Yves here. Randy Wray has an important post on how, contrary to the views of some pundits, Japan isn’t following MMT principles, particularly with Prime Minister Abe raising the sales tax when Japan has a negative policy interest rate.

However, and I hope people who are more current on Japan would pipe in, it’s not clear that it is all that easy to do what MMT proponents advocate, which is to stimulate consumption. Japan has been trying to do that since the mid 1980s with not much success.

Admittedly, more government net spending would improve the labor market. Even though Japan’s headline unemployment rate is 3%, that figure masks considerable under-employment and employment insecurity. As an Asahi Shimbun article in the past week points out, a significant portion of university graduates in the post-crisis years of 1993 to 2004 wound up as “freeters” or temps. Even if they worked for long periods for a large company, they were still second-class citizens, subject to reductions in hours and not integrated into the extremely important social fabric of the organization.

The Asahi Shimbun article says the government wants to Do Something:

The labor ministry compiled a package of policy measures May 29 to help people in their mid-30s to mid-40s, the so-called lost generation, land stable employment.

Millions of people in this age bracket failed to find regular work after they graduated from university or high school due to the slowdown triggered by the collapse of the asset-inflated economy in the early 1990s.

The ministry said the next three years will be an intensive support period as it expands subsidies for companies that hire those in their middle 30s to middle 40s as regular employees.

It will also implement vocational training programs in cooperation with companies or local governments….

People who graduated from university or high school from around 1993 to 2004 faced extreme difficulty landing stable jobs.

Now aged between 35 and 44, they number about 17 million in total. Of them, 3.17 million are non-regular workers and 520,000 people are “freeters,” those who continue to work as part-timers without landing regular work. About 400,000 people are not looking for work.

As a pillar of support measures, the ministry will set up vocational training courses so that trainees can obtain qualifications to secure stable jobs quickly.

Courses will be offered through industry organizations covering industries such as construction, transportation and agriculture, which are all facing a shortage of workers.

The ministry will also make it easier for companies to apply for a subsidy of up to 600,000 yen ($5,475) for offering regular work to those from the lost generation…

As a result of their unstable employment record, many of those from the lost generation have also faced difficulties getting married.

Low household formation isn’t entirely due to the lousy state of the Japanese economy. “Parasite singles,” meaning women who deferred marriage by staying with their parents and (often) having some sort of paid work started in the bubble years of the 1980s. They were arguably caught out by the crisis. However, I wonder even if the economy hadn’t imploded, how many would actually have gotten married later. These women were seldom putting off getting married to pursue careers; only in 1987 did Japan require that companies hire women into a professional track, as opposed to being “tea ladies” who were expected to get married. My impression at Sumitomo Bank then is that very few women were hired for these positions and they were hazed badly by the men.

I can’t prove it, but I would hazard that a significant driver of the drop in the household formation rate was women not wanting to get married because they didn’t like the deal. Successful men would work late all week (and even on Saturdays), often coming home drunk. They would bear all the childrearing duties as well as keeping up the household and cooking.

Another reason it is hard to get Japanese to consume more is that they live in cramped housing. I visited two homes in Japan, which is a big honor. One was of a Sumitomo Bank board member in Hiroo Garden Hills (super glam by virtue of having open space with trees and grass while being within the Otemachi line, as in central Tokyo). He had what looked like a 900 square foot apartment, with a not large combined living-dining room, a small galley kitchen, one bath, and three barely-bigger-than-tatami-mat-sized bedrooms. It had simple and not fancy furniture. And there would be no point in tarting it up, since pretty much no one entertains at home.

The other residence I saw was of a billionaire client in Nagoya. It was a proper reasonable sized house, maybe 2500 square feet with nicely proportioned rooms. It was furnished traditionally, which means hardly at all. My client did show me his vault and some of his Goyas, but that was as far as his display went. And buying Goyas does not do much to stimulate the domestic economy.

By Randy Wray. Originally published at New Economic Perspectives

In recent days the international policy-making elite has tried to distance itself from MMT, often going to hysterical extremes to dismiss the approach as crazy. No one does this better than the Japanese.

As MMT began to gather momentum, its developers began to receive a flood of calls from reporters around the world enquiring whether Japan serves as the premier example of a country that follows MMT policy recommendations.

My answer is always the same: No. Japan is the perfect case to demonstrate that all of mainstream theory and policy is wrong. And that it is the best example of a country that always chooses the anti-MMT policy response to every ill that ails the country.

Reporters find that shocking. Biggest government fiscal deficits in the developed country world? Check. Highest government debt ratios in the developed country world? Check.

Isn’t that what MMT advises? No.

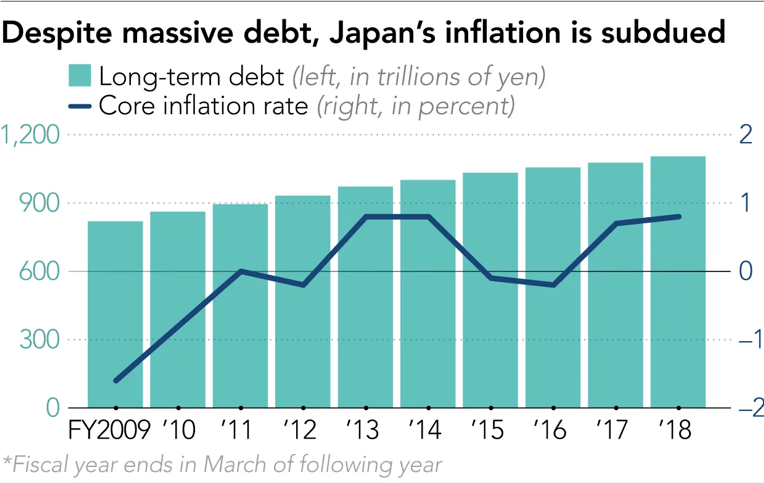

Nay, it is the perfect demonstration that all the mainstream bogeymen are false: big deficits cause inflation? No. Japan’s inflation runs just above zero. (See graph https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Growing-Modern-Monetary-Theory-debate-rattles-Japan-officials.)

