Yves here. Even though the mere use of the word “productivity” might lead readers to expect a wonky post, this is a highly accessible treatment when the argument is clearly stated. More like this, please.

Mind you, that does not mean I find all elements of author Blair Fix’s argument equally convincing but the spare exposition is commendable.

By Blair Fix, a PhD student at the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University in Toronto, Canada. His PhD work focuses on the development of a biophysical economic growth theory. His first book, ‘Rethinking Economic Growth Theory From a Biophysical Perspective‘ , was published in 2015. Twitter: @blair_fix. Originally published at Economics from the Top Down; cross posted from Evonomics

Did you hear the joke about the economists who tested their theory by defining it to be true? Oh, I forgot. It’s not a joke. It’s standard practice among mainstream economists. They propose that productivity explains income. And then they ‘test’ this idea by defining productivity in terms of income.

In this post, I’m going to show you this circular logic. Then I’ll show you what productivity differences look like when productivity is measure objectively. They’re far too small to explain income differences.

Marginal Productivity Theory

The marginal productivity theory of income distribution was born a little over a century ago. Its principle creator, John Bates Clark, was explicit that his theory was about ideology and not science. Clark wanted show that in capitalist societies, everyone got what they produced, and hence all was fair:

It is the purpose of this work to show that the distribution of the income of society is controlled by a natural law, and that this law, if it worked without friction, would give to every agent of production the amount of wealth which that agent creates. (John Bates Clark in The Distribution of Wealth)

Clark was also explicit about why his theory was needed. The stability of the capitalist order was at stake! Here’s Clark again:

The welfare of the laboring classes depends on whether they get much or little; but their attitude toward other classes—and, therefore, the stability of the social state—depends chiefly on the question, whether the amount that they get, be it large or small, is what they produce. If they create a small amount of wealth and get the whole of it, they may not seek to revolutionize society; but if it were to appear that they produce an ample amount and get only a part of it, many of them would become revolutionists, and all would have the right to do so. (John Bates Clark in The Distribution of Wealth)

So the neoclassical theory of income distribution was born as an ideological response to Marxism. According to Marx, capitalists extract a surplus from workers, and so workers get less than what they deserve. Clark’s marginal productivity theory aimed to show that this was not true. Both capitalists and workers, Clark claimed, got what they deserved.

The message of Clark’s theory is simple: workers need to stay in their place. They already earn what they produce, so they have no right to demand more.

The Human Capital Extension

Clark created marginal productivity theory to explain class-based income — the income split between laborers and capitalists. But his theory was soon used to explain income differences between workers.

In the mid 20th century, neoclassical economists invented a new form of capital. Workers, the economists claimed, owned ‘human capital’ — a stock of skills and knowledge. This human capital made skilled workers more productive, and hence, made them earn more money. So not only did productivity explain class-based income, it now explained personal income.

With the birth of human capital theory in the 1960s, the marginal revolution was complete. All income differences, economists claimed, could be tied to productivity differences. And from then onward, there was an endless stream of empirical work that ‘confirmed’ that productivity explained income.

A Sticky Problem: How Do We Compare Different Outputs?

Before we look at how economists ‘confirm’ marginal productivity theory, we have to backtrack a bit. We have to understand a basic problem with the concept of productivity.

Imagine we want to compare the productivity of a corn farmer to the productivity of a composer. The corn farmer produces corn. The composer produces music. How do we compare these two outputs?

I think it’s obvious that we cannot do so objectively. Any comparison will require a subjective decision about how to convert corn and music into the same dimension. The lesson is simple. We cannot objectively compare the productivity of two workers unless they produce the same thing.

Think about how severely this problem undermines marginal productivity theory. The theory claims that productivity differences universally explain income differences. But we can never actually test the theory, because productivity differences cannot be universally measured.

Even worse, it’s possible to earn income without producing anything. Think about the practice of patent trolling. Patent trolls are people who buy the patent for a product that they neither invented nor produce. These individuals don’t ‘produce’ anything. But they still make money. How? Because they get the government to enforce their property rights. Patent trolls sue (or just threaten to sue) anyone who infringes on their patent. Viola, they earn income without producing anything.

