Yves here. This Wolf Richter provides some important context on the status of the dollar. Recall that 1994 was just after the fall of the USSR and hence during peak US hegemony, at least militarily. And independent of the Trump Administration’s considerable self-inflicted wounds, the position of the dollar as reserve currency should be expected to diminish over time as US share of global GDP falls.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

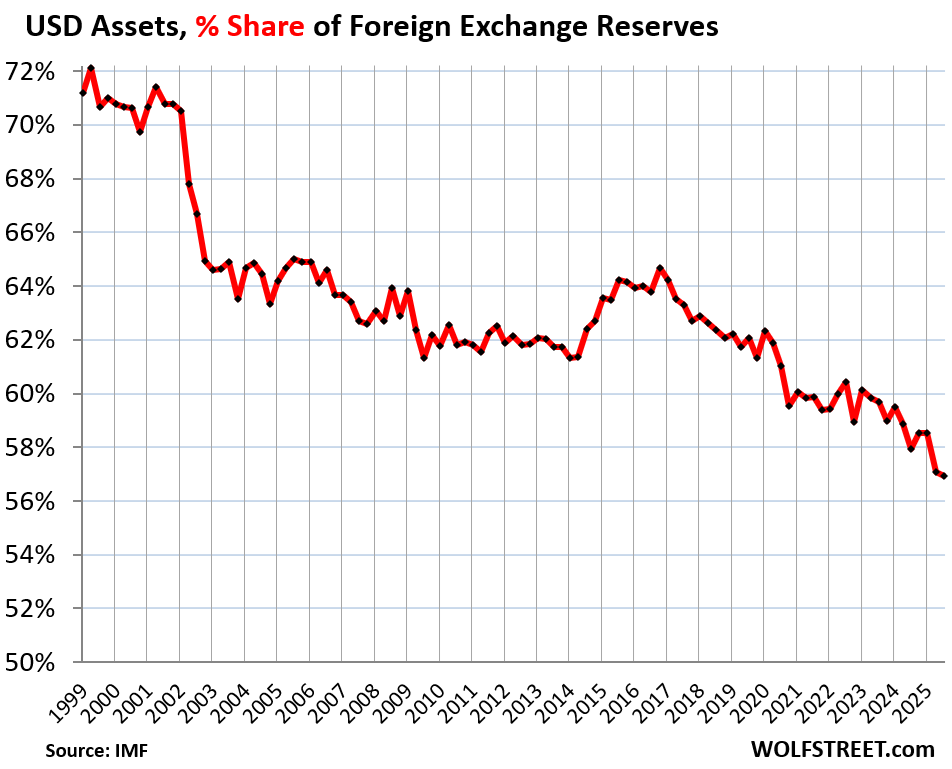

The share of USD-denominated assets held by other central banks dropped to 56.9% of total foreign exchange reserves in Q3, the lowest since 1994, from 57.1% in Q2 and 58.5% in Q1, according to the IMF’s new data on Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves.

USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves include US Treasury securities, US mortgage-backed securities (MBS), US agency securities, US corporate bonds, and other USD-denominated assets held by central banks other than the Fed.

Excluded are any central bank’s assets denominated in its own currency, such as the Fed’s Treasury securities or the ECB’s euro-denominated securities.

It’s not that foreign central banks dumped US-dollar-denominated assets, such as Treasury securities. They did not. They added a little to their holdings. But they added more assets denominated in other currencies, particularly a gaggle of smaller currencies whose combined share has surged, while central banks’ holdings of USD-denominated assets haven’t changed much for a decade, and so the percentage share of those USD assets continued to decline.

As the dollar’s share declines toward the 50% line, the dollar would still be by far the largest reserve currency, as all other currencies combined would weigh as much as the dollar. But it does have consequences.

Why Is Having the Top Reserve Currency Important for the US?

