Yves here. It has been reported in venues like the Financial Times that importers who would face increased costs from tariffs on China were taking steps so as not to increase prices to customers, which includes making their suppliers give better prices and eating some costs too. With profit share at a record high level relative to GDP, there’s room for that sort of thing. However, lower profits ought to mean lower stock prices, so Mr. Market has gotten that memo. And one would expect stock-price-orieinted CEOs to work longer term on reducing their China exposure and/or squeezing labor harder to restore any profit hit. But in the meantime, inflation isn’t the vector by which the China tariffs are affecting the US economy.

Having said that, Wolf is unduly fond of the notion that tariffs generate Federal revenue. I hope he someday gets the memo that a sovereign currency issuer does not need to tax in order to spend.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

The consumer price inflation data released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which corroborates prior inflation data, says that, yes, prices are rising, but they’re rising sharply in services that are not impacted by imports and tariffs, such as rents and other housing costs, healthcare, education, and other services, and also in restaurants (where customers pay mostly for labor and rent). But inflation in durable goods, such as electronics, cars, and the like – where the tariffs would show up – was very low.

Inflation as measure by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 0.3% in July from June and 1.8% over the 12-month period. This was largely held down by a decline in energy costs (-2.0% due to the ongoing oil bust) and by a very slow rise in the costs of durable goods.

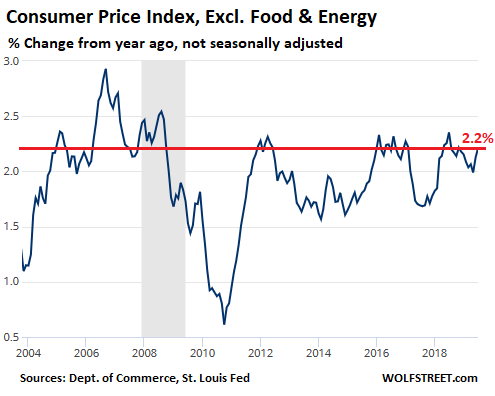

Food and energy prices are very volatile, dancing to the tune of oil busts, droughts, floods, diseases in animals, and other factors. Together, they weigh about 21% in the overall CPI. A less volatile measure is the CPI without food and energy, or “core CPI,” which rose 2.2% over the 12-month period, at the high end of the 10-year range:

Where Does This Inflation Come From?

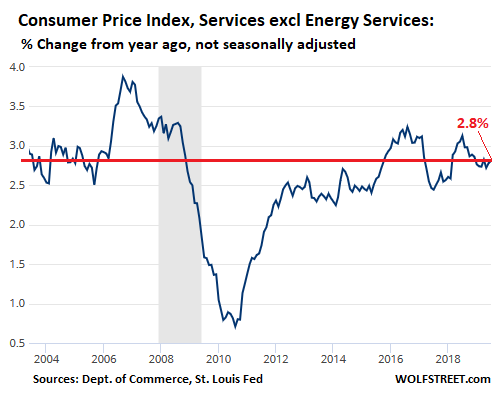

Primarily Services: Services include the biggies that consumers spend most of their money on: housing costs, healthcare, financial services, telecommunications services, education, etc. Services without energy services (such as utilities) weigh about 60% in the overall CPI. These services have nothing to do with imports or tariffs, and over the 12-month period, their prices jumped 2.8%:

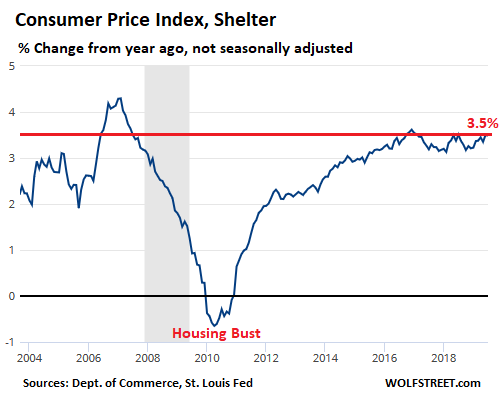

“Shelter,” the biggie, accounts for 33% of the overall CPI. “Shelter” is a group of services that includes housing costs, such as rents and “owner’s equivalent of rent” (what it would cost a homeowner to rent the home), plus hotels, and the like. Shelter has nothing to do with imports or tariffs, and it jumped 3.5% over the 12-month period, at the very top of the 10-year range:

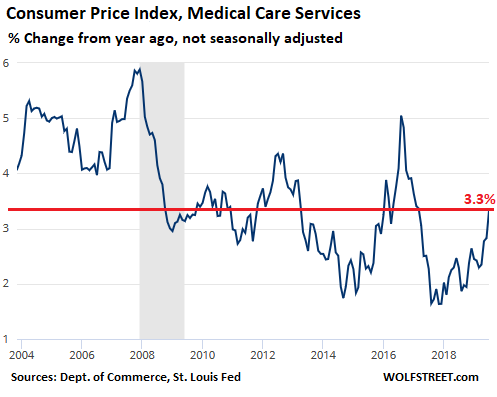

Medical care services, the second largest group in services, account for about 7% of total CPI. This does not include pharmaceutical products, but includes hospital services, dental services, and the like. And it includes health insurance, which – as we guessed with our grin-and-bear-it grimace – soared 15.9% over the 12-month period, driving prices of total medical services up by 3.3%:

Where Does This Inflation Not Come From?

Durable Goods – products like cars, furniture, appliances, TVs, smartphones, computers, tools, lawnmowers, etc. A lot of products in this category are imported, or even if the products are “made” in the US, their components are imported. This is where tariffs would hit the hardest.

A reminder what inflation is and is not. Inflation is a price increase of the same item with the same qualities and features, and the same quantity or size. If new cars get better – improved safety features, performance, electronics, etc. – this cost of the improvements shows up in a higher price of the car, but is removed from the inflation data. Same with smartphones, and other products. A $800 laptop today is a thousand times more powerful and feature-laden than a laptop in 1995 that cost $2,400.

Many durable goods are far better than they were, but cost less, such as laptops. Other products cost more, but you’re getting a better product. Your cost of living goes up because you buy those improved products, and because you buy products that didn’t exist before, such as smartphones. In return, you’re presumably safer and more comfortable and better connected and get better quality of life of whatever. That’s the theory. Inflation is when the same thing with the same qualities gets more expensive.

By this measure, deflation in durable goods has long been common. As manufacturing (automation) and transportation get more efficient, the same products should cost less. Globalization of manufacturing has contributed to that, as US companies offshored production to cheap countries.

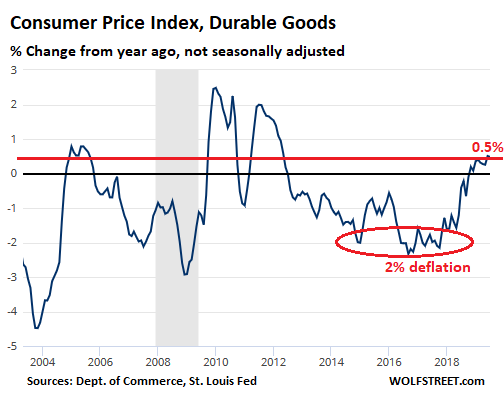

The Consumer Price Index for durable goods inched up 0.5% in July, compared to a year ago (and a slightly slower rate than the year-over-year increase in June). In the Fed’s eyes, while an improvement over the -2% range (deflation) in 2016 and 2017, it was still insufferably low inflation. Some upward pressure in prices of durable goods – tariffs or no tariffs – would bring the Fed to its goal, and it can get off its “low inflation” bandwagon. But we’re not there yet:

Corporate America, focused on offshoring production, hates tariffs. Foreign companies, focused on sending their goods to the US, also hate tariffs. They’re first in line to pay for the tariffs. Their hope is that they can pass them on to consumers. But they’re having trouble doing so.

Consumer prices in the US are not set by companies but by the market (unless there is a monopoly or a screwed-up situation as in healthcare where there is no market). Walmart might want to raise the prices of its Chinese stuff, but consumers can buy this stuff elsewhere, and they can dig up the lowest price on the internet. This causes Walmart to lose a sale. Price increases in goods that can be comparison-shopped over the internet have had a very hard time sticking.

Corporate America just received a large income-tax cut. And companies didn’t pass those tax cuts on to consumers. Tariffs are the opposite, but on a smaller scale: They’re a tax increase on corporations, both US importers and foreign companies exporting to the US. But they impact profit margins on sales, rather than taxable income.