My point here is to show that marginal productivity theory is plagued by a simple problem. We can’t compare the productivity of people who produce different things. And some people don’t ‘produce’ anything at all. This problem seems to severely limit any test of marginal productivity theory.

Economists’ Sleight of Hand: Defining Productivity Using Income

Given the problems with comparing the productivity of workers with different outputs, you’d think that marginal productivity theory would have died long ago. After all, a theory that can’t be tested is scientifically useless.

Fortunately (for themselves), neoclassical economists don’t play by the normal rules of science. If you browse the economics literature, you’ll find an endless stream of studies claiming that wages are proportional to productivity. Under the hood of these studies is a trick that allows productivity to be universally compared. And even better, it guarantees that income will be proportional to productivity.

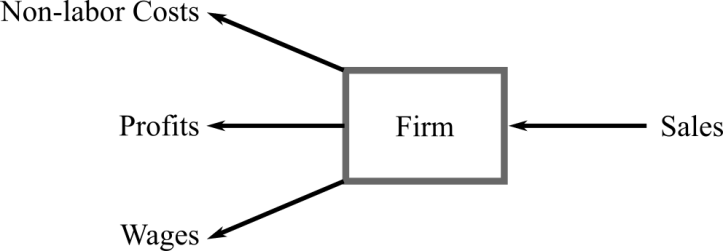

To understand the trick, we have to look at some basic accounting definitions. Figure 1 shows how a firm’s income stream gets split. The firm earns income in the form of sales (right). Part of this income is paid to the firm’s owners as ‘profits’, and part of it is paid to workers as ‘wages’. The rest goes to other firms as ‘non-labor costs’.

The point here is that the income on the right (sales) is the source of the income on the left (profits and wages). So a larger income on the right translates into larger incomes on the left. Thus sales per worker will obviously correlate with wages. Given our accounting definition, it has too.

With our accounting definition in hand, we’re ready for the trick used by neoclassical economists. To test their theory, they define ‘productivity’ in terms of income! They assume that a firm’s sales indicate its ‘output’.

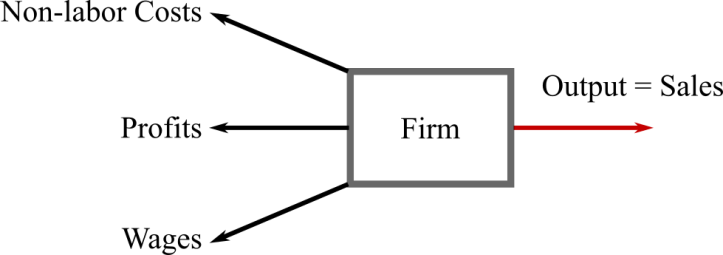

Figure 2 shows this slight of hand. Neoclassical economists take the firm’s income stream and reverse it’s direction. Presto! Sales now indicate output! [1]

With this slight of hand, we can endlessly confirm that productivity ‘explains’ income. We find that productivity — as measured by sales per worker — is highly correlated with wages!

The key here is to forget that we are dealing with an accounting truism. Sales are no longer ‘income’. Sales are now ‘output’. And this output miraculously ‘explains’ wages!

I wish I could tell you that this is a joke, since it doesn’t pass the laugh test. But it’s not. Measuring ‘productivity’ using sales (or value added) is standard practice in mainstream economics.

And so economists test their theory of income distribution by assuming it is true. They measure productivity in terms of income. Then they find (unsurprisingly) that productivity ‘explains’ income.

How To Show That Productivity ‘Explains’ Income:

I’ve taken the liberty of creating a step by step guide for how to test marginal productivity theory and guarantee that the theory succeeds:

- Find an income-accounting equation that is true by definition.

- Forget that you are dealing with an accounting equation.

- Pick a form of income (in your equation) that you want to explain.

