Yves here. Gentrification is a tricky phenomenon, made worse by too much analysis via anecdote. More empirical work like this is badly needed.

By Kacie Dragan, PhD Candidate in Health Policy, Harvard University, Ingrid Gould Ellen, Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at NYU Wagner and Sherry Glied, Dean, Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service, New York University. Originally published at VoxEU

The pace of gentrification in US cities has accelerated, but little evidence exists on its impact on low-income children. This column uses Medicaid claims data to examine how gentrification affects children’s health and wellbeing in New York City. It finds that low-income children born in areas that gentrify are no more likely to move than those born in areas that don’t gentrify, and those that do move tend to end up living in areas of lower poverty. Moreover, gentrification does not appear to dramatically alter the health status or health-system utilisation of children by age 9–11, although children growing up in gentrifying areas show somewhat elevated levels of anxiety and depression.

People hold strong views about gentrification. Many are certain that it displaces poor families and upends their lives. Yet, while research clearly shows that gentrification is growing more prevalent, at least in the US (Couture and Handbury 2019, Baum-Snow and Hartley 2017, Ellen and Ding 2016), there has been little evidence to date on how gentrification actually affects children’s health and wellbeing. Our studies use a previously untapped data source to shed new light on these impacts in New York City, a city that has experienced dramatic gentrification in many neighbourhoods (Dragan et al. 2019a, 2019b). The existing, though sparse, research on gentrification focuses on the more limited question of whether gentrification accelerated displacement. Our studies shed light on this question too.

We rely on New York State Medicaid claims data, which cover the near universe of poor and near-poor children in New York City and allow us to track residential moves and health outcomes for a cohort of low-income children born between 2006 and 2008. Importantly, we are also able to focus on the set of children who live in market-rate rental housing and are presumably most vulnerable to displacement.

Does Gentrification Cause Displacement?

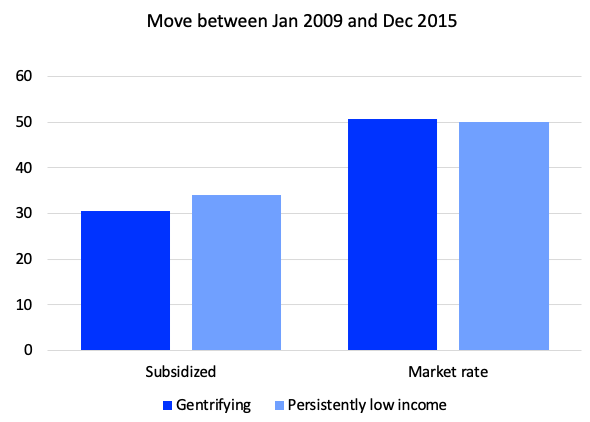

Our first study suggests that low-income children who start out in low-income neighbourhoods that later gentrify (or that experience top-decile growth in the share of college-educated residents) are no more likely to move over the seven-year follow-up period than those who start out in neighbourhoods that remain low-income and do not gentrify (Dragan et al. 2019a). While low-income children in market-rate rentals move often, they do not move any more often from gentrifying neighbourhoods (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Regression-adjusted mobility rates in rapidly gentrifying and persistently low socioeconomic status tracts

Further, we find that the average low-income child who starts out in an area that later gentrifies experiences a reduction in neighbourhood poverty. Specifically, low-income children who in 2009 live in low-income areas that later gentrify experience a roughly 3 percentage point greater decline in neighbourhood poverty than those who start out in low-income areas that do not gentrify.

While these reductions are driven by the stayers, families moving from gentrifying neighbourhoods do not end up in more disadvantaged areas than those who move from persistently low socioeconomic status neighbourhoods, though they do travel further when they move. Contrary to conventional wisdom, movers from gentrifying neighbourhoods end up in areas with similar poverty rates, and if anything, lower levels of crime. Our core results hold up to multiple measures of gentrification.

We are frequently asked why gentrification does not cause more displacement. It is possible that gentrifiers move into vacant or newly constructed homes and thus put less pressure on rents. Many neighbourhoods that gentrify start out with fairly high vacancy rates, as they have often experienced depopulation. Further, some low-income renters live in subsidised housing that is shielded from market forces, particularly in New York City where a relatively large share of the rental housing stock is regulated or subsidised. Moreover, even the private, unsubsidised housing stock within neighbourhoods may be segmented. Original low-income renters may live in buildings that are not as attractive to in-movers and thus do not experience the same increases in rent.

Perhaps most importantly, our results do not suggest that displacement doesn’t occur in gentrifying neighbourhoods; they simply suggest that rates are no higher in those neighbourhoods than in non-gentrifying ones. Low-income households tend to live in unstable housing conditions and move frequently in all types of neighbourhoods, even those showing no signs of gentrification.

