Lambert here. Pretty dry language: “Perhaps one must go beyond simply comparing economic models by considering legal and political factors?” Then for example, in the US, Trump would be one “externality” of the Crash. In the UK, Brexit would be another. “Perhaps.”

Marcus Miller, Research Associate, ESRC Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy, University of Warwick; CEPR Research Fellow, and Lei Zhang, Professor in the School of Economics, Sichuan University. Originally published at VoxEU.

Much of recent innovation has led to products that make cheating the public easier.

Joseph Stiglitz, 2019.

How the UK system of market-based finance might behave under stress is evidently an important policy issue, as witnessed by a Bank of England working paper by Aikman et al. (2019). Key features discussed are creditor runs that can lead to fire sales, with prices falling enough to threaten insolvency.

In planning for the future, one can learn from the past – and the near collapse of the US shadow banking system is a case in point. Some of the US’ most prestigious banks seemed to have found a form of alchemy where mortgage lending across the country could be financed by raising funds at low rates on Wall Street. On the asset side, the secret was securitising subprime assets, on the liability side – tapping money markets for wholesale funding (Tooke 2018). This seems to contradict the Scottish proverb ‘Ye can ne make a Silk-Purse of a Sowe’s Luggs’,1 but the credit rating agencies did their best to help out!2

What of the Basel rules to limit risk taking? Alas, thereby hangs a fallacy of composition on the part of regulators – compounded by liquidity illusion on the part of shadow banks.

In a new paper (Miller and Zhang 2019), we use the model of Shin (2010: Chapter 3) to study the amplification effect that can operate despite value at risk (VaR) regulation. It’s rather like what happened on Wall Street in the 1920s, when rising share prices increased the value of collateral of those speculating on the stock market, so they could borrow more, so prices went higher, and so on … until the crash of 1929. We also look at the crash of 2008!

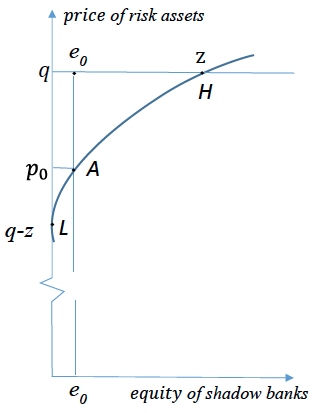

Amplification under the VaR rules is indicated in the figures that follow. Figure 1 illustrates the point that greater participation of highly-leveraged, risk-neutral players in the market will raise the price of risk assets, measured on the vertical axis – with q denoting the expected payoff and q-z the lowest payoff. On the horizontal axis is the equity of shadow banks, given a fixed supply of risk assets, normalised to unity.3 As risk-neutral shadow banks effectively ‘crowd out’ risk-averse lenders, the market price rises from L (where the price matches q-z) to H (where the price matches q). Even though shadow banks are risk- neutral, the price can lie below q as VaR regulation requires banks’ own equity to cover the downside risk – so low equity limits their demand. With initial equity of e0 for example, the asset price will be p0, as shown at point A.

Figure 1 Price of risk assets higher if shadow banks ‘crowd out’ risk-averse lenders

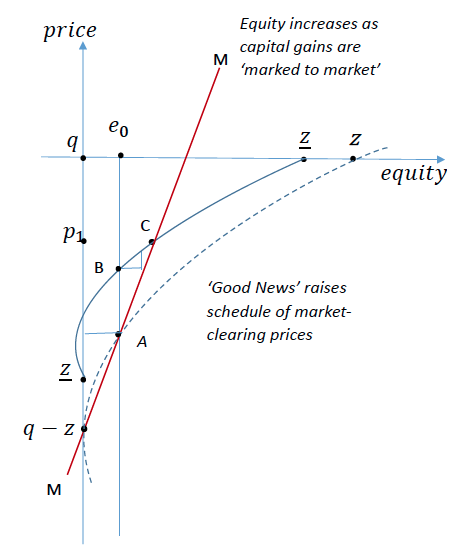

Charles Goodhart (2011) maintained that the VaR regime suffered from a ‘fallacy of composition’, since the regulators believed that ensuring each bank covered downside risk on its portfolio would ensure the safety of the system as a whole. Considerable amplification of news shocks will, indeed, occur if banks ‘mark their assets to market’, for the equity base of the leveraged sector becomes endogenous (pro-cyclical), as indicated by the line MM passing through point A in Figure 2.

‘Good news’ of a reduction in downside risk (from z to z), which raises asset prices from A to B without marking to market, will get amplified when equity is revised to incorporate capital gains. So, after a series of markings, equilibrium arrives at C. Shadow banks will doubtless be gratified with their capital gains and increased market share, and the VaR regulations have been satisfied – so why worry?

Figure 2 Asset prices and equity rise in response to ‘good news’ of lower downside risk

What if there is ‘bad news’? “The amplifying mechanism works exactly in reverse on the way down”, writes Shin (2010: 35). In fact, however, things can get much worse if the ‘bad news’ triggers creditor panic, and withdrawals lead to fire-sales that threaten insolvency. As Bernanke (2019) explains:

Panics emerge when bad news leads investors to believe that the ‘safe’ short-term assets they have been holding may not, in fact, be entirely safe. If the news is bad enough, investors will pull back from funding banks and other intermediaries, refusing to roll over their short-term funds as they mature. As intermediaries lose funding, they may be forced to sell existing loans and to stop making new ones.