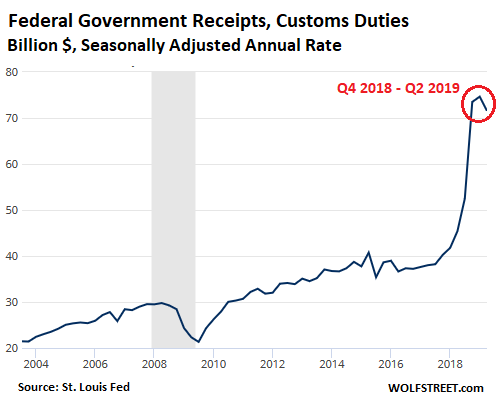

If in the future foreign and US companies are finally able to raise prices on durable goods – tariffs or no tariffs – and make them stick, it might finally cause the Fed to get off its “low inflation” bandwagon and declare that long-sought-after “victory” of having met or exceeded its target. Meanwhile, these tariffs bring in big revenues to the US government, having doubled from prior years to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of over $70 billion, and the government sure needs that moolah:

In the US alone, “Financial Repression” impacts nearly $40 trillion — with consequences for the real economy. Read… The Giant Sucking Sound of Financial Repression

I wish I could find a couple of ancient posts that analysed the evolution of US economic sectors dividing them in dynamic and stagnant. Just to see if their conclusions were coherent with current sectoral inflation rates. Using a computer instead of a smartphone I could have done it.

Ok, I found it: Market Power, Low Productivity, and Lagging Wages: The Real Drivers

.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2018/08/market-power-low-productivity-lagging-wages-real-drivers.html

The sectors qualified as stagnant in terms of productivity growth seem to be the most inflationary right now.

I’d love to see a article where someone can help me understand what is going on with housing. Ten years ago, I read that we had enough extra homes in the U.S. to house all of the U.K. and more. Did we grow that much in 10 years? I’m in the midwest, and prices are crazy, and in my neighborhood there has been almost nothing listed this year. One house listed in the last month and it sold within 48 hours. There has been very little inventory in my area.

To follow developments on housing in the US Calculated Risk (do websearch) is a very good place. Yet, I am worried with housing rent prices and really don’t understand why those are climbing so much in so many countries.

A few years ago I saw a figure that 7 million homes had been purchased and turned into rental units since the great recession. Within the past 6-months the NYT ran an article that placed the number lower, maybe 4 or 5 million. They admitted that their number was probably on the low side.

With interest rates at record lows and the stock market … There has also been a push to hold real assets. So some large corporations, but mostly individual investors bought up houses and have turned them into rental units. As rental units they don’t turn over. They have effectively been taken off the market and the inventory of homes for purchase (supply) has been reduced. This is not the only factor, but is an often overlooked factor.

I know a handful of people who have done just this. At the extreme one owns 4 or 5 dozen houses that are leased out.

Is all housing occupied?

Certainly not in Vancouver, Toronto nor London where real estate is increasingly under scrutiny as a money laundering vehicle.

I remember reading a couple decades ago that ~50% of all the homes in Maine and Vermont were 2nd homes. That doesn’t seem to have changed – here’s a guide to the % of 2nd homes in the US broken down by county – http://eyeonhousing.org/2018/12/nations-stock-of-second-homes/

While there are a lot of 2nd homes nationwide, there are not all that many in the midwest according to this data so not sure why there is a shortage in your area. This website defines a 2nd home as a non-rental property though and we know a lot of inventory has been taken over for use as for-rent illegal hotels (aka Airbnb). There are definitely a lot of those in the areas which also have high 2nd home rates, so in New England for example the problem is likely even worse than the chart indicates, causing even more housing to not be occupied full time. Also not sure if the midwest has the same problem with illegal hotels as the coastal areas do though.

I think its too early to tell if tariffs have an effect on inflation.

First of all, the tariffs are not on the final retail price but based on the price that’s on the commercial invoice for an item and presented to CBP at a port of entry. This price is based on what the cost to the importer is, and typically, it is a small fraction of the final retail price.

For example, a ten percent tariff on Nike slave made running shoes, which cost Nike $5 bucks would draw a 50 cent tariff while the final retail price is $200

A one percent discount at retail is four times greater than the 50 cent tariff.

