Yves here. This article has an important finding, that having health care industry professionals in the family is a plus for longevity in lower-income households. However, it also has a disturbing “blame the poors” subtext, in that it assumes that having relatives in the health biz leads to better lifestyle choices, as if not having an uncle who is a doctor means someone is more likely to swill Coke and eat Big Macs.

This piece utterly looks past what one of my highly credentialed friends who came from a blue collar family and has a lot of nurses and later MDs in his family: that even when he was as fully armed as a medical professional in dealing with medical professional and institutions on behalf of his father, who suffered from dementia, he would be treated completely differently than his physician brother. Medical professionals take other medical professionals far more seriously than laypeople. My friend’s case showed that having a medical professional relative act as an advocate made a big difference in responsiveness, which can affect outcomes.

On a more mundane level, having a medical expert readily accessible also helps in getting advice, not on lifestyle, but in dealing with accidents or anomalies. It makes a big difference to be able to call a family heath professional and ask if they should visit the doctor or even go to the ER over a worrying health condition. Even in a system with free health care, seeing a doctor is still a tax on your time, something the authors ignore, and low income people are typically more time-poor than well-off people in a country like Sweden with enlightened workplace policies.

By Yiqun Chen, Petra Persson Assistant Professor of Economics, Stanford University and

Maria Polyakova, Assistant Professor of Health Policy, Stanford University. Originally published at VoxEU

Poorer people have worse health at birth, are sicker in adulthood, and die younger than richer people. Apart from socioeconomic status, exposure to informal health expertise may also affect health. Using data from Sweden, this column examines whether having a health professional in the family has an effect on health. It concludes that differences in exposure to informal health expertise can account for some of the observed patterns of health inequality, even in an environment with universal health insurance and equal formal access to healthcare.

Poorer people have worse health at birth, are sicker in adulthood, and die younger than richer people. Indeed, growing evidence across various disciplines reveals stark correlations between health capital and socioeconomic status (e.g. Marmot et al. 1991, Case et al. 2002, Deaton 2002, Currie 2009, Lleras-Muney 2018).

Yet, the mechanisms underlying these associations are poorly understood. Several proposed explanations suggest that individuals growing up in poor households make fewer investments into their health throughout their lifetime, albeit we do not know why that is the case.

In a recent paper, we ask whether unequal access to informal health expertise contributes to health inequality (Chen et al. 2019). The overwhelming share of individuals’ decisions about their own health investments happens outside of the walls of the formal healthcare system. If, from a very young age, children in poorer households are exposed to less health-related expertise, and, as a result, acquire less tacit knowledge about how to invest in their health, then we would expect these children to have worse health and higher mortality as adults.

Thus, our hypothesis is that exposure to informal health expertise affects health, and, consequently, that unequal access to such expertise may perpetuate differences in health between richer and poorer households. To test this hypothesis empirically, we consider one quantifiable measure of exposure to informal health expertise: having a health professional – a medical doctor or a nurse – in the family.

For our analysis, we use rich administrative data from Sweden. These data include rich socioeconomic information, precise information about education, detailed birth records, health care records, and prescription drug records, and mappings of family trees spanning four generations.

Despite Sweden’s universal health insurance system and generous social safety net, we document pronounced inequality in mortality and morbidity. For example, out of 100 individuals that are alive at age 55, nearly 45 will have died by age 80 at the bottom of the income distribution (lowest 5%), while fewer than 25 will have died among the top 5%. We find similarly large differences in the prevalence of lifestyle-related chronic conditions at older ages, in the rate of preventive investments among adolescents, and in the rate of prenatal tobacco exposure. Hence, despite equalised formal access to healthcare and a well-developed social safety net, Sweden exhibits substantial health inequality, measured across a wide range of ages and conditions. In fact, we find that at age 75, mortality inequality is equally pronounced in Sweden as it is in the US.

These facts motivated us to examine a mechanism other than differences in health insurance or access to care that may perpetuate socioeconomic differences in health. Specifically, we ask whether a lifetime of differences in exposure to informal health expertise can account for some of the observed patterns of health inequality. Differences in the tacit knowledge of how to invest in one’s health, it seems, could persist even in an environment with universal health insurance and equal formal access to healthcare.