In our work, where a bank run is added to Shin’s account of ‘bad news’, it leads to prompt systemic insolvency.4 In reality, of course, the US Treasury responded with capital injections (of over 2% of shadow bank assets) and the Fed provided liquidity support to those shadow banks not yet taken over,5 and purchased mortgage-backed assets under quantitative easing.

Without this, it seems clear that the shadow banks would have become insolvent, which is what Gertler and Kiyotaki (2015) concluded in one of a series of papers they have written “to develop a simple macroeconomic model of banking instability that features both financial accelerator effects and bank runs”. For them, the ‘bad news’ takes the form of a negative productivity shock of 5% on the payoff on bank assets, which triggers a fall of 15% in asset values if a bank run follows – enough to wipe out shadow bank equity. As the run is attributed to a ‘sunspot’, however, it seems that they are twice victims of bad luck – from a large unanticipated productivity shock plus from an unfortunate incidence of creditor panic.

This is a very different perspective from Akerlof and Shiller (2011: Chapter 2) who attribute insolvency to bad faith and not bad luck, alleging that banks and credit rating agencies had effectively colluded to mis-sell securitised assets way above their true value.6 In their terminology, the ‘good news’ outcome was a crash-prone ‘phishing equilibrium’, where those with better information secured profits by mis-selling to those with less. This is a serious allegation – yet, as far as we know, no legal action has been taken against them. Could this be because, in a raft of court cases, US shadow banks – and their European counterparts – have escaped criminal charges by confessing misbehaviour, promising to reform and paying large fines7 (with the credit rating agencies also making such deferred prosecution agreements regarding collusive behaviour)?8

Technically, the Shin model, with ‘fake news’ and bank runs9, and that of Gertler and Kiyotaki, with productivity shocks and sunspots, produce similar results, namely, losses by highly leveraged shadow banks leading to fire-sales and potential collapse. Ethically, however, they differ greatly. How to choose?

Perhaps one must go beyond simply comparing economic models by considering legal and political factors? Findings in US courts of law have already been mentioned – with banks and credit rating agencies subject to numerous and costly deferred prosecution agreements. No senior executives have been sent to prison in the US, nor in the UK, however.10 What of political repercussions?

For the US, Michael Lewis sees the election of Trump as president as “an unfortunate aftershock” of the financial blunders of the last decade. In his view:

The collapse of the US mortgage market and the subsequent bailout of the banks left Americans of varying political views feeling that the system was rigged. I think of this as echoing the 2008 financial crisis (Silverman 2016)

For the UK, the consequences may be even more dramatic. The geographical correlation between suffering post-crisis austerity and voting to leave the EU, leads Nicholas Crafts (2019) to argue that the ultimate costs of the financial crisis for the UK should include GDP losses on leaving. With the election of Boris Johnson as prime minister, leaving is much more likely – with some risk that exit without agreement may lead to the break-up of the UK.

Are these the results of ‘technology shocks and sunspots’, or signs that ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark’?

I’ve been convinced that most ‘improvements’ in computers over that last 5 years or so has had the effect of hiding the predation going on behind the scenes on internet connected devices.

Much of the time spent loading webpages is connected with interrogating your PC to see where else you’ve been, what you’ve been doing, and with who, and sharing that data with entities that sell that data to advertisers and other ‘interested parties‘.

Over time, this interrogation and sharing had become deeper and broader, and had impacted the performance of the computer, and thus the user experience, enough to be noticeable, and of course, irritating, but as processors got faster and memory became cheaper the degradation of performance could be masked and that made for happier, if still clueless users.

In the end it looks to me as if we are clamoring for, and running to procure machines that more efficiently surveil our every move while more and more efficiently hiding that fact.

And we think we are so smart.

See yesterday’s post on dark patterns. That’s exactly what’s going on.

Yes, we need Ita.

As Lambert notes, exactly.

But it is not new. I attended the Univ. Calif. Santa Barbara (which was linked to DARPAnet) in late 60’s. Back then IT folks recognized that anonymity while using that network was impossible. (Passing “secret” info among a group of research scientists required high security (no anonymity)). As that network transmogriifed into today’s Internet, anonymity is merely an IP and MAC address away from personal identification. It was Google that leaned to use this network system info, cheap data storage and a search engine to monetize your activity on the Internet. Now everybody is doing it.

Artificial intelligence now can figure out who you are even without IP or MAC addresses, simply by looking at patterned activity. There are only so many MacBooks accessing Naked Capitalism on a monday morning.

Trump as President doesn’t impress me. What did the financial crisis have to do with a historically inept Bush Presidency souring Republican’s on their politicians(which was the real reason for the Trump rise in the RNC)?