- Given your choice, look at the opposite side of your accounting equation.

- Convince yourself that this opposite side no longer measures income. It now measure output.

- Regress the two sides of your accounting equation.

- Celebrate when you find a strong correlation.

- Claim you that have found evidence that productivity explains income.

- Never tell anyone that your results were guaranteed because they followed from an income-accounting equation. (This step is unnecessary if Step 2 is successful).

Productivity Differences Cannot Explain Income Inequality

Neoclassical economists resort to slight of hand to measure productivity differences, and so endlessly confirm their theory. But what happens if we try to measure productivity differences objectively?

We find that productivity differences cannot possibly explain income inequality.

To measure productivity objectively, we can only compare workers doing the same task. For instance, we can compare the productivity of two workers who make rivets. Or two workers who both deliver mail. Since the workers have an output with the same dimension, we can objectively compare their productivity.

Here’s an interesting question: how much does productivity vary among workers doing the same task? The psychologist John E. Hunter spent much of his career answering this question. According to his results, the answer is ‘not very much’.

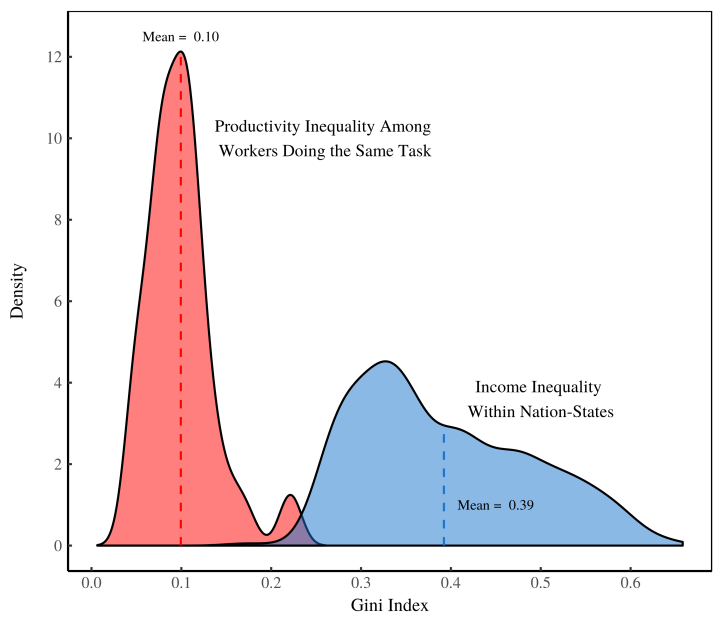

Figure 3 takes Hunter’s data and compares it to data on income inequality within countries. Let’s break down the results. First, I measure inequality using the Gini index, which varies from 0 (no inequality) to 1 (maximum inequality). In Figure 3, the x-axis shows the Gini index. The y-axis shows the ‘density’, or relative frequency, of the particular Gini value.

The red curve in Figure 3 shows the Gini index for workers’ productivity. For each task reported by Hunter, I’ve converted the workers’ productivity differences into a Gini index. The red curve shows the distribution of Gini indexes for all of the reported tasks. According to Hunter’s data, differences in workers’ productivity clump tightly around a Gini index of 0.1.

Next to this productivity data, I’ve plotted the distribution of inequality within all the countries of the world (the blue curve). The average Gini index within these countries is about 0.4.

The lesson here is that differences in workers’ productivity are tiny compared to differences in income. So it’s inconceivable that productivity differences (as measured here) can explain income inequality.

Let’s Kill the Productivity-Income Thought Virus

The idea that income is caused by productivity is a dead end. Marginal productivity theory only survives because economists never test it objectively. Instead, they resort to slight of hand. They measure productivity using income, and claim that this ‘confirms’ their theory.

Let’s not mince words. Marginal productivity is a thought virus that is sabotaging the scientific study of income. It needs to die.

