By Nicola Gennaioli, Full Professor of Finance, Bocconi University, IGIER and CEPR, and Guido Tabellini, Professor of Economics at Bocconi University and CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU.

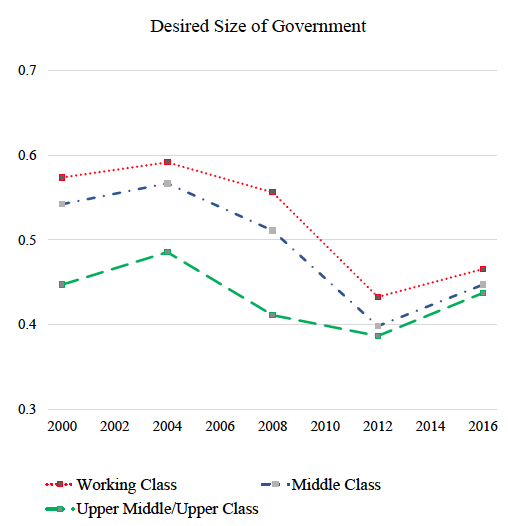

In the last few decades, the political systems of advanced democracies have witnessed momentous changes. Nationalism and populism have gained support almost everywhere, often at the expense of mainstream parties. New dimensions of conflict have emerged – over immigration, globalisation, and civil rights – in place of the classical divide over redistribution (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Changing social cleavages in the US

Note: Sample: white individuals aged 18 or over.

Some of these phenomena are correlated with economic changes. The areas of the US that are more exposed to import competition have lost manufacturing jobs and have become politically more polarised and conservative (Autor et al. 2017), and trade shocks or technology shocks account for employment losses and for the rise of populism and anti-immigration sentiment in Europe (Colantone and Stanig 2018a, 2018b, Anelli et al. 2018). Cultural conservatism and support for populist parties have been shown to be strongly correlated with economic insecurity (Guiso et al. 2017, Gidron and Hall 2017). However, the mechanisms behind these correlations are not clear. Why do losers from free trade become nationalist, dislike immigrants, and turn socially conservative? Why do they vote for policy platforms that seem to run counter to some of their interests, such as tax cuts or unsustainable budget deficits?

In a recent paper (Gennaioli and Tabellini 2018), we argue that to address these questions we need to engage with the psychology of group identity and its effect on voter beliefs. The idea that group identity and group-tainted beliefs play a key role in political change permeates the writings of social scientists and revolutionaries. According to Marx and Engels, individual workers should identify with the proletariat, viewing themselves as part of a historical class struggle rather than as carriers of specific cultural or regional traits. For nationalists like Mazzini or Herder, individuals should view themselves as part of the culture or history of an imaginary national community, downplaying more parochial differences. Lipset and Rokkan (1960) describe the evolution of Western party systems as reflecting shifting identities across salient groups such as income classes, religious versus secular groups, the centre versus the periphery, and so on. Changes in the groups of identification can explain why large economic changes can drastically change voters’ beliefs and cause them to become distorted in specific directions. It also helps explain why society becomes strongly polarised across groups, in an ‘us versus them’ conflict.

Social Identities and Distorted Beliefs

Social psychology confirms the link between identity and beliefs. According to the ‘social identity perspective’, the leading theory of groups, individuals routinely identify with social groups of similar people (Tajfel and Turner 1979, Turner et al. 1987) as a way to structure and simplify the social world. Acquiring a social identity, however, also entails an element of ‘depersonalisation’. When an individual identifies with a social group, he enhances differences between outgroups and in-groups. As a result, he stereotypes outgroups but, crucially, he also stereotypes himself by viewing himself more as a typical member of his group than as a unique personality. This implies that identification with a certain group causes voters to move their beliefs in the direction of stereotypes, increasing polarisation and conflict.

To give a political example, the stereotypical ‘cosmopolitan’ favours no controls on immigration and full European integration. Even though such an extreme position is infrequent, it sharply distinguishes the group of those who favour a more open society from the group of those who favour a less open society, say the nationalist group. When someone (say, a member of the European educated elites) identifies himself with the cosmopolitan group, he comes to view himself in contrast to a nationalist. As a result, he perceives nationalists as being more closed than they actually are, and also moves his own beliefs further in the direction of the stereotypical cosmopolitan position. Of course, the same happens when someone holding more closed views identifies with ‘nationalists’ – he thinks of himself as being in contrast to the cosmopolitans, moving his beliefs toward the stereotypical position of his group. As a consequence of this process, these voters hold certain positions not just because of the material benefits they entail, but also because of how they identify their social self.

