The beached financial whale known as Deutsche Bank is going to find it awfully hard to get itself back into the drink, let alone find good feeding grounds. After a pop over the news that Deutsche was Doing Something Big, the stock skittered as the CEO Christian Sewing presented more details of the turnaround plan. As we’ll discuss, it didn’t help that the press was unusually skeptical, reflecting the lack of confidence in Deutsche’s scheme among investors and experts.

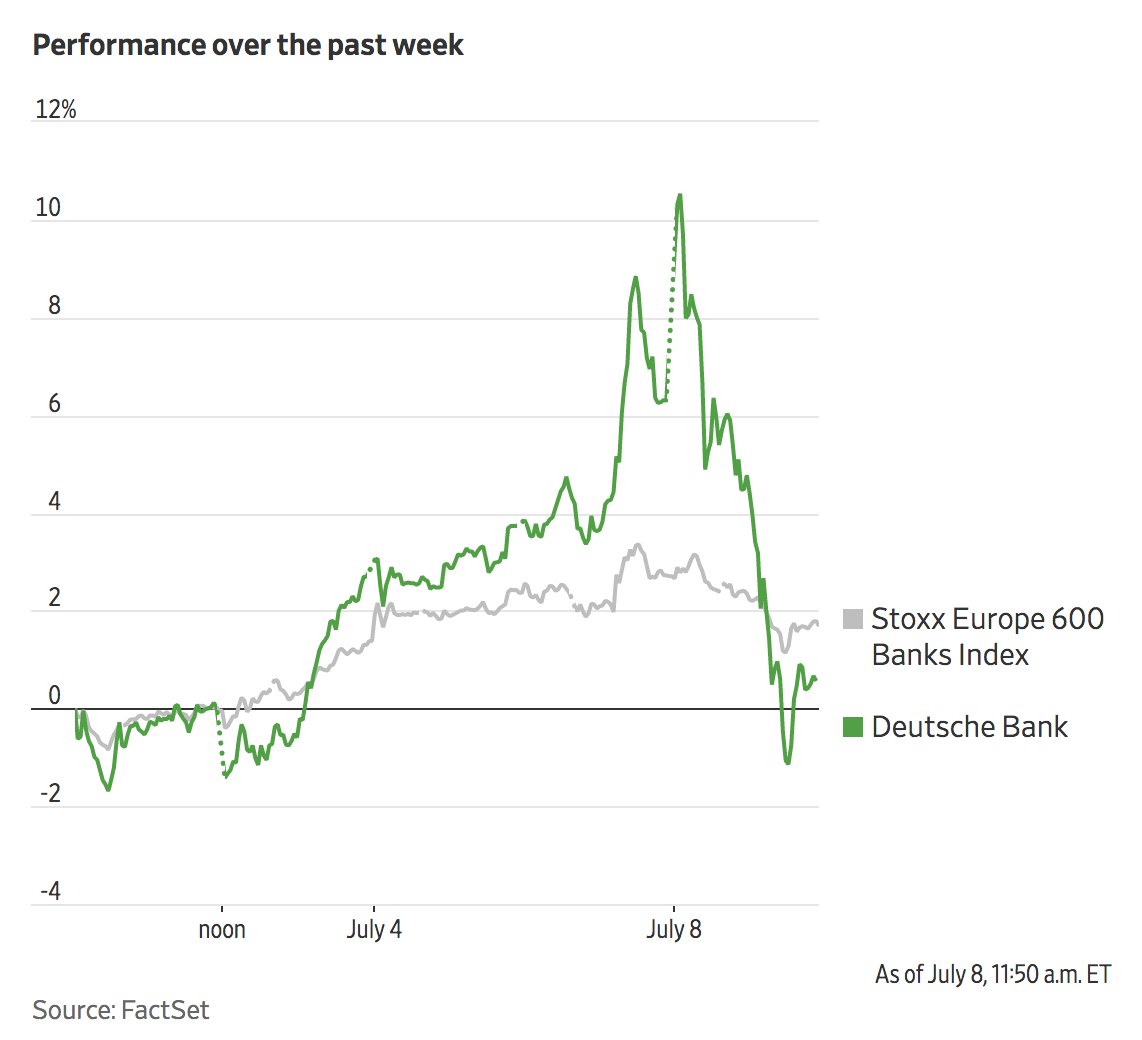

The Wall Street Journal worked up this helpful chart:

Stock prices matter more for sick concerns than for healthy ones1 since their access to credit is usually risky or costly, and if they need more capital or need to fund losses, they have nowhere to go but sell assets or sell new equity. In 2008, leveraged financial firms like the monolines went into death spirals due to the one-two punch of credit and equity funding becoming prohibitively expensive.