Big debts cause high interest rates? No. Japan’s policy rate is about -0.10 (negative rates).

Big debts cause bond vigilante strikes? No. Japan’s government debt is hoovered up as fast as it can be issued. (All the more true with the BOJ running QE and creating a “scarcity” in spite of the quadrillions of yen debt available.)

Critics of MMT counter that Japan is “proof” that big deficits kill investment and growth.

Well, it is true that Japan has been growing at just 1% per year—certainly nothing to write home about. However, investment grows at about a 2% pace, but is pulled down by lack of consumption growth—which has averaged just about zero over the past few years.

Yet, unemployment clocks in at only 3%–in spite of slow growth—as the labor force shrinks due to an aging population. Per capita GDP has been stuck at about $38,000 for years (not so bad, but not growing). And Japan’s current account surplus has surged from under 1% to 4% of GDP over the past few years (considered to be good by most commentators).

Unfortunately Trump’s trade war seems to have already hurt Japan’s exports and the prognosis for growth this year is rather dismal. The April survey of consumer confidence showed it collapsing to the lowest level in three years. (https://www.focus-economics.com/countries/japan)

From the MMT perspective, what Japan needs is a good fiscal stimulus, albeit one that is targeted.[i] Japan has three “injections” into the economy: the fiscal deficit (which has fallen from 7% of GDP to about 5% over the past few years—still a substantial injection), the current account surplus, and private investment. But what it needs is stronger growth of domestic consumer demand—which would also stimulate investment directed to home consumption. So fiscal policy ought to be targeted to spending that would increase economic security of Japanese households to the point that they’d increase consumer spending.

So what is Prime Minister Abe’s announced plan? To raise the sales tax to squelch consumption and reduce economic growth.

You cannot make this up.

This has been Japan’s policy for a whole generation. Any time it looks like the economy might break out of its long-term stagnation, policy makers impose austerity in an attempt to reduce the fiscal deficit—and thereby throw the economy back into its permanent recession.

Clearly, this is the precise opposite to the MMT recommendation. And yet pundits proclaim Japan has been following MMT policy all these years.

Why? Because Japan has run big fiscal deficits. As if MMT’s policy goal is big government deficits and debt ratios.

No. We see the budget as a tool to pursue the public interest—things like full employment, inclusive and sustainable growth. To be sure, by many reasonable measures Japan does OK in spite of policy mistakes. Certainly in comparison to the USA, Japan looks pretty good: good and accessible healthcare, low infant mortality, long lifespans, low measured unemployment, and much less inequality and poverty. But Japan could do better if it actually did adopt the MMT view that the budgetary outcome by itself is not an important issue.

But, no, the Japanese officials are falling all over themselves to make it clear that they will never adopt MMT. Finance Minister Taro Aso called MMT “an extreme idea and dangerous as it would weaken fiscal discipline”.

One wonders how a reporter could listen to that without bursting out in laughter. Japan’s “fiscal discipline” would be threatened by MMT? The debt ratio is already approaching 250%! By conventional measures, Japan has the worst fiscal discipline the world has ever seen!

But, wait, it gets even funnier. “BOJ policy board member Yutaka Harada kept up the attack on MMT. The approach proposed by MMT will ‘cause [runaway] inflation for sure’. “ https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Growing-Modern-Monetary-Theory-debate-rattles-Japan-officials

The BOJ has done everything it could think of for the past quarter century to get the inflation rate up to 2%. Quadrillions of QE. Negative interest rates. And the BOJ thinks MMT could produce runaway inflation? I doubt that even Weimar’s Reichsbank could cause high inflation in Japan.

OK, that’s a cheap shot at Japan’s policymakers.