Foreign central banks buying USD-denominated assets, such as Treasury securities, helps push up prices and push down yields of those assets. Being the dominant reserve currency had the effect of helping the US borrow more cheaply to fund its huge twin deficits – the trade deficit and the budget deficit – and thereby has enabled the US to run those huge twin deficits for decades. At some point, this continued decline as a reserve currency, as it reduces demand for USD debt, would make the trade deficit and the budget deficit more difficult to sustain.

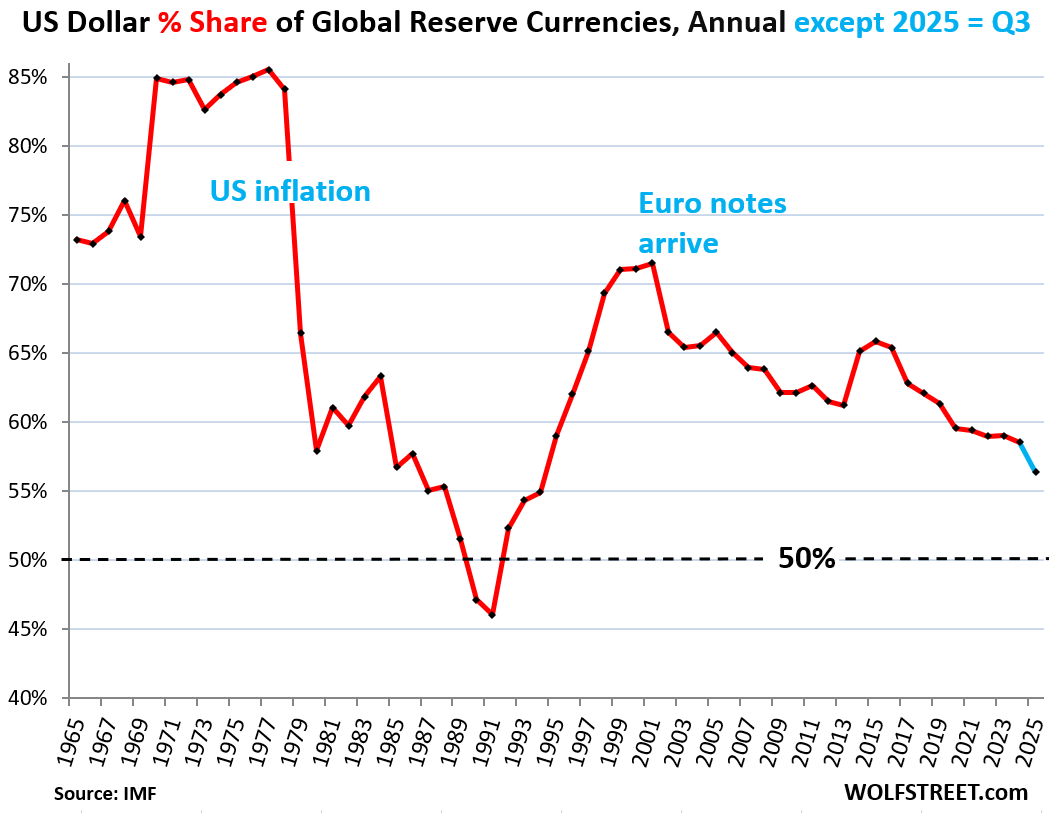

The dollar’s share had already been below 50% before, in 1990 and 1991, after a long plunge from the peak in 1977 (share of 85.5%). This plunge accompanied a deep crisis in the US with sky-high inflation and interest rates, and four recessions over those years, including the nasty double-dip recession. Central banks lost confidence in the Fed’s willingness or ability to do what it takes to get this inflation under control that had washed over the US in three ever larger waves.

The dotted line in the chart below indicates the 50%-share. The dollar’s share bottomed out at 46% in 1991, by which time the Fed had brought inflation under control, and soon, central banks began loading up on dollar-assets.

Then came the euro, which turned into the next set-back for the dollar, but not nearly as much as European politicians had promised when pushing the euro through the system; they were talking about parity with the dollar. That talk ended with the Euro Debt Crisis that began in 2009.

Then, over the past 10 years, came dozens of smaller “non-traditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them.