We start by comparing individuals who have a doctor or a nurse in the family to observationally similar individuals who do not. We find that individuals with relatives in the health profession are 10% more likely to live beyond age 80. They are also significantly less likely to have chronic lifestyle-related conditions, such as heart attacks, heart failure, and diabetes. Younger relatives within the health professional’s extended family also see gains: they are more likely to get vaccinated, have fewer hospital admissions, and have a lower prevalence of drug or alcohol addiction. In addition, the closer the relatives are to their familial medical source—either geographically or within the family tree—the more pronounced are the health benefits, according to our findings.

Naturally, we may be concerned that families with a nurse or a doctor are simply different from other families in some ways we cannot observe. These families may talk more about health, may have healthier habits, and may make larger preventive health investments, for example. In a nutshell, they may both be healthier and have a health professional in the family because of their interest in health—rather than the other way around.

To overcome this and to quantify the role of informal exposure to health expertise via a medical professional in the family, while avoiding results that would be muddled with other differences between individuals with and without a doctor in the family, we use two different empirical approaches.

First, we take advantage of the fact that in some years and for some sets of applicants, randomisation was used to break ties among equally qualified applicants to Sweden’s medical schools. This allows us to use medical school application records and compare the health of family members of applicants who won and lost such ‘lotteries’ (applicants can reapply, so we use the lottery outcome on an applicant’s first admission attempt). We find that having a relative matriculate into medicine reduces older individuals’ risk of heart attack and heart disease, raises preventive investments and adherence to cardiovascular medication, and generally improves health. All these effects are measured over a period of 6 to 8 years from the relative’s matriculation into medical school. Younger generations also benefit from having a relative get medical training: they make larger preventive investments, are more likely to get vaccinated, and have fewer hospital admissions and addiction cases.

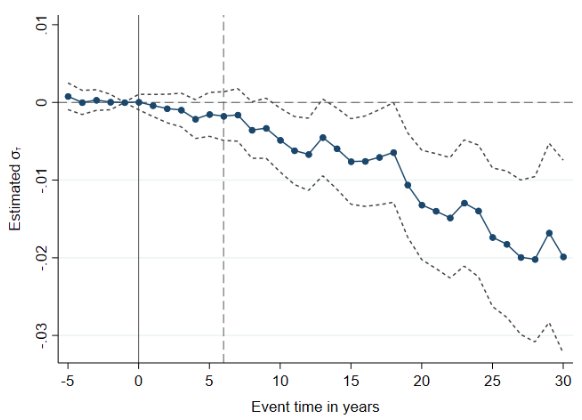

Second, we examine long-run outcomes by comparing mortality and the prevalence of chronic conditions in the extended families of individuals who train as medical doctors and lawyers, respectively. While both professions enjoy similar levels of income and social status, doctors have a higher degree of health expertise that they can transmit to their families. Comparing more than 30 years of detailed health records, we find that family members of doctors are 10% more likely to be alive than family members of lawyers 25 years after their younger family member matriculated in medical or law studies (see Figure 1). The relatives of doctors also faced lower prospects of lifestyle-related chronic diseases.

Figure 1 Doctor in the family and long-run mortality: Event study

Notes: The figure illustrates the impact of having a family member trained as a physician (relative to having a family member trained as a lawyer) on the probability of death, along with 95% confidence intervals. The regressions are centred at event year -1, i.e. 1 year before the year of matriculation in a medical (or legal) degree. The dashed vertical line marks the average graduation time for physicians. Standard errors are clustered at the family level. The estimates reveal a clear slowdown in the relative mortality rate among relatives of doctors (as compared to the relatives of lawyers) that starts emerging around year 8 after the young relative matriculates into college. The mortality gap then steadily widens for two decades. The point estimates suggest a 1.7-percentage-point decrease in the probability of death by event time 25, which corresponds to a 10% decline off the mean among relatives of lawyers, which is 17%. The sample includes family members born in Sweden between 1936 and 1940. We exclude family members who are themselves a health professional or have a health professional spouse.

