britain this reflected the drive to preserve some of its economic swat by freeing the City from controls. In the US this reflected the gradual erosion of the hold New Deal-friendly policy makers had on institutions like the Treasury department, ceding to financial interests organized around a “liberal internationalist” orientation centered in New York.

So we have two-fer for elites: the possibility of progressive domestic politics relies on national economic regulation which becomes increasingly difficult once international capital flows are unregulatable. Achieving hot flow freedom internationally also tends to clear the decks of domestic opposition. To address Yves’ point, from this angle it seems that the only way to go is to ensure that cooperative capital control efforts can occur. I strongly doubt that this can come about via international organizations that don’t have a strong domestic sounding board. Otherwise you’re going to wind up facing black helicopter paranoia that cannot distinguish between beneficent and malign international controls. But at least we do have a well-established policy paradigm for talking about these matters. It’s unfortunate that the author doesn’t draw on it more strongly and instead — to put it harshly — makes it seem as though we’re flying by the seat of our four-celled tables.

Here’s the point of the article:

“These may sound like pipedreams. But the perverse power structure of our international institutions means that a progressive president in the White House or prime minister at Number 10 could radically shift the momentum in favour of these proposals…”

Same as plan for last few hundred years or since the appearance of the conservative/liberal bisection of what passes for “democracy.”

The author’s idea may have surprising supporters of an older DC with the current defanging of the Acela Corridor and MSM crowd. Giving voice back to the voters and states, and reducing the influence of permanent insiders by cutting off the flow of tax (or MMT) funds to their budgets, would level one type of playing field a little bit.

Look what happened to marginal news outlets when their trough got closed a few months ago and wannabe tyrants had to try to find other jobs. With low unemployment, opportunities abound even without having to ask Paper or plastic, or Would you like fries with that. Drinks in that hopping Georgetown spot might have to be skipped due to new budget realities.

The domestic example could start a trend toward more sustainable international progress and away from IMF-prescribed austerity for the ills of the world. An audit or two of those big international institutions would go a long ways toward greater transparency and more beneficent behavior.

Then add in potential benefits from a more peaceful world through the likely resolution of the North Korea issues and reduction of the malign influence of the Bolton Neo-Con wing. Sometimes I think that a few Cabinet and advisor posts are filled to put on display the opposite of what is really desired to highlight the countercurrents.

Imagine if people had more control over Representatives and Senators, and had their voices heard. Those high-polling programs like M4A could get a chance. Declutter the agendas to make the processes work.

It is quite possible that natural events will make international institutions impossible: when there are too many natural emergencies caused by climate change, then survival will become the mantra for all, rich or poor. Immense wealth seems to change the character of the wealth holders so that incremental accumulation of wealth and power becomes the sole activity and goal of the wealthy who also happen to control international institutions of today. Wealth controls international institutions and international institutions control the wealth–a no-win situation.

This was interesting. Made me imagine the illogical end stage of financialization – we are almost there now. It would be total commodification of the planet and the people. But it doesn’t seem to be possible. That would be my question, Why not? All the pieces are in place, but it’s just not working. Whether or not Trump is a right wing neoliberal on steroids is debatable as well. I think he is looking at all the dysfunction in a state of confusion. One of the things that need to be “democratized” is money itself. The irony is unavoidable at this point that private money, via the auspices of the World Bank, is trying to insinuate itself into sovereign, national projects in PPPs and other ways and to establish a contract with sovereign authorities to insure their returns. As Paulina Tcherneva tells us: Sovereignty is money. But one thing we have yet to analyze is just what happens when everything has been allowed to be financialized, in spite of sovereignty, and written up in one-sided contracts for the protection of private money. This is nuts, because the foundation of this thinking is nonsense. Money is not a private phenomenon. And never will be. If it could be, real resources would not ever become a problem. Private money, and a surplus of it, will destroy its own value pretty fast. It doesn’t deserve an extortionate contract with a sovereign to protect it’s delusional investment and returns. I agree with Adler that we should begin to democratize the World Bank by “simply abolishing” the International Finance Corporation. It is a magic trick that does nothing more than transmogrify real wealth into private money. For starters. But I don’t have my hopes up. It is more encouraging to realize that private money has so few options left that it is pretending to play nice with sovereign democracy of its own volition. And contrition maybe.

Likewise, textbooks, define money as a medium of exchange and a store of value. It is as a store of value that the problems with money begins, inflation, deflation and the like. Yes, money is a store of value up to a point. Beyond that point it becomes a problem, is a drag on productive capacity and can be used to manipulate the political economy. Whereas government is in possession of the power to create a limitless money supply, the tax system should be used not for revenue, but to rein in the deleterious effects of money as a store of value. The current low velocity of money in our current economic system is a sure sign that the function of money is now dominant as a store of value and not a medium of exchange, which exchange should be its principle function.

Money is no longer a store of value. Fiat electronic money has no intrinsic value.

The concepts of Local Manufacture and Import Substitution, coupled with state run medicine and pensions, would drive the economy more equitably.

It would demolish the giants multinationals.

And its been done before.

Taking over the global financial institutions is the stated goal of yanis varifoukus and DiEM25

No mention of the violence used to maintain the international order?

The institutions are always presented as if they were built to be able to accommodate the people or the commons and yet decade after decade it’s “oops, didn’t mean for that to happen.”

They are violent institutions embedded with violent people and any theorizing should include this and understanding of monetary systems.

Global economic integration is not compatible with democracy. To explain why this is so, just think about what happens when a group of people decide they want out.

The only way to build a more just world social order is to insist on that order being made up of strong states.

The path towards democracy in England began with the Magna Carta, which was actually an effort by the petty potentates to preserve their own privileges. However, by protecting those privileges, the English lords inadvertently laid a basis for the protection of the rights of others, eventually all the way down. Incidentally this didn’t harm English unity.

In our globalized world, we don’t need “embedded internationalism.” We need the various petty sovereigns of the world to demand a Global Magna Carta. Drag the globalists off to Runnymede, and tell them that they are going to have to show some more respect for the nations.

It won’t have to make sense in a law or poli sci class. The Magna Carta never made any philosophical sense, either.

Labor historian Erik Loomis, who writes (a lot) over at LGM, posts occasional pieces on labor conditions abroad (e.g. Bangladesh). One often reads in long threads how “yes yes, but globally, workers are doing better as a whole.”

I think it’s important to understand that that’s an interim state and not the final goal, which is to force all working people worldwide downward to the lowest common denominator. This article provides a general framework for how this process has occurred and will continue to occur unless …

One of India’s best writers and the first to win a nobel prize in literature from asia, Rabindranath Tagore, has written a lot about internationalism. – https://www.wochikochi.jp/english/relayessay/2015/06/between-nationalism-and-internationalism-the-political-philosophy-of-rabindranath-tagore.php