The chart shows the dollar’s share at the end of each year, except 2025 where it shows the share in Q3:

But They Didn’t Actually Dump USD-Denominated Securities

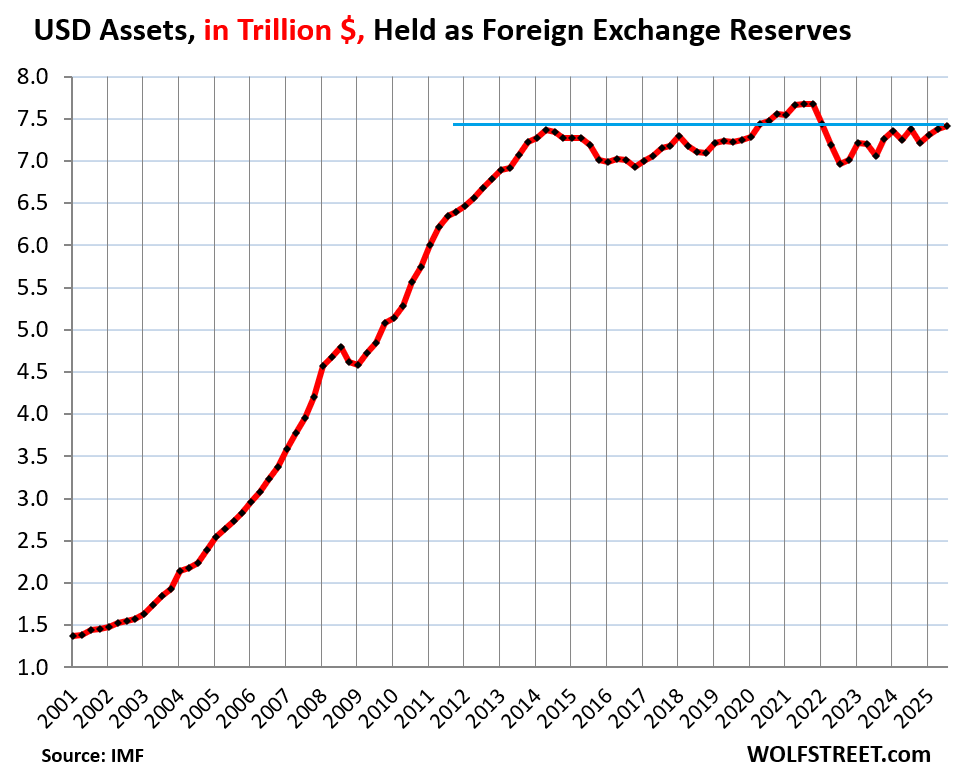

Foreign central banks increased their holdings of USD-denominated assets by a hair in Q3 to $7.4 trillion, the third increase in a row.

Since mid-2014, despite some sharp ups and downs, their holdings of USD-assets have remained essentially flat.

So, what has caused the percentage share of USD assets to decline over the years is the growth of foreign exchange reserves denominated in other currencies, particularly many smaller currencies, as central banks have been diversifying their growing pile of foreign exchange assets.

The chart below shows foreign central banks’ holdings of USD-denominated assets – US Treasury securities, US MBS, US agency securities, US corporate bonds, etc. – in trillions of dollars:

The Top Foreign Exchange Reserves by Currency

Central banks’ holdings of foreign exchange reserves in all currencies, and expressed in USD, rose to $13.0 trillion in Q3.

Top holdings, expressed in USD:

- USD assets: $7.41 trillion

- Euro assets (EUR): $2.65 trillion

- Yen assets (YEN): $0.76 trillion

- British pound assets (GBP): $0.58 trillion

- Canadian dollar assets (CAD): $0.35 trillion

- Australian dollar assets (AUD): $0.27 trillion

- Chinese renminbi (RMB) assets: $0.25 trillion

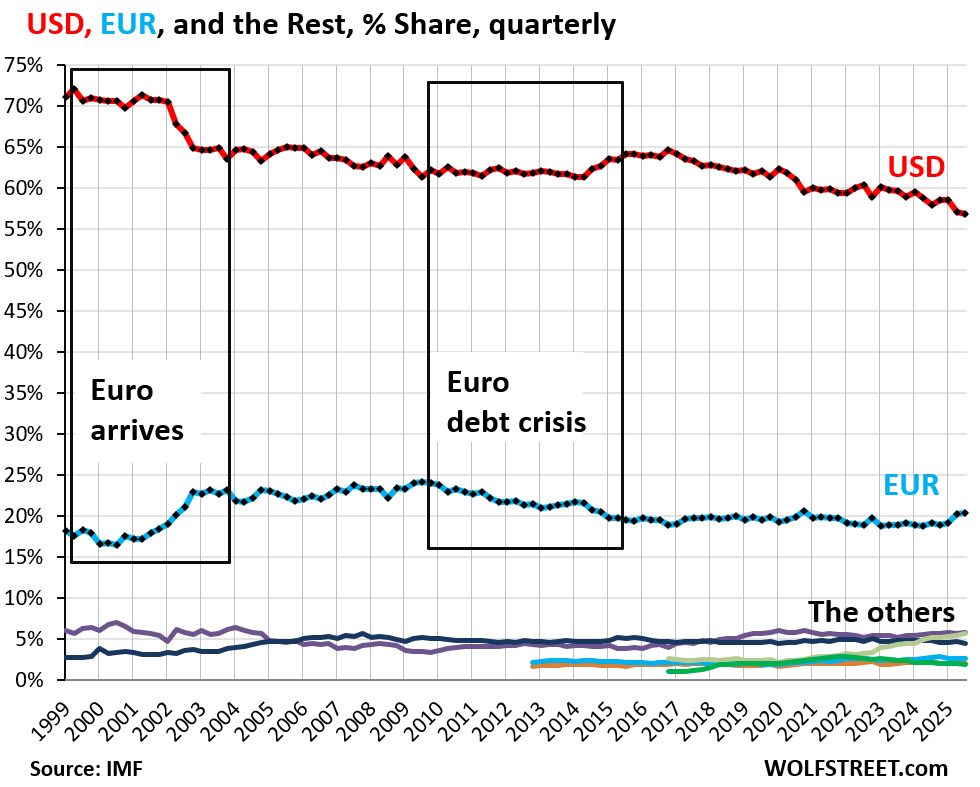

The euro’s share, #2, has been around 20% since 2015. Before the Euro Debt Crisis, it was on an upward trajectory and had already risen to nearly 25%.

The rest of the reserve currencies are the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the chart (more in a moment). Combined, they have gained share over the years, at the expense of the dollar, while the euro’s share has remained roughly stable since 2015.