Trump was a anti-Bush vote inside the Republican caucus then Biden not being able to emotionally build himself up to run which turned the DNC into a trainwreck. That left the Clinton political machine and anti-Clinton vote in Bernie Sanders. If Biden was the candidate as expected before his son’s untimely death, Clinton may have not even run. Her massive unfavorables in the party and Sanders massive unfavorables with Indies was a huge problem for the DNC. Clinton forced out all other moderate candidates while Sanders stopped any other social democrats from running to water down his vibe. It was a super small, sad field that frankly, with anybody other named than Donald Trump would have been crushed in November. The Red Sea Conspiracy and its psyops was just kicking them while they were down(even though the RSC ultimately did not lead toward a deal with the Trump Organization, it swayed enough indies on single issues and evangelicals who import illegals for the Republican party to help push a electoral victory).

I think Lewis needs to understand economics, especially in modern post-industrial life isn’t what it used to be in the suburbs or cities. It doesn’t explain all elections, nor does it explain Donald Trump. The Iraq war was a massive flop for Bush that hurt Mittens in 2012 and led to a outsider to get the nomination. Lewis needs to understand INSTEAD the economic anxiety in agricultural areas played a bigger role in the election after the 2015-16 commodity bust which saw Democrats take a larger beating than usual, especially with white women. It was enough to swing the electoral college in 1 state at least. Maybe all 4.

Now the producer side of the economy looks exhausted though. That is for another post.

It’s not really that complicated. Bezos and Zuck simply realize that the web is unregulated.

Amazon and Facebook and Uber are not innovations. Amazon is just mail-order, using the same technology as Sears and Penneys. Phone in the order, deliver by truck. Facebook is gossip, using the web instead of back fences and phones. Uber is a taxi service that you call by phone. The only innovation is that you CAN’T use a landline phone to call Uber, while you CAN use a landline to call a real taxi. That’s a limitation, not an innovation.

Because the web is unregulated, it enabled the “innovators” to escape laws and taxes that were enforced in the older mail and phone systems.

Something similar happened in the first decade of radio from 1920 to 1930. Cult leaders and fraudsters got rich using the unregulated airwaves. The party ended in 1934 when the FCC started to enforce laws.

Neoclassical economics doesn’t consider debt, the money supply and banks. This is where all the problems have been developing out of sight and out of mind.

In 2008 the Queen visited the revered economists of the LSE and said “If these things were so large, how come everyone missed it?”

It’s that neoclassical economics they use Ma’am, it doesn’t consider debt.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

Richard Vague ran a credit card company in the US and he couldn’t help notice the runaway mortgage lending before 2008 just by looking at the numbers.

https://www.ineteconomics.org/research/programs/private-debt

(Watch the video)

The banker’s weapon is complexity, and they wrap everything in complexity.

The banker’s only real product is debt and they use this in various complex ways to cause financial crises.

Strip off the complexity and get to the base, bank credit.

Steve Keen saw 2008 coming in 2005 by looking at the private debt-to-GDP ratio; 1929 and 2008 stick out like sore thumbs, see chart above. The complexity on top is different, underneath they are pretty much the same.

This is how China saw its Minsky Moment coming and they told everyone at Davos in 2018 that the private debt-to-GDP ratio and inflated asset prices are the best indicators of financial crises.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1WOs6S0VrlA

Richard Vague has now looked back at 200 years of financial crises and nearly everyone is preceded by runaway bank lending that can be seen in the private debt-to-GDP ratio.

“A Brief History of Doom” Richard Vague

Bankers only have one real product and that’s debt, look there before they layer up the complexity on top.

I think that the link above to opendemocracy is old and now invalid. At least it didn’t work for me.

Here are some books on debt that I found educational: The web of debt by Ellen Brown I believe that this book is available for free on line) and debt: The first 5000 years byDavid Graeber. The Center for Public Inegrity also produced a report Debt Deception. Actually all these are available on-line.

Another book that indirecly discusses debt is Rigged by Dean Baker.

It is here at 18 mins.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

Another trick is misleading naming.

If you call an insurance product a “Credit Default Swap” it is still an insurance product.

If Credit Default Swaps had been regulated as an insurance product, AIG wouldn’t have gone down.

AIG sold lots of these insurance products, but put nothing aside in case they needed to pay out. They didn’t have to as they weren’t regulated as insurance products.

When they did have to pay out, AIG went down.

Shadow banks play a crucial role in helping regular bankers shift their debt products to maximise profit.

Banks loans create money and their activities are closely monitored.

Shadow banks don’t create money and their activities are not that closely monitored.

A bank working with a shadow bank, but not legally connected to it, gets around the regulations.

The bank can create the money to lend to a shadow bank that can then engage in the dodgy sort of lending practices the bank can’t. When the shadow bank gets into trouble, it can’t make the repayments on that money borrowed from the regular bank.

They used to use the term “conduit” and that’s a good way of describing the shadow banks role in allowing banks to get around bank regulations. Once that money, borrowed from a regular bank, has passed though the “conduit” it can be loaned out in ways that the bank couldn’t directly.

This is what happened in Japan.

“Jusen” were nonbank institutions formed in the 1970s by consortia of banks to make household mortgages since banks had mortgage limitations.

The shadow banks were just an intermediary put in place to get around regulations.