Notes

[1] Economists will often subtract non-labor costs from sales to calculate ‘value-added’. They’ll then claim that value-added measures firm output. It’s the same slight of hand, since they’re still converting an income stream into an ‘output’.

May it RIP. With the rest of us.

> Even worse, it’s possible to earn income without producing anything.

That would be the majority riding on the backs of the minority. Its called the service economy.

Think of eclownomist, Larry Summers, while servicing the elite he was so productive that he lost billions to his bankster buddies, and his reward is to be paid millions to flap his gums and spew gibberish. Produces less than nothing, and is grossly overpaid for it.

Same with Bernanke, warming a chair in a Pirate’s office for millions, producing nothing as a reward for past service.

How is productivity measured for a bankster? The moar debt he or she loads on your naive shoulders, the moar productive they are.

High-frequency trading by having your computer close to the exchange so you can front-run trades is the epitome of income without producing anything. It provides zero (actually probably negative) economic and productivity benefit but generates a lot of income and wealth.

Gather ’round the campfire, because I’m going to tell you a little story.

Very early in my working career, I learned that productivity was a bunch of BS. I was a high school student and was absolutely thrilled to get a part-time job at McDonalds.

Well, I had one heckuva time getting on the schedule, and, when I did, I was relegated to cleanup duty. And, guess what. I did a great job of keeping the lobby, the dining area, and the parking lot clean.

The manager loved to praise me for my great work on the cleanup beat. Oh, did he ever. Although I repeatedly asked him for training in other areas, well, sorry, Slim. You’re on cleanup duty because you’re good at it.

Oh, well.

Over time, I started to notice other things about that manager. He was 43 years old and was married to a 20-year-old woman.

Together, they had a toddler son. ISTR that little Al was 4 years old. Do the math on that one. Bob the manager had fathered a child with a 16-year-old.

Well, you’d think that a cute toddler son and woman less than half his age would have been enough for Bob, but it wasn’t. He was after several of the girls in the McDonalds, and the ever-efficient store grapevine reported that he had, ahem, succeeded with two of them.

In modern parlance, his behavior would have been called grooming. If you were female, you were on the receiving end. I know this because I experienced it. And, in case you’re wondering, he didn’t, ahem, succeed with me.

Well, in the spring of my senior year, business got slow. And Yours Truly got laid off. I remember asking Bob the manager why he did that, especially after all that praise for my cleanup work, and this is what he said:

“You were non-productive.”

Yeah, Bob. You spoke more truth than you knew. You’re darn right that I didn’t, ahem, produce. Not in the way that you defined the term.

thanks kinda on the nose, isn’t it? i thought you were going to say that you did more work than everyone else but made the same wage.

this was much.. more poetic?

Thank you, horostam.

Actually, all of us worker-peons got lousy pay. And our attitudes? Equally lousy.

This, despite company-sponsored pep rallies that focused on the importance of cheerfulness. And team play. Oh, was that concept drummed into us.

The employee mix was heavy on students — from the local high schools and the nearby state college. And, if we high schoolers thought we were cynical about our jobs, well, the college kids had us beat by a mile.

Sales _are_ a measure of output.

The problem IMO is not that “output=sales”.

The problem is that once you’re there, you accepted that productivity can be measured monetarily, which has all sorts of implications. The author does touch on it earlier on, but then ignores it.

Even if you were to accept that you’d measure productivity in money terms, you still have a problem, but it’s still not sales=output.

The problem is that sales are an aggregate that is pretty much impossible to disaggregate, hence may be achieved by many many combinations of factors, which, especially for SME, will have significant variance. Yes, on average people are “equally productive”. But on average all have IQ of 100 too. Variance matters.

And I don’t buy the red graph “converted to gini”, as there’s nil methodology on how it’s converted (and, importantly, what “productivity” is author using there? The same he derides before?).

If you want to show how two distributions are different, you usually center them on their means. Moreover, I don’t buy comparing distribution of gini coefficients globally to productivity distribution. Distribution of gini coeff is not income distribution (for example, I can have the same gini coefficient with different underlying income distributions).