Our results also do not deny the fact that neighbourhoods are changing. They are. It’s just that the changes are driven more by who moves into the neighbourhood than by who moves out.

And importantly, gentrification may affect the health and wellbeing of families and children even if they don’t experience the higher rates of displacement that many assume. Gentrification is disruptive. It brings new, often culturally different, residents to a neighbourhood; it generates changes in neighbourhood conditions that may increase the cost of living and raise rents for sitting tenants. These changes could potentially heighten anxiety and discomfort even without elevated rates of displacement.

Of course, some of the changes that gentrification brings to low-income areas might enhance health, such as increased safety, improved parks, and new businesses and economic opportunities. To the extent that they can stay in their homes and communities, low-income residents may benefit from these new investments and opportunities.

Despite these potential pathways, we know very little about how growing up in a gentrifying neighbourhood affects children’s health. To help fill this gap, our second paper uses New York State Medicaid claims data to examine health outcomes (Dragan et al. 2019b). Specifically, we again track a cohort of low-income children born in the period 2006–2008 through ages 9–11. We compare health outcomes of those who started off in areas that then gentrified between 2009 and 2015 with similar children who started off in observationally equivalent low-income neighbourhoods that saw little economic change in subsequent years.

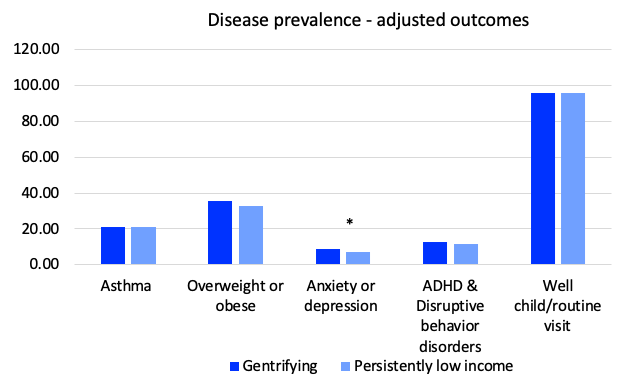

We see no evidence that gentrification affects their health-system utilisation or rates of asthma or obesity when they are assessed at ages 9–11 (Figure 2). Gentrification is, however, associated with moderate increases in diagnoses of anxiety or depression, at least among those living in market-rate housing. Anxiety and depression are rare diagnoses among children 9–11, so these increases, from very low baseline levels, are small in absolute terms. Yet they merit continued investigation as this cohort continues to age into later adolescence, when these conditions generally become more prevalent.

Figure 2 Percent of children diagnosed with selected diseases and receiving well-child visits among children ages 9–11 in 2015–17, by baseline neighbourhood

Concluding Remarks

In summary, our papers show that gentrification does not appear to bring the extreme changes that either critics or defenders of the phenomenon assume. Our research provides new evidence that, at least in New York City, children growing up in gentrifying neighbourhoods are no more likely to leave their neighbourhoods and when they move, they do not end up in more disadvantaged areas. On net, children born into gentrifying areas end up living in lower-poverty areas on average. Further, we see little evidence that gentrification dramatically alters the health status or health-system utilisation of children by age 9–11.

Still, gentrification can bring unwelcome changes too. It may raise living costs for many original residents and make them feel like they no longer belong. This may explain the somewhat elevated levels of anxiety and depression we find for children growing up in gentrifying areas. But the effects of gentrification appear to be far more nuanced than typically believed.

From a policy perspective, our research shows that low-income families living in subsidised housing are more likely than their peers in market-rate housing to remain in gentrifying neighbourhoods as they change and less likely to experience elevated rates of anxiety and depression as they live through those changes. Our research also suggests the potential value of efforts in gentrifying neighbourhoods to ensure that all residents feel part of the community and can take advantage of any new opportunities.

See original post for references

Thanks for this. It is indeed a very complicated subject, and one in which so much ‘evidence’ seems framed through peoples ideologies. Its a matter of personal interest as just last week my slightly grotty neighbourhood was listed in the top 50 neighbourhoods in the world by Time Out (I’ve no idea who voted for this).

All urban areas change and adapt over time and much of this process is self-balancing – run down areas attracting investment as cheap building stock becomes available – ‘hot’ areas, choking themselves off as prices drive people away.

I think a key variable is land ownership – as always. When people are on short term rents, they are very easy to drive out when an area gentrifies. On the other hand, people and businesses who own their own properties, or have secure tenure, can benefit enormously in many ways. This is I think a key reason why gentrification is rarely such a hot topic in most continental European cities where the process is slowed down by stricter rental laws. There is mostly just a matter of people complaining about tourists and hipsters. There are surely worse things to be worried about.