I deal with plenty of industrial tool dealers who show you how much the tarriffs are adding to your bill every time you order any given object. Too bad we can’t make those things here in the USA, huh? Many items have been on back order all year, and the tarriffs typically add around 15% to my total costs.

Are those dealers showing you the price on the commercial invoice at time of entry into the US? Without that information, one doesn’t really know, and furthermore the dealers themselves are most likely a customer of the importer, or even further removed by being a customer of the wholesaler that is a customer of the importer. So there could be several levels of markup between you and the importer, and a modest tariff grows to a substantial amount after all the percentage markups are applied by the wholesale and dealer levels.

Price increases are more easily pushed onto customers when there is a lot of confusion and misinformation about prices, and tariffs provide cover for that.

They have got you paying 15% more, and blame tariffs. It doesn’t pass the smell test for one simple reason. Nothing has had a 15% tariff applied. It’s either 10% or 25% of the price on the commercial invoice, so if tariffs were the sole reason for the price increase it would be either 10% or 25% depending on the item.

A 15% price increase seems stiff. Compare that to the 350% price increase handed to some post office customers, from one day to the next.

Lots of pain to go around.

It’s not just the internet. The German grocery chain Lidl came to town and put a store across the street from my nearby Walmart. Now when you walk in the Walmart they display two full grocery baskets with signs showing the price of the Walmart basket of goods versus Lidl. Arguably both Lidl and competitor Aldi are Walmart imitators with labor costs cut to the bone and a heavy reliance on store brands to provide reasonable (most of the time) quality at the lowest possible price. Bezos studied Walmart as well and used low prices and no sales tax to fuel his rise.

For sure retail is exploiting its workers with low wages reflecting a supply/demand advantage on the labor end. But from a customer standpoint it’s one area of American business where competition is still a thing.

In microeconomics class in college, we learned about “price discrimination” which was how, e.g., the same tube of toothpaste is priced at $2 in US but $0.50 in a third-world country.

What happens when the Chinese-made toothpaste probably costs $0.10 to make/deliver to the store shelf, and now it costs $0.20 with tariffs? Probably the same $2 price to the consumer.

I will say I’m not clear on whether the toothpaste manufacturer is currently charging the store $0.50 cost, or if they charge them $1-1.50.

I hope he someday gets the memo that a sovereign currency issuer does not need to tax in order to spend. Yves Smith

Nor does a sovereign currency issuer need to have positive yields or pay interest on its inherently risk-free debt, including account balances at the Central Bank (aka “bank reserves”).

To do so anyway not only provides welfare proportional to account balance but also subsidizes foreign imports.

Over in 2pmwc today Lambert posted a link with this title: “ACA market continues to lose those who don’t qualify for financial help | Health Care Dive”.

Connecting the dots, the most interesting statistic from Wolf’s piece above for me was the following:

“…health insurance … soared 15.9% over the 12-month period…”

Gee, I wonder if that might have something to do with the loss of unsubsidized participants from the market. See, if more people were just *smarter* health-insurance shoppers, I’m sure we could knock those annual premium hikes down into a more reasonable 14-15% range. /sarc

But just keep chanting in unison, as the MSM do it: “Obama ACA good, Orange-hair Satan tariffs bad!”

The graphs shown in the article do not support the thesis of the article: the increase in inflation for durable goods (from – 2% to +0.5% = increase of 2.5%) is in fact the sharpest increase in inflation of all the sectors shown.

So from this one should conclude that tariffs did in fact increase inflation (although the numbers are still low and it is still too soon).

I think the article is mixed because, while it correctly explains why there is some deflation in durable goods (because of increased productivity), it then ignores what it just said and thinks that 0.5 inflation in the same goods is low.

No – Wolf makes clear that durable goods had seen several years of 2% *deflation* until this latest YoY uptick of 0.5%. Consider an item with unit cost 100, which has 2 years of 2% deflation and then one year of 0.5% inflation – here are the resulting yearly prices:

2017: 98.00

2018: 96.04

2019: 96.52

A 0.5% YoY increase means just that – 0.5% inflation, not 2.5%. Compare to healthcare, setting the baseline price level 100 one year ago, just to illustrate the last-year trend there:

2018: 100.00

2019: 115.90

Which of those sectors suffered the higher YoY inflation in the past year?