An explanation that is commonly discussed in policy circles for the existence and persistence of a negative correlation between socioeconomic status and health is differences in access to healthcare across the socioeconomic spectrum. Our evidence suggests that this explanation can only be one piece of the health inequality puzzle. What’s more, our results imply that a scarcity of access to expertise in households at the lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder can create and sustain inequality in health outcomes—even in an environment with fully equalised access to formal healthcare, generous social insurance programs, and a wide social safety net.

It is encouraging, however, that the benefits accruing to medical professionals’ family members appear to be scalable. Our analysis suggests that access to expertise improves health not through preferential treatment, but rather through intra-family transmission of ‘low-tech’ (and hence, cheap) determinants of health, likely ranging from the sharing of nuanced knowledge about healthy behaviours to reminders about adherence to chronic medication, and to frequent and trustful communication about existing health. This implies that public health policies, as well as carefully designed public and private health insurance contracts that successfully mimic intra-family transmission of health-related expertise, would have the potential to close a significant share—our estimates suggest as much as 18%—of the income-mortality gap.

See original post for references

“individuals growing up in poor households make fewer investments into their health throughout their lifetime, albeit we do not know why that is the case.”

Wow, you need to get out more.

Clearly never had to choose between a medical appointment (or childcare?) and losing a job, or organic food vs electric bill or whether to spend last $20 on booze or crack than a fancy vacation, because ya know, choices.

I suspect while most swedes can walk into a doctors office or pharmacy without fear of instant bankruptcy, there remain abundant opportunities for wealth and social inequality to exact a heavy toll on low-income peoples health.

Pundits strain so hard to evade the conclusion that poverty itself is the cause of health inequality–from access to opportunity to networks and knowledge and simple TIME–I’m surprised they don’t all have hernias.

Maybe they just live in remote rural hamlets or decrepit mining towns or hydro-power plants or “especially vulnerable areas” in isolated, crime-ridden suburbs where Europeans have been hiding their immigrants and poors for many years.

Or, see Stockholm homeless tent cities here: https://www.humankind.city/2014/02/a-stockholm-slum/

“How can they live this wayyy? said the Park Avenue Dowager gazing down at the smoky hovels under the Third Ave el.

Yesterdays New Republic link, “The Gross Inequality of Death in America” actually DOES explain why health care “access” is only a small factor in life expectancy, and lifestyle “choices” (smoking, drinking) are also less important than the smart-asses would have us think.

It seems a lifetime of chronic stress, lack of agency, social isolation and yes, inequality itself are the biggest drivers of adverse health outcomes.

I suspect most 10-year olds in our nations most depressed rural hamlets and urban ghettos know this, but by all means bring on the academic studies.

https://newrepublic.com/article/153870/inequality-death-america-life-expectancy-gap

You are too busy being triggered and are ignoring the finding of the study, which found that low income people who had relatives who were in the medical business have markedly better health outcomes than one that don’t:

You are too busy being triggered…

I was pointing out the chronic myopia privileged people have in discussing, or researching, the behavior of the poors, as evidenced by the quote.

The Health Inequality Project found “the majority of the health-wealth gap? “the psychosocial impact of being poor.” About +50%

And that …”about one-third of the health-wealth gap can be explained by “risk” factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and reliance on fast food.” So, 33%

Being related to a doctor is another non-healthcare access cause of health disparity. 10%.

So, neither health care access, lifestyle behaviors or MD siblings are the primary drivers in health disparity. Poverty is.

Of them all, having relatives in medicine is probably the least amenable to improvement. I should talk to my brother about it though.

Yves, I did not see anything in the article that says the findings relate to low income people. The article says the study looks at outcomes in the extended families of doctors and lawyers and says they specifically studied doctors and lawyers because they have similar socio-economic status.

Indeed,it also makes an undefined claim (and unsupported by the excerpts in the article) that “the benefits accruing to medical professionals’ family members appear to be scalable” and that “access to expertise improves health not through preferential treatment, but rather through intra-family transmission of ‘low-tech’ (and hence, cheap) determinants of health, likely ranging from the sharing of nuanced knowledge about healthy behaviours to reminders about adherence to chronic medication, and to frequent and trustful communication about existing health.”