The distortion of beliefs along group lines has been amply documented by political scientists (Flynn et al. 2017). Recent work shows that belief distortions are systematically shaped by partisanship. US voters exaggerate social mobility, but more so if they identify themselves as right-wing (Alesina et al. 2018a). Voters in the US and Europe overestimate the number of immigrants, but right-wing voters much more than those on the left (Alesina et al. 2018b). Beliefs over global warming also display large partisan differences (Kahan 2014). In our approach, distortions in factual and value judgements naturally arise due to group psychology.

To see the political consequences of this phenomenon, consider the 20th century divide of Western politics: class or economic conflict. Here, a lower-middle-class voter identifying with the working class exaggerates the benefit he draws from redistributive policies because, in thinking about the world, he focuses on the distinguishing feature of his group in contrast to the opposite group – namely, poverty or low upward mobility. The reverse happens for an upper-middle-class voter identifying with a group of rich capitalists. Beliefs about social mobility and policy evaluations become polarised, and redistributive conflict is enhanced relative to a world in which identity does not matter. The same mechanism also explains why polarisation is perceived to be greater than it actually is, in line with the evidence in Westfall et al. (2015).

Changing Social Identities

But psychology also explains why prevailing social identities may change, so that economic conflict may give room to new cleavages. Indeed, we can all potentially identify with many social groups, defined by our nation, our gender, our social class, our occupation, our cultural traits, and so on. Critically, our political beliefs are shaped by whichever identity is salient at a certain point in time, and this depends on external circumstances.

In our paper we explore the implications of this insight. We show that economic change causes new sources of conflict to become salient, in turn causing identification to change. This creates polarisation along new dimensions, while reducing it along other dimensions. For instance, a trend in globalisation clusters individual interests along exposure to foreign competition or immigration relative to, say, the traditional rich-poor divide. As a result, social identities switch from a poor versus rich conflict to a conflict between globalists and nationalists. Poor or uneducated voters exposed to the costs of immigration or globalisation de-identify with their economic class and identify with the nationalist group. This reduces their demand for redistribution and enhances their demand of external protection. These voters may benefit from greater redistribution, but they do not demand it because they now identify with a group that is more heterogeneous across income classes. Likewise, rich or educated voters benefitting from immigration or globalisation also change their identification to the cosmopolitan group. Their demand for redistribution increases and their demand for openness increases. Overall, social alliances change, individual beliefs about redistribution become less polarised, while beliefs over trade protection or immigration become more polarised. Political conflict over redistribution dampens; conflict over globalisation intensifies.

In other words, through stereotypes and belief distortions, endogenous social identities amplify certain shocks, leading to non-conventional policy responses. A shock induced by trade, or technology, or immigration can have much stronger political consequences if it changes the dimension of social identification. Critically, by inducing people to abandon class identity, these shocks can reduce the demand for redistribution despite increasing income inequality.

Amplification is further enhanced if individual traits and policy preferences are correlated across policy dimensions. Specifically, there is evidence that demand for trade protection and aversion to immigrants are positively correlated across individuals, while these traits are not much correlated with attitudes towards redistribution. This may be an effect of education, or it may be due to an underlying personality or cultural trait that varies across voters. In our theory, this correlation pattern has the following implications. When voters identify with their income class, conflict is predominantly about redistribution. Voters’ beliefs over immigration or trade policy do not polarise politics because income classes – the politically relevant identities – encompass diverse views over globalisation. But now suppose that increased import exposure redefines social identities along a new dimension associated with trade exposure (say, region of residence or occupation). Because views over trade policy are correlated with views over immigration and civil rights, this redefinition of social identities leads to correlated belief distortions over a bundle of policies. This can explain why workers exposed to import competition become anti-immigrant and demand socially conservative policies, and more generally why opinions over different policy issues are now more systematically correlated with partisan identities.