Gentrifying (upscaling) and slumming are processes that exist on a continuum. Studies like this to me miss the mark by using select data to look backward.* The negative effects with gentrification are not expressed well along a timeline of a decade (a generation of kids); they are found in the forward, future landscapes that are produced, and these effects seem to me pretty clear. Whatever it does for those specific kids on that cohort study, we do know that gentrification will effect their future-chances to move into that same gentrified neighborhood.

Gentrification is about future displacement. In urban areas, these displacements have names (slums), and we are starting to re-adjust our geographies of them, from the inner-city to those aging suburbs which have begun to experience limited access to investment, transportation, social services, and public representation.

*I am always skeptical of data that define when and where gentrification starts and occurs. Gentrification as a process runs along streets, skips blocks, picks up other places. Neil Smith described it as frontier forts that cluster together. Even data that is scaled to a census tract block won’t really capture it. So who knows where those kids on that study timeline fit, and how it skewed the percentages of comparing them as a block against those who left.

Gentrification is about future displacement

This, exactly. As someone who is in affordable housing, this is the argument from the advocates and the communities affected by gentrification.

Gentrification is sometimes less of a worry than disinvestment, but it is still very real, and its effects are felt way into the future.

And this study dealt with New York City. NYC ain’t, say, St. Paul or Minneapolis, MN where gentrification as a subject is whispered. One has to look the history of a city as to how, e.g., law enforcement, schools, rent history, absentee landlords have handled changing neighborhoods. Looking at gentrification in New York is almost anecdotal.

Gentrifying areas are usually poorer neighborhoods and poor neighborhoods are usually poor (lacking) in park sites. While new neighborhood development (gentrifying developers) are charged fees for the municipal “recreation fund”, often those fees are spent elsewhere (not in the neighborhood).

Gentrification is a tricky issue. There is currently a 500+, market-rate, high-density housing development proposed for a poor (black) area of LA. Many of the concerns depicted in the article are playing out there, today. LA is already “park poor”, so the legacy residents will likely have to hope for local economic opportunity from any new development.

PS. For non-white residents increased “safety” usually means more police patrol, which means more fear for them.

Part of this may be that low income residents may be willing to put up with additional rent costs in return for the conditions of a gentrified neighborhood. If QOL life goes up and you can take the hit to your wallet, then you accept that tradeoff. There also may be an improvement to social standing; the gentrifying transplants often will have a social respect for the “natives,” as they have established status and more community knowledge. In hipster terms, they were there before it was cool.

I think there’s less to be drawn on with the medicaid data as NYC has a relatively robust health care safety net for youth as compared to the nation as a whole. I’d be more interested to see similar data for gentrified neighborhoods in, say, Austin or the Denver metro area.

Amen on health care and Austin – very different from New York.

Low income non-gentrifying neighborhoods tend to have low diversity. Gentrification can also be called diversification. Thought we had stopped arguing a long time ago that diversity was good. Those who dont want gentrification have a single race agenda imho.

It sounds like the instability driven by being poor and moving frequently ANYWAY swamps the effects of gentrification.

The last time I was in London visiting an artist friend in the East End after a gap of about 5 years. I could hardly recognise the place. Much of that which my late East Ender wife gave me a tour of around 30 years ago has long gone. Some of it was pretty seedy but for me it had much more character than what has replaced it, but I suppose that especially the pubs & clubs have lost their use as the majority of East Enders have left for Essex.

My old mate has also since left due to being priced out as have a few other artistic characters some of whom I knew briefly – one in particular who had a great little 2nd hand bookshop whose fading memory now hangs over a car park. Musicians it seems have joined the exodus due to the lack of the kind of bars where they could play & the same thing has led to film workers I know personally moving out from other areas in London, despite the rates they earn having risen 50% over the last few years in an effort to keep them close while having to pay extortionate rents.

This article I read some time ago sums it up to an extent & I agree with my friend when he described the process as akin to sterilisation resulting in a kind of neutral blandness. In terms of the US Stephen Fry stated that he missed the old edginess around Time Square, while accepting that it was at least safer.

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/28/artist-adam-dant-chronicles-london-gentrification-priced-out-shoreditch

“Musicians it seems have joined the exodus due to the lack of the kind of bars where they could play”

Same thing, the death of live music, and nightlife around it, is happening in California, and I suspect nationwide. The reason here, and perhaps some UK spillover?, being that ASCAP and BMI, music licensing houses, are extorting money out of any public venue where live music is played.