Mind you, we’re not saying that Deutsche will come to that sort of end. A combination of zombification and amputations is more likely.

Nevertheless, shareholders, who were initially relieved that the German bank said it wouldn’t need to raise new capital to implement its makeover, saw upon further inspection that those plans are awfully, erm, ambitious. Everything has to break Deutsche’s way for the bank to claw its way back to mere so-so returns. It has not gone unnoticed that the estimated cost of the cleanup of the bad bank, €7.4 billion, is about half Deutsche’s current market value, and Deutsche has also budgeted €13 billion for patching up its IT systems and another €4 billion on improving controls. As Clive put it yesterday, “So where is the inevitable capital needed to support the restructuring going to come from?”

The Financial Times published a long and unusually critical article Monday on Deutsche’s restructuring plan, amplifying doubts that market participants expressed over the weekend about Deutsche’s projected returns:

While it appears that most observers applaud Deutsche’s decision to cut its investment banking operations, that doesn’t mean that there’s a good end game for the bank. Although “synergies” is a badly overused word, there really are a lot of them in investment banking. That costly corporate calling effort, for instance, is more effective the more relevant products you can offer to the target client. “Relevant” means both fit to the corporate customer’s situation and the authority of the contact but is also a function of the bank’s perceived competence in that product. The Financial Times account described some of these issues:

“Further client loss should be anticipated given a reduction in the ‘full service’ investment banking model,” KBW analyst Thomas Hallett said, with clients likely to defect to competitors that offer a broader suite of products and expertise.

Without any equity sales or trading capacity, corporate clients and private equity groups could lose faith in Deutsche’s equity capital markets unit — meaning it could miss out on the lucrative business of underwriting their share sales.

“There is nothing exciting about this plan . . . we worry about the ancillary impact on the client franchise,” said a spokesman for one of the bank’s top-10 investors. “If you’re an asset manager you want to trade equities through the same bank as you trade fixed-income.”….

In any case, significant revenue will disappear. KBW reckons the equities closure will result in €2bn of lost revenue, while a parallel slimming of the bond and rates trading means another €750m could go. That means Deutsche will need to find other ways to increase its core revenue by 10 per cent to the required €25bn to hit its 2022 targets.

For instance, we scratched our head yesterday about Deutsche’s belief that it could exit equity sales and trading while still being able to do some equity underwriting. True, back in the old days, boutiques like Lazard could win some co-manager mandates solely based on the strength of their senior relationship. We had assumed that Deutsche was going to shutter its equity research (or scale it way down to any star analysts that might be important to German clients) since those analysts are a cost center that justify their existence via supporting new issues and the sales force.

But the Journal picked up on a worrisome tidbit. The German bank plans to keep equity research…for reasons that don’t make a lot of sense:

It will also continue to produce equity research as a stand-alone product to sell to institutional investors even though it won’t offer equities trading. The bank said equity and macroeconomic research would support its advisory work for companies looking to do deals or list their shares on stock markets in its remaining equity capital markets business.

“Deutsche has a good product, but it is pretty hard to make money from stand-alone equity research,” said Daniel Davies, a managing director at Frontline Analysts, an outsourcing and training firm for financial analysts. “This may have been cooked up by a manager who doesn’t understand the importance of being in the flow of equity trading when it comes to equity capital markets.”