Some Evidence

The evidence supports these predictions. In a recent paper, Autor et al. (2013) show that US commuter zones that are more exposed to the rise of imports from China have become politically more polarised and conservative, and were more likely to vote for Donald Trump in the last presidential election. This could reflect a variety of mechanisms, but survey data allow us to explore more specific effects of trade shocks. Exploiting data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study between 2006 and 2016, we find that individuals more exposed to rising imports from China become more willing to accept cuts in domestic public spending, more averse to immigrants, and consider the issue of abortion to be more important. This is consistent with the idea that the trade shock induced relatively poor respondents to abandon class-based identification and switch to nationalism, given that nationalism is positively correlated with social conservatism. Colantone and Stanig (2018) find similar evidence of the effects of imports shocks in Europe.

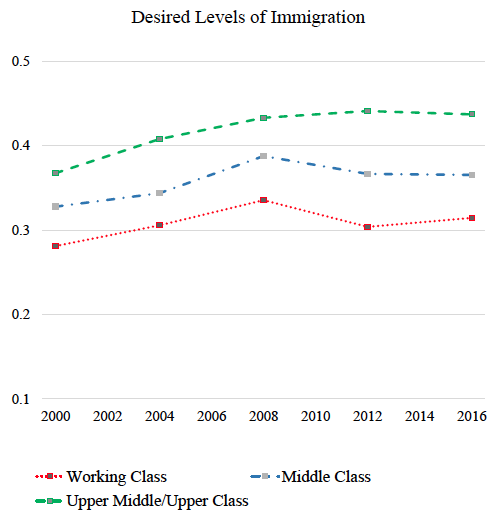

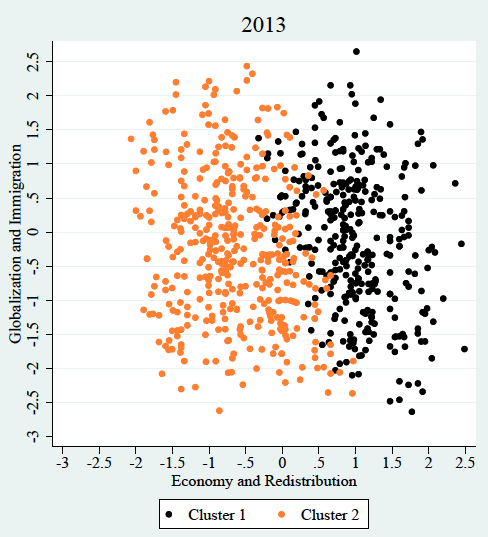

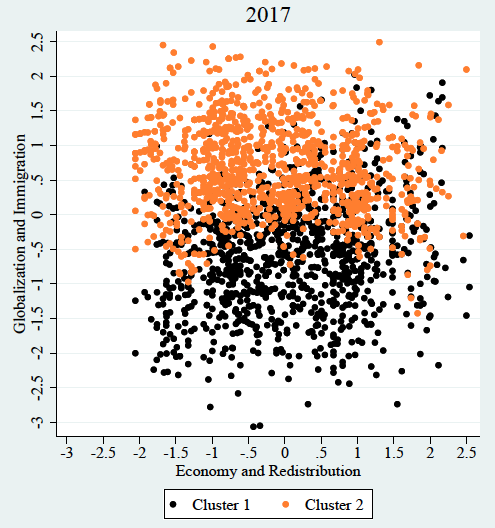

France is another interesting case study, because there was a clear shift in the dimensions of political conflicts between 2012 and 2017. This is illustrated vividly in Figure 2. The vertical axis measures attitudes towards immigration, globalisation, and European integration (higher values correspond to more open attitudes); the horizontal axis attitudes towards redistribution and the role of government in protecting workers and regulating the economy (higher values correspond to more right-wing attitudes). Each dot corresponds to an individual. The colours indicate how respondents were split between two clusters estimated from the original questions: in 2013 on the left-hand panel, in 2017 on the right-hand panel. The change in the dimension of political conflict is striking. In 2013 respondents were split between left and right, reflecting the traditional dimension of economic conflict over the role of the state in the domestic economy. In 2017, the cleavage concerned attitudes towards globalisation and immigration.

Figure 2 Changing political conflict in France

Note: Cluster analysis using Ward’s method.