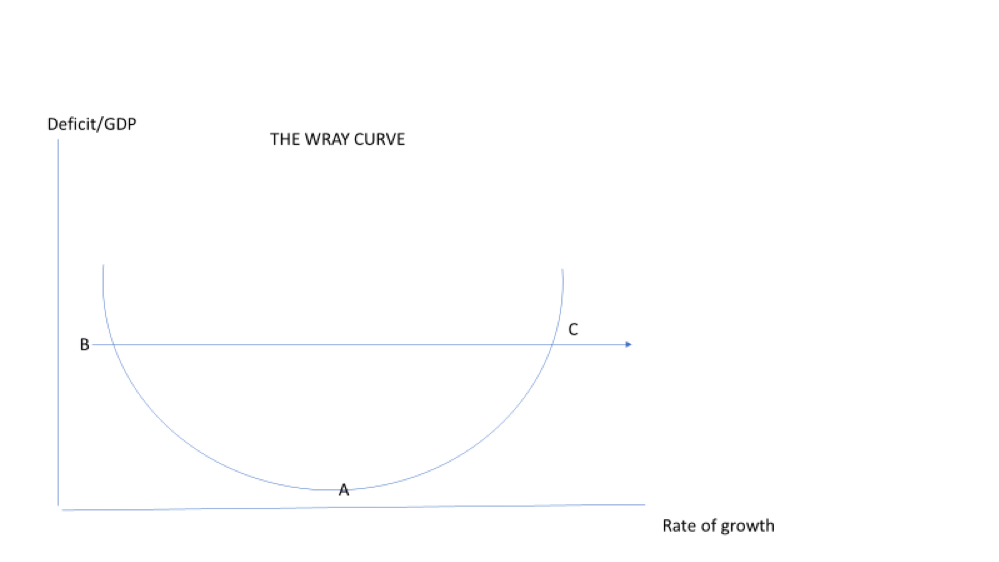

What they do not understand is that there are two ways to produce a high deficit (and debt) ratio: the ugly way and the good way. MMT has been arguing this for a long time, but with little progress in promoting understanding. I think that the main reason is because we’ve been using plain English. Economists are not good at reading for comprehension. They need pictures and math. Perhaps the following will help.

Yes, I gave it a name. There’s the Laffer Curve, the Phillips Curve, and now the Wray Curve. I didn’t draw it on a cocktail napkin at a bar, but, rather, jotted it down on a note pad before bed last night.

Assume the economy is at Point A—for Japan this would represent a 5% deficit ratio and a 1% rate of growth. Now PM Abe imposes a consumption tax, or the USA plummets into a downturn, reducing Japan’s growth rate. The economy moves up and to the left toward Point B as growth slows and the deficit ratio rises.

Slower growth reduces tax revenue even as it scares households and firms, which reduce spending in an effort to build up savings. The slower growth also reduces imports so the current account “improves” somewhat. From the sectoral balance perspective, the government’s balance moves further into deficit (to, say, a 7% fiscal deficit), the current account surplus rises (say from 4 to 5%) and the private sector’s surplus grows to 12% (the sum of the other two balances).

That’s the ugly way to increase a fiscal deficit. It is the Japanese way. It is like a perpetual bleeding of the patient in the hope that further blood loss will cure her ills.

What is the MMT alternative? Measured and targeted stimulus designed to restore confidence of firms and households. Ramp up the Social Security safety net to assure the Japanese people that they will be taken care of in their old age. Recreate a commitment to secure jobs and decent pay. Either promote births or encourage immigration to replace the declining workforce. Undertake a Green New Deal to transition to a carbon-free future.

In that case we move along the curve from Point A toward Point C. The fiscal deficit increases in the “good” way, while growth improves.

Note, however, that the boost to the deficit will only be temporary. Households and firms will begin to spend and their surplus will fall. The current account surplus will fall, too, as imports rise. Tax revenues will increase—not because rates rise but because income increases. The fiscal deficit will fall as the domestic private surpluses decline. Precisely how much the deficit will fall depends on the movement of the private surplus and current account surplus—with the deficit falling to equality with the sum.

In terms of the graph above, the Wray Curve shifts out to the right. Point A will be consistent with a higher rate of growth for a given deficit ratio. There’s nothing “natural” about the deficit ratio at Point A—as it depends on the other two sectoral balances.

For the USA, Point A is consistent with a higher growth rate but probably a similar deficit ratio to that of Japan. Our current account balance is of course negative—which implies a higher fiscal deficit. However, our private sector’s surplus is smaller than Japan’s for any given growth rate—which implies a lower fiscal deficit. The two essentially offset one another to leave the US deficit ratio at about 5% but with higher growth than Japan.

Note that we are not proposing a sort of Reverse Laffer Curve. Recall that the Laffer Curve says that tax cuts more than “pay for themselves”—trickle-down growth boosts revenue sufficiently to close a fiscal deficit. I am not arguing that the stimulative increase of government spending will increase tax revenue so much that the deficit ratio returns to its original level (or less). Where it actually ends up depends on movements of the two other sectoral balances.

Not that the size of the deficit—by itself—is important. What is important is whether government budget policy helps in the pursuit of the public and private interests. The deficit will always adjust to be “just the right size” to balance the other two sectoral balances. But that equality can be consistent with any growth rate—including a rate that is too low (deflationary) or too high (inflationary).

And the sectoral balance equality holds with any fiscal deficit ratio. So while it is likely that a successful stimulus will shift the Wray Curve out to the right, we cannot predict exactly where the new fiscal deficit ratio will settle as the growth rate rises.

What is most important about this graph is the recognition that there are (at least) two different growth rates consistent with a given deficit ratio. We can achieve a particular growth rate either in the “ugly” way or in the “good” way—while generating the same deficit ratio. Japan continually operates its economy to produce “ugly” deficits—precisely because it fears fiscal expansion.

For further discussion of fiscal deficits along these lines, see the new textbook by Mitchell, Wray and Watts, Macroeconomics (Macmillan International, Red Globe Press), Chapter 8, and especially pp. 124-128.

[1] Note: I am presuming that Japan is unhappy with zero growth, and that the country faces many unmet domestic needs. I am not an advocate of “growth for growth’s sake”—especially in light of the growing recognition that humanity may well have only a decade or so left on planet earth unless we very quickly change our ways. However, “changing our ways” will require major investments in a Japanese Green New Deal—so even with zero growth, there is a role for ramped up fiscal policy.