Ouch. This remark, hoisted from the Financial Times’ comment section, gives further cause for pause:

Sunday Afternoon Three O Clock

Based on anecdotal evidence I’m concerned they’re going cold turkey on traders with complex positions that should be winded down carefully.I hope Deutche is not pulling a Metallgesellschaft on themselves…

It’s also not a good sign that Deutsche was unable to defend its prime brokerage operation, a lucrative business in which it was once one of the top four players. From a March Bloomberg story:

The German firm’s revenue from prime services declined for a third straight year in 2018, while rivals Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. all saw jumps, according to people with knowledge of the business….

The relationship forged by the prime brokerage divisions with hedge-fund clients can often be the lifeblood of banks’ trading units. Deutsche Bank’s decline in the business is symptomatic of the broader prolonged revenue slide that has left the firm struggling to improve profitability and discussing a merger with fellow beleaguered German lender Commerzbank AG.

Deutsche Bank built up its prime brokerage operations in the wake of the financial crisis by seizing on the weakness of its U.S. competitors. In recent years, that dynamic has flipped, with the bank losing customers concerned about its ability and willingness to devote capital to the unit. The firm’s high funding costs and the risk of a credit-rating cut make lending through the prime brokerage less profitable…

On Monday, Sewing stressed it was going to prioritize corporate clients over investors like hedge funds. But all investors are not created equal. Again from the Journal:

That said, it has no plans to trim down its U.S.-focused business of creating and selling risky loans for private-equity backed companies, according to Mr. Sewing, despite widespread warnings from regulators and others of the growing risks in this market.

In the last crisis, banks who were stuck with unsold collateralized loan obligations from the pre-crisis private equity lending boom were rumored to be trading teeny amounts with each other and with friendly hedge funds to enable them to claim fictitiously high valuations. Regulators pretended this sort of thing wasn’t happening due to how bad things were generally; CLOs were far from their biggest worry. The officialdom is much less likely to be forgiving in the event of bad-recession-level losses, as opposed to a full-blown crisis.

And there is also the wee problem of morale. From a Financial Times piece focusing on the firings:

The ripples were felt far wider than those losing their jobs immediately. In Singapore, an employee not directly affected by the cuts told the Financial Times: “The mood is always depressed in Deutsche. People know the bank is not doing well . . . It’s not like a party.”

But even giving Deutsche the benefit of the doubt, and positing that it leaders do a great job of execution, is there really an end game that makes sense? Europe is overbanked. Retail banking in Germany isn’t terribly profitable, which means Deutshe lacks an obvious avenue of retreat. And as vlade pointed out yesterday:

DB’s problem is that it’s too large to serve only German corporates, but too small to do so if it shrinks too much (because those corporates are very much export looking, so you need a good global footprint. EUR was a big hit to bank’s revenues in a way.. ). It also lacks the retail base of the French competitors, and is unlikely to be able to get it (it tried with PostBank, which was another debacle.. ).

In other words, Deutsche looks to lack a good business foundation. Even the best management, which Deutsche sorely lacks, would find it daunting to fix that.

_____

1 Unicorns being an exception that proves the rule.

When I see that Deutsche Bank is targeting improving RoE on Private Banking, my reaction is, yes, you and every other bank in the world.

Private Banking is, for those who are unfamiliar, is a retail product and service offer which caters to the needs of those with significant assets under management and/or income. For a hefty fee, they get some extra bells and whistles (such as multi-currency accounts, jumbo credit card limits, investment advice, plush offices to visit in salubrious areas and especially supercilious bank staff to pander to their whims). Often, a very lucrative bolt-on is “tax advice” or “tax planning”. Here, alert readers might spot that there is at least the potential to sell happier endings to a client’s tax “problems” than the spirit, or even the letter, of law might have intended.

It is, as rapacious, borderline-morality business models go, not a bad one. It lifts the successful provider out of the morass of high-volume low-margin commodity banking services.

But as I stated at the top, no sh1t, Sherlock, everyone in town is onto the notion of attempting to get a piece of the action on this tantalising revenue stream. The customer base demands flawless execution and is possessing of outlandish service expectations. So your cost base is in the stratosphere — premium staffing, office rents for the best places in the best parts of the best tier-1 cities and bespoke systems mean you’re draining cash flow unless you grow the Private Banking customer base to cover it. But stretch everything too thinly and the service proposition gets threadbare and your client base will walk. And if you do recruit high-calibrate relationship managers, you bet-ta keep ‘em sweet (sweetness being expressed as loyalty bonuses, i.e. more cost, a thank-you card and some vouchers for Walmart ain’t gonna cut it here) because if they walk to a rival, they’ll most likely take their well-heeled Rolodex with them, non-compete and non-disparage severance clauses be damned, you’re not going to drag the 5th Avenue matrons and Mayfair tweed-jacket wearers into the witness box to substantiate any legal action to prove wrongdoing.