In our paper we show that this change in the relevant dimension of political conflict is reflected in how people voted and, exploiting panel data, in how their policy preferences changed. Voters who, between 2012 and 2017, abandoned a left versus right identification in favour of a nationalist versus globalist identity moderated their views on redistribution, and became more extreme in their views on globalisation and immigration.

Concluding Rremarks

Trade and technology shocks are not the only source of political frictions in modern democracies. Socially conservative cultural views, which were once majoritarian, have gradually been eroded by slow-moving social changes, such as the diffusion of college education and changing gender roles. These cumulative changes created fault lines within traditional political groups defined on the left versus right dimension. Trade and technology shocks increased the relevance of these fault lines, and triggered changes in political and social identities. Socially conservative poor voters, who traditionally identified with left-wing groups despite their social conservatism, are now attracted by nationalism because it appeals to both their trade preferences and their cultural views, and vice versa for voters with opposite political features. As this happens, traditional income- or class-based conflict wanes and is replaced by new political cleavages over correlated dimensions. Political beliefs reflect these new social identities and amplify the effect of these social and economic changes.

If this view of the world is correct, the disruptive political changes that we observe in many democracies are not transitory phenomena, but represent profound and long-lasting transformations of our political systems. One important question in this respect concerns the role of the media. If exposure to social media, such as Facebook or Twitter, strengthens stereotypical thinking, it may cause the consequences of these new political and social identifications to become extreme. At the same time, identities are not biologically ingrained. Because individuals belong to several different groups at the same time, less-polarising identities are always available. As argued by Sen (2007), political platforms reminding people of these alternative identities may reduce polarisation and favour the establishment of a less conflictual political life.

To simplify: the Greco-Roman model of faux democracy, which has never worked well for the bottom half of any society, is now confronting a superior model–Confucian government, aka human authority–and losing badly.

In pre-Internet days this competition would have gone unnoticed, but now Westerners can see what a raw deal they’re getting. Next year, for example, every Chinese will have a home, a job, plenty of food, education, safe streets, health- and old age care; 500,000,000 urban Chinese will have more net worth and disposable income than the average American, their mothers and infants will be less likely to die in childbirth, their children will graduate from high school three years ahead of American kids and live longer, healthier lives and there will be more drug addicts, suicides and executions, more homeless, poor, hungry and imprisoned people in America than in China.

http://selfdeprecate.com/politics-articles/confucius-proper-role-government/

I’m sure there are lessons to be learned from Confucius, but the American political experiment (not to mention American culture) seems to be more about personal freedoms (pursuit of happiness) than the reflective self-examination of the Eastern cultures. Confucius revered tradition, and that’s not the type of political activity needed to move forward.

This definitely sounds sensible however I don’t see how the cluster analysis graphs support the conclusions. To be honest I don’t see clusters at all on these graphs and doubt that this is an appropriate technique to analyse this change. A simple two-by-two table would do just fine.

Lots to unpack here and unfortunately lots to disagree with. In the first sentence, the author talks about “the political systems of advanced democracies” which may be a misnomer. Even ex-President Jimmy Carter says that the US has become more an ‘oligarchy than a democracy’ and the same is true of a lot of ‘advanced democracies’. There was that study that came out that showed that what most Americans wanted are hardly ever taken into account by the leaders. That is not a democracy in action that but an oligarchy. Now that is a more accurate starting point.

If groups like nationalists are gaining at the expense of mainstream parties it is probably because the policies of the mainstream parties are almost identical. If neither mainstream party is no longer listening to you and ignoring your wishes, of course you are going to throw your support behind some other party. You have more to gain than to lose as it makes the mainstream parties finally take notice of you.

“Cultural conservatism and support for populist parties have been shown to be strongly correlated with economic insecurity”. Thanks for the heads-up. Would never have worked it out for myself. Look, when times get tough, people fall back into their family and their communities and have to be more careful and conservative in their choices. And they can see too that the wealthier classes that push for emigration into the country that depresses both wages and conditions never has a downside for them personally as they hardly have these emigrants as neighbours. Conservatives have shown with glee that some of the people that are most for emigration live in some of the whitest postcodes in their countries.

When the author said ‘Why do losers from free trade become nationalist’ I thought that he must have really lost the plot there. If you are going to lower the living standards of a swathe of people, make their lives more precarious and lumber them with overwhelming social conditions of degradation and decay, you had better offer them something of value in return. Because if you don’t, somebody else will.