IMO, a way better way to attack this theory is by “assumption of change/removal”.

That is, you do two thought experiments. In the first one, you remove the person (or persons) and see what impact it has (and impact here need not be monetary! See what happens if you remove 10k police officers from their beats). For most companies over few tens of people, removal of a single person tends to have small marginal impact – with a few exceptions.

The exceptions tend to be “sales” people (or traders at banks and the like). But what gets ignored there is that when you transplant those “exceptional producers” elsewhere, all of sudden they are not so productive – unless they effectively use some sort of “capital” they built at a previous company and can use immediately.

So it’s not them per se who are super-talented and productive. In a way, taking a good salesperson from a competition is not unlike taking their business secret, but more legal. You’ve taken their investment.

Which, IMO, makes the whole “productivity” shtick dumb. Because we’re not in 15th century where there was only individual contribution (well, even then it wasn’t, but let me simplify a bit). The environment matters, and the environment is NOT a pure capital or labour thing.

I wanted to step back and let readers have fun with the post, since his conclusion is correct and his argument is clear (which does not necessarily mean well substantiated). I had HUUGE problems with that bit re the productivity of people in a narrow job category v. inequality across societies.

This comment is much better than the article itself.

Also, nobody uses sales per worker as a measure of productivity. Output =/= sales at the firm level. Heard of the term “value added”?

Thank you. It is true that we are no in the 15th century. Good riddance!

Back in college, a physics professor of mine explained the rigor of economists with the following:

Economist: There are two paths in seven dimensional space. Where they intersect….

Physicist: ?

(because there is no particular reason to believe that two paths will intersect. The assumption that the do requires at least SOME effort at proof)

BINGO! All those curves in Economics texts are nothing more than cartoons. There is no functional relationship between the ordinate and abscissa. No actual math – just hand waving.

Actually, there is lots and lots of math in economics – calculus in many cases. That is how they make it appear to be a pseudo-science instead of a religion.

The problem with economics is that it doesn’t believe in the scientific method where you develop a hypothesis, come up with the math for it, and then rigorously test it with experiments. Newton’s Laws of Physics were developed that way and stood the test of time for 300 years. Observations, especially of Mercury’s orbit, indicated there were flaws in his theory and Einstein came along to solve that. Many of Einstein’s predictions (e.g. gravitational waves) have been demonstrated in experiments but there are observations that appear to conflict with his theories, so they are looking for a new theory to extend physics into.

Einstein would be fine with that when they develop the new theory – he himself was trying to figure out the bigger picture after his general relativity theory. Nobody thought the less of Newton after Einstein’s new theories were created. Instead Newtonian physics is still used daily for most engineering applications. The more complex relativity and quantum physics are reserved for the cases where they are needed.

On the other hand, economists view it as a personal affront if their pet theories are challenged using facts (e.g. tax cuts pay for themselves). They simply declare the facts to be wrong or the theory was not executed to the fullest, which is why tax cuts keep being passed to reduce deficits even though that is repeatedly shown not to actually work.

You can’t do calculus on nominal data.

To be fair, the economists define, with some moderate rigor, the specific conditions necessary to actually render microeconomics questions solvable, such that the question becomes “given a strictly concave 7-dimensional budget surface and a strictly concave function of 7-dimensional indifference surfaces, what is the maximum valued intersection?” That they proceed to reduce this to a two-dimensional problem of choosing between a single good and everything else to reduce the math is almost gauche to point out, and you aren’t supposed to dwell on the fact that this cannot be scaled up to a macroeconomic case except in the most cartoonishly truncated examples.

And as a miraculous result of this rigor, all markets clear instantaneously across all time periods and so sales = output by virtue of the fact that prices are set to ensure that every good produced has a buyer. A complete theory of society is thus realized without resort to even a single differential equation, making the framework of economic thought more economical than a clumsy mess like Fourier’s thermal conductivity.

I didn’t read the all of the article but I think productivity is beating down labor to make them produce more units per unit time.