Deutsche Bank might, just might, make modest gains in this market, if they throw enough money at it. But they might just as well end up digging a big hole, throwing a truckload of cash into it and setting fire to the lot. I know, based on Deutsche Bank’s past history of (mis-) management where I’d bet they’d end up.

Yes, I didn’t focus on that telling detail. Agreed except the 20% they show for asset management looks to be on the low side of industry norms. Google being Google, all I can find on private banking ROE is an old Chicago Fed study saying that 25% is typical…but no idea if that is still true.

In other words, the 5% they show is shocking for an asset management business. But the thought that they can improve returns while increasing the size of their business is too much like trying to walk and chew gum at the same time for this bank.

The only market DB could potentially grow their PB in is if they haven’t captured the owners of German Mittelschafts.

The advantage of this is that them being Germans they don’t really need a lot of the opulence you mention (although they will require the top level service).

The disadvantage of this is that them being Germans they will not pay extra fees for not much, and certainly not for funny exotic products.

So you may grow your client base, but are unlikely to grow the revenues much.

I’m not entirely sure keeping the equity research is as bad as it’s made.

(disclaimer: I have little equity IB experience).

In theory, the banks cannot provide free equity research anymore, at least not in Europe. Part of it was due to possible conflict of interests (which EQ researcher will put a “sell” on client’s stock?).

There are credible specialised EQ research companies, that do no trading at all. So clearly “being close to the flow” is not a requirement. It’s hard, true. But possible.

Asset management, which DB wants to support more, is a good consumer of EQ research. W/o it, the AM has a gaping hole. Of course, the problem here is that you cannot give your clients the hot not-so-public info (that you’re not supposed to give anyways, but somehow has a way making it there..).

Lastly, good researchers (macro, FX, EQ you name it) are essentially a PR for any bank, more than anything else. That’s why you often get a few with extreme views and/or people who can write very readable (and often funny) research pieces. It makes good press = good PR.

And, TBH, in the end, the EQ research costs tends to be not that huge (compared to other bits) – it’s mostly staff related so if you look at it as a PR costs, it’s likely to be ok.

I’m more worried about the unwind of complex structures. I’ve been in a situation having to deal with structures that were put in place by other people, and it’s often a mess. Sometimes, admittedly, because the new people find risks in the structures that the previous people didn’t realise, ignored or just wilfully misinterpreted.

TLDR; of below: The problem with those complex trades/structures is that they may have wider implications than just the bank, often unexpected by other parties.

RMBSes, especially non-US ones, tend to require swaps to be well rated. These swaps on the first glance look fairly vanilla (some uncertainty around notional, but nothing that special). On a closer glance though, they have a full gamut of legal clauses which makes them pretty complex. One of those clauses is that the counterparty providing the swap, at certain rating, has to start posting collateral (which tends to be a lot if the swap is a cross-currency, which it often is, we’re easily talking hundreds of millions per swap). At even lower ratings, the cpty is required to find a replacement party.

Enter RBS. They wrote quite a few of those before 2008, as it seemed free money. Amongst others, they wrote a lot of the swaps for Norther Rock vehicle, Granite.

2008, RBS rating went down, and they found themselves posting tons (billions of pounds, required literally overnight) of cash at the worst possible moment.

Then RBS went down to BBB-, which is one of those triggers requiring you to find a replacement cpty.

Well, except there’s really no mechanism that can enforce that. And while RBS would actually like to novate those swaps to someone else, it wasn’t willing to do it at any price. And there were few, if any, takers in the market for this type of product. TBH, RBS was very unrealistic on the prices it was willing to pay, most likely due to the fact it knew there were no contractual penalties and the govt would not let it sink anymore. I know, I was talking to RBS on this at the time.