To me, this sounds like wishful thinking, that if everybody had better information, listening doctors etc. we could improve healthcare. Whereas the truth of it is that decent healthcare is rationed under every system of provision and people with forceful and effective advocates get better care (and depending on the system, insiders can pull strings) – and for me the only fix is to spend more on the power and increase their rations of healthcare.

I suggest you read the first two sentences:

“May.”

But they didn’t actually study the effects on the Poors. Probably couldn’t find a sufficient sample of Poors with MDS in the family.

What is certain is that they compared doctor families 2 lawyer families.

It’s interesting in its way, but presents limited opportunities to scale up.

Not really surprising that connected people get more nice things.

As a 2nd generation Swede (and one of 9 kids!) with relatives still living there, I find this study fascinating. My cousin and her daughter are pharmacists and they surely have helped increase their family’s odds for longevity.

Most of my siblings graduated from college (at a time when huge debt didn’t accompany higher education), but I am the only one who went beyond college to graduate school to become a doctor. I left my career as an internist and endocrinologist early, disgusted by how big business had overtaken the profession. That said, my immediate family benefits from my advice. I can mitigate unnecessary testing and unproven/costly treatments.

As for my own health, I do all I can to stay away from the system–or lack thereof.

Anecdotally, I’ve no doubt that Yves is correct – the primary determinant is likely to be better treatment in hospitals, more than access to information.

I’m fortunate to have a senior and well known academic medical professional in my broader family, as well as several other doctors, nurses and social workers. It is certainly very useful to have someone to call for minor queries, or to just ask ‘my doctor says should take X, what do you think?’ But by far the biggest advantage is the reaction of doctors when you namedrop a senior medical professional, or have him make a casual call as a follow up. When my parents were in decline we definitely got additional attention from senior medical staff as a sort of professional courtesy as soon they realised the family connection. While in theory this shouldn’t mean significantly better outcomes, I’ve no doubt the impact is cumulative over time for someone needing specific attention and lots of treatment.

It can help medical professionals as well. I’ve a relative in NY who recovered from a very serious cancer, she’s a very experienced teaching nurse. She was quite open about how knowing so many senior oncologists personally gave her a huge advantage in making sure she got precisely the right treatment – again, it was a matter of professional courtesy.

I agree. I think knowing, and being known within the healthcare system makes a difference. I’m not a medical professional, and have none in my family, but I’ve worked in academic medical centers throughout my career. When my 80+ year old father decided to move to my area, I could email a doctor I worked with and ask her which primary care doctors she would recommend. I could email an excellent pulmonologist that I worked with and as him if he would see my dad. I could ask my aging athlete buddies who have had hip and knee replacements about their orthopedists. My dad is receiving far better care now than he was previously. His last pulmonologist told him he had COPD and prescribed very expensive medication. His new one, who spent over an hour with my dad on his first visit, concluded that he didn’t have COPD. Not only is my dad not taking medications he doesn’t need, he also isn’t living with the specter of a progressive, debilitating illness.

Meanwhile, I have an aunt in New Haven who has had colon cancer, thyroid cancer and is really struggling to get the care that she needs. I’ve watched other family members struggle to navigate their health care systems as they dealt with acute or chronic health care issues. Being “inside” the system, or knowing someone who is, makes a big difference.

“Medical professionals take other medical professionals far more seriously than laypeople”

This is endemic in any number of environments.

Police officers have much higher regard for other police officers, tolerate civilians employed by the police, and have major reservations about other civilians.

Accountants pay attention to other accountants. I once worked for a major division of a major corporation. Our work had nothing to do with accounting, but the Senior VP in charge of the division was an accountant. If we wanted approval for a project, we explained it to the division’s head accountant until he knew what to say, and sent him to the SVP. It was the only way to establish ‘credibility’ in the SVP’s eyes.

Libraries are run by librarians, who consider librarians to be the only true professionals. Doctors, lawyers, engineers, architects? Nope, unless they also have a library degree.

All of the above validated by personal observation.

I understand from a friend who was an officer in the US Air Force that graduates of the US Air Force Academy only really consider other such graduates as real peers, and all other officers as less competent and important.