“When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’ ’ The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words mean so many different things.’ ’ The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master — that’s all.”

― Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

If one considers who has received the nation’s incremental wealth from the increase in the nation’s real output per hour since 1973, it is clear that labor is not ‘the master’, as wages adjusted for inflation have remained virtually stagnant since then. So who exactly has captured the wealth from all that increased “productivity”? Seems to me the GINI index cited here and other metrics such as CEO pay as a multiple of average worker pay provide clues.

Interesting piece. I have always found the concept of productivity to be almost hopelessly ambiguous. Suppose you want to measure agricultural productivity (of a worker). Some have big tractors, some little tractors, some a shovel or hoe, some a sharp stick. Some have access to fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, some have less or no access. Water resources vary, soil and topographic conditions vary. Weather varies, climate varies. At the “productive” end someone may produce a lot of crop, but are poisoning the environment, and maybe using unrenewable groundwater or unrenewable fossil fuels. The ambiguities introduced by externalities are endless. comparisons between individual workers are difficult or impossible to deconstruct from output metrics alone. And all of this is before the modeling mischief described by the author.

Sometimes enlightenment can come from intelligent comparisons. It would have been helpful to me if the author had made more of an effort to define productivity in terms he found more acceptable, so as to more effectively illustrate his point by the contrast.

Sleight of hand…

Viola!

We might want to do a monster reality regression back in time, seeing progress itself regress back to a time, I assume there was such a time, when productivity was the gain from agriculture. Plant a handful of seed and reap the bounty of a basket full of seeds. The whole idea of productivity might be a bad hangover from those first giddy days. Back then you could trade a surplus basket of wheat for a well-woven mat, later coarse cloth and the labor going into that textile became the “productivity” – no longer as passive as scattering seed and harvesting it; more time consuming, and the ball rolled on in a thousand directions, retranslating productivity into anything that produced a gain. I’m pretty sure today’s productivity produces some pretty serious losses instead of gains; losses that became gains because they could be exchanged for money. We could say today that the military industrial complex “produces” one giant godawful loss to humanity and the planet, compounding daily. But we don’t ever stop and say enough of all this. It would be a difficult exercise to actually sit down and define what the hell we mean by productivity. In the meantime, we could all admit to our confusion. That would help. And we have invented something that is very useful in spite of all the exploitation: money. Money itself can be used to simply give us all a fair share of this world. There’s no reason why not. And all the BS and rationalizing about doing your share for “productivity” can actually be ignored, except for the most important products that we need. And those can be crafted by robots and automation. The profiteers won’t like it; they’ve had a good run at the world’s expense. But they are clever souls and I have no doubt they’ll figure out a way to have more than the rest of us.

I think there is error in connecting productivity with individuals rather than connecting productivity to the Statement of Work of an Organization.

Case in point being if you replace 100 workers with Robots, and only 5 new employees are required to support the robots, the productivity per worker goes through the roof, but the reality is 95 workers lost their tasks and income entirely. Where did the productivity based savings go? Return on Investment of the organization that made the investment in robots. So capital investment displacing workers is often a primary source of productivity improvement of an organization, and therefore tying it all back to a denominator of people gives real misleading correlations and causations.

Anybody at any job can see it’s not true. But everyone pretends it is to be a “team player” on the performance reviews.

I believe that there is a relationship between income and productivity, and I think you can see it in the history of the last forty years. As Charles Murray points out in ‘Coming Apart,’ forty years ago guys who were geeky characters interested in math at your high school could maybe get a job teaching algebra after they finished college. Today, they can make over $100,000 a year working with computers virtually anywhere in America.

Besides that, the top ten percent of people on the income scale in 1980 were supervisors in factories. The technological advances in computers, digitization, et cetera, over the subsequent forty years has given them the productivity tools to leave the factory–actually the factory went overseas–and make a lot more money working for tech behemoths. So we shouldn’t be surprised that the top ten percent in income is taking a much larger portion of the national income than they were forty years ago.