Anyways, while there were no contractual penalties for RBS, the rating agencies had a different mechanism – downgrading the bonds.

Which made the investors very unhappy, since the underlying quality of the bonds was the same (here I’ll point out that no investor lost on Northern Rock RMBS, or indeed any UK RMBSes, a single cent in credit losses. The ones that lost were the ones who sold during the NR panic. I know of traders who took second mortgage at that time to buy the bonds at about 10p to pound IIRC, and made a killing when the price recovered), but, from their view, an obscure event they didn’t even see on their radar was hurting their investment.

I’m pretty sure DB has stuff like above, that can hurt not just DB, but others, who most likely have no idea it can hit them.

I also believe that a lot of the complex, structured stuff that ends up in the “Capital Relief Unit” will be there till maturity – which may be decades. These will be either with corporates, who did it as some sort of hedge, and will not be willing to unwind, or with hedgies, who may be willing to unwind but at a steep price. I’ve heard 3bln bandied around as the cost DB may be willing to pay for someone to take all that stuff on. That’s IMO way optimistic – getting out of a deal like I described above with RBS can easily run into tens of millions pounds or more (that is in addition to the current NPV), so the above would be able to pay for say a few hundreds of deals like that.

For example, from the public info. In 2013 DB did a longevity swap with Carrilion. Let’s say that longevity swap is one of the most obscure derivatives, where going through the full documentation (which likely will run into hundreds of pages) with a fine comb is a must. They also often run for decades.

I do not doubt that DB tried to back out (do equal but opposite) trade with some reinsurers (who like the longevity risk for their life insurances). The question is, did they do it perfectly, or by some mistake (or not), managed to keep some risk on? That will be a key part in how much capital it’s eating, and how easy it may be to novate (assuming the other parties actually agree!). Again, the pension funds may have some rating triggers attached – and if DB can’t/won’t novate, they would mean trouble..

Another example may be swaps linked to the UK inflation. Those were often part of the UK utility bond issuances, and as such have often embedded inflation options. In theory, inflation options are traded in the UK. Well, the only problem is, it’s a very thin one-way market (there are no natural sellers of the options, only buyers). So you end up with these uncovered option positions. In practice, most of them would requre deflation for long periods to pay out, so _look_ safe. Except we’re in low rates, low inflation environment, and these options may have maturities in decades. So the risk models give them non-trivial risk.

Oh, did I mention that these trades are also in a similar position like the swaps for the RMBSes I wrote above?

I could go on, but this is really just to give a feeler of the problems..

I for one very much appreciate the level of detail in your post, vlade. Thanks for that

Ditto here. Thanks, vlade. Have been wondering about potential effects on DB’s derivatives counterparties. This from Pam and Russ Martens’ Wall Street on Parade blog yesterday:

… “before you get too comfortable with the notion that it’s okay if an American bank is beating the socks off a German bank, you need to remember two things: Deutsche Bank is a major derivatives’ counterparty to most of the big banks on Wall Street according to a 2016 report from the International Monetary Fund — its health, or lack thereof, could spill over onto Wall Street; and, secondly, there’s nothing to prevent another London Whale-style trading fiasco from blowing a hole in JPMorgan Chase’s federally-insured bank – putting you, the taxpayer, at risk.”

And it’s not just taxpayers that are at risk, as we saw in the 2008 financial crisis WRT the nation’s payments and depository system. After over ten years of “foaming the runway” for them with massive Quantitative Easing and Negative Real Interest Rates courtesy of the Fed, ECB and BOJ, it is again clear that the large TBTF banks need to be broken up and the Glass-Steagall Act separating commercial and investment banking reinstated and the exploited loopholes closed.

I’m pretty sure DB has stuff like above, that can hurt not just DB, but others, who most likely have no idea it can hit them.

I’m reminded of the knock-on effects of Lehman Bros failure causing the near collapse of AIG. (enter bailout)

Even back to the days when equity commissions were fat, equity research was recognized as a cost center and one that depended on adequate underwriting and commission revenues to justify its existence.