This article doesnt address the massive corporate debt of Japan. How will it play into this narrative? Will the gains from the stimulus be used by corporates to pay off their debts rather than investment(and hence hiring)?

First, there is no need for a company to pay off its debts if it can service them. There has been so little loan demand in Japan for years that banks lend at super low rates.

In fact, for businesses to net save, which is what you posit, is a highly abnormal state of affairs, as we explain here:

http://auroraadvisors.com/articles/Shrinking.pdf

Second, interest rates are not a primary determinant of whether a business invests, unless interest is one of the most important costs of production. That is usually the case only for financial services firms and leveraged speculators (which can include real estate players). What determines whether a business invests is whether it sees a commercial opportunity. If the cost of money is too high, that might constrain whether it goes ahead, but businesses don’t run around and, say, build new plants just because money is on sale.

Japanese businesses (on the whole) aren’t investing at home because the economy is so crappy. That is why more government spending to kick the economy out of stall would help spur more investment.

Hi Yves, I agree it could be the massive chauvinism that the Japanese jocks exhibit that’s put many ladies off any notion of marriage..that will slow a country down…..I worked with these fellers in the sugar industry. They would come to NYC to do some bidness and be entertained…no women brokers invited or any part of discussions !!

So richard koo is wrong? If i’m correct he’s positing that the corporate debt hangover after the asset bubble crash is so high that companies are scared to invest.

It’s not that simple. The issue was the failure of the Japanese banks to write off bad loans. Those were heavily with smaller companies (the big Japanese companies have a lot of mom and pop suppliers)and retailers (Japan has a fabulously inefficient retail sector, which frankly I think they sort of like). These companies were not important in terms of investment but are in terms of employment. But keeping them alive zombified the banks, which restricted credit to big companies. The banks for a very long time were only rolling bad zombie loans and not extending new credit. And now citizens have become so conditioned to a weak economy that they save even more than before.

Starting to think maybe we’ve been looking at economics all wrong. I really question why a country must grow economically EVERY YEAR? what’s so bad in a downtime for the economy? If a human body needs rest, gets ill and must relax, then why not an economy? I mean it really is just a sum of human activities within a specified geographical area. Anyways these are just some of my recent thoughts.

There’s no inherent reason, of course. There are some relationships that make that a common occurrence.

If your population is increasing, all other things being equal both the money supply and GDP should increase too. MV=PQ. If you try to hold the money supply constant, then more people buying more stuff forces velocity of money to increase (hard) or prices to go down (deflation SUCKS!). Increasing the money supply so that everyone’s budget runs on autopilot is sane.

For several decades, there have been very few countries with a sustained, falling population dynamic. There haven’t been all that many who choose deflation as a matter of course.

Japan helped Adair Turner realise why we will need MMT.

Most economies have made the same mistake Japan made in the 1980s.

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

The sequence of events:

1) Debt fuelled boom

2) Minsky moment

3) Balance sheet recession

We were using an economics that didn’t consider debt, so no one realised what was happening.

Adair Turner has built on Japan’s experience to come up with a better solution than that used by the Japanese.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

In Japan, the “private debt” component was going down as they deleveraged from their 1980s debt fuelled boom and they had to increase the “public debt” component to maintain the Japanese money supply.

Richard Koo explains (he’s had thirty years to study the balance sheet recession in Japan):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Everyone is like Japan, but the Japanese have already found that a private debt problem becomes a public debt problem using their solution.

There is a way to get the overall debt down.

Adair Turner explains:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCX3qPq0JDA

It’s Government created money, MMT.

Just to underline your point that “We were using an economics that didn’t consider debt”…which is what MMT and Minsky do… It’s hard to detect something when it’s concealed so completely that it doesn’t show up in the economists’ calculations.

I’d add that neoclassical economics also “disappears” land as an element of production (so capital now includes land because there’s no fundamental difference between manufacturing machinery and the ground on which it sits).

Unsurprisingly the crisis at the intersection of real estate and debt — the subprime mortgage meltdown — did not appear in neoclassical economists’ calculations.

If anyone in the mainstream was looking at private debt they would have seen 2008 coming.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

Steve Keen looked here and saw it coming in 2005.

Richard Koos conveniently ignores the fact that 0% interest rates were not available to the consumer who were still charged quite high rates. No wonder the people refused to borrow in a recession. And I wonder if the 1996 “recovery” was solely do to Reagan’s structural adjustments.

As correctly noted, Japan doesn’t quite implement MMT as there’s some important aspects of both fiscal and monetary policy which preclude any direct comparison with what would be seen as “classic” MMT theory. That said, it probably comes closer than any other country to an MMT-lite approach, so it is worthy of study.

Again, as stated, Japan is a useful Petri Dish into the limitations of what MMT could, even if pursued to its fullest conclusions, achieve. MMT can do nothing for the stock of social capital. It cannot do anything about a legal system. It is unable to shift cultural norms. These factors weigh heavily on Japan.

It’s probably too limited a space here as a comment to do justice to the complexity of even one of these elements as they apply to Japan, but at the risk of being glib, I’ll take on a couple of the most noteworthy ones.