The rise of the “non-traditional” reserve currencies

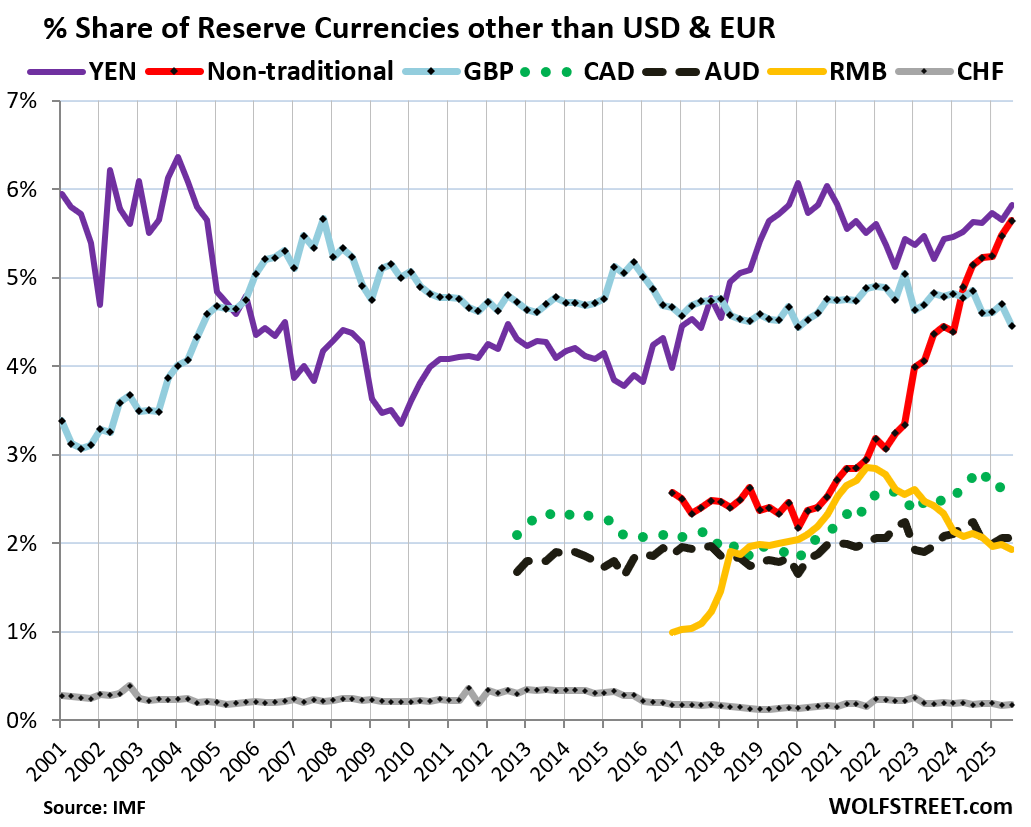

The chart below takes a magnifying glass to the colorful spaghetti at the bottom of the chart above.

The soaring red line shows the combined surge of assets denominated in dozens of smaller “nontraditional reserve currencies,” as the IMF calls them. Combined, they reached a share of 5.6%, just below the yen-denominated assets (5.8%).

But the share of the RMB (yellow) has been declining since Q1 2022, and its share is now back where it had been in 2019, amid ongoing capital controls, convertibility issues, and a slew of other issues.

In other words, the USD and the RMB both have given up share to the “non-traditional reserve currencies” as other central banks have been diversifying away from assets denominated in USD and RMB.

In case you missed my update on a slightly less ugly situation: US Government Interest Payments to Tax Receipts, Average Interest Rate on the Debt, and Debt-to-GDP Ratio in Q3 2025

That Kevin Walmsley was talking about US debt in a recent post and pointed out something significant. That countries were seeking loans denominated in RMB rather than US-denominated loans as they pay less than half in interest charges compared to US dollar loans. As an example, ‘Kenya’s railway authority converted their USD loans to renminbi, and will save $215 million per year.’ The IMF has been wagging their finger at this development as it is “risky” but they would say that, wouldn’t they. This is only a recent development since 2022 as US interest rates kept rising because of high inflation and giant fiscal deficits so maybe it is a permanent development-

https://kdwalmsley.substack.com/p/more-countries-prefer-to-borrow-rmb

*Sigh* This is the mistake countries always make, of focusing on the nominal interest rate in the borrowing currency. This is the fast track to a foreign currency crisis. This was what you saw in the Asian financial crisis.

The lower interest rate reflects the high odds of appreciation of that currency and higher future cost.

If they believed as most do that the dollar is set to fall in value, they’d be better off in probable all in costs to borrow in dollars. But any politically-connected party would be attacked over the higher (versus dollar) initial cost.

Borrowing in RMB is quite possibly the stupidest thing any African country could do right now. The RMB is actively managed to maintain an artificially low value. There are very strong pressures (internally and externally) for the RMB to revalue to a significantly higher level. If that was to happen it would be enormously destructive to any African country with RMB denominated debt.

What if the Chinese were willing to restructure the debt after a currency revaluation?

There was a link posted here a while ago where Varoufakis was mentioning how the Chinese were willing to restructure debt they had with Greece when the original deal wasn’t working so well for the Greeks. If I remember correctly, this was the rather large deal they’d made to purchase the controlling share in the port of Piraeus.

Contrast that with the common US practice of selling off bad debts to the likes of Paul Singer and letting the vultures feast on small countries roped into bad deals.