It is very hard to make a living as an independent research boutique. And they get paid cash or have the IBs allocate credit to them out of commissions.

DB could not charge hard $ for research (unless it sold “white label” research to small fry; this was a business 15 years ago and I have no idea if this is still the case). This simply isn’t done by big integrated financial firms, plus there is a question as to how independent DB’s research would be

It would be paid only from underwriting mandates or its own commissions….which aren’t happening due to getting rid of sales and trading. No way would a competitor allocate research credits to DB.

Maybe in the US.

In the EU, MIFID 2 requires that firms pay for the investment research (not just on EQ, but all financial products. Basically, only macro econ research, unless it talks about currencies or rates too much is out I believe) explicitly. Any execution and research services must be unbundled, and be avialable and priced separately.

FCA has explicit rules to bar “offering research as inducement to buy trade execution services”

So at least in Europe, DB has no option but to charge hard $ for it (I believe there may be exceptions where the research can be provided for free, if it’s publicly available on entirely non-discriminatory basis, but am not really that much across this space).

I have read investment opinion elsewhere that Deutsche Bank financial leverage is far higher than comparable banks. Given that, the concerns outlined above by Yves and Clive, combined with the “everything bubble” state of many financial asset classes , the further massive proliferation of derivatives and increased international financial connectedness, could Deutsche Bank become the Lehman Bros of 2019 or 2020?

Or will the newly minted ECB chief Mme. Lagarde ride in on a white charger to stop the first big domino falling?

Those collateralized loan obligations (CLO’s) are the ticking time-bomb here. They keep rearing their ugly head in my readings over on wolfstreet.com (oft-cited source on NC).

Unlikely since a lot of derivatives have been moved over to central counterparties. The authorities are worried about a CCP default. Look at how one bad trade at NASDAQ blew through over 60% of its reserves.

Even though CLOs are technically a type of CDO, they don’t share any of its bad design features (resecuritization, which ginormously increased the risk of blowup, and “cliff risk”, that a small change in losses on the mortgage securitizations [from 8% to 11%] made the difference between the CDOs being money good to a total bust).

In other words, CLO blowups if and when they happen won’t look like CDOs. They are lower risk than straight-up risky corporate lending, but that in turn looks like it will lead banks to be too complacent about risks and pile them on. Too much of any kind of stupid risky lending will founder a bank.

Too much of any kind of stupid risky lending will founder a bank.

Just wanted to repeat that.

This raises the question: do the current TBTF bank managers understand what is a stupid risk? Or, do they believe that a bank’s TBTF size eliminates any ‘stupid risk’ (to the bank and themselves), and therefore there is no ‘stupid risk’?

The risk management function at banks is separate from business generation and is deliberately kept weak for political reasons. Bank senior executives and too many analysts get upset when a big financial firm isn’t writing lucrative-looking business. I remember the high fives at Sumitomo Bank when it got $30 million in up front fees for lending $500 million to Robert Campeau in a late-in-cycle LBO deal which Fortune called “The biggest, looniest deal ever”:

http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1990/06/18/73686/index.htm

One priceless line:

Campeau went bankrupt in pretty short order.

Keynes has arguably the best take on banks as lenders:

To an extent, the new market risk regulation (so called FRTB) is attempting to take it out of the bank’s managers hands, at least for tradeable-ish products (syndicated loans and the like avoid it).

For example, it makes the old play of “too much capital in trading book? Move to banking”, which was practiced around GFC with abadon uviable (it makes such moves subject to regulatory approval and only for good reasons like large restructures, mergers etc, and it also requires that the larger of two capital charges will be used in any such move).

It also explicitly prohibits use of internal risk models on any securitisation products.

It still has drawbacks, as it tries to capture exotic risks via a notional % charge (so called Residual Risk Add On), but these are not additive. So if you have a bunch of different exotic risks, it treats them the same way as if you had just one.

But still, it’s considerably more capital intensive than before. Criticaly though, while the US made noises about adopting this, it didn’t do much more than noises. And unless it’s adopted globaly, it’s not worth much.

Now that the German real estate market is topping out, I wonder how all of the highly leveraged commercial real estate loans will work out for DB when the market goes sideways.