They take the owners who won’t pay to federal court and they never lose.

It’s easier for business owners to just refuse their premises for live music. All that’s left is busking on the street or playing in places that pay and pay…and the composers don’t really get much out of licensed music either, the managerial and institutional music licensing bureaus keep a lot of what they collect.

They even sued bar owner who used a commercial pandora account:

“Carlos O’Charlies owner Carlos Cruz reportedly said that the bar licensed music through a Pandora business account. ASCAP is reportedly seeking between $750 and $30,000 for each of the three songs it claims, according to a complaint viewed by The Baltimore Sun.”

https://pitchfork.com/news/ascap-hit-multiple-us-bars-with-copyright-lawsuits/

I hadn’t thought about that side of it & even back in the early 80’s a West Indian I knew who owned a very popular pub in which I would feature as a DJ who never said anything eventually closed down due to receiving a gigantic bill backdated for about 6 years – it was a red hot place now also a car park in a place of a few bars of the coffee & fake plastic trees variety.

Ironically most of what I played was imported from Jamaica ” Lover’s rock ” reggae followed in the wee small hours by old jazz & blues of which many of the artists were dead or perhaps did not receive any royalties anyway. I remember that Bonnie Raitt put together a campaign quite sometime ago to redress that fact.

Thinking about future displacement as mentioned above made me think about the equivalent process that is happening in rural areas of the mountain west. I’m not sure if gentrification is the right term, since to me it implies a combination of race and class. But the “Bozmanification” of these areas does seem likely to have some of the same down range effects as ranches get subdivided into sizes to small to actually ranch and are only affordable to the wealthy.

The only empirical analyses of relevance have been narrowly focused on how rising land prices and development have affected plain-folk communities such as the Amish, and only where their presence as a tourist draw was economically important to the region.

In fairness, ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC represent musicians (or whoever holds the public performance rights to their songs) and the live licenses they sell to public venues or the fees paid to the Copyright Office for jukebox stickers are how musicians get their royalties for the songs that they have written. The link in comments that refers to the lawsuits states that ASCAP had repeatedly approached these venues and explained what the license fees are for but that the venues still refused to buy licenses and continued to illegally play copyrighted music without contributing to royalty payments. The range of fees for violations are statutory, and each of those organizations has loggers that go to unlicensed venues and record violations. The violations are per song played, so they are being kind if they limited it to three songs. They could sit there all day and record violations, and if past practices are still being followed, they generally offer to settle, but the settlement agreement will contain stiff violations for future infringements. The purpose of these lawsuits is to encourage people who are publicly playing musicians’ compositions to pay the people whose music they are playing (if things haven’t changed, the purpose of the lawsuits was more educational than punitive, settlements were generally reasonable and mainly covered the cost of the program).

They would be wise to settle, and buy the licenses if they are going to play copyrighted music. Their violations are recorded and the damages are statutory, and there really is no legal defense. They will lose on Summary Judgement if they go to court. I worked on one of these programs as a summer associate when I was in law school. Again, these organizations represent artists trying to get fairly paid for their works, so I don’t see them as the bad guys (except that many musicians, sadly, do not hold the public performance rights to their own songs). Musicians are free to write and copyright their own songs (and they should definitely try to self-publish or hold onto the public performance rights), and they will inevitably join one of these organizations if they want to receive any royalties for their work or they can play traditional music.

The unsettling whiff I get from these pronouncements is that there’s a tacit (IMO rather gaslighting) implication that the community displacement resulting from gentrification is unexpectedly benign because: [1] children are not displaced from gentrified neighborhoods any more frequently than they are from non-gentrifying ones, and; [2] that displaced children are displaced on average to areas with no-worse or better economic and quality-of-life possibilities. Suddenly, the rent control which NYC communities have had to fight for for years to protect appears, in this view, as the saving caveat which makes displacement less grossly impactful. I suspect that this view minimizes [a] the economic hardship (including impacts on small entrepreneurs) which nevertheless results from the influx of higher incomes into neighborhoods, and completely overlooks [b] the way that the political concerns of communities suffering displacement are themselves displaced by the class interests of gentrifiers and the developers, which diverge decidedly from those of the outright poor and struggling working-class communities targeted for “improvement”. Indeed as the authors state , “It’s just that the changes are driven more by who moves into the neighborhood than by who moves out.” I guess we’re supposed to breathe a sigh of relief that fast-walking hipsters and financially stoked millennials are more likely to vote for neoliberals like O’Rourke and Buttigieg than candidates of their odious counter-faction on the right. As for me and others who have been at the barricades of the struggle for affordable housing and economic justice in NYC for years, we’re waiting to exhale.