Firstly, yes, since about 1985-ish, Japanese women simply reneged on the classic “deal” they’d been presented with primarily since the end of the war but even beyond that. Namely, women in Japan stayed at home while, if married (and marriage was an essential contractual buy-in to this) to salaryman got to do nothing more than raise the children, keep house and, if not limited to just shopping, then merely undertake socially-acceptable pastimes such as calligraphy or ikebana. A few might do some sort of community volunteer work, but paid, high status or highly responsible employment was simply out of the question. It was a pleasant enough existence but often a lonely one and not particularly fulfilling. Even in traditional jobs which in the west women dominated such as teaching or nursing, women were marginalized — any managerial decisions were taken by men, often fairly cluelessly as they didn’t operate at the front line. In earnest, from the 1990’s, enough was enough.

This might have been amenable to damage limitation but then, at the same time, at — primarily — US insistence and based on US-originating theories, Japan’s conglomerates were urged to focus more on “shareholder value”. This was the death-knell of the salaryman as the mainstay of Japanese industrial norms. The salaryman still existed, of course, but in fewer and fewer numbers. Rather than go into a competition with other women to secure their place as a salaryman’s wife, a great many Japanese women simply came to the conclusion this was not really a competition worth winning.

Household formation sank and with it the birthrate.

What’s often missed, however, is that even if Japanese society had been prepared to offer women equality with men in the workplace, there simply wasn’t the groundswell from women seeking to become “salarywomen”. As a way to live your life, this isn’t an especially attractive one — lots of busywork, lots of compulsory socializing with not-always especially nice people, lots of after-hours demands on your time. Few women were willing to consider it. And even for men, for a generation who’d been brought up in such households (where you rarely saw your father, there were few opportunities or even much of a wish for paternal involvement in bringing up junior), there was an increasing unwillingness to rinse and repeat that way of life.

Thus the trend for “freeters” (casually employed) had both a “push” (from business) and a “pull” from women certainly and not infrequently men, too.

MMT — and ignoring for a moment how fully or partially Japan executes it as a policy — was never, ever, going to be able to remedy this private sector and social sea-change.

But what about government spending and state-operated enterprises? Couldn’t they pick up the baton? Only up to a point. Infrastructure works had already been a huge absorb-er of capital formation in Japan in the 1980’s and this accelerated as private enterprise retreated in the 1990’s post-bubble economy slump. Much of this was useful — management of water courses prevented catastrophic river flooding which was endemic in Japan’s coastal conurbations (mountainous backdrops are “flashy catchments” which can attract huge rainfall totals in the rainy season, but with nowhere for all that rainfall to go, it swells rivers to hundreds of times their normal flow and, if concrete banks and river basins are not built, these inevitably break their natural banks inundate anything surrounding them). High speed rail linked major cities efficiently. Nuclear power freed Japan from external energy dependence.

But what happens, as it inescapably did in Japan, when all the projects which had any kind of economic viability — even when this was stretched to the limit by including “social” returns in their business cases — had been built out? You can continue to build bridges and shinkansen lines to nowhere, but the ongoing maintenance costs of these then act as a drag on newer business and other economic activities which might actually generate a real return. I vividly remember travelling on the high speed rail line between Osaka and Tokyo in the early 2000’s in one of the “Green Cars” (first class) — I was the only passenger in the rail-car for the entire journey. Another similar trip in the same situation and there was one other businessman. There was a stewardess to serve refreshments at your seat, let’s just say here costs were hardly covered by what I bought.

And the wear and tear plus routine maintenance on the rail-car would have — just for that journey — run at another huge loss. It was blatant economic madness — too many trains, which were too long, offering too high a frequency service for what the route could sustain. Add in track maintenance and replacement, running costs (a shinkansen train draws 20MW of electricity, you’re doing well to procure electricity in bulk at $50 per MWh, so the thing is burning c. $1000 an hour in energy costs alone) and cost of capital and while MMT means you’ve “always got the money to pay for it”, if it’s not got a reasonably high level of ridership it is an inescapable misapplication of resources.

But what else was there for Japan’s government to spend its money on? Healthcare is already well provided for. The education system is comprehensive and achieves good academic results, even if a philosophy of “teaching to test” still doesn’t produce especially notable real-life skills — again, nothing in MMT can influence how things like education are provided and what the outcomes of it should be (or not be).

In short, then, MMT might be a part of any solution to the problems which bedevil us. But it’s not a miracle cure-all. It needs to be applied in collaboration with social reform. In some ways, the MMT is the easy bit. The societal changes are the hard bit. It’s not even clear what, exactly, these should or could be. Let alone how they might be brought about. And note the passivity I’ve had to use there — “brought about”. What do our societies want to be become? If there’s no broad agreement on that, we can’t even start down that road.

Thank you for this very interesting comment. You do know a think or two about Japan! That being said, I don’t think MMTers have ever claimed that their theory explains how to encourage women to get married and have 4 children. What they do say is that a tax hike would be stupid at this time.

Thank you Clive. Really interesting insight. The high-speed macho trains are the perfect metaphor. Does make me wonder about the rise and fall of empires. They fall because nobody wants to play anymore. Your term, “state operated enterprises” was interesting too. Contrasted to state owned enterprises, it has some give. And achieves the same goals. Point being that screaming MMT is socialism is an empty reaction. All spending is socialism – the question is socialism for whom? To watch NHK you don’t sense there is trouble on the horizon.

Ah, there’s truths, there’s half-truths and then there’s NHK!