Yes, I had a similar reaction.

Who are going to be the agents of this supposed counter-movement to “nationalism” and “populism” and what is it they are supposed to be agitating for?

If the author is proposing a return to traditional Liberal responses — which is better management of special interest groups such as the Federal Reserve, the big international companies, international finance, the EU, the military-industrial complex and the security state (to name a few of the usual suspects) — this is all well and good.

But a resurgent Liberalism is still an anathema to radicalism which states there can be no tolerance of and no hope of “reasoning” with such special interests. They are inherently opposed to any notion of government by the people, for the people. Outsourcing aspects of government to the special interest groups precludes, for the radical, the slightest possibility of those who have a franchise being able to exercise their aims in terms of economics, society, international relations, environmentalism and so on directly through their elected representatives steering the course of the government they form.

Instead, under the Liberal approach, the special interests are intended to be monitored and controlled by government — doing government’s bidding — but still allowed to hold responsibility for fulfilling the electorate’s intentions.

Liberalism can’t escape the censure that, having been given ample opportunity to try cajoling the special interest groups into doing their (and by implication, the people’s) bidding, they have not only failed to achieve that result, but worse, have so emboldened the special interest groups that government scarcely gets a look-in. The special interest groups have so embedded themselves into the fabric of statecraft, they now claim that the state(s) — national governments — simply cannot function or even exist without them.

Radicalisation, or, perhaps, better put — since we’ve undoubtedly been here before, such as in the immediate post-war period but even before that, the last decades of the 19th Century springs to mind, too — re-radicalisation seems an inevitability. The Liberal tradition can’t expect to sit there, like a tender exotic plant in the Edwardian glasshouse which has fallen into a state of disrepair, its owner unable to afford to heat it or mend the broken window panes, wondering why the sun isn’t shining on it any more.

“through stereotypes and belief distortions, endogenous social identities amplify certain shocks, leading to non-conventional policy responses. A shock induced by trade, or technology, or immigration can have much stronger political consequences if it changes the dimension of social identification. Critically, by inducing people to abandon class identity, these shocks can reduce the demand for redistribution despite increasing income inequality.”

In other words, removing class from the table enables those with power to deepen economic inequality though indentity politics. I found the above paragraph to be the most insightful part of the article.

” Critically, by inducing people to abandon class identity, these shocks can reduce the demand for redistribution despite increasing income inequality.”

that was the meat of the nut for me, too.

if you don’t tell a story, no one knows that story.

all we’ve heard for at least my lifetime is one story…to the exclusion of all others.

any attempt to tell another story is met with repression/ridicule(“socialists” in the usa) or violence(cuba, central america, on and on)

and to that point of what has become one of my greatest fears, that if the so-called-Left Party won’t tell a new story, someone surely will:

https://theweek.com/articles/845696/tucker-carlson-president

The anglo-american new left political movements don’t help themselves when they moralistically enclorthe themselves in this “open borders” civil rights discourse.any nation state has a right and duty to control it’s own borders to any degree necessary.the fact that nafta was bi-partisan isn’t going to stop republicans from pointing out that jobs and wages are impacted.i cringe at the niaevety of those on the left that csn’t get this.

It’s not clear to me how much of the left is for actual “open borders.” The left that’s at least tolerant of immigrants, sympathetic toward people already here, thinks some level of immigration brings some value, sympathizes with refugees and asylum seekers, etc., also has programs like a job guarantee, minimum wage, infrastructure/GND, expanded public services that would actually be beneficial toward workers.

The closed border right proposes to get rid of everyone “not like you” and/or not a rich oligarch, and whoever’s still here after the purge/suppression/incarceration will magically be fine. They won’t be. I cringe at the naivete of the segment of the white working class that doesn’t get this.

I think it’s more a case being against those who are against open borders, and intolerant of those who are intolerant of immigrants. The contemporary Left is largely about abuse and blind opposition, and wouldn’t be caught dead actually doing anything useful.

The basic arguments here are sound, I think, but certainly long known, as the authors themselves note in some of their references (Lipset & Rokkan; or Marx & Engels! And we could go back further). What seems to be missing is the element of elite manipulation of this basic dynamic, which has been so important in history, and certainly in US history. Divide and conquer/rule. Using race and/or ethnicity to divide the working class in the US is as old as the country itself. And as the means of cultural production and consumption have expanded and grown more complex, so have the mechanisms of elite manipulation. Though the authors do not do this overtly, I am also suspicious of any hint that such in-group biases are mainly “lower class” phenomena.