I’m sure it’s the same in all sorts of other circumstances, with the label for the ‘trusted and credible’ group changing as needed.

Sort of looks like an inconvenient quirk of human psychology, does it not?

We are, after all, pack animals

I’m getting a different reading as to what is stated in this article. They talk about public health policies mimicking intra-family transmission of medical expertise but maybe it is more a matter of not having central hospitals and central clinics but instead more, smaller hospital and clinics and more local neighbourhood medical access. The sort of the way they did medicine a century ago so that the doctors & nurses were actual members of the community who were on a familiar basis with their patients which ensured continuity of care. Any complicated cases would then be passed onto larger hospitals but most care would be done on a local level. It wouldn’t be on a intra-family basis but would be more consistent across communities.

A close friend who is a neurologist saved me a lot of grief when I had this neurological problem. The hospital wanted me to be seen by a nurse practitioner because of my insurance not been so great. My friend called one of the staff neurologists and argued that I needed to be seen by her and got her to agree. Their conversation lasted twenty minutes.

I asked her why did she call this particular physician and she said that she was reading the work histories of the staff members and one thing stood out about her. This doctor after serving her residency at the hospital stayed on and got a permanent position. My friend said this is rare and could only happen if she was really good. She explained that residents almost always continue their careers elsewhere once their residency is over. My point being that this is the kind of detail that few people would pick up on and yes, this doctor was fabulous.

A tip from a pal, who thinks it has worked for her as a patient in the NHS: when deciding which of her siblings to enter on a form as Next of Kin, inspiration struck and she put down the one with a doctorate. Yup, having Dr Smith as your next of kin is a good move, she believes.

Good tip.

The comparison of medical professionals/families to attorney/families is instructive. The stress factor of being an attorney, winning arguments for rich or desperate clients is pretty severe. So far medicine, the most benign of all the professional occupations, is less stressed out. But that probably will change because they are becoming part of bigger health consortiums which expect them to budget their time at the same time that they obey their duty to care. It would be interesting to do a repeat of this study even in Sweden because Sweden is getting cost conscious too. In the US, medicine has reached guild levels of self protection. Hopefully that will come to an end soon. But stress is clearly the overall problem. Whether poor or well-off. Poor people suffer far more insecurity, deprivation and general stress. Less happiness. More misery. We shouldn’t suspect too many extraneous root causes for this inequality. We should focus on stress and when we do we have to admit we have deep structural stress that sinks to the bottom and just simmers there.

Susan:

Thanks, my instincts agree that you are correct that stress–in the broadest sense–is the major driver of poor health outcomes that medical technology, universal access or behavior modification; even family connections cannot fix. Because the damage is done. And we send sick patients right back into the conditions that caused the disease. Think toxic waste dumped in poor neighborhoods.Make your own list. But there’s data!

The Health Inequality Project supports this:

“Drawing on research from neuroscience, psychology, and neurobiology, Sapolsky found a powerful link between poverty, chronic stress, and severe health outcomes. As our body’s adaptive response to external threats, short-term stress can be a good thing: It prompts the fight-or-flight response that can help us survive dangerous situations. However, human beings uniquely experience what is known as “chronic stress”: prolonged psychosocial stress that can last for months or even years.

Chronic stress can literally kill us. It increases the risk and severity of diseases like type 2 diabetes and gastrointestinal disorders, impairs the growth of children, suppresses our immune system (rendering us less able to fight even basic sicknesses), and increases our likelihood of becoming depressed or addicted.

While all humans experience stress, Sapolsky points out that the experience of chronic stress is not evenly distributed across society. An extensive biomedical literature indicates that people are more likely to experience stress-related diseases when they lack control over, and social support for dealing with, stressful conditions. The poor disproportionately face such conditions.”

https://newrepublic.com/article/153870/inequality-death-america-life-expectancy-gap

https://healthinequality.org/

Oh, having a health care professional in the family can be a life saver.

I had an uncle in need of a kidney transplant, on dialysis, over 70 – not at the head of the line for a kidney.

One day, he’s in dialysis and his daughter (a nurse) was in town while he was having the procedure.

She noticed the machine was no hooked up to him correctly.

He received a new kidney that same year.