It’s far better an insight into Japan than anything you’ll see from western outlets (you often wonder if Japan has fallen into the Pacific Ocean, so infrequently do you get to hear anything about it) but it’s very much Japan’s idea of what they think gaijin think Japan should be like. Everything’s all cherry blossoms and kawaii. Once in a while, something a little subversive does sneak through, so it is worth persevering with.

Very interesting commentary Clive, thanks.

Japan of the late 80’s and early 90’s intrigued me in that it was pretty much entirely a cash and carry economy, as in folding money.

Fascinating description of a place I will never get to, Clive, so thanks for that. Your observations support the idea that MMT provides policy space — what a nation chooses to do with that policy space is a political decision, not an economic one.

Which I believe is part of the importance of understanding the basic premises of MMT — it falsifies the tiresome “how are you going to pay for it?” narrative, and exposes the “TINA” dodge for exactly what it is: an abdication of responsibility on the part of elected representatives to make those political decisions.

I thought working women were called “Officelady” rather than “Salarwomen”

To be honest, I don’t much pay attention to the economic wonkery, largely because I believe that economists tend to bend and twist reality to fit into their economic models, to the point where the theory is meaningless. Also, because I believe that economics is one part science and one part art, after all economies are comprised of people dealing with people.

That said, having lived in the U.S., and currently living in Japan, as well as extensively travelling the world due to work, I can tell you, from my unprofessional point of view, Japanese people seem way better off in nearly every category compared to the U.S. and most places around the world.

What I observe on a daily basis in Japan are extremely well adjusted and happy children. I see people driving new cars and wearing nice things. I see no crime, or almost no crime, and extreme cleanliness. I see ladies hanging out at cafes during lunch enjoying coffee and cakes with no care in the world. Some of my office lady colleagues openly admit that they want to get married so they don’t have to work any longer. That’s been my experience, which maybe is misinformed or bias.

Additionally, don’t get me started with the universal healthcare system and access to quality education. The West with all of its fancy economic models, developed largely by Westerners with a Western mindset, cannot and will not ever fully understand or explain Japan. While I myself do not fully understand the Japanese mindset, I have some hints. The language for one, due to its structure and vocabulary causes people to think in certain ways that cannot easily be explained to Westerners. Anyway, I could go on, but perhaps I’ve said enough. One more thing, with respect to Japan’s low birthrate, this a trend I believe is an indication of the per capital wealth which Japanese enjoy. I know many people who are either single, or married with no children, largely because they enjoy their weekend and/or hobbies and they view kids as a burden. And when you think about it, when one is poor, making babies, and raising kids, sure keeps one busy. By no means is Japan perfect, but comparatively speaking, I believe much better. In our new reality, with diminishing resources and environmental concerns, Economist would be wise to trash their antiquated theories and rethink reality. Maybe in the end the Bhutanese, with their economic model of Gross National Happiness, is more appropriate.

“In some ways, the MMT is the easy bit”

Thanks for the great and incisive comment Clive. I always look forward to reading all your comments when I see them.

I’m on the MMT train from an accounting and deficits and how money is created perspective, but also think the implementation/policy monitoring aspect is the more difficult thing. And then there is the bigger problem of expecting exponential economic GDP growth year on year in a finite world which MMT doesn’t address. But that is a whole ‘nother question.

Also good that Wray wrote the article describing how Japan, while showing that debt and deficits don’t necessarily create inflation as people think, also isn’t a true MMT policy implementation example

No mention of Karōshi?

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39981997

The people in Japan might have better lives if they worked less. Longer vacations, longer paid parental leave, if overtime then high cost for the employer etc. Sharing out the work so that the insecure employments instead became somewhat more secure might do some good.

It’s not the security or insecurity of employment per se that causes death by being overworked. It’s the nature of employment itself as exhibited within the perceptions of what “hard work” or “doing a good job” constitutes. It’s not just low paid and causal workers who work excessive hours, even well paid salarymen are still expected to put in long hours in the office then spend a full evening on corporate socialising at least once a week and often a lot more than that. It’s not poverty which is driving them to do this. It is a desire to be seen to fit in.

And there’s also a subtext to the whole death through overwork dynamic which is, 過労自殺 [かろうじさつ] (karoujisatsu) which is committing suicide under the guise of being overworked. Suicide ideation is more acceptable to Japanese as a culture but portraying it, at least to oneself, as a form of unavoidable and necessary self-sacrifice might serve to differentiate this form of suicide as opposed to, say throwing yourself in front of a train. Clearly, where suicide is a motivational factor, there’s a whole lot more going on than just an overbearing boss or money worries (although these, overlapping but not necessarily neatly, may also be contributing elements).

But trying to unpick all this is very hard when the subject is looked at in aggregate, but reducing it to individual cases is merely oversimplification into anecdotes.

Thanks for this article – I’ve never quite been able to get my head around the contradictions in Japans macroeconomic approach, in particular the weird obsession with raising VAT as soon as the economy shows any signs of life.

The Japanese do love some consumerism – I once met a marketing woman for LV in Kyoto – I casually asked her how hard her job was and she said ‘selling Louis Vitton bags to Japanese women is the easiest job in the world’. But from anecdote I would say the Japanese have a very different approach to consumerism than in the west or from what I’ve observed in China or elsewhere. They like their kawaii tat, but will spend little real money on it (as Yves has observed, they simply don’t have room for it). They will spend big on one or two luxury items (such as a designer handbag or swish golf clubs), but won’t overdo it. They spend a lot on good food. But little on furniture or even on cars – you don’t see as many luxury cars on the roads of Japan as you would in other more obviously poorer countries.