Nevertheless, it is always good to try to raise consciousness about such factors in hopes of making people more aware of them.

Very good; I plan to steal it.

The entire Civil War was illogical. To fight, you need a large army. Why would a bunch of poor white people fight for wealthy slave holders to maintain the wealthy slave holders’ wealth? Why were there millions of people willing to fight on the Southern side?

Ultimately, it had to be to maintain their sense of “home” and “tradition”, much of which was based in racism (the vast majority fighting for the South did not own slaves). The same rhetoric is being used today to effectively accomplish the same purpose.

In Europe, we saw a simultaneous large influx of formerly Soviet Eastern Europeans and Muslim refugees from Iraq and Syria into the long-established societies of Western Europe. This visible incursion at the same time as struggling economies and middle-class is at the heart of the nationalist upswing. Historically, there was strong anti-Semitism and anti-Roma in many of these areas, but those populations were small and didn’t threaten to overwhelm low birth-rate Roman Catholic or Protestant Western Europeans. Even so, they were frequently used to justify horrific actions.

So, the traditional playbook going back a long time is to mask the economic goals of the few with racism and religious intolerance for the masses.

In every case there are common elements. Immigration, technology or both used to effectively depress wages and the owners of wealth exploiting human social prejudices to deflect attention from what is really going on.

“According to Marx and Engels, individual workers should identify with the proletariat, viewing themselves as part of a historical class struggle rather than as carriers of specific cultural or regional traits.”

Marx explains how this consciousness can fail to emerge in 18 Brumaire and how the french peasantry were more like potatoes in a sack. Together but separate, they rarely engaged with their neighbors on other farms, only interacted with their family and nature…their labor value mystified by price setters for their goods in far off towns and cities.

Most suburban americans live the same way today…rarely interacting with neighbors. Only social contact outside family is co-workers in small shops or offices. They drive home alone at the end of the day and never interact outside work. They see all good things coming from the boss or company (cash, healthcare, a sense of meaning even.)

The problem with this kind of analysis is that by focusing on how people voted and what they said, it emphasises the “demand” side of politics at the expense of the “supply” side – ie what the various political actors are, and what they are proposing. But you can only vote for candidates who present themselves, and only choose between programmes that are actually put forward. This is why there’s often a poor fit between the programmes of parties, and what voters say they are voting for.

It’s worth saying a word about the French case, since that’s discussed here. The analysis ignores the fact that the structure of French politics changed a lot between the two graphs, representing roughly the elections of 2012 and 2017. The 2012 election was relatively classic, between an organised Left and an organised Right, with the National Front relegated to third place. As usual, the two sides mobilised the smaller parties to vote for them, and the Left won the Presidential election, and the parliamentary one soon after. This corresponds roughly to the first graph. But by then change had already set in. The Socialist government was a disaster. Bereft of any real ideas, and not wanting to challenge the neoliberal consensus, Hollande fell back on political theatre – letting the identity warriors who made up most of his militants each have their own hour of glory. This produced the catastrophe of the 2017 elections, where the Left did not make it into the second round. But the Right was already in decline, and by 2017 scandals and disunity reduced their vote to the point where they didn’t make it into the second round either. They have carried on collapsing ever since. So the second graph is not surprising, but it doesn’t represent a change of attitudes so much as a change in the subjects of political debate, and the kinds of questions that pollsters ask.

This has produced a bizarre situation where neither of the two major parties in France is of the traditional Left or Right, but that doesn’t mean they are of the mythical “Centre” either. Macron simply encapsulates, in cartoon form, the progressive move towards neoliberal economic and social policies that has typified the last generation. This process has destroyed communities and societies, exported jobs and imported cheap labour, and financialised and casualised the economy. It has also taken the EU from a theatre of action for France to a holy edifice whose word must not be questioned. French politicians take their orientations from Brussels (and partly from Washington) in the sense that their predecessors took them from London, Berlin or Moscow. But even on the extremes of Left and Right, defence of French interests and culture were taken for granted – the French Communist Party was as patriotic as any other, for example.