As the USD seems to be closer to a true floating currency, the differences in future economic results compared to the RMB does seem to provide more uncertainly with these sorts of business decisions. Our friend Warren Mosler has been discussing central bank rates with a floating currency, but I can’t seem to find a focused statement.

Now that brings up an interesting development. Supposing that the Chinese did revalue the RMB higher. The spread right now between the RMB and the US Dollar is over two percent but is widening. Even now, if the Chinese revalued the RMB by 2%, it would still be cheaper than the US Dollar whose interest rates continue to climb.

“At some point, this continued decline as a reserve currency, as it reduces demand for USD debt, would make the trade deficit and the budget deficit more difficult to sustain.”

Warren Mosler had been pointing out, imports are a benefit, exports are a cost. It will be difficult to sustain only if other countries refuse to accept dollar payments for their traded items.

For a sovereign currency issuing state, a budget deficit is a boon for its domestic private sector provided constraints on inflation. AFAIK, per MMT insight, issuing debt is not the only option for funding budget deficits.

Exports are also how imports are paid for. The alternative is debt and the additional cost of interest.

Walmart imports a lot of stuff (at least before the tariff war started).

What does Walmart “exports” to pay for their imports?

Walmart buys low and sells higher, they make money on by selling goods for more than it buys them, after expenses – of course. American consumers are the ones who are paying for the imports, the expenses and Walmart’s profits.

When consumers buy more than they make, they go into debt and are responsible for paying back that debt plus interest. When a country imports more than it exports, it goes into debt as well. At the same time we have to be careful because not all imports are alike. A country could import machinery and technology, then invest in domestic production. When the production becomes profitable, it will be in a position to sell more than it buys and pay off its debt. If a country has a trade deficit made up of imported consumer goods, then it is running up a debt without necessarily increasing production. The debt is usually in the form of cash, and the exporting country may hold it, or buy assets from the importing country. Usually these assets take the form of shares in companies from the importing country, its real estate, corporate or government debt. Everything is cool, as long as the creditor (exporting) country is willing to hold the importing country’s debt. Once that changes, there is downward pressure on the debtor’s currency and upward pressure on its inflation and interest rates. The US federal government has over $38 trillion in debt and every 1% increase in interest rates will eventually cost the country an additional $380 billion in annual interest payments.

The question as posed by MMT is, I think, not helpful: “imports good or bad?”

My take: for a nation’s strategic long-term mercantilist advantage, imports of industrial equipment are generally beneficial, but imports of consumer goods are not. Exports of industrial goods might be good or bad, exports of consumer goods are definitely good.

I’m sure there is a theory with a name for this concept, elaborating endlessly.

Exceptions will be made for bananas and coffee- imports of tropical fruits and drugs are definitely good for a country’s mood.

MMT does not pose questions. This is a category error. Nor does MMT make value judgements. Some of its advocates do in making policy prescriptions based on MMT that diverge from what mainstream economics practitioners see as sound.

Thanks for this. The absolute values and percentage share numbers show that for all the chatter about multi-polarity etc, it’s still pretty much business as usual, but for a couple blips.

This is good to know. More fuel for the fire … :)

#TransnationExternalSectorCommonCurrencyDreams

This is FRED WSEINT1, looking at its history you have to wonder whether the US has much control over these balances or they are just a representation of the reality of their increasingly financialised economy.

Gold now outweighs US Treasuries across global central banks. This is due to banks buying gold and the recent steep appreciation in gold.

This factoid even if true is not terribly meaningful since the US has far and away the largest gold reserves, for instance, more than 3x of those of China.

https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/gold-reserves

MURICA

🇺🇸

Silver at $78.. That’s…….Nuts. With the Chinese limiting exports, it may go even higher still.

Causing $ 17 billion in repo on Boxing Day with more to come. Some of the silver movement is undoubtedly due to the Eastward movement of markets but major moves in silver usually means the party is about to be over. Perhaps things have changed but the silver market is usually the last holdout of the worst scoundrels.