They also (in my experience) have a strong toleration for what others would consider unbearable or humiliating conditions. I’ve met Japanese girls working and studying in Ireland who live on very little money, often quite literally bed sharing (I know one small house with no fewer than 15 Japanese girls sharing it). They are entirely cheerful about this, seeing any other arrangement as just a waste of valuable money that could be spent on trips to Paris or beer.

So this is certainly one explanation for why successive Japanese governments have felt force to waste countless billions of yen in wasteful infrastructure spending (think of entire mountains pinned in concrete to prevent one or two rocks falling on some minor road), while being apparently unable to build half decent housing. As Clive observes above, the issues are deeply cultural.

Incidentally, for anyone wanting a wander around the backyards of weird Japanese infrastructural spending, I’d recommend the no-defunct but wonderful Spike Japan blog.

Your story about the 15 young female migrant workers sharing a small house made me think of this story:

https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/mystery-landlord-of-houses-where-up-to-120-people-were-evicted-revealed-as-notice-to-quit-served-on-activists-37215847.html

Agree with the room sharing part. It seems to be a chinese thing too.

Yep, the landlords letting out houses to people who do not know their rights are just following the cultural norm of the tenants and helping the tenants to save money… Another example here of a helpful Dublin landlord:

https://www.independent.ie/business/personal-finance/property-mortgages/secret-cameras-hidden-bunkbeds-windowless-rooms-exposing-dublin-landlord-christian-carter-36793171.html

Luckily the Irish government is doing something….

https://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/views/ourview/the-housing-crisis-mr-murphys-co-living-nightmare-926101.html

Should we import other standards as well into the EU? Why stop at housing standards, lets go for importing the environmental standards as well. We need to be able to compete, right?

Japanese companies have dorms for young men. I gather they resemble Army barracks. I know they still exist because a gaijin hired into one of the successful Japanese auto parts suppliers stayed in a dorm for his first year (the Japanese are also big on hazing gaijin before they relent and give them gaijin breaks). So this was part of the salaryman routine and reinforces that sort of spare living as a cultural norm.

No wonder the birthrate is so low; kind of hard to date when you’re living in a barracks.

Just one other point raised here by Yves on the very low Japanese birthrate and women attitude to work there. Solely based on very small sample size and anecdote I would say that Japanese women certainly reject the home based lifestyle of their mothers – but also (contrary to the western advice of ‘you need equality in the workplace with men’), they also look at the way their salaryman fathers worked and say ‘F- that, there is no way I want equality with that’.

In fact, the more casual working of the post crisis world in many ways suited a lot of Japanese women – many of whom would work temping for a while, then simply go travel or party or do what they wanted. Thats not ideal, not least because of a long term lack of security and low wages, but for many younger women it was better than sitting at home with a baby or working 80 hour weeks in often abusive environments. The problem is, I don’t think anyone prominent is really articulating clearly what they do want – or if they are, its not been listened to by politicians.

It would help to put Japan’s approach since the 80’s into the longer historical context. Japan followed Shimomuran economics, which used MMT to fund industrial investment and wrote the balancing item down in the BOJ accounts as ‘the people’s savings’ or ‘the people’s equity’

Wray’s and Yves’s points are well-taken, but i think we’re missing the importance of Japan’s apparent love/hate relationship with neoliberalism and MMT.

Japan is simultaneously making a mockery of neoliberal ideas by adhering to them with near-reliousy zealotry. Unintentionally, of course, it’s providing screaming evidence that a sovereign currency issuer has a TON of latitude on the policy front…one of the main points of MMT.

The analogy that pops into my head is that Japan is furiously trying to prove the earth is flat, and has set sail to prove its case by desperately trying to find the edge of the earth and sail off it to prove the point. But, in doing so, japan has proved the EXACT OPPOSITE is true, doing repeated loops around the planet, screaming that it will find that edge soon, no matter how many times it circumnavigates the globe.

Another analogy that pops into my head is the old skit from Dave Chappelle, about the blind, black leader of the KKK who doesn’t know he’s black.

You really just can’t argue with unintentional self-parody. It’s quite clear for all who wish to see it.

Yes, but missing so many points.

The bottom line is that Japan now has a roughly stable population. The economy does not need to grow! Even 1% growth/year is better than the United States with 3%/year, and India with 10%/year! (It’s not enough for the economy to grow faster than the population: the need for escalating infrastructure spending as population densities increases means that maintaining the status quo requires that the economy has to grow faster than the population. I mean, suppose you have one family living in a house that’s been paid off. Now you add another family: you have doubled the costs for electricity and food etc., but you have added entirely new costs for the construction of the new house. And if you now have to switch both houses from septic tanks to centralized sewer systems, at least in the medium run the costs more than double).

Most increases in ‘consumption’ in the United States are driven by increasing the size of the population. That benefits banks and large businesses, but need not benefit the average individual.

The problem is that the Japanese banks are no longer really needed, at least not in their current form, but they keep trying to force the old debt-driven growth model on an economy that doesn’t need it.