But all of this has gone now. Macron incarnates the would-be cosmopolitanism and internationalism of the 20% or so of the population who think they are above such things as community, nation and culture (“there is no French culture” as Macron said). They are indifferent to, or even enthusiastic for, the social changes of the last twenty years, and, whilst they educate their children privately in traditional schools they are very happy for the children of the unwashed to be taught to look down on France as an historically imperialist power and the source of many of the world’s problems.

So what do the vast majority of the French people who are unhappy with this state of affairs do? The conventional Left and Right have imploded, and can no longer offer competing conceptions of a republican and democratic France proud of its own history and culture. It’s a sad state of affairs when only Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, with. few small sovereignist parties of Left and Right now occupy the political space where French politics was practiced until recently. That explains the graphs better, I think, than the authors can.

Rev Kev above covered most of the points I was going to make. I have just one thing to add: this entire article is based on a false dichotomy between redistributive policies on the one hand, and protectionism and immigration restrictionism on the other.

There is no reason in principle why a government couldn’t do both at once, and historically several did just that. I am of the opinion that they would even work better if done jointly. After all, for how long can you effectively maintain a functioning Sozialstaat if you have no control over people moving to your jurisdiction? Both redistributionism as well as maintaining higher wages/benefits depend on having some control over the labor force. Isn’t that why labor unions almost always went for the ‘closed shop’ whenever they could–to limit the number of workers in their sector?

Alas, while the center-left parties in the West used to offer something like this, they all began to abandon it back in the 60s for open-borders instead. The ideas seems to have been that they didn’t need the working-class anymore; that they could simply import a whole new electorate instead!

Well, now we see the inevitable consequences of that decision.

Canada today is a contradiction the current policies in many countries. It has become much more multi-cultural, has generally kept many social programs in place, and is generally more tolerant than many countries. It is even apologizing to its First Nations and trying to make amends.

It will be interesting to see what becomes of Canada. Of course, they don’t exactly have open borders, but for a country with such a small population base, they do have a very high rate of immigration.

One more thing: was it Milton Friedman who once said, ‘You can either have open-border or a welfare state, but you cannot long have both at once’? Can’t say in general that I was his biggest fan, but he was definitely right on that point.

The US has never had a “open border” policy (except when it was displacing Native Americans). The southern border has less “illegal entry” than “visa over-stays”. That is not to say uncontrolled immigration doesn’t have economic impacts.

Many of the “Bracero’s” from south of the border who came to the US by Treaty to work in agriculture and construction (because of a shortage of US males–conscripted for WWII) stayed and their children became US citizens. Few people complained about these folks during the economic boom following the War. American employers hired them to do much of the service work that returning GI’s would not do (Better options for them in Steel, Auto’s, Construction.)

Enter Ronald Reagan in the 70’s and 80’s (Calif. Gov./US Pres.) and the decline of labor unions (and wages) and slowly the Supermarket Employee is no longer making a middle class wage. These positions are now held by hard working “immigrants”. The more important issue is livable wages and solidarity among the working class. (That likely includes you and me.)

Birds of a feather flock together – except when a predator enters the area, then prey of a feather flock together and either retreat or attack the common threat – except when you are a predator looking for a meal – then you attack flocks either individually or in flocks of your own feather.

This simple fact of animal life is familiar to most people just by observation. All we see here is the same phenomena only couched in social psychological terms.

Doesn’t it ever cross their minds that the processes of coming up with these categories for political narrative and manipulation are the divisive factor?

Also, the frame of the issues as a problem of belief and identity, and not real problems caused by real policies promoted and enforced by specific institutions and people, still manages to be tone deaf and, to an extent, sets the elite class above examination and reproach.

They frame it as if beliefs and identities are the main factors preventing political action and not people who benefit from heinus policies being the factor behind preventing political change.

And neoliberal “globalists” get downright “nationalist” in their writings about their fears of Russia and China.

It’s a study for political operatives to use, not one that would benefit the formation of social movements.

If western/globalist financial elites/parasites were allowed to take total control of the economies of Russia and China, the way they have with the rest of the world, that fear would dissolve into nothing right quick.

Short version,

Working class citizens will re-elect Trump.

Unless the Democrats nominate Bernie, who will appeal to their common self-interests in National Healthcare, fewer wars and relieving useless student loans.