As an island nation, Japan is very aware of securing natural resources. I’m sure that’s 90% of their mindset. They trade out of necessity in some instances. And their domestic stimulus programs get ahead of themselves. Don’t everyone’s? Factoid (can’t cite) – around 10,000 bc the Japanese were well on their way to denuding their island paradise. They were big into pottery manufacturing in the southern end of the archipelago and used up all the forests vitrifying their wares. In all these millennia they have not lost their instinct for ceramic artistry. They are still the best. But they switched, at some point, from using scarce wood to using paper for their houses. I saw one in Hanover at the World’s Fair. It was very impressive. Tightly rolled paper to form strong structural logs and beams, thinner walls, etc. I forget how they waterproofed it all. Ingenious.

I think the Wray Curve is classic. Classic Wray. It’s a gyroscope. Maybe a bowl of water. Asahi Shimbun’s comment (Yves’ intro) about the “slowdown triggered by the collapse of the asset-inflated economy” is the perennial mindset in human economics – we all instinctively think those assets are valuable. When they crash we jump out of a window. And/or impose ubiquitous austerity. The EU as well. So here is Randy Wray to tell us to take it easy. It’s only a budget and we can do whatever we want with it. Thank you Prof. Wray. We have an unprecedented opportunity, globally, to use money in a good way. To mitigate climate change and improve the environment and society. This can be our mantra for centuries to come. The need for it will endure long after all our other delusions have dissipated because this time it’s actually very important to manage human society and mobilize it for the long haul. Even Liz Warren is now saying very smart things – I thought she’d never find her courage. But she is saying (my take) we need to get rid of the Fed and its schemes to mitigate the “collapse of the asset-inflated economy” which are inadequate for the problems we face – get rid of the Fed and manage our money/spending directly in the interest of society and the environment. What a novel idea. She thinks if she calls it some new” direct money management” of targeted fiscal spending that nobody will notice it is MMT? But whatever gets this new ideology over the finish line is OK with me. Go Liz.

I knew a fellow that had department stores in Guam & Tinian in the 80’s and 90’s, and he told me that he really appreciated the idea that a lass from Tokyo wouldn’t just buy one $45 item, no-she wanted 23 of the identical item to give as gifts back home.

A retailers dream customer…

So appreciate the article and readers’ comments, esp. by Clive and Susan the Other, above.

Ironic that Japan is being held up as a failed model of MMT policies. As Randy Wray notes in his opening sentence, the hysteria of establishment economists is palpable as they are beginning to be held accountable for the massive policy errors under neoliberalism, financialization, privatization, and austerity that have had such adverse consequences for so many.

Q: “Cui bono”?… Who benefits from labor desperation, suppression of domestic demand, and negative interest rates on (Yen) debt?

A: The usual suspects, including the primary dealers. Nice carry trade you’ve got going there… These are the same institutions as in the U.S., UK and EU, and that have also enjoyed negative interest rates as their cost of funds from Draghi’s European Central Bank and previously negative real interest rates under the Fed’s QE programs.

Q: Who is penalized under these policies?…

A: The Japanese people, as reflected in a low birth rate attributable to lack of family formation and negative economic considerations, and the many who have become discouraged and are no longer even seeking employment.

Q: Going forward, what are the expected effects of U.S. tariffs, both on Japan and other countries, including on the U.S. itself? Are tariffs not a hidden regressive tax that will reduce U.S. consumer demand in a way similar to the pernicious effects of the sales taxes imposed by the Abe administration in Japan? Are the economic effects of U.S. tariffs on Japan’s exports-dominated business model, both WRT direct Japanese exports to the U.S. and the secondary effects from reduced Chinese demand, negative?

GDP=Government Spending + Non-government spending + Net Exports

Therefore, GDP is government Spending driven.

But some spending is more productive than other spending, so spending on what?

Here are some suggestions, made for the US, but generally applicable for all Monetarily Sovereign nations:

Ten Steps To Prosperity:

1. Eliminate FICA

2. 100% Federally funded Medicare — parts a, b & d, plus long-term care — for everyone

3. Provide a monthly economic bonus to every man, woman and child in America (similar to social security for all)

4. Free education (including post-grad) for everyone

5. Salary for attending school

6. Eliminate federal taxes on business

7. Increase the standard income tax deduction, annually.

8. Tax the very rich (the “.1%”) more, with higher progressive tax rates on all forms of income.

9. Federal ownership of all banks

10. Increase federal spending on the myriad initiatives that benefit America’s 99.9%

Deadly Innocent Fraudulent Misinterpretation #34: “Japan is our MMT poster child that keeps exposing the myths.”

Fact: Japan is a pure MMT case study why, from the very start of economic troubles, PEN STROKES, not more keystrokes, make much better solutions to grow an economy.

http://thenationaldebit.com/wordpress/2019/02/03/seventy-seven-deadly-innocent-fraudulent-mmt-misinterpretations-29-35/

I believe it was Richard Werner who consulted with the Japanese Government and The BOJ to do Quantitative Easing and they did the opposite of his suggestions QE for the people and debt write downs. They started after WW2 with debt completely written down or off the Banks balance sheets after using window guidance their industries were subsidised forming many cartels. Had rapid GDP growth and grew as a world exporter. The BOJ and there Treasury were at odds and the BOJ took bad advise from the BIS and the Fed which resulted in the asset inflation in stocks and RE.

Good summary of Werner’s argument. I’ve often wondered why Japan caved to the Plaza Accord and western “advice” on CB policy.

Having Capital allocate removes the troublesome political thingy some talk about.